Eating disorders: ‘We have created a society of people who are unable to eat normally’

It’s never just about weight. Obesity and anorexia both signify underlying mental health problems. The NHS has just published new guidelines on treating eating disorders but they are meaningless without the funding, explains Lorna Collins

The UK is facing a double-barrelled health crisis. It manifests itself through weight and food, but conceals a much darker, underlying problem. Six per cent of adults have a so-called “eating disorder” (such as anorexia or bulimia). At the other end of the spectrum, 29 per cent of adults and 20 per cent of children are obese. But whether you’re about to die from malnutrition or morbid obesity, whether you’re at one end of the scale (and, indeed, scales) or the other, you are suffering from a form of disordered or anomic eating.

Adrian Brown is a specialist dietician and a research fellow at the Centre for Obesity Research, University College London. Brown helps patients who are obese and overweight make lifestyle changes to manage their body weight. This is called “body weight regulation”. Brown says 11 per cent of adolescents have “a clinically significant eating disorder”, whilst 40 per cent of UK teenage girls meet the criteria for “disordered eating”; they may not have a full-blown eating disorder, per se, but their relationship with food, weight and their bodies is difficult and dysfunctional.

All these statistics present a growing population of young people who use food (bingeing, restricting, purging) to express something about themselves. These behaviours with food are influenced or caused by a number of underlying different factors (psychological, social, familial, environmental, genetic, predisposition and more). Food becomes an exercise in distraction, eclipsing whatever is causing disordered behaviour. The consequent loss or gain of weight is a visible expression of deeper issues.

For example, I developed anorexia after I had a very serious brain injury (after being thrown by a horse), which led me to have total amnesia. I could not control anything about my life; I could not remember who anyone was, I did not know who “Lorna” was. This took nearly two decades to resolve. Despite the angst, I discovered that I could control something: the food I ate. The more I thought about food, the less I had to worry about what on earth was going on with my identity. Finding ways to restrict, to eat less every day, overtook all concerns. Anorexia became my identity. It was a relief, a distraction, something I could be “good” at.

Anorexia and obesity might seem opposites, but they exist on the same spectrum. Both are highly complex, long-standing and chronic relapsing diseases.

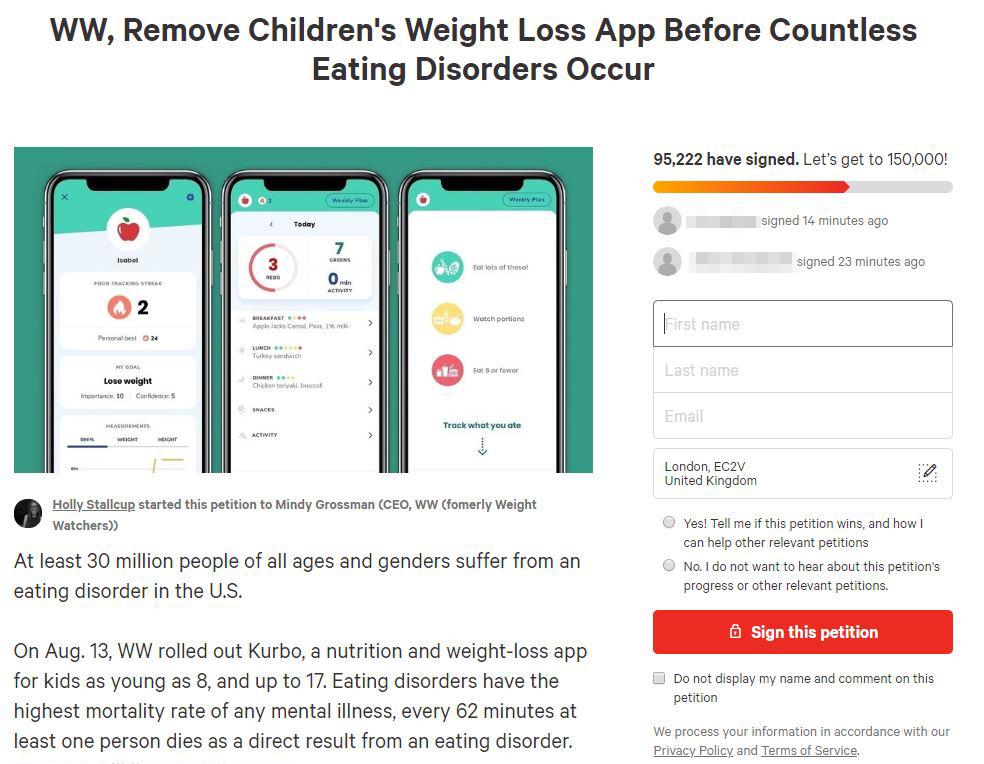

Currently, there is uproar over a new weight-loss app for children, created by the organisation formerly known as Weight Watchers (now called WW, or WellnessWins). This app was made to target childhood obesity but critics are arguing that it will directly cause children to develop eating disorders. The app is designed to help children as young as eight lose weight. Framed with an easy to use “Traffic light system” (green foods are good, red foods are bad), WW says children can use the Kurbo app “to make healthier food choices and build healthy habits, day by day”.

Dieting as a teenager triggered a 14-year battle with anorexia, and led to a number of physical and mental health issues for me. I set up the petition because I don’t want this to happen to other children

This has, understandably, provoked strong opinions from people in the press and on social media. Nearly 100,000 people have rapidly signed a number of petitions calling for Kurbo to be taken down. Rachel Egan created one of these petitions because, she says: “Dieting as a teenager triggered a 14-year battle with anorexia, and led to a number of physical and mental health issues for me. I set up the petition because I don’t want this to happen to other children. Dieting is one of the biggest predictors of eating disorder behaviours and is seriously dangerous for young people.”

But as the BBC presenter Victoria Derbyshire puts it: “A record number of children are obese in UK. If this app is not a solution, then what is?” Adrian Brown says this is a “highly complex and very difficult” question, because “there are a lack of effective services in the UK to address the increased prevalence of childhood obesity.” Not enough money exists in public healthcare, to pay for treatment programmes and help people with eating disorders on both ends of the spectrum. Brown says the app “might fill a gap”, and be used in place of a healthcare service that does not exist.

But it needs to be done with the support of a team of trained healthcare professionals. We don’t know what the qualifications of the “trainers” on Kurbo are. Brown wonders: “Does the app rely on AI technology to monitor risky behaviours?” Presumably not, but WW is not answering their critics.

Suggesting there is a continuum between obesity and eating disorders is controversial. It is hard to find any sort of dialogue between obesity and eating disorder experts. I asked mental health campaigner Hope Virgo, who is recovering from an eating disorder herself, whether the prevalent eating disorder crisis and the equally prevalent obesity crisis have the same underlying problem. Hope says: “They are not the same, but what we have created is a society of people who are unable to eat. A society where only a very small number of people can actually listen to their bodies. We need to be looking at the mental state of individuals but also pushing back on society on what messages they are preaching about being a certain size or shape.”

In other words, we have anxiety about eating. There is no “normal” any more. The norm is only a mathematical illusion. Who can help a whole “society of people who are unable to eat”? I turn to eating disorder services, which I know very well from my own experiences of being detained for many years, and eventually cured.

We have anxiety about eating. There is no ‘normal’ any more. The norm is only a mathematical illusion. Who can help a whole society of people who are unable to eat normally?

The NHS has just published new “guidelines” for commissioners and providers – the hospital and medical team who give care, and the people who direct funds (from the Home Office), to pay for this care. These guidelines seem to outline and open up new forms of care, and its access, to expand treatment for people suffering from all eating disorders – anorexia, bulimia or binge-eating disorder. Other disorders – “Osfed” (“Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder”), orthorexia, diabulimia (etc) would seem to fit in the “co-morbidities” section of the guidelines. The aim is to show how people can receive better care in inpatient, day patient and community settings.

These new commissioners are trying to make eating disorder services easier and quicker to access, with an “optimal model of service delivery”. The core aim is to initiate and deliver timely, effective, evidence-based treatment that meets the individual needs of every person with an eating disorder. In practical terms, the intention is to reduce the treatment waiting time standard (within one week for urgent cases and four weeks for non-urgent cases).

But these are just words. I’m not sure what it means, nor how it might be put into practice, given a society of people who cannot eat. I ask Agnes Ayton, a clinical lead, and chair of the Eating Disorder Faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatry, what practical difference these new guidelines will make for eating disorder treatment and recovery.

Ayton is initially positive about these guidelines, saying they could be very helpful, if implemented. Their publication is “the result of people fighting tooth and nail for adult eating disorder services”. But how might the guidelines jump off the page and, rather than just being words in print, make a positive, practical difference in treatment programmes?

Ayton says that it’s down to resources and capacity. The guidelines say that patients should be able to self-refer and be treated straight away, so a patient can just ring up and ask for help. I ask Ayton if, following these guidelines, anyone can call up her ward and ask to be admitted. She says: “We need additional staff to meet that need. This concerns the coordination of care, training and supervision. More staff need to be trained and employed to meet the need. There is a funding implication.”

I ask how sufficient funds can be obtained, to create the kind of healthcare theorised by the guidelines. (Funding comes from the Department of Health NHS England and/or the clinical commissioning groups). Individual trusts apply to either or both of these sources to gain money to pay for services. Ayton says “NHSE is hoping that we will close beds and recycle money into outpatient services. It can’t be either/or, it needs to be all levels – intensive outpatient, daycare, inpatient. People should be allowed to move seamlessly between these different but connected levels of care. For this we need extra money.”

The total costs for eating disorder treatment to the NHS are between £3.9bn and £4.6bn (plus a further £1.1bn of private treatment costs), with a consequent lost income to the economy of between £6.8bn and £8bn. In 2014, the government announced an additional £30m funding a year to support the development of dedicated community eating disorder services across England. In 2019-20, this has been increased to £41m, with a further boost committed from 2020-21 over the course of the NHS Long Term Plan.

But whether and how this money has been delivered, and effectively used, remains to be seen. The government is keen to demonstrate its funding of “severe mental illnesses”, such as schizophrenia or bipolar, which counts for 1 per cent of the population. But eating disorders, which count for 6 per cent of the population, are not considered in the “severe” category, and so do not gain funding. With this in mind, clinical commissioning groups and NHS England could increase funding for mental health, but not specifically eating disorders.

We need additional staff to meet that need. This concerns the coordination of care, training and supervision. More staff need to be trained and employed to meet the need. There is a funding implication

James Downs is a member of the Expert Reference Group for adult eating disorders at the Royal College of Psychiatry, and part of the team which put together these guidelines. Downs’s role is to represent “lived experience”, as someone who is in recovery from an eating disorder. Downs says the guidelines are progressive and positive when they “shift the emphasis on eating disorders from a narrow, BMI-focused idea of what constitutes a “real” eating disorder (ie worthy of intervention and help)”.

Great ideas, but what will ensure their practice? “I am really worried that the new guidelines will not make a meaningful difference if there is no difference in resourcing,” says Downs. “The guidelines do not represent something that can be implemented with a shifting-around of current resources. They expand on what is currently available and currently resourced, and as such need to be matched with extra funding. So, it could come to nothing.”

We come back to the sticking point: there is not enough money to pay for services that can help people overcome their eating disorders. Meanwhile, we are left with “a society of people who are unable to eat”. What do we do about that?

It’s never just about weight. Behaviours with food can point towards an underlying mental health problem, which needs to be dealt with, if individuals are ever going to live in a healthy, happy way.

Hope Virgo’s excellent, potent and inclusive “#dumpthescales” campaign aims to remove the focus on weight, and instead “encourages frontline staff to look at the mental health of a person. For some people their weight will change for no real reason but for others it will be because something else isn’t quite right and we need to be able to spot that. It is important that we get in there before people hit crisis. The longer we leave it with eating disorders the harder recovery is.”

Whichever way you look, there is a huge deficit. Guidelines are published for eating disorder treatment, without sufficient funding to initiate any productive changes. An app is made, which seems to offer a “do-it-yourself” guide to help children lose weight. This is extremely problematic. We are left with anomic eating, in its different expressions. The causes need to be addressed for any kind of healing and regulation to be obtained.

This problem reveals something about the society and culture we live in, where people express their troubles by developing disordered eating behaviours, and where it is so difficult to get help. The problem is exacerbated by the lack of funding for appropriate healthcare services. We rely on the NHS to solve everything, but it can’t.

I saw seven fellow-patients die during my time at one eating disorder unit. Those are the deaths I know of. No doubt more slipped through the net, or will. The severe risk of dying from an eating disorder has almost become a ‘norm’.

This fact is as shocking as it is terrifying and impenetrable. What will it take to accommodate a whole “society that cannot eat”? There is a finite amount of treatment available for society’s inherent (and growing) disorders. It took me 17 caustic years of suffering from anorexia, before I was eventually admitted to “Cotswold House” specialist eating disorder unit, in Oxford.

Here I finally learned how to take care of myself, and be well. Agnes Ayton leads the “New Care Model” at this unit, which provided solutions and eased my suffering. This is only one example of successful treatment, but it shows that – despite what seems a dire situation, through thick and thin – it is always possible to recover.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments