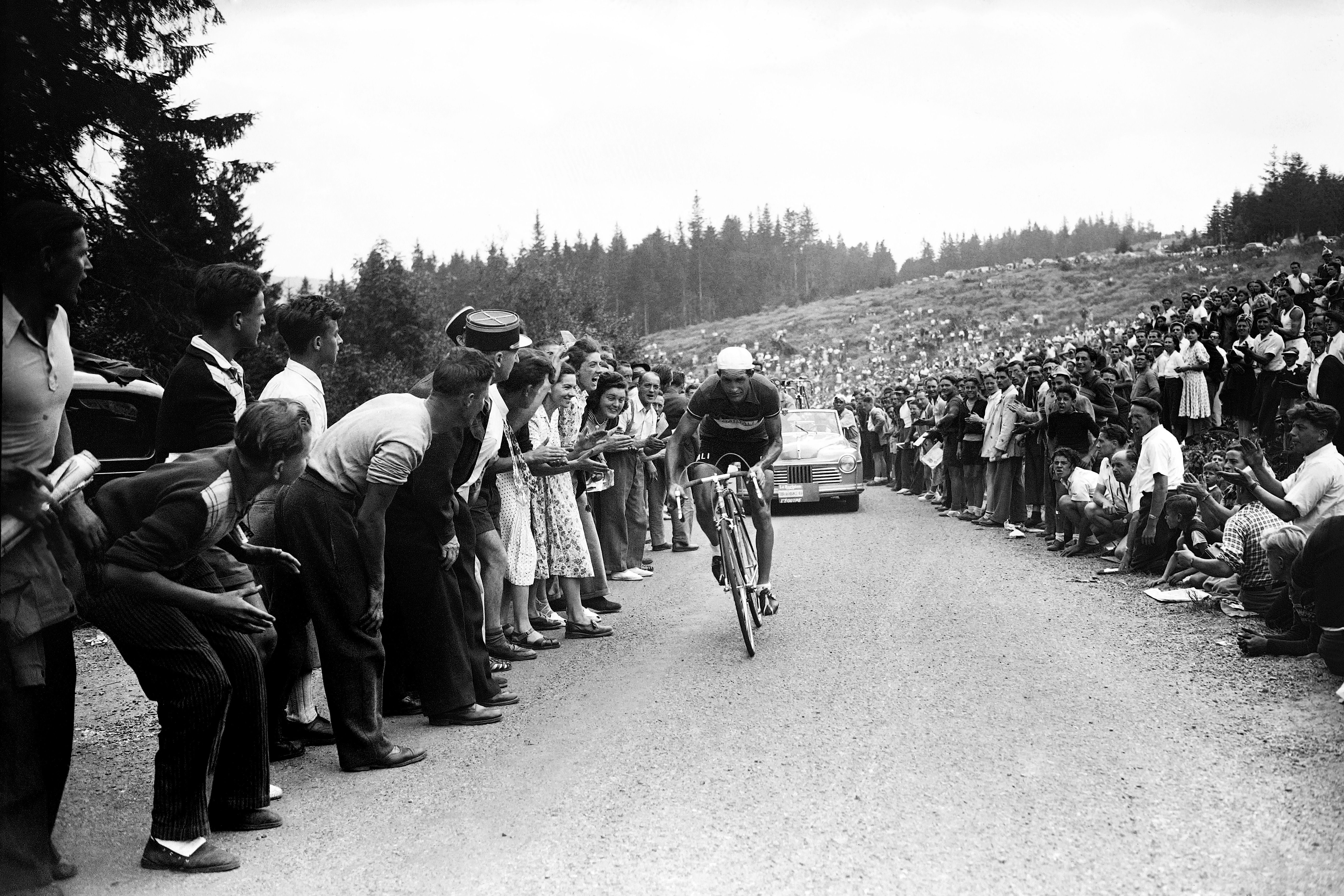

The big business of the Tour de France

The jewel in cycling’s crown is owned by one family with a long history. Here, in the prologue to his new book, Alex Duff explores an episode from 2011 about an attempt to take the sport in a new direction

