World wildlife trade: Mad, sad and extremely dangerous

The natural world is being plundered at unsustainable rates to meet demand from Asia – but Europe and the US are guilty too, writes Jane Dalton

This pandemic is the consequence of our persistent and excessive intrusion in nature, and the vast illegal wildlife trade, in particular the wildlife markets, the wet markets of south Asia and bushmeat markets of Africa,” tweeted the actor Peter Egan. “It’s just a matter of time before something like this was going to happen.”

The coronavirus pandemic has thrust the global wildlife trade into the world’s gaze as never before, horrifying much of the western world with photographs of caged raccoons, civet cats, reptiles and birds, carcasses of bats, pangolins and alligators, openly sold in the streets of southeast Asia and India.

But worldwide trade in wild animals and their body parts is much wider still than these grisly open-air markets, and three-quarters of emerging viruses are spread by humans’ interference with animals.

The world’s wildlife trade is massive – and growing. Indeed, financial experts have judged wildlife crime to be the fourth largest international crime after drugs, forgeries and human trafficking.

Almost any creature may be bought and sold, and almost every country of the world is involved, whether as a source, a buyer or a transit nation. Wildlife is traded alive or dead, in parts or whole; the trade may be legal or illegal, and it happens within countries or across borders, at markets and online.

Animal carcasses and parts are bought and sold for meat, supposed medical treatments, for the pet trade or for futile trinkets.

Some species are being plundered so much that, under extra pressure from habitat loss and the climate emergency, they are nearing extinction.

Obtaining accurate up-to-date figures giving a complete picture of this vast business is near impossible as so much trade goes undetected or unrecorded, and quantities sold vary all the time.

But information from Cites – the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, which regulates legal transactions only – suggests that traffic steadily rose between 1975 and 2016, reaching more than a million trades annually for the first time in 2012.

A 2013 Bioscience report found that illegal wildlife trade accounted for more than half of trade reports – 59 per cent – with legal trade 41 per cent.

Virtually every country in the world plays a role. Suspected traffickers of some 80 nationalities have been identified, illustrating the fact that wildlife crime is truly a global issue

The same proportion of sales were international, and 41 per cent within the same country. Transit countries were usually Asian, while the countries that bought most items were in Asia.

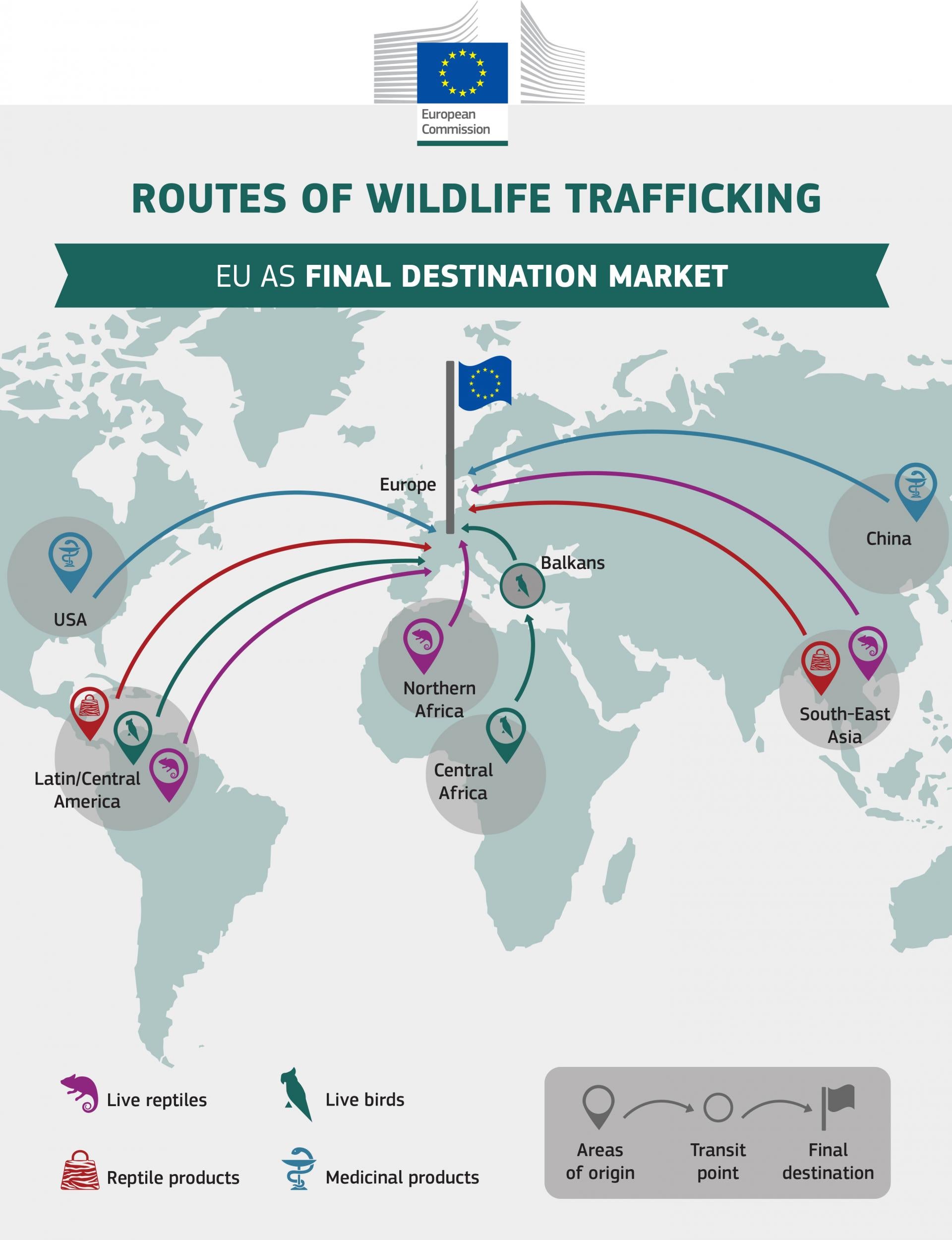

But in Europe we’re guilty, too: Europe and North America were the second and third biggest buyers respectively. Countries in both Africa and Central and South America were bigger suppliers than consumers, whereas those in Europe and North America were larger consumers than suppliers.

Legal trade

Many people understandably assume that the world’s precious species are protected in law from being bought and sold.

But under Cites rules, that’s often not the case, and conservationists disagree over whether legal trade exacerbates illegal trade by fuelling demand or protects species from worse pillaging.

Either way, it’s no guarantee of welfare. Research published last year by Cambridge University Press found legal trade in live specimens was primarily from captive-produced, artificially propagated or ranched sources, whereas traded meat was primarily wild-sourced.

This time, the research found the US was the largest consumer of legal internationally traded wildlife – up from third.

As for numbers, the World Animal Protection (WAP) organisation calculated that at least 2.7 million African animals were legally traded internationally between 2011 and 2015. This number represents the top five “big” and top five “little” species either taken from the wild or bred on commercial farms for their skins and as exotic pets.

The “big five” most in-demand and legally sold were African elephants (Cites allows four countries to sell ivory), hippopotamuses, Nile crocodiles, Cape fur seals and Hartmann’s mountain zebras.

Nile crocodiles are intensively farmed for their leather, with at least 189,000 skins sold each year, the charity said. They often end up as bags and boots in upmarket and designer stores. In Namibia, thousands of Cape fur seal pups are rounded up, clubbed and suffocated every year in Namibia, WAP reported. The adults are shot or clubbed, all for their fur. And when elephants are killed for their ivory and their skins, bullets may miss their mark, leading to “a prolonged and agonising death”.

The “little five” most popular species legally sold as exotic pets were ball pythons, African grey parrots, emperor scorpions, leopard tortoises and savannah monitor lizards.

More than half a million ball pythons were sold between 2011 and 2015 alone, most shipped to the US, destined to live in glass tanks. A total of 289,006 African grey parrots were sold from Africa for the pet trade in the four years studied, usually kept in cramped boxes during transport.

Since that study, demand is not thought to have been curbed. No wonder, then, that scores of conservation and environmental causes around the globe have joined forces to petition countries’ leaders to halt the wildlife trade, legal as well as illegal.

Ilegal trade

There is no real dividing line between legal and illegal wildlife trade since a lack of watertight checks allows poachers and traffickers to pass off illegal products as legal. Certain reptile skins illegally sourced from the wild, for instance, may enter international legal markets and the fashion chain.

Cites reckons that for about 3 per cent of species, commercial international trade is banned, and for about 96 per cent global sales are regulated.

Rising demand from wealthy buyers, predominantly in Asia, has fuelled demand for items made from real skins, ivory and other animal parts, as well as supposed medical cures. Despite years of efforts to tackle poaching, it is still devastating wildlife, particularly in Africa, threatening the existence of much-loved rhinos, elephants and big cats.

Authorities have long recognised that illegal trade is linked to organised crime, including money laundering, drugs and weapons smuggling. Wildlife trafficking in central Africa is even fuelling conflicts and threatening regional and national security by providing funding to militia groups, according to the UN Security Council.

From a poacher’s point of view, law enforcement is less strict than for other crimes, so the risk of punishment is low in most countries.

In numbers, after pangolins, the world’s most trafficked animals and animal parts are of elephants, helmeted hornbills, leopards, rhinos, snow leopards and tigers, according to TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network.

Most of the illicit produce comes from west and central Africa, where, Cites says, both “organised and opportunistic poaching occur”.

Poachers are usually local people recruited by crime syndicates, and exporters were found most often to be Asians living in Africa and sending goods back to their homelands. Vietnam, in particular, has a big consumer market for ivory and rhino horn.

Pangolins are hunted for their scales, which are used in “medicine”, with seizures from Africa destined for Asia increasing 10-fold since 2014, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). By the time numbers not seized are counted, the real number traded is thought to be in the millions.

And because breeding pangolins in captivity at scale is currently not possible, poaching can lead only to extinction.

Traders in west and central Africa report that pangolin traffickers often use the same routes as for ivory. WWF estimates more than 20,000 African elephants are killed annually in countries such as Mozambique for ivory trinkets, but thanks to increased protection last year international researchers judged numbers to have declined to 10,000-15,000.

Rangers also had some success in the hot spot around Malawi and Zambia, last year seizing more than a ton of ivory and arresting 75 suspected ivory poacher-traffickers over 16 months to December.

Meanwhile, young elephants are illegally captured and forced to work entertaining tourists in Thailand, Indonesia, Japan and even Canada. Some are trafficked from Laos to China for the tourist industry, and others are flown to the Middle East.

Asia’s wild tigers are dangerously close to extinction, with fewer than 4,000 globally. However, more than 8,000 are held in captive facilities in China, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam and South Africa. Investigations have shown that many such “farms” breed and slaughter tigers for the illegal trade. Lions, too, are farmed in China and South Africa.

But sellers wouldn’t have a market without buyers and brokers, who are everywhere, and, just like legal wildlife commerce, Europe is not immune from supporting illegal trade. “Virtually every country in the world plays a role,” the UNODC reports. “Suspected traffickers of some 80 nationalities have been identified, illustrating the fact that wildlife crime is truly a global issue.

“All regions of the world play a role as a source, transit, or destination for contraband wildlife, although certain types of wildlife are strongly associated with each region. Birds are most strongly associated with Central and South America; mammals with Africa and Asia; reptiles with Europe and North America.”

Indeed, keeping exotic reptiles as pets has led imports into Europe and the US to soar since 2000, with millions now traded across legal lines.

According to the EU Commission, almost 2,000 live reptiles were seized on EU borders in 2015; millions of glass eels are illegally exported from the EU to Asia every year.

In just five weeks last year, a coordinated blitz by authorities worldwide on wildlife crime led to the seizure of 4,400 live animals, including 20 crocodiles and alligators, 2,700 turtles and tortoises, and 1,500 snakes, lizards and geckos, Interpol said.

Cites says interviews with poachers and enforcement officials in source countries suggest that middlemen are often successful businesspeople, military officials or “others in positions of authority, who by virtue of their position, are less likely to be questioned by law enforcement”.

In tackling illegal wildlife trade, WWF’s priorities include closing tiger “farms”, closing ivory markets and improving national ivory action plans and pressuring Vietnam to strengthen regulations on ivory and rhino horn.

When we talk about wildlife trafficking, we just think, ‘Oh, that’s wildlife’. But it’s millions of individuals who can suffer, feel pain and despair

Clues to the most commonly used routes for illegal wildlife and products came in a report called Runway to Extinction, which said they often follow air passenger routes from hub airports near supply markets in the southern hemisphere to airports near demand markets in the northern hemisphere. “This could be a result of large middle classes in North America, Europe and certain Asian countries creating significant demand for live animals and wildlife products sourced from remaining pockets of biodiversity in South America, Africa and Oceania,” it said.

Of the countries that had the most cases of trafficking by air in 2016-18, China came out on top by a long way, with more than three times as many instances as second-placed Vietnam; followed by Thailand, Indonesia, South Africa and Mexico. The United Arab Emirates was seventh, then Malaysia, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

As well as mammals and reptiles, a huge worry for conservationists is the illegal trapping and killing of migrating songbirds. Every autumn hundreds of thousands of dead birds are sold on the black market to restaurants in Cyprus for a dish called ambelopoulia.

The gangs target migrating blackcaps, robins and garden warblers that fly between Europe and Africa, using electronic calls to lure them into nets.

At a British military base on the island, authorities and conservationists have reduced numbers illegally trapped from around 880,000 in 2016, but even so, last year 117,000 were still killed.

Elsewhere, wildlife poachers have woken up to the possibilities of the internet, and have shifted swathes of commerce online.

An investigation by the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) in France, Germany, Russia and the UK over just six weeks identified 11,772 protected wildlife specimens offered for sale in 5,381 advertisements and posts on 106 online marketplaces and four social media platforms.

Body parts and taxidermy from cheetahs, leopards, lions and tigers as well as live big cats were being sold online.

“Shockingly, we also found over 150 live primates for sale, as well as rhino horn products, ivory and suspected ivory, and elephant feet, skin and hair products – all available to buy over the internet,” IFAW reported.

Four in five items being sold were live animals, mostly reptiles, demonstrating the popularity of exotic animals as pets. Tortoises and turtles accounted for nearly half of all animals sold. Almost a quarter of the rest were birds.

In the UK, the researchers found large numbers of birds and owls for sale, including African grey parrots. Last year a different investigation revealed how the parrots are captured from the wild and stuffed into crates to be flown abroad; three in four suffocate or die of starvation or disease.

The Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online has worked with tech giants to get listings for endangered and threatened species and their products removed.

The Independent, which is campaigning for tighter restrictions on wildlife trading, has seen estimates of the mind-boggling sums the world’s illegal traffickers and brokers make – but is not publishing them because conservation demands the value of wildlife should not be judged in monetary terms.

The real worth of the world’s living species is a healthy biodiverse planet, with an ecosystem capable of supporting and healing us, not killing us. As Jane Goodall said: “When we talk about wildlife trafficking, we just think, ‘Oh, that’s wildlife’. But it’s millions of individuals who can suffer, feel pain and despair.

“We need to respect the natural world. We can’t go on and on taking natural resources for economic development on a planet with finite natural resources.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments