Starmer, Corbyn and a big-screen Bernie Sanders: Journey to the centre of the Labour conference

The Labour Party conference in Brighton was expected to be deeply fractious, with both sides of the party pulling in different directions. Miles Ellingham was on the ground, moving between the two

The Labour Party conference is made up of two distinct worlds. One is the formal domain of the delegates, media, commercial interests and party politicians. This world is enclosed by security checks and ruled by lanyards. Contained within the Brighton Centre, the Grand Hotel and Hilton Metropole, this is a place of incremental deliberation, where politics is localised – often to a single room – and political leadership makes impassioned, carefully scripted speeches to huge audiences.

The other world looks and feels more like a music festival. Just down the road at the Old Steine Gardens, within large colourful tents, an education project called The World Transformed (TWT) sets up a space for the young, the radical and the alienated of the left to come and participate in politics.

During the Corbyn years, these two worlds, one organiser told me, had felt woven together – now, however, that connection has been severed. Leaving the station and stepping on to Surrey Street, the very first words I hear come from a young woman selling a copy of Socialist Appeal: “This is the paper Starmer doesn’t want you to read!”

This is shaping-up to be a deeply fractious week for the Labour Party. The leadership had invited a conflict even before the conference began with its bid to reform the ‘one member one vote’ system for electing a party leader, drawing power away from a membership still largely faithful to Jeremy Corbyn – himself suspended as an MP and no longer welcome on the conference floor. Keir Starmer also publicly abandoned one of the 10 pledges that got him elected as party leader, refusing to commit to nationalising the “big six” energy companies on the Andrew Marr Show.

To make matters worse, delegates from Liverpool are outraged that journalists from The Sun have been allowed to attend the event. One of them takes to the stage on the opening day to tell a packed conference floor: “I’d like to know why the CAC [Conference Arrangements Committee] has allowed Murdoch’s lying Tory rag to come to this conference!” She receives rapturous applause. Following her, someone from the Community Labour Party takes to the stage and asks: “How can we work without money?” The party is in dire economic straits after a disastrous election defeat and a rocky relationship with its top union backers.

All this is new to me, the architecture of a political machine. The trade unions have their booths front and centre, reps from media channels, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and political wings shower passers-by with leaflets, and high powered journalists hover like kestrels in a headwind, awaiting prey. The GB News hub is, of course, experiencing technical difficulties and a small flock of anti-vax activists are accosting people outside.

Ten minutes down the road, in TWT’s big tent, a panel is discussing “socialist strategy after Jeremy Corbyn”, Repeater Books has a stall selling work by cultural theorist Mark Fisher, and in another smaller tent a group are leading a working-class-struggle sing-a-long with renditions of “Blackleg Miner” and The Chartist anthem. Everyone is excited about this evening when John McDonnell will be joined in conversation by senator Bernie Sanders, Zooming in from his desk in Washington DC.

Before that, however, I’ve arranged to meet Ian Lavery at the Unite hub in the main conference hall. Lavery, the MP for Wansbeck, Northumberland, is a walking manifestation of the traditional Labour Party. He took over leadership of the National Union of Miners from Arthur Scargill and almost had a physical altercation with Boris Johnson when the now-prime minister blew kisses at him in the backroom of a BBC leader’s debate in 2017. He’s a victim of Labour’s strife in the north of England too; with red wall voters abandoning the party, his own majority fell to just 814 votes (2 per cent). Before we sit down, I ask if he’s enjoying the conference – he growls.

The 2017 election saw a surge in Labour’s youth vote, and young people did much of the campaigning on the ground at the last two elections, trudging door to door in the rain

“People are not sure what we actually stand for,” he tells me, “and we’re a fair way off ever getting the keys to Downing Street. Starmer’s scored an own goal trying to rush through rule changes which have dominated the headlines. We should’ve been talking about the ‘new deal for working people’ which Andy McDonald produced… It’s not a left-right thing either, people on the right of the party are upset at this as well.”

When I ask Lavery about his shrinking majority, he tells me that he’d seen this shift coming the moment Labour started gesturing towards a second referendum on Brexit. Apparently, he’d raised these concerns with Starmer – then Brexit secretary – but Starmer had dismissed them. Pressed on his political precarity, he shrugs and tells me “politics is politics” and that he’s more worried about his constituents’ quality of life.

Back at the conference, David Evans, from the right of the party, is approved as general secretary. Taking to the stage, victorious, he asks delegates: “Everyone remembers why they joined Labour. What was it for you?” The response, not for the last time this week, is a dissenting “Oh Jeremy Corbyn!”

In the evening, I join a throng of mostly young activists to watch McDonnell and an enormous Bernie Sanders on a screen above his head. Together they discuss how to promote left ideas within a broad-tent party and build a mass movement. At the end of the talk, a Young Labour activist tells Sanders how depressed she feels at her “limited political horizons”. “I’m sorry,” the senator responds. “My generation has let you down.”

The rest of the night is spent downing pints of cheap Guinness with a crowd of Trade Unionists, CLP delegates and left-wing publishers. In 1982, Ken Loach – who was ejected from the party in the summer – released a documentary called The Red and The Blue, a fly on the wall diptych of the 1982 Labour and Tory conferences. His depiction of the Labour conference features a montage of loud Irish pubs, with men in old, tweed jackets arguing over socialist ideals. It is nice to see that an adapted version of this tradition still persists in the back-streets of Brighton.

The 2017 election saw a surge in Labour’s youth vote, and young people did much of the campaigning on the ground at the last two elections, trudging door to door in the rain, driving up the vote. However, Starmer is seen to be ignoring them – at least, that’s the sentiment at TWT.

One figure who’s been adept at communicating with young people is Ash Sarkar, the senior editor at Novara Media. I meet with her on Sunday in the basement of a cabaret venue. Sarkar laments Keir Starmer’s conception of politics “as a series of empty rhetorical gestures” and how he “speaks differently to the Labour membership then he does to the rest of the country”.

By contrast, she says: “Corbyn saw that young people are over-represented in precarious work, that they’re laden with debt if they go to university and excluded from jobs if they don’t. Corbyn saw that they’re treated essentially as a cash-cow by a parasitic rentier class. He took their material interests seriously.” After the interview, we watch the north London derby together. Sarkar is a lifelong Tottenham fan and her mood darkens as Arsenal go 3-0 up in half an hour.

Much of the Labour conference is defined by fringe meetings, which spring up haphazardly in hotel conference rooms and clubs. These events range from promoting proportional representation (this has a large swathe of support, including from MPs Clive Lewis and Stephen Kinnock) to stopping “fire and rehire”, and supporting the Palestinian struggle. Conference news will often trickle in during these panels. At an event called Labour for a New Democracy, the room hears that Starmer’s leadership ballot rule changes have been approved with last-minute backing from Unison – there are stifled groans.

Sunday ends with probably the strangest event of the conference – Dawn Butler’s dancehall night at PRYZM, an incredibly kitsch nightclub on the seafront. Passing security and entering down the neon-lit stairwell, I spot a wobbly-looking Barry Gardiner, Corbyn’s shadow trade secretary, on his way out. Thirty minutes later, the mayor of London drops in to hype the DJ set, keeping good on his election promise to go clubbing after the pandemic rules relaxed.

Monday is the most dramatic day of the conference and begins with a pivotal speech from Rachel Reeves, the shadow chancellor. Her speech touts the achievements of Labour’s record in government and decries the “cronyism” of the Tories as she promises to be the “first green chancellor” and pledges £28bn of investment every year to fight climate change. It’s well received, though there is no mention (yet) of a Green New Deal, a motion that conference had backed the day before. Exiting the hall, I can hear delegates whispering angrily about this at the bar.

Over in the other world, Paul Mason, on a panel called “How Can Labour Win?”, is being asked to apologise for his role in supporting the People’s Vote campaign. Following that, under the guise of a question, one attendee from Merseyside gets up and shouts out something close to a spoken-word poem, ending in the words “Labour is dead!” Later, during another panel, simply titled “Starmer Out! And If So, How?” news breaks that Andy McDonald has resigned as shadow employment minister, accusing Starmer of not honouring the pledges he made to members in his leadership campaign, and not supporting McDonald on a £15 minimum wage. Cries of “for shame!” ripple through the crowd.

This lack of support from the leadership for upping the minimum wage enrages much of the conference, who see it as antithetical to the essential purpose of the party and deeply hypocritical. A photo taken two years ago of Keir Starmer at a protest backing a £15 minimum wage for McDonald’s fast-food workers quickly goes viral.

All this sets the stage for a rally organised by Tribune magazine in the Old Market. This includes impassioned speeches from Rebecca Long-Bailey, Zarah Sultana, Dave Ward (head of the Communication Workers Union), John McDonnell and Corbyn. It also includes a surprise appearance from Andy McDonald, fresh from his resignation, who urges Keir Starmer to “tell the truth about what’s gone wrong and be bold about how to fix it…” The audience roars and McDonald leaves the stage to chants of “Andy! Andy! Andy!”

However, far and away the most dynamic speaker on the bill is Nina Turner, a state senator from Ohio who in March narrowly lost a special election to Congress. Turner whips the crowd into a frenzy, following the tradition of American gospel oratory. She quotes Harriet Tubman: “If you hear the dogs, keep going. If you see the torches in the woods, keep going. If there's shouting after you, keep going. Don't ever stop. Keep going.”

Turner amends the words to fit the current Labour Party moment: “If the leadership change the rules, keep going!” I caught up with Nina at her hotel the following day, where she tells me that the activists in Brighton remind her of America in the 1960s. “When you’re trying to motivate people to do things that seem insurmountable,” she says, “you’ve got to drench them in hope... I want your readers to know, in the words of Shirley Chisholm, that ‘service is the rent we pay for our time on the Earth’ and that – fancy title or not – nobody has the right to sit on the sidelines.”

She ends the interview telling me she’s excited to try a Greggs vegan sausage roll.

When I ask him to describe the conference in a word, he thinks about it for a second and replies, ‘Chaos’

Labour in Brighton could certainly use some of Senator Turner’s hope. A through line of the five days is the consistent entrenchment of its now warring factions. Starmer seems to have taken the Kinnock playbook to heart, divorcing the left in an effort to come off as a “serious” party, rather than the Biden approach of working with them and engaging with their policy ideas. Each day of conference, the conflict within the party seems to calcify. At the Tribune rally, John McDonnell declares that he and Corbyn hadn’t wanted to “do to Starmer what they did to us” before concluding, “Well, sod that for a laugh.” This invites a thunderous standing ovation.

On Tuesday, though, Jonathan Ashworth delivers a speech offering a “national care service for the 21st century”. It’s a radical idea and surely popular. The party just needs a few more of them to emerge from Starmer’s leader’s speech the next day. Few of the delegates seem to expect that, though. Indeed, over the Guinnesses that night a broad, elderly union delegate tells me in a low voice that there’ll be trouble during the speech, perhaps even a mass walkout.

I head to the Grand to meet John McDonnell. Unable to find a quiet room, we conduct the interview on one of the hotel’s ornate Victorian stairwells, McDonnell whispering his answers into my recorder. When I ask him to describe the conference in a word, he thinks about it for a second and replies, “chaos”. McDonnell is frustrated that Starmer still hasn’t restored the whip to Corbyn – something Gardiner had also suggested as an olive branch. “We’ve had enough division over the last few days,” he says. “We’re losing time.” McDonnell then seems to walk back his “sod that…” comments of the night before. “I think it’s time to be frank and public about where we go from here and if we have criticisms we need to be voicing that firmly.”

Later that day, Corbyn comes to the Steine Gardens where he is greeted with adoration. On his tour of the bookshop and stalls, activists queue to shake his hand and thank him for politicising them. Wherever he moves, groups of admirers follow. Corbyn stops to speak to anyone who wants to meet him, happy to pose in what seems like hundreds of selfies.

I manage to speak to him as he is leaving, and ask how he feels being ostracised from the party he has been a member of since 1966. “You know, it’s the first time since the 1970s that I haven’t been on the floor of the conference,” he says wistfully. When I ask if he’ll be in attendance in any capacity at the leadership speech he says no, “I’ll be in London tomorrow doing a Council of Europe speech on the environment.” His one-word description of conference is “confusing”. That evening the heavens open and the Old Steine Gardens fill with mud.

Wednesday morning comes and all attention is on the leader’s speech – the climax of the official conference. All year, Keir Starmer has complained that the pandemic has stopped him speaking directly to the public and memberships. Now his chance has finally come. A chance, too, to put forward actual policy. There is an air of trepidation. We all know he’ll be heckled, but not the scale of the heckling or how he’ll be able to deal with it.

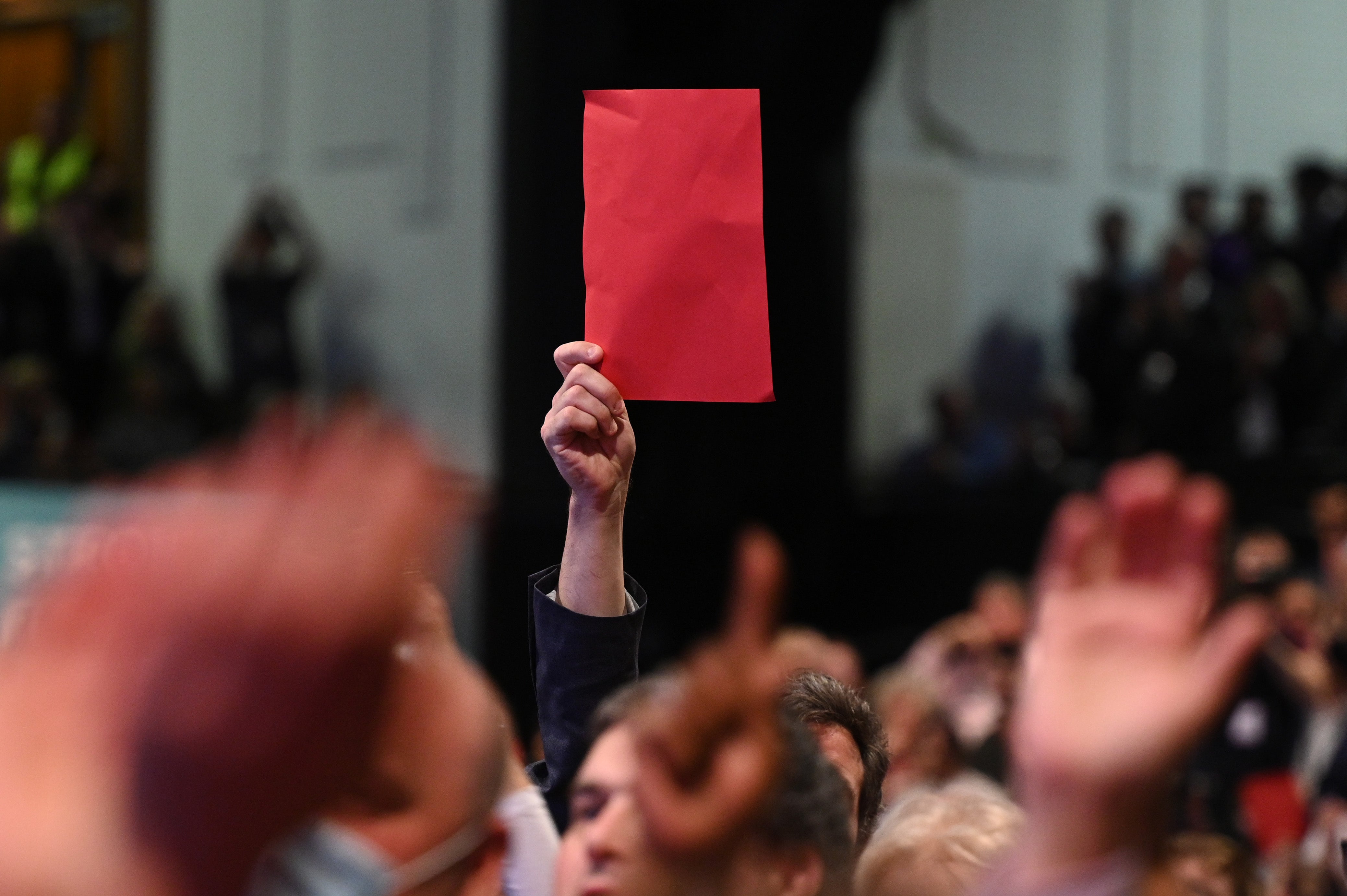

They start immediately. As soon as the leader starts speaking a man on the balcony begins chanting “Oh Jeremy Corbyn!” and it is not long before the first calls for a £15 minimum wage follow. But there is no mass walkout and Starmer moves past the interruptions. At one point, he even rebutts them directly. “Shouting slogans or changing lives,” he retorts combatively.

The speech itself is incredibly long. Starmer has a liking for lengthy political declarations, having published a circuitous 11,500-word pamphlet for the Fabian Society the week before. The speech is full of emotional anecdotes: stories from his time as a lawyer, about his parents, about losing his mother at a young age.

He frames himself as a “tough on crime” leader, takes swipes at Sturgeon’s SNP and Corbyn’s previous manifesto and champions the achievement of the past Labour government. There is some policy, though, and commitments on mental health, education, healthcare and a green new deal. The problem is, he’s deliberately narrowing the ambitions of the Labour Party, moving it away from the radical proposals of Corbyn. As the speech nears conclusion a delegate holds up a sign saying “No Purge” and another attempts to violently tear it away. When it ends, as ever “The Red Flag” is sung, echoing a little half-heartedly across the hall, followed by “Jerusalem”, then Fatboy Slim.

As conference finally comes to an end it is impossible not to sense that the party has changed fundamentally. Starmer has chosen to move away almost completely from Corbyn’s legacy in a bid for power. He has said this on the Andrew Marr Show on Sunday: he is more interested in winning than unity. But what will that power mean without transformative policies or an inspired membership? At conference, I have seen two competing worlds: one with all the power but none of the energy – another with all the energy but none of the power.

Starmer perhaps doesn’t sense this, perhaps doesn’t see it as a problem. But unless he can unite the party with a coherent, socialist vision of the future, the twin worlds of conference will drift ever further apart. Finally, I leave to catch the train, looking back one last time towards Brighton’s flat horizon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

18Comments