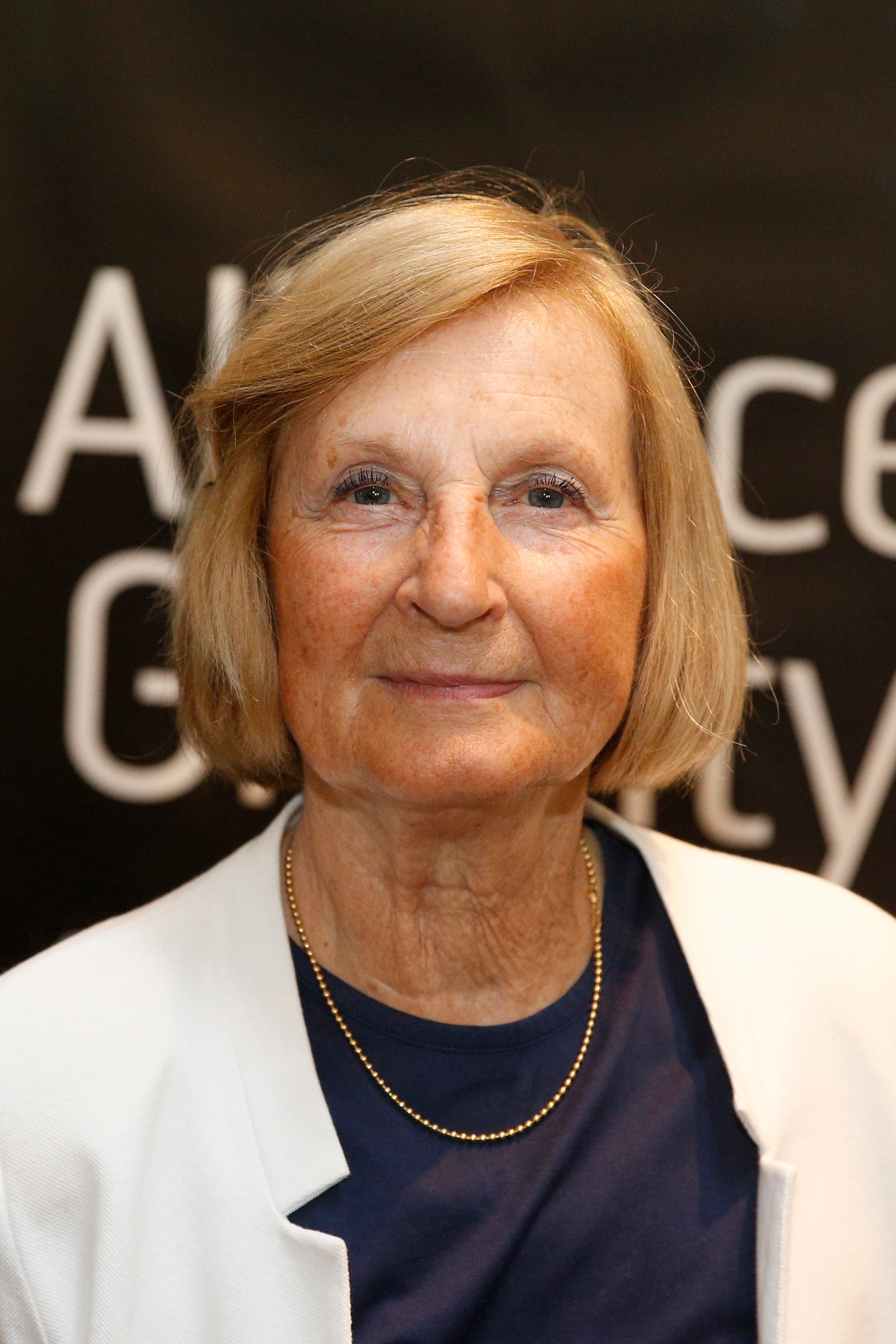

Marie-Odile Amaury occasionally came across them at private functions. With her unassuming manner and simple but stylish clothes, she chatted amiably about the weather, house prices and holiday destinations. Peering out from under her blonde fringe, and fixing the middle-aged men from Belgium, Italy, Spain, the UK and the United States with her piercing blue eyes, she was always polite and spoke respectable English to those with no French. The owner of the Tour de France kept her public profile so low that many of them did not recognise her.

While drinking tea out of china cups on the balcony of the Belgian king’s residence outside Brussels on the eve of a recent Tour de France start, she was chatting with one of them about their grand surroundings for several minutes. They joked about their holiday homes, how theirs also had similar decor, marble columns and chandeliers, and a garden with its own golf course. The man thought the unassuming lady he was talking to was an aide to the Belgian royal family, or perhaps a member of its catering staff. It was only when she introduced herself that he realised he was chatting to a woman who was richer than their host, King Philippe.

Those of the Tour de France team managers who recognised Marie-Odile Amaury would often try to steer the conversation to the business of cycling. Face to face with the matriarch who controlled the purse strings, they reminded her they received a mere €51,234 in compensation to attend the Tour de France, with a few free hotel rooms thrown in. The money barely covered their expenses for petrol for the team buses and cars during the three-week race. Under Madame Amaury’s feudal system, the teams could use the profile of her race to reap their own income from private sponsorship deals, but they did not have the right to share in any of the television and race sponsorship money which was said to approach $100m a year. This was a highly unusual situation in modern-day sport, and made the team managers bristle when they met her in person.

Their complaints would turn the air cold within seconds. At first, Madame Amaury would, with a thin smile, refer them to her senior executives for further discussion. But if they persisted with their gripes, she could turn prickly. Striding up to her purposefully, one of them exchanged a kiss on each cheek in line with French custom before he asked her abruptly if he could iron out some differences, face to face, right away. Hardly skipping a beat, she said, “Happy New Year...” (it was mid-July) and walked past him.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, two-thirds of French listed companies remained partly family-owned, according to the economist Thomas Philippon. That compared to fewer than one-quarter of those in the US and UK. The fortunes of the very wealthiest of these French dynasties from the Bettencourt family, custodian of L’Oréal, to the Arnaults, owners of Louis Vuitton, are picked over by the media.

Leaders of most family-owned companies tend to be more risk-averse. They are more conscious of threats that may weaken their “heirloom” as they endeavour to pass it on carefully to the next generation. Among them, Marie-Odile Amaury. She and her family owed their wealth from the Tour de France to a media empire started in 1944. In this historical context, the cycling team managers who confronted her were not just coming up against the iron will of a proud pensioner, but against what they felt was the immovable force of the French way of doing things. Sometimes, they felt all the energy they used up to achieve change in the sport was like trying to run through a brick wall.

But one day at the start of 2011, a plot was hatched. A dozen of them filed into the hall of a grand building in the City of London to discuss how to bring down cycling’s antiquated business model. Rothschild & Co, around the corner from the Bank of England, was so embedded in the financial district of London that it owned St Swithin’s Lane, the narrow street where it was located. It was on this same site in 1814 that the Duke of Wellington had hired the founder of this family dynasty to finance Britain’s flagging war effort against France. By obtaining large amounts of gold through its network of couriers, dealers, brokers and bankers, the bank said it provided the financial firepower to rescue British troops from “almost certain defeat” against Napoleon.

In the City of London, the group of cycling team managers were told that, if push came to shove, they could pull off the same kind of coup against Madame Amaury

The Rothschild & Co office today looks more like a museum than a banking institution; it has oil paintings on the walls, a library and an unusual ornament – a 1960s safe with four billion different combinations. In one room, until recently, five pasty-faced bankers from gold trading houses in the financial district fixed the price of gold at 10.30am each day. In a century-old ritual, each would raise a mini Union Jack flag on their desk when they agreed with the day’s opening price. All this history and tradition was a bit of a surprise for the cycling team managers who were used to meeting in French no-frills chain hotels with little more luxury than free wifi and a buffet breakfast. They were more familiar with the workings of bicycle components than high finance. As they took in their surroundings, they were curious as to what would come next. A couple of days earlier, they had received by email a 12-page prospectus outlining the business plan for a new championship – World Series Cycling.

In a wood-panelled room, Jonathan Price, the Englishman chairing the meeting, sported curly dark hair tinged with grey and swept back off his forehead, and an expanding middle-aged girth straining against his pressed shirt. In his forties, he was pale with brown eyes, and wore the top two shirt buttons undone; he could have passed for a middle-aged pop impresario. He spoke slowly because there was a lot to take in; he explained who he was and went through the details of the prospectus. In truth, like most British people, he knew almost nothing about professional cycling. He was a football man.

A decade earlier, he was one of the young executives who had turned Manchester United into a commercial superpower after its listing on the London Stock Exchange. Price’s job had been to replace provincial advertisers like the local travel agencies and car dealerships with global brands at Old Trafford stadium. Now, he told the group of men staring at him, there was a tremendous opportunity to modernise cycling.

Incorporating the Tour de France and other major races, Price said World Series Cycling would also include events on the east and west coasts of the United States, and in Asia. And the best news of all, the teams would get 64 per cent of the equity. Currently, their equity stood at zero. To pull off this exciting new championship, all the teams would need to be united. Until everyone was on board, this project had to stay under wraps. There was no question of going to Madame Amaury to ask her to surrender her family’s position. “Pepsi would not go to Coca-Cola to tell them their plans,” Price would say to one confidant.

Sitting alongside Price was an Asian man with a well-kept beard. Majid Ishaq, head of Rothschild & Co’s Consumer, Retail and Leisure department. A Manchester United season ticket holder, five years earlier he had brokered the Glazer family takeover of the club he supported. At the time, Rothschild became a target for fan activists outraged at the Americans loading the club with debt. At one point, they shut down its computer network and broke into its offices. Ishaq coolly underwrote the deal for 45 minutes when, because of a clerical error, the family’s funds did not come through on time. The Glazers were so impressed they offered him the job as United chief executive.

Ishaq had drawn up the World Series Cycling financial model. If he helped get the project over the line, Rothschild & Co would get a cut of the income. Using the bank’s maths models, he predicted the series would have an annual pre-tax profit of €39m by its fourth year. That would give the teams €25m to share between them, and that was just the start; the revenue would continue to rise exponentially if the series was able to market itself effectively as a brand like, say, the Uefa Champions League. Cycling was, of course, nowhere near as popular as the $1bn football tournament, but there was still a lot of untapped potential.

As the gaggle of team managers prepared to leave the City of London for the airport, they took one last look at their noble surroundings. The bottom line, they knew – World Series Cycling would need to include the Tour de France to be successful. Price could organise as many startup races as he wanted, but the French race brought in up to 80 per cent of the teams’ media exposure during the nine-month cycling season. That exposure was worth tens of millions of euros in publicity for their sponsors such as American tech company Garmin, Spanish phone company Movistar and Belgian floor maker Quick-Step. Most team bosses desperately needed to be at the Tour de France start line to get these big sponsorship deals. And they knew that Madame Amaury, who would not even entertain them for a chat unless it was about the weather, would not agree to dilute her family’s patrimony.

That would be like Napoleon surrendering to the Duke of Wellington.

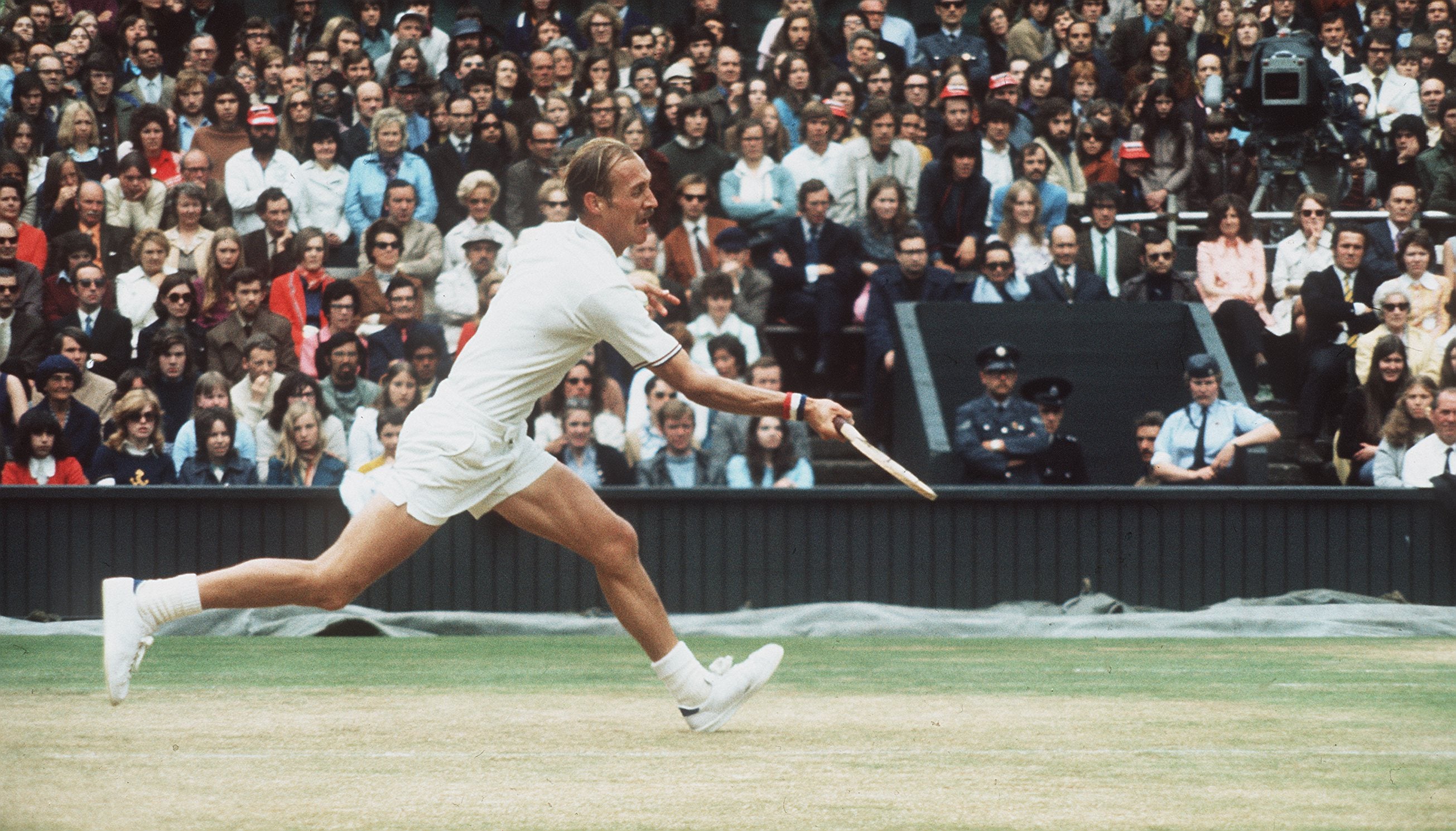

Price had an answer to this conundrum. In 1973, he explained, leading tennis players had transformed the sport, wresting control from organisers of the Wimbledon championship. The grass-court tournament was the tennis equivalent of the Tour de France, the standout event in what, at the time, was a fragmented circuit of year-round events. Based at an ivy-walled clubhouse with 18 lawn tennis courts in a London suburb, the championship was managed by the All-England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, an invitation-only members club that considered itself the guardian of the game. Etiquette maintained men had to bow and women curtsy when there was a member of the UK royal family in attendance. Occasionally, Queen Elizabeth II would make an appearance. Among the house rules were players who had to wear white, with no sponsor logos.

The man in charge of compliance at Wimbledon was a former army captain called Captain Gibson, the tournament umpire. In the summer of 1972, he had marched on to the Centre Court in his dark woollen suit and ordered a 24-year-old Californian player to go to the locker room and change her dress because it contained the purple logo of a sponsor, a cigarette maker. The following year, the Wimbledon committee banned a gangly six-footer from Yugoslavia after he skipped a Davis Cup match for his country to earn a bigger cheque in a new event in Montreal.

Fed up with being pushed around like this, the Association of Tennis Professionals, a newly formed player group led by Americans with little respect for tradition, announced a stunning move – a Wimbledon boycott. Defending champion Stan Smith was among 80 players to pull out. Instead of stars like John Newcombe and Rod Laver, journeymen that few people had ever heard of filled the men’s draw. A little-known Czech, who admitted he didn’t much like playing on grass, won the title. Within weeks, the boycott had paid off. Tennis authorities granted players the right to play wherever they wanted. It was a pivotal moment, moving power into the hands of the athletes, and paved the way for broadcast and sponsorship revenue, much of which flowed down to them in prize money.

In the City of London, the group of cycling team managers were told that, if push came to shove, they could pull off the same kind of coup against Madame Amaury. It would undercut the business empire that her father-in-law had launched more than six decades earlier during the Second World War with a helping hand from the gentlemen around the corner at the Bank of England.

Extracted from ‘Le Fric: Family, Power and Money: the Business of the Tour de France’ by Alex Duff, out now (£22, Constable)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments