They’re merciless and extreme, but sanctions rarely work

Donald Trump’s favourite strategy for exerting pressure is economic sanctions. From their use in 1990s Iraq to Iran today, these measures punish the poor while the elite emerges unscathed, writes Patrick Cockburn

I was in a village surrounded by orange trees by the Diyala river north of Baghdad in 1998 at a time when Iraq was the target of stringent UN sanctions. Looking across a field, I saw several men running towards me, clutching something in their hands. They turned out to be local farmers, who had been told that I was a visiting foreign doctor, and wanted me to look at ageing X-rays of their children, often taken a decade earlier when an X-ray unit in a nearby town was still operating. They said that it had closed down because of a lack of spare parts some time after an embargo – amounting to a tight economic siege – was imposed on Iraq by the UN after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990.

I explained to the farmers that I was a journalist and not a doctor. They were disappointed, but they still insisted on taking me to their homes to look at their sick children. One man produced his 10-year-old daughter Fatima, a little girl in a red dress, whom he supported with his hands under her armpits. She looked cheerful and healthy enough, but when he took his hands away her legs instantly gave way and she crumpled in a heap on the floor.

Back in Baghdad, farmers like the ones I had met in Diyala were envied because they were getting enough to eat and earnt good money by selling fruit and vegetables in the markets. In Iraqi cities the standard of living, which had been close to that of Greece in 1990, had plunged to a level close to that of Mali. The supposed aim of sanctions was to keep money out of the hands of Saddam Hussein and stop him rebuilding his military machine after his defeat in the first Gulf war. But the UN’s own statistics showed that their greatest and most lethal impact was not on Saddam or his regime but on the very young, the very old and the very sick. The World Health Organisation concluded by 1996 that “the vast majority of the population has been on a semi-starvation diet for years”. Another UN agency estimated that between 6,000 and 7,000 children were dying every month because of sanctions. A once high-grade health system was collapsing, as a visiting foreign medical team discovered when they witnessed “a surgeon trying to operate with scissors that were too blunt to cut the patient’s skin”.

I have seen many victims of economic sanctions over the years, but for me, the misery they cause is summed up by the memory of seeing those frantic farmers in Diyala with the dusty, old but carefully preserved X-rays of their crippled children. Economic blockades, embargoes, sanctions – the term varies but the mechanism is always the same – are some of the cruellest forms of warfare, always striking at the weakest and the poorest. It is a merciless collective punishment of an entire population, whether the target is Iran and Syria today or Iraq 20 years ago.

Victims of sanctions take terrible risks to survive: in Iraqi Kurdistan a few years earlier, I was in a village called Penjwin whose inhabitants earnt just enough money to survive by defusing mines and selling the scrap of aluminium wrapped around the explosives for a small sum. Many died in the minefields, a legacy of the Iran-Iraq war, and others could be seen walking on crutches in the village after losing a foot or a leg.

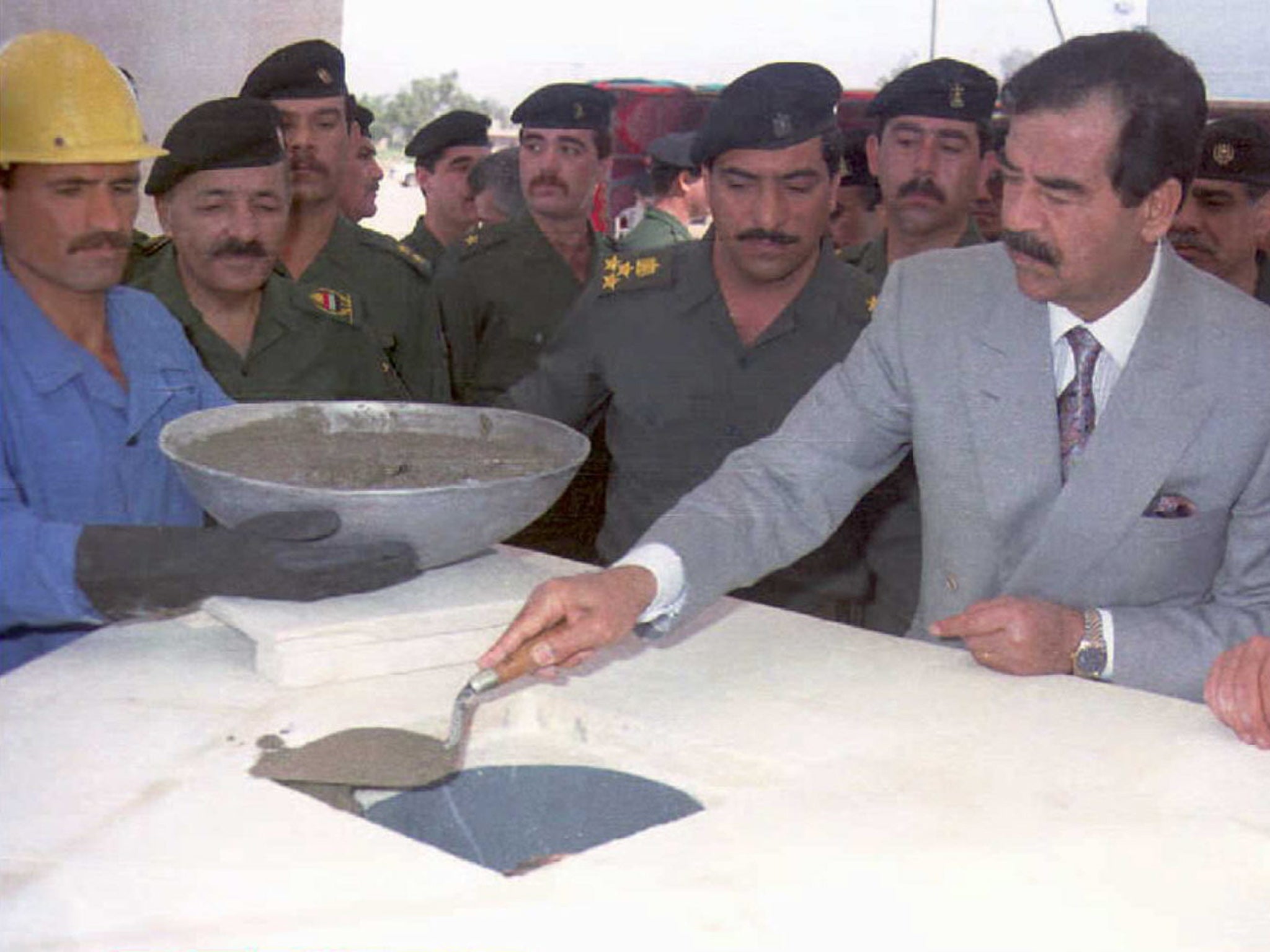

Sanctions were supposed to starve the Iraqi regime of money and resources, but the only new buildings I could see in Baghdad were giant new mosques and palaces built by Saddam Hussein for his own and his family’s greater glory. In practice, the ruling elite had been strengthened by sanctions because it could monopolise scarce resources and make huge profits on the black market (Saddam’s elder son Uday made tens of millions of dollars smuggling cigarettes into Iraq from Turkey). A diplomat in Baghdad told me that sanctions affected “the 21 million ordinary Iraqis, but not the 500,000 members of the elite”. An oil-for-food agreement in 1995, under which Iraq could export some oil, though the oil revenues were controlled by the UN, provided more funding for a toxic system but did not change it.

The supposed aim of this elaborate economic blockade, nominally run by the UN – though in practice controlled by the US and its allies – was to contain Saddam Hussein and prevent him re-arming. At other times, American officials would declare that they wanted regime change. Neither objective made much sense: the Iraqi army had, by and large, refused to fight in 1991, when it was well-equipped, and refused to do so again in 2003. Sanctions had little to do with its actions.

Western powers systematically exaggerated the military threat posed by Saddam Hussein, a classic piece of threat inflation symbolised by Iraq’s alleged – though it turned out to be non-existent – secret stockpiles of WMD.

In order to counter this supposed threat by the ramshackle Iraqi military machine, inoffensive items like lead pencils were banned because the graphite might be used to manufacture nuclear weapons. The importation of chlorine for cleaning polluted water was likewise banned because the chemical might be used for making poison gas. Ambulances could theoretically be used for transporting or treating Iraqi soldiers, so they were left without tyres, with their axles resting on concrete blocks.

I wrote many articles describing and denouncing sanctions in the 13 years between 1990 and 2003, but without any visible impact. Saddam Hussein had been so demonised, and the threat posed by him so exaggerated, that cutting off his economic supply lines appeared to many to be a sensible and necessary course of action. Critics of US and British policies were denigrated as appeasers or secret sympathisers with the Iraqi regime. Two UN humanitarian coordinators for Iraq, senior officials in charge of relief, resigned in succession in protest over the mass misery caused by sanctions, but their objections were ignored.

Nevertheless, it is worth recalling the prophetic words of Denis Halliday, one of the UN officials who resigned his job, who said before he did so in 1998 that “what should be of concern is the possibility of more fundamentalist Islamic thinking developing. It is not well understood as a spinoff of the sanctions’ regime. We are pushing people to take extreme positions.”

He was speaking years before the rise of al-Qaeda in Iraq, which later became Isis, but his warning about the unintended, but inevitable consequences of sanctions is memorable. Iraqi society was wrecked to such an extent that it has not been restored to this day and, just as Halliday had predicted, this wreckage was the seedbed in which al-Qaeda and Isis took root and flourished. A very real connection exists between what sanctions did to Iraq two decades ago and knife attacks by Islamic fanatics in central London in 2020.

Sanctions are difficult to criticise effectively because they lack the drama of war with dead or maimed bodies lying beside bomb craters. It is impossible to prove that banks are so frightened of official censure and punishment that that X-ray equipment or dialysis machines cannot be paid for by charities (as happened recently in Syria, according to a classified UN report). This deniability is one reason why sanctions are attractive to governments, as is the knowledge that their side will suffer no immediate casualties. To voters at home, squeezing hostile nations economically appears more humane than dropping bombs on them. Few noticed that, for all the suffering inflicted by Iraqi sanctions, they wholly failed to displace Saddam Hussein, who was overthrown by military action.

Sanctions and embargoes have the long-term purpose of starving out the enemy, though this is seldom starkly stated. As a leading naval power, Britain has traditionally imposed blockades on its enemies, one of the most rigorous and effective being the blockade of Germany in the First World War, which continued even after the Armistice in 1918. “Three-quarters of a million Germans died of malnutrition,” according to Lizzie Collingham in The Taste of War: World War Two and the Battle for Food.

Food shortages certainly did contribute to German demoralisation, but it was not the prime cause of their defeat. The continuation of the blockade after the shooting had stopped had another dangerous effect, as was pointed out by the British prime minister Lloyd George to fellow leaders of the Allies in 1919. He told them that “the memories of starvation might one day turn against them ... The Allies were sowing hatred for the future; they were piling up agony, not for the Germans, but for themselves.”

A century after Lloyd George made his prophetic warning, sanctions are the chief instrument of American foreign policy. In his three years in the White House, Donald Trump has started no wars, but he has repeatedly used sanctions, sometimes limited in scope, as against China, and sometimes all-embracing, as against Iran. For all his verbal bellicosity, Trump prefers the financial power of the US Treasury to the military strength of the Pentagon.

It is in his confrontation with Iran that Trump has broken new ground, often eschewing military action and relying instead on a campaign to isolate Iran economically and in every other respect. Ever since the US withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, this chokehold has been regularly tightened. When Iranian missiles struck US facilities in Iraq on 8 January after the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani, Trump did not retaliate militarily but introduced more sanctions to intensify his strategy of “maximum pressure” on Iran. This has largely shut down Iranian oil exports and is targeting financial transaction, insurance and shipping, as well as a diversity of items including carpets, gold, cars, steel, aircraft, currency, debt and industrial output.

“It is only the traffic lights in Tehran that have not been sanctioned,” says Adnan Tabatabai, speaking about the effects of sanctions at the European Council on Foreign Relations in London. US companies are banned from trading with Iran, but so too are companies from third-world countries under threat of US legal retribution. It is an impressive demonstration of US economic power: EU attempts to circumvent sanctions on Iran in order to preserve the nuclear deal have been feeble and ineffective. Governments and companies do not want to offend Washington or to be sucked into the Iran-US confrontation. Unsurprisingly, after vainly waiting for a year for a European rescue, Iran switched to a military option, launching pinprick guerrilla attacks on the US and its allies in the Middle East.

The Iranian economy has been badly hit. Its oil exports are down from 2.8 million barrels a day before sanctions to 500,000 barrels a day at the end of last year. Economic decline contributed to political unrest: a rise in fuel prices last November provoked demonstrations in which at least 300 people were killed by the Iranian security forces. Further protests erupted when the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps accidentally shot down a Ukrainian airliner. Yet Tabatabai does “not believe there is a revolutionary mood”, noting that sanctions have made Iranians more dependent on the state. The poor need free food and the better-off look to other forms of government assistance, repeating the pattern we saw in Iraq between 1990 and 2003.

A reason why the policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran adopted by the Trump administration may not succeed is that Iran is less dependent on oil revenues than Iraq. “In contrast to many other oil-exporting countries, especially in the Persian Gulf region, Iran has a rich and diverse economy,” writes Bijan Khajehpour in a study of the impact of sanctions. Energy may be the backbone of the Iranian economy, but it is not its only asset; on the other hand, the US is trying every means to seal off these other forms of trade.

Washington has made heavy-handed but impressive efforts to isolate Iran by pushing all pressure points available from oil exports to the cancellation of international football matches. Even so, the economic encirclement of Iran is much less tight than that of Iraq under sanctions. Commercial companies in Europe may be intimidated by the prospect of getting on the wrong side of the US Treasury, but they are not legally restricted from doing so.

Three significant gaps in the economic siege works erected by the US around Iran are important. China is Iran’s most important trading partner, with trade totalling $42bn (£33bn) in 2018, 55 per cent of this being earned by Iran’s exports of oil, petrochemicals and minerals. Of the countries neighbouring Iran, the most important is Iraq, which imported $12bn worth of goods from Iran last year. Iraq is sometimes called Iran’s “lung”, through which it can breathe economically and which it is impossible for the US to close down because of Iran’s strong influence in Baghdad. Iraq also gets much-needed electricity and gas from Iran. “The Iraqis can ask the Americans, ‘how do you expect us to live without electricity?’” writes David Jalilvand, a political and economic consultant on Iran.

Could sanctions ever force Iran to negotiate with the US? The Iranian supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, is unlikely to look for talks while Iran is looking weak after the assassination of Soleimani, the shooting down of the Ukrainian passenger plane and the anti-government protests. The situation would get graver for Iran if it loses its Chinese economic link or Trump is re-elected as president in November. But hawks in Iran are strengthened because they can say that Iran tried to compromise with the west between 2015 and 2018 and that did not work.

Washington is currently looking for a surrender from Iran rather than a deal, going by Trump’s summary of his objectives when announcing the latest round of sanctions. He said his aim was to stop Iran having the money to “support its nuclear programme, missile development, terrorism and terrorist proxy networks, and malign regional influence”. If these maximalist demands are taken seriously then Iran will never accept them, outside a defeat in a full-scale war.

The other US aim is regime change in Tehran, though this is denied by the White House. Hopes rise periodically in Washington that the Islamic Revolution in 1979 will be reversed by the same sort of mass protests that overthrew the shah. But any government with a monopoly of armed force, and the willingness to use it, is next to impossible to dislodge, whatever its unpopularity. Sanctions make governments poorer and less able to provide for their people, but they also give them somebody else to blame.

“While there seems to be an expectation in Washington that economic pressure on the Iranian population will lead to further unrest and protests against the state,” writes Azadeh Zamirirad of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin, “research rather suggests that economic sanctions often hurt oppositional groups and have little impact on the coercive capacity of the state.” This is certainly the lesson of sanctions on Iraq, the dire effects of which are still with us. Economic warfare kills a lot of people, but it does not win decisive victories.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments