‘The house was clinging for breath’: What it’s like to live in a Tudor home as a guardian

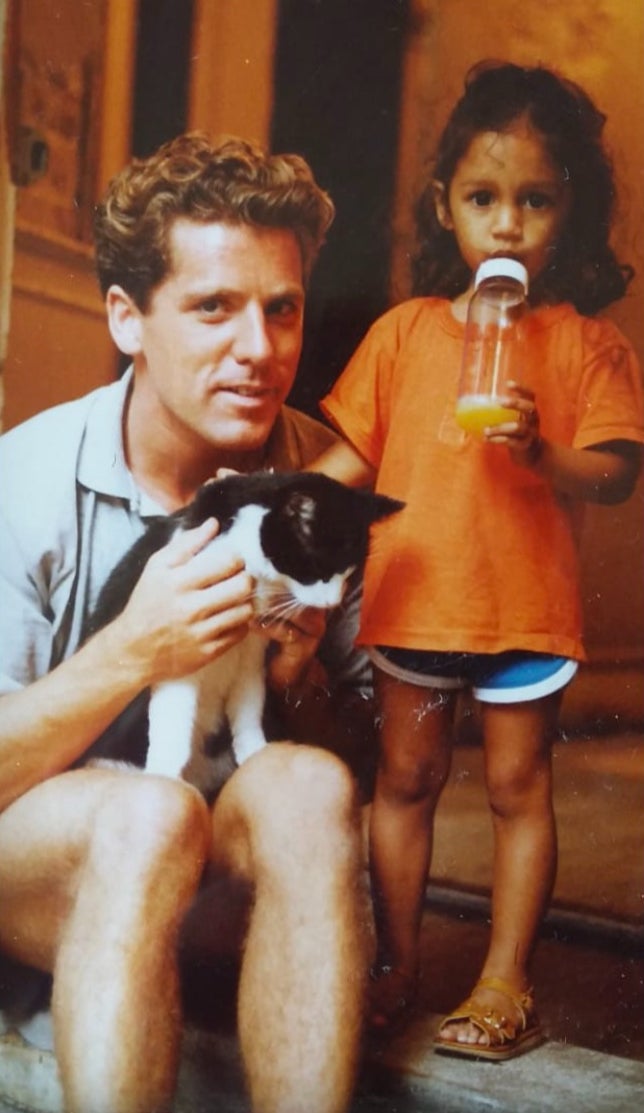

In the late Eighties and early Nineties, Julian Machin lived in London’s magnificent Sutton House as a property guardian. Here he reflects on his time there as he returns for a reunion with those he lived with

Just before moving into the National Trust’s Sutton House, I wrote in my journal:

It was going to be an adventure. I climbed one staircase, moved across, descended another and was lost inside, not knowing which direction I was facing… the dim-lit emptiness lent tranquillity with dignity – a quality existing in places where the crowd has departed. In time, all of the boarded-up windows were freed and the light flowed through the house once again.

The sinuously gracious, east-end, brick-built Tudor property on Homerton High Street has stood since 1519, and, by the summer of 1992, I’d been living there with up to four friends since 1988 while the Trust worked out a feasibility study on its future.

For the Trust, our being there ticked a box marked “occupied”, offering them security and us twentysomethings free rent. Our group – Kate, Judy, Mike, Richard and me – was altogether different from the squatters whose previous tenure had caused much pain to terminate.

It was the squatters, however, whose time has been etched into the recent history of Sutton House far more than our own. They’d left under considerable opposition and with damage in their wake. Thieves then stole some of the building’s linenfold panelling and so, for its protection, the rest was put into storage – leaving much brick, dust and decay.

On 6 January 1989 I wrote: “The atmosphere in the empty rooms told of latent personalities, but eloquent and full of significance. The state of neglect was alleviated by the miracle of the courtyard. Beneath its two-sided cloister, some soft pale greenery struggling valiantly from a patch in the middle made it like an outdoor room to which the house was clinging for breath. The courtyard made possible what – as a would-be home – seemed unlikely, because it registered as a living thing.”

By most standards, it’s a very large house and when we moved in during 1989, it took a lot of dusting, scrubbing and damping down yet never seemed clean.

The kitchen had a country table made of old floorboards and Kate seemed always to have had a giant saucepan magically generating lentil dahl on an ill-at-ease and isolated-looking cooker. There were no kitchen units and, at first, no hot water. There was, however, an electric radiator but this fused the system, bestowing blackouts without warning. Fortunately, the kitchen looked fantastic by candlelight. The walls were of peeling paper, plaster and paint and the effect veered uncertainly between Italian Renaissance and French farmhouse.

Early on, Richard declared that he “couldn’t live in such a heap” which turned out to be another of his precipitate and theatrical statements. After I’d hung a large oil painting by Adrian Ryan The village street, Montauroux the energy tilted in favour of Provence. As I grew more acquainted with that artist, came more transformational works on loan to Sutton House. And how many times, on opening the door, did I find an array of candlelit faces regarding me beyond a vase of flowers and a wafting aroma of stew?

11 October 1988: “When Mike and I came to select our bedrooms he waited, conscious of a pecking order, while I chose the smallest one. It was a future precaution against the cold. Some squatter’s depiction of a revolting eyeball figured large on its red wall. Sinister and badly painted, I couldn’t understand the Trust saying it needed preserving – they didn’t have to live with it – and a photograph would have served more purpose. I hung a 1920s Mexican blanket over it. Later I defied their instruction, covered it with lining paper and painted it white. I also bought lovely period furniture for that room, which later still became the upstairs kitchen, a carved blanket chest, a Victorian button-back chair and a ‘Bed-knobs & Broomsticks’ bed, bought for purposes of seduction which worked out well. Mike told me how discreet I was, having scarcely noticed anything going on. He’d chosen the sunniest room furthest away, perhaps the largest, certainly the warmest and unfailingly the untidiest. The large cracks in his floordrobe were the sole means of aerating it.”

Judy’s room, made coolly elegant, was north-facing and opposite Mike’s at the end of the long corridor which I claimed to hang paintings. This was where the landline telephone was put. From there, three minutes away and two flights down in the kitchen, we were not certain to hear either it or the bell by the front door. Guests would arrive, hammer with their fists and be reduced to telephoning from the nearby call-box. The old house rather amused itself by keeping the 20th century at bay.

People often ask me for my Sutton House ghost stories and there were many more than I can list here. The best known was one “The white lady” who’d apparently died in childbirth in the 18th century.

This is from 12 December 1988:

“I stood facing west in the top corridor facing Judy’s friend Nick halfway down. He was saying something, but I was distracted by a moving shape of light behind him. I’ve seen the mime artist Lindsay Kemp move imperceptibly and it reminded me of that. The inverted rectangle of light was about five feet tall. It appeared out of the left wall and eventually merged into the right. I felt and heard nothing, but what I wanted was to stop Nick talking, point, and to tell him to look behind him, but I found myself freeze and unable to.”

Not everything along that corridor was what it seemed. Once when my sister was visiting and seeking to inspect the latest artworks, she advanced toward a photograph by Matthew R Lewis taken for the 80th birthday of Quentin Crisp, then stopped, looked closer and turned: “Is that a portrait of our grandmother?” she asked.

And this is another from 8 February 1991:

“A very obedient sheepdog called ‘Boy’ stayed for the weekend. On his first day, he suddenly grew agitated in the kitchen, as though sensing a cat outside. He began snarling, whining, darting up to and around an empty space. Moreover, in his agitation, although he was the best-trained collie I knew, he refused all commands to come, sit or be quiet. It ended with no one wanting to be left alone in the room.”

People came twice “to exorcise the spirits trapped between worlds for the good of the house.” Afterwards, they played the tape of their work to Kate and me. There had been four spiritualists and a fifth working as a trance medium, whose voice served all of the “tormented souls” manifesting one by one, from differing times, origins, accents and sexes. The exorcisms were high octane, also referencing floggings, flagellation and other goings-on.

But almost invariably, the house was a homely, welcoming place to be. This gave rise to various summer parties. After one of them, I remember an intelligent, well-known model at that time who, said with eyes shining: “It’s the best party I’ve been to in a long time.” I believed him, because I felt the same. He was also responding to the energy of the house.

Among my regular visitors was the post-Mapplethorpe photographer, Matthew R Lewis, who lived around the corner. His black and white images fitted darkly with the house where several of them were taken. Lewis brought his eclectic friends and sitters, including Derek Jarman, who he was often with. Sir Norman Rosenthal was another, who was overly preoccupied first by the walls’ wearied fabric and kept repeating “most amusing”, then by our heating system. In fact, the house had been very warm while the electricity had been free, to bone-chillingly cold when that perk had come to an end. Even when the outside temperature would rise overnight, the inside would only follow in painful slow motion. This had one advantage: cut flowers bloomed for an amazing duration.

I think now on friends, many of them departed; on the luxury of wandering through the empty rooms at night, including the courtyard, reading aloud, or else just listening to arrows of rain falling on the courtyard portico. For Richard, there was even a full stage in the Wenlock Barn where he rehearsed auditions for more than one West End musical in which he came to star.

Richard didn’t take up the invitation last month, 30 years on, to revisit Sutton House and revive the past, but here’s a taste of what all the others had to say:

Kate, now 58, is an architect in the same firm that restored Sutton House, although she co-established her own practice in between. She has three adult children and lives in Oxfordshire.

“Tales I’ve told my children seem to have been mostly of ghosts, including about the strangely un-biddable sheepdog,” she says. “Or the real-life occurrence of a man wielding an axe and trying to gain access to the inside. My wedding party was held overnight in the Great Chamber, in 1989, starting at 11pm and ending at 7am to beat the lack of night-time transport in those days. We’d dressed the room beautifully. There were 40 dinner guests and Scottish country dancing after. The plan to play murder in the dark failed because when the house lights were turned off, everybody was expected to move, but instead there was silence, so I switched on the lights and everyone had frozen, too freaked to take part.”

Judy, now 59, has also worked for the same architect’s practice ever since we lived in the house. It was her first job since qualifying. She was five when we met and went to school in Cranbrook, Kent, near to where she lives now.

“I’d scuttle the long route through the cold and dust from my room to the kitchen – because a section of stairs down to the President’s Room was then missing,” she says. “I cleared the earth behind the house to grow tomatoes and flowers along the back of the Wenlock Barn. I was astonished by the creation of the garden from the old Breaker’s Yard. And I can’t forget watching the Hillsborough tragedy unfold on our black and white TV.”

Mike, 64, was a student nurse and a nightclub manager before that. He’s still a registered nurse, but now works in hospital management and is a commercial songwriter. He has three teenage children and lives in Acton.

“We lived through discoveries like the hidden fireplace beneath my room by the English Heritage experts and were the first to hear of them,” he says. “It sparked my interest in architecture and I remember feeling glad when the linenfold panelling was reinstalled. Like nowhere else in London, the rooftop seemed like being in southern Europe, always under immense skies.”

I see in Sutton House now its humanity, its warm persona evidenced as strongly as before. That its staff love working there is no surprise. I asked for us to be taken up to the former gallery, our bedroom corridor, that’s closed to the 20,000 mostly local annual visitors. It’s not currently a beautiful space, but as we all trooped beyond the locked door, we let out a spontaneous and collective “Ooo-oh!”.

The Breaker’s Yard Garden is the new miracle. It was made by Queer Botany, working with the artist Daniel Baker and paying homage to Derek Jarman, despite not knowing of his past connection to the house. To me, it sums up how Sutton House has thrived in our absence.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments