Donald Trump, his backers, and the race to protect the 2024 election

As Republicans who have embraced the former president’s false claims about the 2020 election being ‘stolen’ make their way to the midterms, Chris Stevenson asks what it means for the contest in 2024

If you need an illustration of the long-lasting political effects of the riot at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021 – and the false claims of Donald Trump, about the legitimacy of the 2020 election, that preceded it – look no further than the fate of Liz Cheney.

The three-time congresswoman from Wyoming, the least populous state in America and one of its most staunchly Republican, was crushed in the party’s primary by a challenger endorsed by the former president. Harriet Hageman, who is now expected to be the state’s lone representative in the lower chamber of Congress during the national midterm elections in November, has echoed Trump’s claims about widespread voter fraud in 2020.

Cheney, who won 73 per cent of the vote the last time the primary was run two years ago, is the daughter of Dick Cheney, the former vice-president. Cheney herself has said that she would likely have been locked in to return to Congress if she had fallen in line with Trump’s fanciful version of events. “The path was clear. But it would’ve required that I go along with President Trump’s lie about the 2020 election. It would’ve required that I enable his ongoing efforts to unravel our democratic system and attack the foundations of our republic. That was a path I could not and would not take,” Cheney said during her concession speech.

Instead she became the face of the congressional hearings into the events of 6 January, as the vice-chair of the House of Representatives select committee. “Tonight, I say this to my Republican colleagues who are defending the indefensible,” she said during the first 6 January hearing, which was aired on primetime television in early June. “There will come a day when Donald Trump is gone, but your dishonour will remain.” Those hearings would continue throughout the summer – and Cheney’s House ambitions would be gone before the end of August. But she is now the person that the “never Trump” movement can coalesce around.

Cheney was not the only one to lose out in the wake of the 6 January hearings. In late June, the Republican speaker of the Arizona State House, Rusty Bowers, told the committee that he knew Trump and those around him were seeking to pursue an effort to have him invalidate the 2020 election in his state, which had seen a narrow win for Joe Biden. “It is a tenet of my faith that the constitution is divinely inspired, that this is my most basic foundational belief,” Bowers, a Mormon, said. “And so for me to do that, because somebody just asked me to, is foreign to my very being; I will not do it.” Bowers had voted for Trump in the 2020 election.

Earlier this month, Bowers would lose his own primary to a Trump-backed candidate, David Farnsworth, who has supported Trump’s falsehoods that the 2020 election was stolen. That was after Bowers was officially censured by Arizona’s Republican Party for “having demonstrated he is unfit to serve the platform of the Republican Party of Arizona and the will of the voter of the Republican Party in Arizona”. In a highly unusual intervention in a contested primary, local party officials called on voters “to expel him permanently from office”.

On the same day of the hearings on which Bowers spoke, Georgia election worker Shaye Moss testified that, after she was singled out by Trump and his allies as part of their baseless claims, her life was thrown into chaos.

“It’s turned my life upside down. I no longer give out my business card. I don’t transfer calls. I don’t want anyone knowing my name,” she told the committee. “I don’t go anywhere with my mom. I don’t go to the grocery store at all. I haven’t been anywhere at all. I’ve gained about 60lbs.

“I don’t do nothing anymore. I don’t want to go anywhere. I second-guess everything I do. It’s affected my life in a major way. In every way. All because of lies,” Moss said, fighting back tears during her testimony.

Tonight, I say this to my Republican colleagues who are defending the indefensible: there will come a day when Donald Trump is gone, but your dishonour will remain

As primary season continues, a recent analysis by The Washington Post found that, in the 41 states that have held nominating contests this year for positions – either state or national – that involve an office with some form of power over elections, more than half of the Republican winners so far – about 250 candidates in 469 contests – have, at least in part, embraced Trump’s false claims about the 2020 presidential election. If this analysis is reduced to the six battlegrounds that ultimately decided that election – Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, all of whose results were subject to fierce denouncement by Trump – at least 54 winners out of 87 contests (that is, more than 62 per cent of nominees) have supported Trump’s falsehoods.

In the words of The Washington Post: “The count covers offices with direct supervision over election certification, such as secretaries of state, as well as the US House and Senate, which have the power to finalise – or contest – the electoral college count every four years. Lieutenant governors and attorneys general are also included, with each playing a role in shaping election law, investigating alleged fraud or filing lawsuits to influence electoral outcomes.”

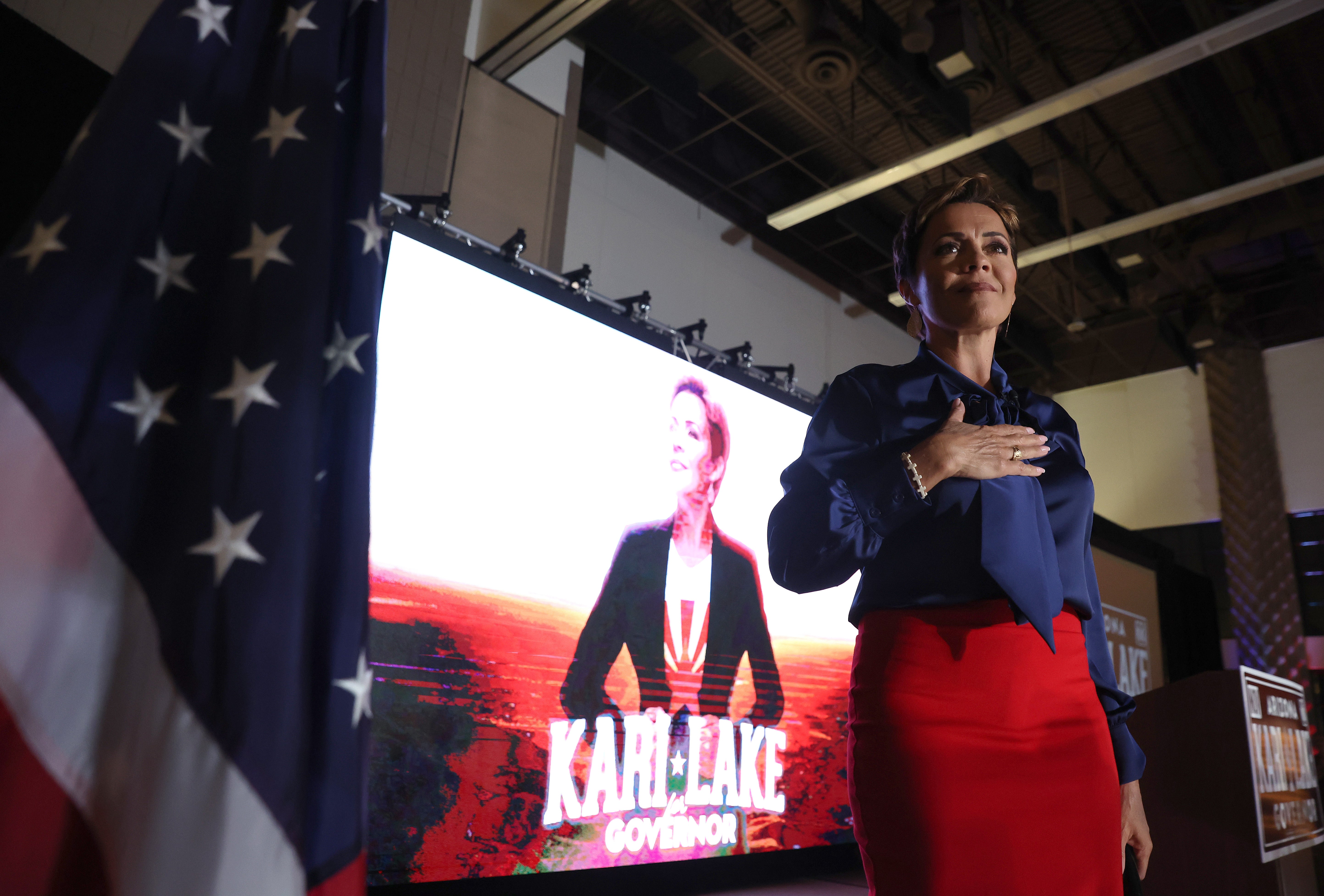

For example, earlier this month in Arizona, Republicans nominated Kari Lake for governor and Mark Finchem for secretary of state. Both candidates have backed Trump’s false claim that the 2020 election was stolen. Finchem had previously introduced several resolutions, in his role as a state legislator, that sought to decertify the results of the 2020 election in three major Arizona counties.

While not all of those who make it through the primaries will win against their Democratic rivals in the midterm elections in November, the pattern will certainly raise concerns about how to ensure the integrity of the presidential election in 2024. Another indication of the direction in which the Republican Party is moving comes from the 10 Republicans in the House of Representatives who voted to impeach Trump over his conduct in relation to the events of 6 January. Four opted to retire instead of potentially losing to Trump-backed rivals in the Republican primaries. Of the remaining six, Cheney was the fourth to be defeated in those party primaries – leaving just two still in contention ahead of the elections in November.

Beyond the issue of candidates, a recent study by three election reform groups suggested that 13 states have already approved laws that could help to facilitate more partisan control of election administration – or strengthen the potential for changes to individual election processes to be made – with another 229 bills still pending in 33 states.

If this is the lie of the land, then what is to be done? In July, a bipartisan group of 16 US senators banded together to introduce legislation to reform the 1887 Electoral Count Act. This statute, which many in Congress agree is outdated, created the process that governs how states transmit their results in a presidential election to Congress – and then how Congress counts these votes and declares a winner. It is also the act that allowed space for Trump to try to disavow the results of the 2020 presidential election.

The current law says that only one member of the House and one member of the Senate are needed to challenge any state’s set of electors. The new act – the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022 – would increase this, so that one-fifth of the members of each of the two chambers of Congress would be required.

The new bill would also bring in measures “aimed at ensuring that Congress can identify a single, conclusive slate of electors from each state”. This follows the testimony given by Bowers, during the 6 January committee hearings, that it was suggested that he send an alternative slate of Republican electors to Congress as part of the larger effort to overturn the 2020 election results. The new bill would also create a judicial process with expedited review – first by a three-judge panel, then by the US Supreme Court – over certain matters related to disputed electors.

Lastly, the proposed act, which would require 60 votes to pass the Senate, would also reaffirm that the “constitutional role of the vice-president, as the presiding officer of the joint meeting of Congress, is solely ministerial”. This follows the question that arose in 2020 of whether Mike Pence could refuse to certify the election result.

A second proposed law, the Enhanced Election Security and Protection Act, would then increase criminal penalties against those convicted of intimidating or threatening candidates, voters or poll workers, and would also legislate for better preservation of election records.

The proposals were put together following months of meetings, but there is no guarantee that they will make it through Congress – although the leading Republican in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, has left the door open at least a crack when it comes to the narrower concept of electoral count reform (as opposed to the kind of wider voting reform that the Democrats and the White House are pushing for). McConnell has called the proposals around the 1887 law “worth discussing”.

As for Liz Cheney? She is apparently planning to launch a political movement – suggested names include “The Great Task” – with the primary aim of preventing Trump from winning the White House back in 2024. Trump has yet to announce that he is definitely running in two years’ time – although he has strongly hinted at it.

“I’m going to make sure people all around this country understand the stakes of what we’re facing, [and] understand the extent to which we’ve now got one majority political party – my party – which has really become a cult of personality,” Cheney – who it is speculated could be considering a run at the White House herself – told NBC in recent days.

Whatever form this political movement takes, it is clear that it is something we will certainly hear plenty about in the long run-up to the 2024 presidential election.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

43Comments