What really happened during the Great Escape?

We all know the plot to ‘The Great Escape’ but the real-life events were even more dramatic, writes James Rampton

No British bank holiday is complete without two things: rain and a screening of The Great Escape. It is one of the best loved films of all time. Which child – or indeed adult – has not dreamt of being even one-thousandth as cool as Steve McQueen is in that film? However, an engrossing new documentary titled Escaping Hitler reveals that the true story of what happened in the Nazi POW camp Stalag Luft III during the Second World War was, if anything, even more dramatic than the 1963 movie.

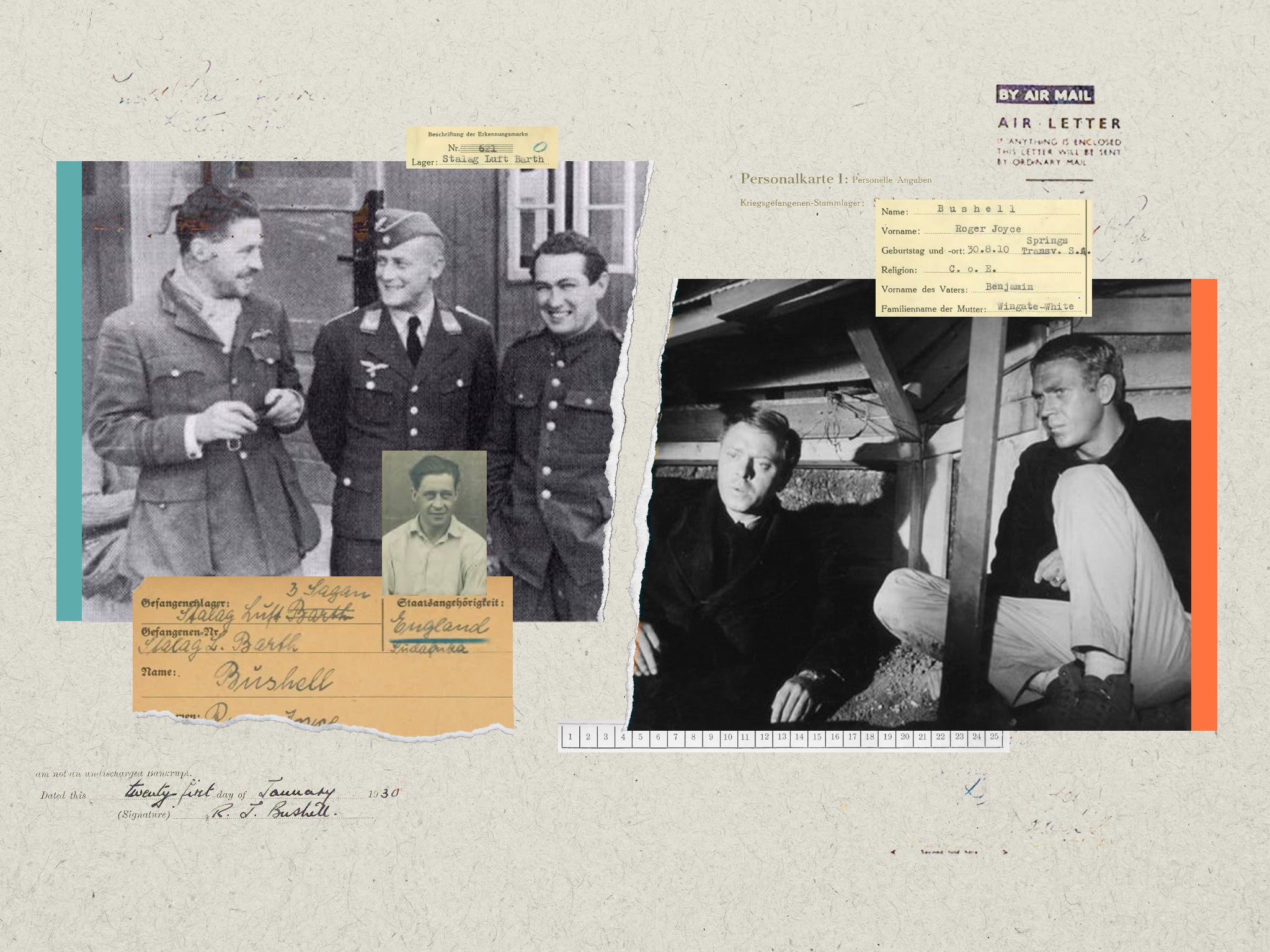

The documentary, which is showing on Sky History as part of the ongoing series Great Escapes with Morgan Freeman, makes several startling new revelations about the incident. It underscores that The Great Escape is a striking example of fact outstripping fiction. The mastermind of the actual Great Escape was a quite remarkable character: 33-year-old RAF squadron leader Roger Bushell (called Bartlett in the movie and played by Richard Attenborough). Bushell crash-landed his Spitfire in France on the day of Dunkirk and was captured by the Germans. But no prison could hold him. He and a Czech colleague escaped while being transported on a train and were hidden by a Czech family.

But after the 1942 assassination in Czechoslovakia of the leading Nazi Reinhard Heydrich, one of the main architects of The Final Solution, Bushell and his Czech comrade were swept up in a German crackdown in that country. After they were apprehended, the entire Czech family that had sheltered Bushell and his friend were summarily executed by the Germans.

Big mistake. That moment lit a burning flame within Bushell; he was absolutely hell-bent on doing his bit to defeat the Nazis. As Professor Jonathan Vance, author of The True Story of The Great Escape: Stalag Luft III: March 1944, puts it: “When Bushell learned this, he was not only outraged, but almost broken. It sharpened his hatred of Nazis which became almost pathological. It made him almost obsessively determined to do whatever he could to undermine, disrupt, disturb the Nazi regime.”

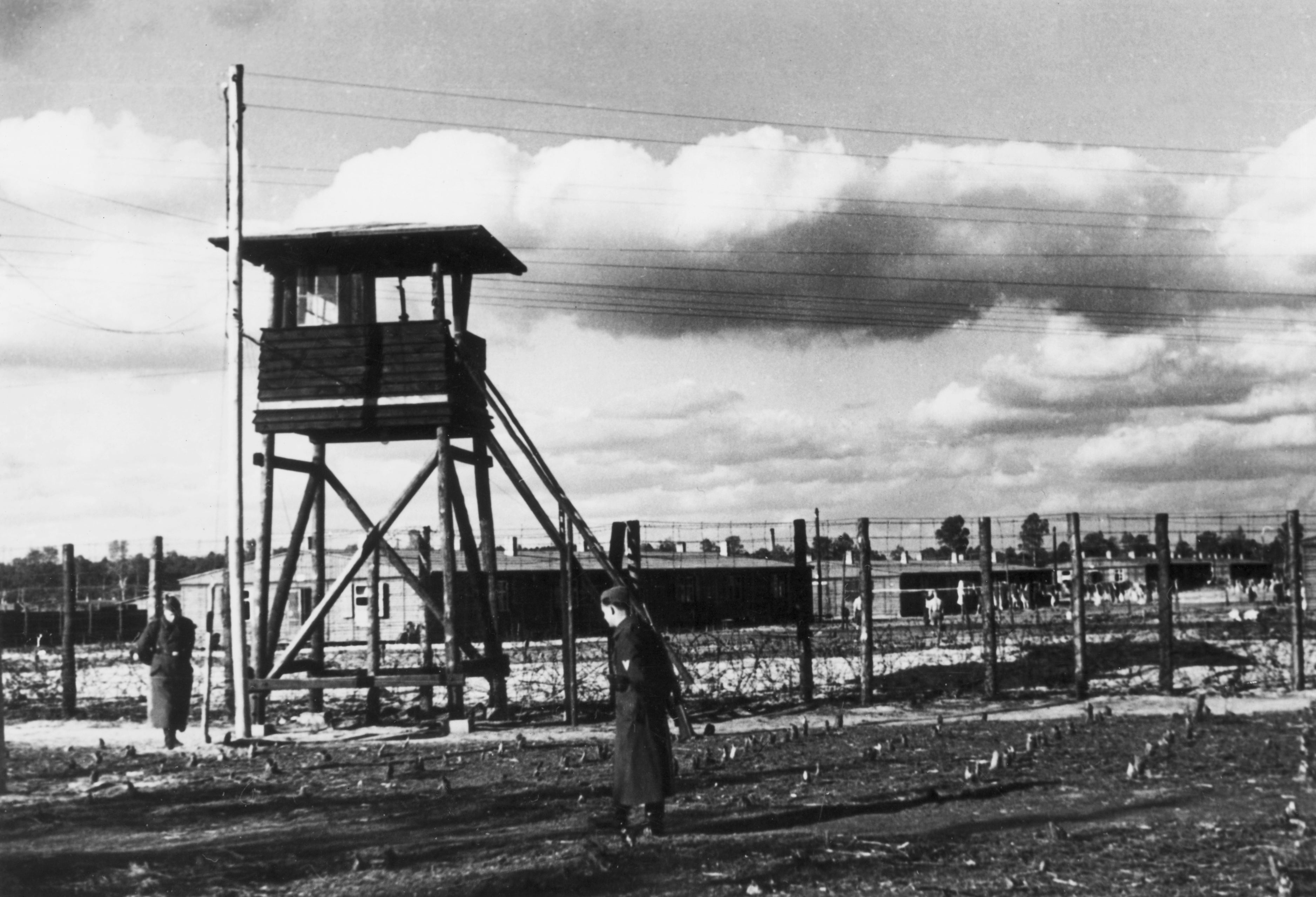

Because he had proved such a supreme irritant to the Nazis, Bushell was sent to the one place they thought could hold him: Stalag Luft III, the most notorious German POW camp. Housing only prisoners who had previously broken out of other camps, it was supposedly “escape proof”.

Bushell was having none of that, though. It was the duty of every Allied officer to attempt to escape, and he was quickly appointed “Big X”, the leader of the camp’s escape committee, known as the “X Organisation”.

Bushell believed that an escape of 200 or 250 airmen would create such chaos for the Nazi regime that it would do incalculable damage to the German leadership

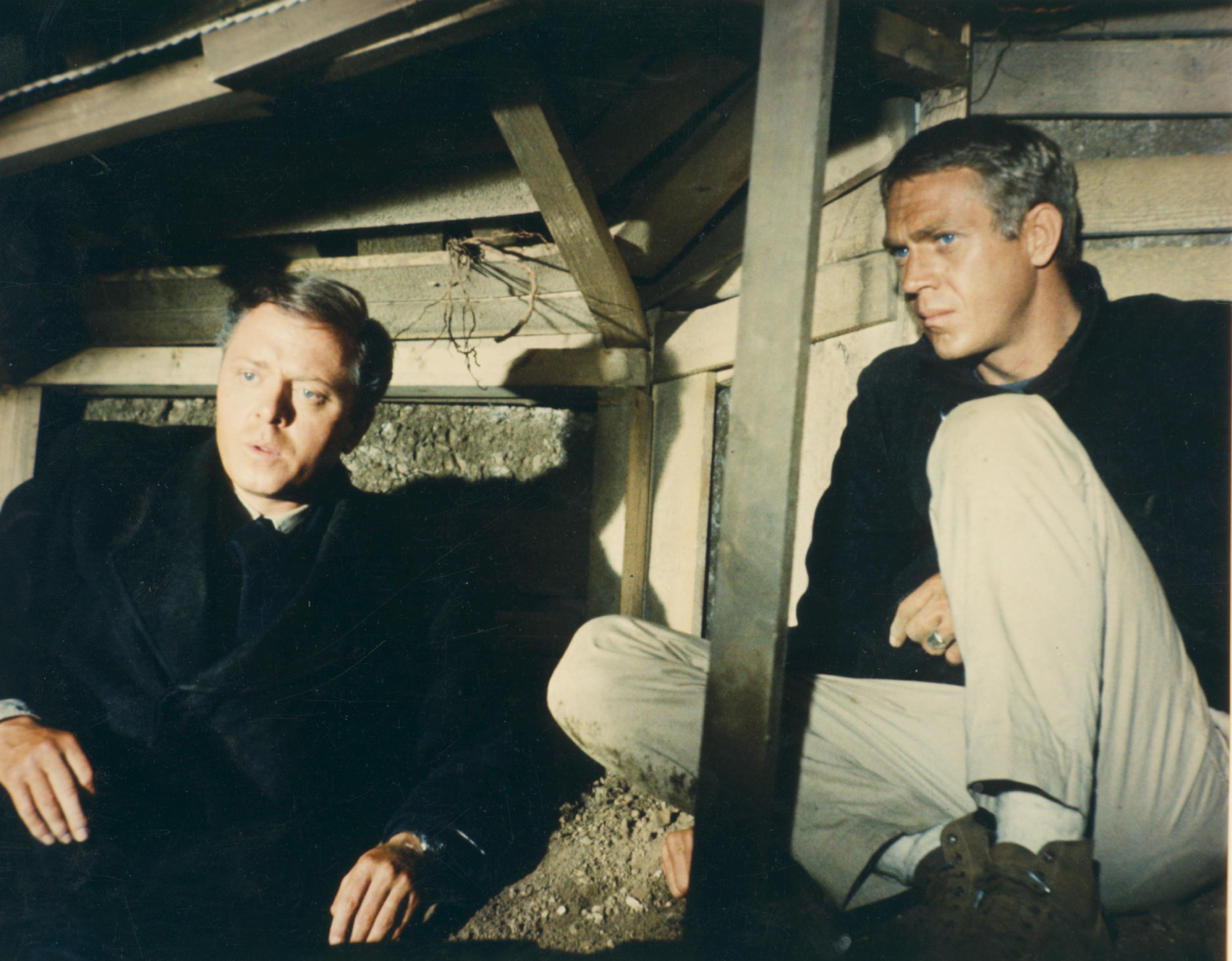

He faced severe obstacles. Stalag Luft III, near the town of Sagan, which is now in Poland, was crawling with Nazi spies. The barracks were built on stilts, making it very hard to hide any tunnel entrance.

The whole camp was constructed on several metres of fine sand, rendering any potential tunnels unstable. The sand was a light golden colour, which meant it was extremely tough to conceal once dug up. The Germans had even buried seismograph microphones underground to listen for any sounds of tunnelling. If prisoners tried to escape above ground, they had to contend with a warning tripwire, two barbed wire fences and watchtowers manned by armed guards 24 hours a day. Anyone attempting to scale the fence would be shot on sight.

But none of those obstacles daunted Bushell. He conceived an audacious plan, involving 600 inmates, to dig three escape tunnels. The idea was that if the Germans ever discovered one of the tunnels, it was very unlikely that they would ever imagine that two other tunnels were being built at the same time. The tunnels had to be 30 feet deep and more than 300 feet long in order to reach the relative safety of the thick forest surrounding Stalag Luft III. They were given the names of “Tom”, “Dick” and “Harry” to ensure their secrecy.

Peter Doyle, who is professor of history at London South Bank University and an expert on the Great Escape, says: “They wanted to make sure prisoners didn’t go, ‘how’s the tunnel going?’ Instead, they might say, ‘how’s Tom today?’”

Bushell’s aim was to liberate 250 prisoners. In so doing, he intended to divert enemy resources away from the frontline, destabilise the German army and turn the tide of the war against the Nazis.

According to Vance, who teaches military history at Western University in Canada: “Bushell believed that an escape of 200 or 250 airmen would create such chaos for the Nazi regime that it would do incalculable damage to the German leadership.”

Doyle, who has written several books on military history, observes that “Bushell’s plan was to create a massive nuisance and to lock down the Third Reich. As the escaped men spread out, like tendrils from this location right in the middle of the Reich, the Germans would have to send out all of their police and armed forces to scour the landscape. He had a mission to take it out on the German Reich for what had happened to him. And of course, these prisoners were still at war. This was an act of war against the Nazi regime.”

For all the excellent intentions of the plan, Bushell was well aware that persuading 250 airmen to risk their lives by escaping from the camp would be a very difficult task. So he gathered his men in a hut and delivered a rousing speech.

“Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time,” Bushell declared. “By rights, we should all be dead. The only reason God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug. One will succeed.” This stirring oratory was quite enough to win over any waverers.

“Escaping Hitler” makes many fascinating disclosures about this daring jailbreak. For instance, it outlines the astonishing attention to detail that went into the escape.

Doyle takes up the story. “I was involved in an excavation of the tunnel Dick at Stalag Luft III in 2003, and we made many extraordinary finds. We discovered the slab covering the entrance to the tunnel. Underneath that we found a stamp with the Wehrmacht eagle, which had been made by the prisoners out of the rubber heels of their boots.

“One of the things that is really interesting is how the secret British organisation MI9 sent materials to the camp to allow them to do this. They would send seemingly innocent objects – a gramophone, for instance. The Germans did not realise that you could turn the metal spring of a gramophone into a saw.”

The inmates were also able to utilise the food tins dispatched to them by the Red Cross to manufacture a makeshift air-line to ventilate the tunnels. They pumped air into the line using an ingenious contraption fashioned out of kit bags and hockey sticks.

The airmen employed 4,000 bed boards to prop up the tunnels. When the Nazis became suspicious about the number of missing bed boards, the POWs explained that as they had not been given enough firewood for the cold weather, they had had to resort to burning bed boards.

The list of objects the prisoners deployed in the construction of the tunnels almost defies belief: 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 20-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 1,370 beading battens, 1219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 1,000 feet of electric wire, 600 feet of rope, 3,424 towels, 1,700 blankets and more than 1,400 cans. In addition, they used pine sap from the surrounding trees as glue.

By the time the tunnel was discovered by guards at 4.45am, 76 men had escaped, and immediately began fanning out across Occupied Europe

“All these little things made really significant contributions to the Great Escape,” says Doyle. “The very mundanity of these objects shows you how the prisoners brought their ingenuity to bear.”

The captives used so-called “Stooges” to warn each other about approaching guards and outwit the network of Nazi “Ferrets” dedicated to foiling escape plans by using secret gestures akin to the tic-tac hand movements practised by bookmakers at racecourses.

The POWs also surreptitiously released the 125 tons of golden sand dug from the tunnels out of pouches secreted in their trousers during specially staged rugby matches and gardening sessions. It is reckoned that the entire process required more than 25,000 sand dumps. The men disposing of the sand had to walk in an awkward manner and became known as “Penguins”. After the escape, the Germans were shocked by the magnitude of what had occurred under their very noses.

The prisoners managed to blackmail many guards into doing favours by pickpocketing their passes. If a guard was caught without his pass, he would immediately be sent to the dreaded Eastern Front. The captives also had to deal with moles put into the camp by the Nazis. Every new prisoner had to be vouched for by someone already in Stalag Luft III. The new arrivals would be asked searching questions about their purported hometown. If someone was proved to be a spy, the POWs would warn the Nazis that they knew his true identity and told them, “remove him by 6pm, or we won’t be responsible for what happens to him”. That always worked.

In August 1943, the prisoners encountered a major setback. A Ferret discovered Tom after idly tapping his stick on a concrete trapdoor which chipped. The Germans immediately blew up Tom. But the tunnel had been so well built, the captors assumed that the prisoners must have poured all their energy into that one tunnel and stopped looking for any other tunnels.

It helped that the entrances to the other two tunnels were very cleverly hidden. The opening to Dick was concealed in a drain sump in a washroom, while Harry’s entrance was covered by a stove. Bushell decided to stop digging Dick and use it as a dump for the sand, concentrating all the POWs’ efforts on Harry.

Finally, everything was ready. Maps, fake passes and uniforms had been made by the brilliantly ingenious POWs, and Harry had been completed. On the moonless night of 24 March 1944, the prisoners drew lots to decide the 200 escapees. But again, potential disaster struck, as the POWs discovered that Harry came up 10 feet short of the forest and therefore in sight of the perimeter guards.

It was decided to go ahead anyway, and at 10pm, in a brief gap between patrols, the first POWs went into the tunnel via the entrance in hut 104. However, the process proved slower than expected. One bulky POW bashed into the side of the tunnel and caused it partially to collapse. Some other prisoners experienced claustrophobia in the very narrow two-foot square underground space and panicked.

By the time the tunnel was discovered by guards at 4.45am, 76 men had escaped, and immediately began fanning out across Occupied Europe. Unfortunately, only three of those escapees eventually made it to safety. “There were two Norwegians, Jens Müller and Per Bergsland,” says Doyle, whose own father spent five years as a POW after being captured on the way to Dunkirk. “They had the right look about them and the right language skills. They managed to persuade a Swedish sea captain to take them to neutral Sweden.

“The other one to get away was a Dutchman called Bram van der Stok. He was number 18 on the list of escapees. The lower your number, the greater your chances of escaping. He had absolutely fantastic language skills and capabilities. He travelled all the way across Occupied Europe, right through Germany, Holland, France and Spain to Gibraltar, and then onto Britain. It took him three months. He displayed amazing determination, but it also showed that he was the right man for the job.”

Adolf Hitler was livid when he heard about the mass escape and personally demanded the execution of 50 men, including Bushell. This was, of course, a heinous war crime, in stark contravention of the Geneva Convention. Doyle points out another revelation made in the documentary. “Gestapo officers took the prisoners out in ones and twos to remote locations and shot them in the back of the head.

“There was one particular officer who was so clinical that he said to his girlfriend, ‘I’m going to be late for dinner. Can you keep it warm for me?’ Then he went out, murdered two prisoners and calmly came home for dinner. That level of cold-blooded murder is shocking.”

Urns holding the ashes of the 50 murdered airmen were taken back to Stalag Luft III, where the prisoners built a memorial marking their deaths. After the war, some of the perpetrators of the 50 murders were tried in Nuremberg, and several Gestapo officers were executed. Doyle had the privilege of meeting some of the former prisoners involved in the Great Escape at his excavation of the camp in 2003. For example, he encountered squadron leader Jimmy James, who was one of the 23 brought back to Stalag Luft III after being recaptured. “He was a delight. His first response when he saw Dick was to say in a very British way, ‘oh, I say.’

Thousands of troops, police and even Hitler Youth members had to be called away from the war effort to frantically search for the escapees

“The pride that these men still had was very much present. When we took them to the site, it was a validation. It was if they were saying, ‘see this, we were here, we did this’. You couldn’t help but be moved by it.”

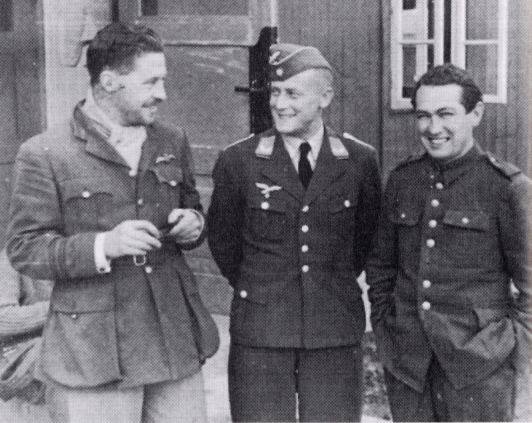

But that doesn’t mean the former POWs were boastful about their contribution. When pressed about his own achievements, James said, “we weren’t heroes, you know”. What a brilliantly British reaction! Doyle reveals that the movie of the Great Escape, which is based on a 1950 non-fiction book by Paul Brickhill, is very largely an accurate account of the breakout. It only veers from what actually happened near the end.

“Clearly, the film is a star vehicle for Steve McQueen, and so you have to have a motorbike scene.” The climactic moment where his character Captain Virgil Hilts (aka “The Cooler King”) attempts to vault the barbed wire fence on his motorbike is an iconic sequence in movie history. “It’s a fantastic piece of cinema, but it has nothing whatsoever to do with reality!”

All the same, Doyle only has praise for the movie. “Any escape is always a triumph over adversity. But this is an innately fascinating story because you have such levels of ingenuity. These were ordinary men pitted against a powerful regime who achieved something extraordinary. “The film is phenomenal. It’s burnt into our consciousness. Whenever it’s on, I always watch it. It is epic in scale, but despite that it has tremendous individual stories and shows how each one of those individuals worked in perfect harmony to create those tunnels.”

Although only three men ultimately got away, the Great Escape still caused mayhem among the German ranks. Thousands of troops, police and even Hitler Youth members had to be called away from the war effort to frantically search for the escapees.

So should Bushell’s master plan ultimately be deemed a success? “Bushell’s stated aim was to mess up the German system,” Doyle muses. “As the escapees spread outwards, they committed huge numbers of Nazis to searching for them. Therefore they did pin down the Germans and diverted their attention away from other aspects of the war.

“Bushell enraged Hitler and Goering. He sent a shockwave through the German establishment and showed they weren’t necessarily as invincible as they thought. So he achieved what he set out to do. The question is whether the loss of life was worth that.”

Vance harbours no doubts about how effective Bushell’s plan was. “Bushell’s goal was to disrupt the German High Command by flooding escapees throughout Occupied Europe. In this, I think he succeeded more than he could have ever imagined.

“News of the escape came at the daily conference at Hitler’s headquarters, and you see from this point the growing dissent in the highest ranks of the Nazi regime. You can find Germans who would be moved into opposition to Hitler because they were disturbed by what went on in the aftermath of the escape from Stalag Luft III.”

By ordering the illegal execution of 50 POWs, Hitler opened up a rift within the Nazi armed forces that would never heal. It may even have helped to shorten the war, which was Bushell’s ultimate objective. How should we remember Bushell, then? “He was, of course, a hero,” Doyle asserts. “As with all heroes, he had flaws. But like Shackleton, whose ship Endurance has just been found, Bushell was an incredible leader of men. As Big X, he was able to mobilise his colleagues and get all of those fertile minds working together. He created something which has a truly enduring quality.

“He has to be admired. He was completely on the right side of history. He was taking the fight to an obviously evil state.”

A pause. “Above all, Roger Bushell showed an unquenchable desire not to be beaten by the Nazi regime.”

‘Escaping Hitler’ is showing on Sky History at 11pm on Sunday 27 March as part of the ongoing series ‘Great Escapes with Morgan Freeman’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks