Mr Jones: The story of Stalin’s worst atrocity finally gets told

A young Welsh reporter Gareth Jones witnessed firsthand the deliberate starvation of three million Ukrainians. Stalin’s state-controlled genocide is now the subject of a new film, reports Stephen Applebaum

The Holodomor was one of the greatest human-made catastrophes of the 20th century. In between the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust, more than three million Soviet Ukrainians were deliberately starved to death by Stalin’s government, in the midst of an ideologically rooted famine that covered large swathes of the Soviet Union. The famine of 1930-1933 began as a consequence of Stalin’s Five Year Plan of Industrialisation and Collectivisation.

Peasants were driven from their farms and made to join larger state farms; food shortages and hunger ensued. Stalin then deepened the crisis in Ukraine by executing his plan to eradicate the so-called Kulaks, a demonised class of prosperous peasants scapegoated by the state as the cause of hunger in Russia. Deprived of their grain by Moscow, harried by police units who raided their homes for anything edible, and prevented from leaving the republic, Ukrainians found themselves fighting terrible odds to stay alive.

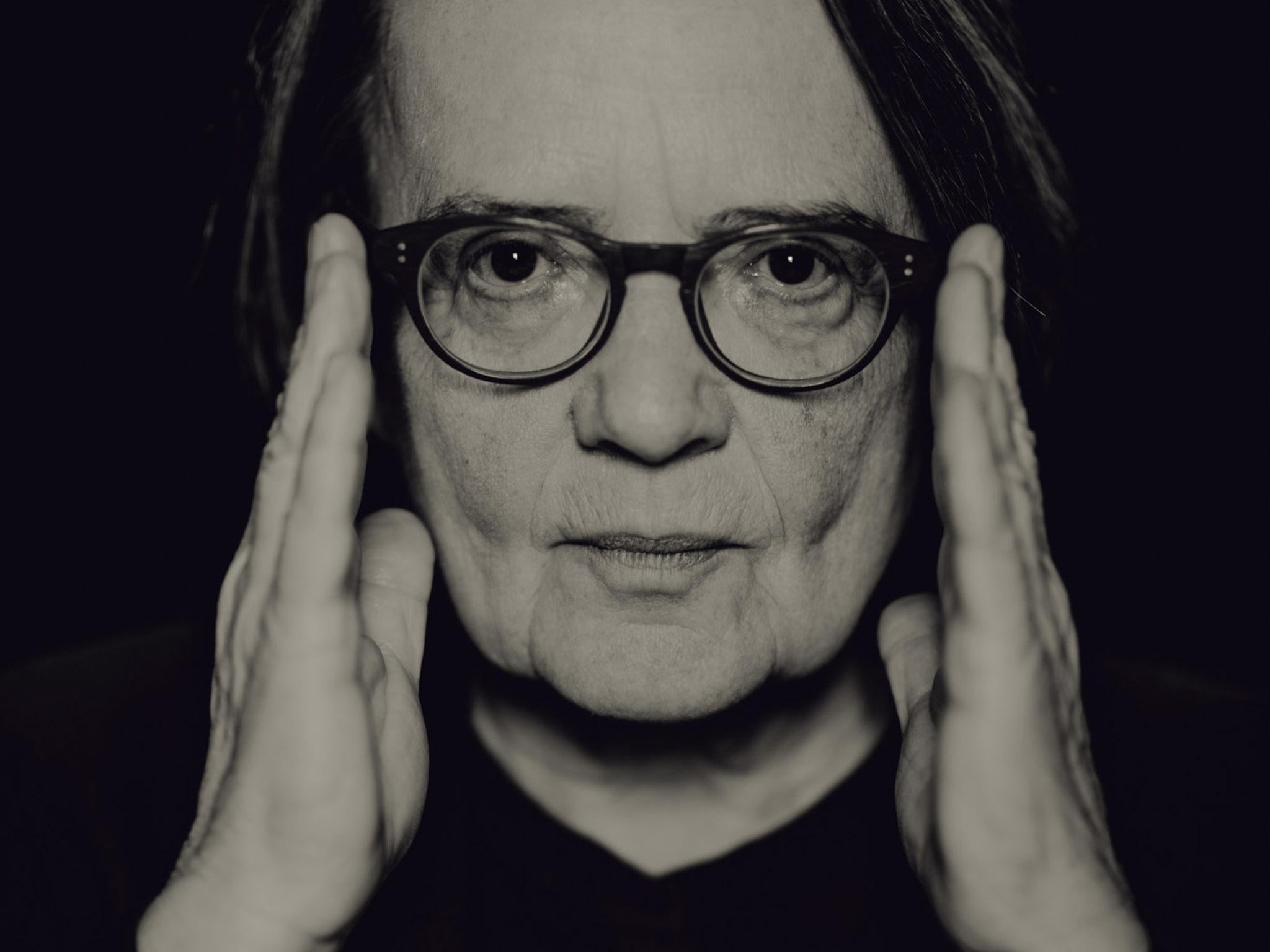

As it was unfolding and for years afterwards, the Holodomor barely impacted on people’s consciousness outside Russia. How this was made possible is now the subject of Mr Jones, a compelling and timely new film from the Polish director Agnieszka Holland and American screenwriter Andrea Chalupa.

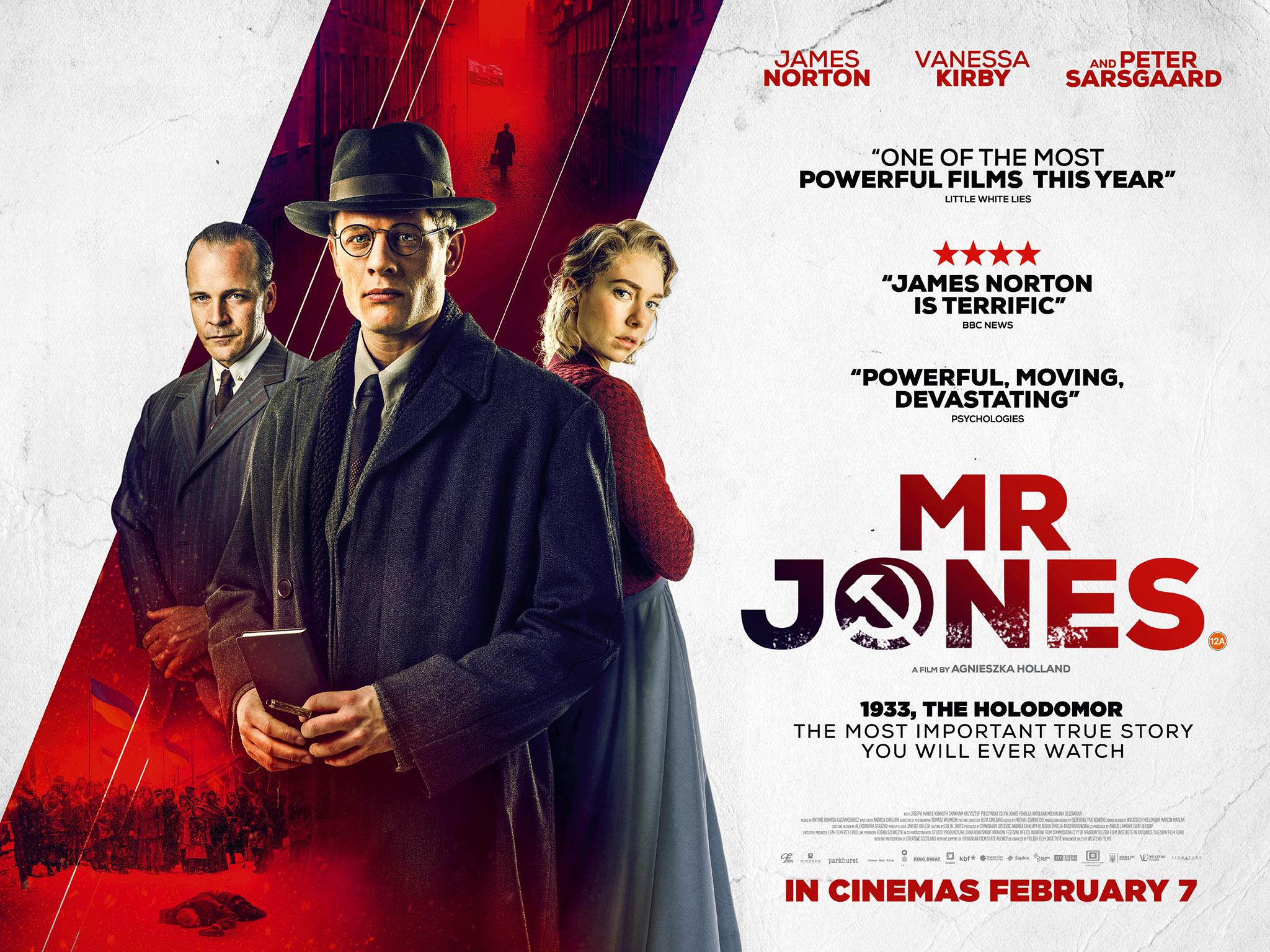

Inspired by real events, the tale of how the Welsh reporter Gareth Jones challenged the conspiracy of silence surrounding the famine isn’t simply a piece of aspic-coated history, but a thought-provoking window on to our current struggles with authoritarianism, and the battle between truth and lies, real news and fake news, facts and “alternative facts”.

Although technology has enabled lies to travel round the world faster than ever before, the disinformation tactics used 87 years ago were the same ones that are applied today, says Chalupa: “You don’t just need to bury the truth, you need to muddle the truth and create so much confusion that people just dismiss it. That’s what happened in 1933.”

And the truth continued to be obfuscated for decades. “What the Kremlin has been doing for generations is, essentially, gaslighting us,” claims Chalupa, on the phone from America. “So the Holodomor is really just now, finally, coming out. And a lot of that is thanks, in part, to the fall of the Soviet Union, and the opening of archives that has allowed greater research and greater access, especially in Ukraine.“

Chalupa is a former student of Ukrainian at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute and the International School of Ukrainian Studies in L’viv, Ukraine. Her childhood in California was filled with stories about the Holodomor and life under Stalin, courtesy of her beloved grandfather, Olexji.

He was born in Donbas, in eastern Ukraine, and was vocal while many other survivors felt unable to speak. For them, says Chalupa, “the fear was so great, it travelled with them”. Olexji also wrote down his entire life in a memoir, which Chalupa inherited. After leaving college, she took it to Ukraine to be translated, and was amazed by what came back: it was like reading Animal Farm as seen through the eyes of someone who had experienced the events George Orwell allegorised in his classic novella.

“There were stories about him being a boy during the Russian Revolution; then various things as a young man during Stalin’s famine; and then as a young father being arrested and tortured during Stalin’s purges.”

A horrific moment in the film, when body collectors pick up the corpse of a dead mother and then throw her still-living baby on to the cart of bodies with her, on the way to the mass grave, was taken directly from his eyewitness account.

“Growing up with these stories, I couldn’t really understand how the rest of the world just wasn’t aware of this,” she says. “It was beyond infuriating. And for me to make this film, I just needed to do it. I needed people to know. It was a crazy project. My parents, as much as they supported me being close to my heritage, I think they were extraordinarily nervous throughout the entire journey.”

Chalupa wasn’t just doing it for herself. She wanted to honour the memory of her grandfather and all the other victims of the Holodomor, and make the genocide more widely known. “I was driven because I needed that healing for me, and my family. Countless people had suffered this and I wanted to acknowledge them.

“Something like 100,000 Ukrainians across the country saw this film when it came out. It was a big deal in Ukraine. I was getting messages from friends in Kiev that were overwhelmed by the experience of watching the film, because history is healing.”

Kiev is also where Chalupa came across Gareth Jones for the first time in 2005, while doing research at an internet cafe. Her original plan was to make Malcolm Muggeridge her protagonist. But she stumbled upon a website set up by Jones’s niece and quickly changed tack. The niece, Dr Margaret Siriol Colley, had written a book about her uncle, a largely forgotten man who at the age of 27 had exposed the reality of what was happening in the Soviet Union.

“It was a lightning bolt moment,” says Chalupa: “This is my hero!”

Jones was born in Barry, south Wales, in 1905, and from an early age seems to have longed for a life beyond the horizon. When Chalupa visited his childhood home, she “looked out from his backyard, and you could see the coastline and the water. As a child, he would go down to the docks and interview the sailors ... So, I think he grew up with a sense of adventure and wanted to see the world.”

She suggests this might have been part of why he studied languages. Jones graduated from Cambridge with first-class honours in French, Russian and German, which helped him gain employment as a foreign affairs adviser to the former prime minister David Lloyd George – a connection that would prove invaluable during his trips to Russia.

He had an “independent streak” and his refusal to settle for “easy’’ inspired Chalupa when she felt overwhelmed by the “crazy thing” she was trying to do by making “a historical drama that was very expensive, very complicated”. She finally got her confidence when she went to the National Library of Wales, where the Gareth Jones archive is held, and “read letters that he would write to his parents that sounded so much like me telling my parents to back off and leave me alone.”

She recalls a particularly spiky communication in which “Gareth told his parents, ‘Stop pressuring me. Why would you want a son of yours to take any old job just because of security? What is security? Why would you be proud of me if I would be such a coward?’ For me, that really resonated.”

Nevertheless, there were still moments when Chalupa found the going too hard, and in early 2015, having got no closer to getting the film made, she talked seriously about giving up completely. “I was feeling very pathetic.”

Around the same time, some Russian friends in New York were organising a march in solidarity with the Russian politician Boris Nemtsov’s march in Moscow against Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and just days before it was due to happen, Nemtsov was “assassinated in the shadow of the Kremlin”. The impact was devastating. “Our march turned into a vigil,” says Chalupa, “and I saw my Russian friends completely distraught, looking absolutely lost.”

Nemtsov had been a “Russian hero that united Russians and Ukrainians”. His assassination pushed Chalupa to “redouble my efforts on the project” and write “a very angry version that grabbed the reader by the throat. I wanted just to scream, ‘How can you not care about what’s happening right now? It’s all happening again. This problem with disinformation. The war in Ukraine. History is repeating right in front of us.’”

She sent the screenplay to Agnieszka Holland as her last hope, but was told by people around the director to temper her expectations, as Holland had been rejecting scripts with big names attached. Even so, she said yes immediately. “I think she was just as angry as I was,” suggests Chalupa.

Holland, whose parents were journalists, has firsthand experience of life under communism. When she was 13, her Jewish father – a Polish veteran of the Red Army – died while being held by the secret police in Warsaw under suspicion of treason, a victim of one of the post-war communist regime’s antisemitic purges. His death was recorded as suicide, although some have suggested the involvement of other hands. Either way, “if you’re driven to suicide under a regime, it’s still the regime’s fault”, says Chalupa. “So I know for Agnieszka, these issues hit close to home.”

Jones also died in controversial circumstances, when he was kidnapped, ransomed and then murdered by bandits in Mongolia, in 1935, on the eve of his 30th birthday. His family have always suspected that it was Russian retribution for being the first independent witness to blow the lid off Stalin’s greatest atrocity, and certainly the Soviet connections of people who were with Jones at different points of his journey make for a persuasive case.

“He was the one to come out and say millions – millions! – are being killed,” says Chalupa. “He was the first to say it’s a man-made famine.”

In the same spirit, the makers of Mr Jones didn’t want their film to be just about the past. It takes Jones (played by James Norton) to a fancy hotel in Moscow, where glamorous expats and the Moscow press corps party, and then brings him and the audience face to face with a stark reality outside the city that should make the film’s story resonate beyond its context.

“It grabs the comfortable westerner and pulls you in,” Chalupa says passionately. “It thrusts you into Syria. It thrusts you into Venezuela. It thrusts you into North Korea. It puts you in Crimea. And that’s what we’re really trying to do, which is to remind us that the world is becoming increasingly segregated, income equality is growing, but there are horrors that are happening and they’re real horrors. Families are getting destroyed. Families are getting ripped apart. And children are the biggest victims of all of this.”

Poetic licence makes us discover the famine at the same time as Jones. In fact, he visited Russia on two separate occasions before his explosive final trip there in March 1933, and had already articulated his fears about the famine in 1932, in a two-article series for the Western Mail.

“‘Will there be soup?’,” he asked at the beginning of the first story on 15 October. “That is the question which the men and women of the Soviet Union are asking anxiously, when they think of the rigours of the coming Russian winter. It is a question which is being asked, not only in communist Russia, but also in capitalistic America: but in Russia the voices of the questioners are fraught with greater fear, because the harvest failed and the food is not there.”

When Jones arrived in Moscow for the last time, travel for foreign correspondents was tightly controlled by the state, and entry to Ukraine forbidden. In order to live and work there, a degree of compliance was expected. Words needed to be chosen carefully. In 1929, Paul Scheffer had become the first journalist to be expelled from the Soviet Union for reporting the truth about collectivisation. And it was him, says Chalupa, who tipped off Jones about the famine.

The Welshman was himself a nonconformist and someone difficult to contain. He was the first foreign journalist to fly with Hitler a month after he became chancellor of Germany, and while Jones wrote positively about some of the new government’s ideas, such as its establishment of a Voluntary Labour Service for dealing with the effects of unemployment, he also warned of the Nazis’ threat to the Jews. His report about the “primitive mass worship” he witnessed at a rally, still chills the blood.

“Reading Gareth’s description of the rally while working on the screenplay with the Republican Covention in the background, and Donald Trump on stage saying, ‘I alone can fix it,’ and thousands of people cheering, was just too surreal,” says Chalupa.

Returning to Russia, Jones was told “in a certain embassy” not to go into the villages: “The peasants are starving, and will steal anything they can get hold of.” For a man thrilled by adventure, this only heightened his desire to see for himself what was happening in Ukraine.

He obtained official approval to go there using an invitation to visit the German consul-general in Kharkiv, in the northeast. However, instead of taking the train all the way to his destination, he disembarked early, and spent several days walking 40 miles, unshadowed, through 20 villages, making notes and collecting personal testimonies.

“I tramped through a number of villages in the snow of March,” he wrote. “I saw children with swollen bellies. I slept in peasants’ huts, sometimes nine of us in a room. I talked to every peasant I met, and the general conclusion I draw is that the present state of Russian agriculture is already catastrophic but that in a year’s time its condition will have worsened tenfold.”

Jones didn’t see any dead bodies, but in Mr Jones he not only encounters corpses, but unwittingly eats human flesh. While this didn’t actually happen to him, cannibalism was widespread during the Holodomor, and something Chalupa remembers hearing about as a child.

I saw children with swollen bellies. I slept in peasants’ huts, sometimes nine of us in a room. I talked to every peasant I met, and the general conclusion I draw is that the present state of Russian agriculture is already catastrophic

“I grew up with the story of a mother who was so driven mad by starvation, that she ate her own children,” she says. “Our executive producer on the film, her grandmother was a girl standing on a breadline and she was kidnapped from the breadline, and a group of people had to fight off these men who were trying to kidnap her for food.”

The Ukraine section of the film is disturbing and horrific, but never feels gratuitous. By placing Jones inside the experience, the filmmakers were able to depict more viscerally and intimately an event which, unlike the Holocaust, for example, has rarely been seen in the cinema – and was almost erased from history.

“It was basically to show what the reality was like for those that were suffering through it,” says Chalupa. “We were trying to give people a sense of this sweeping tragedy.”

It is an effective dramatic strategy, but it has drawn criticism from Philip Colley, the great-nephew of Jones, who accused the filmmakers of inventing “multiple fictions” and making “Gareth a victim of the famine, rather than a witness”.

As the latter, Jones faced fierce opposition after he revealed what he’d discovered during his harrowing cross-country trek at a press conference in Berlin, on 29 March 1933, garnering coverage in US and UK newspapers.

“Everywhere,” he said, “was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying’ ... I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farm land in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to see for themselves what is happening ... ‘We are waiting for death’ was my welcome, ‘but see, we still have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. They have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,’ they cried.”

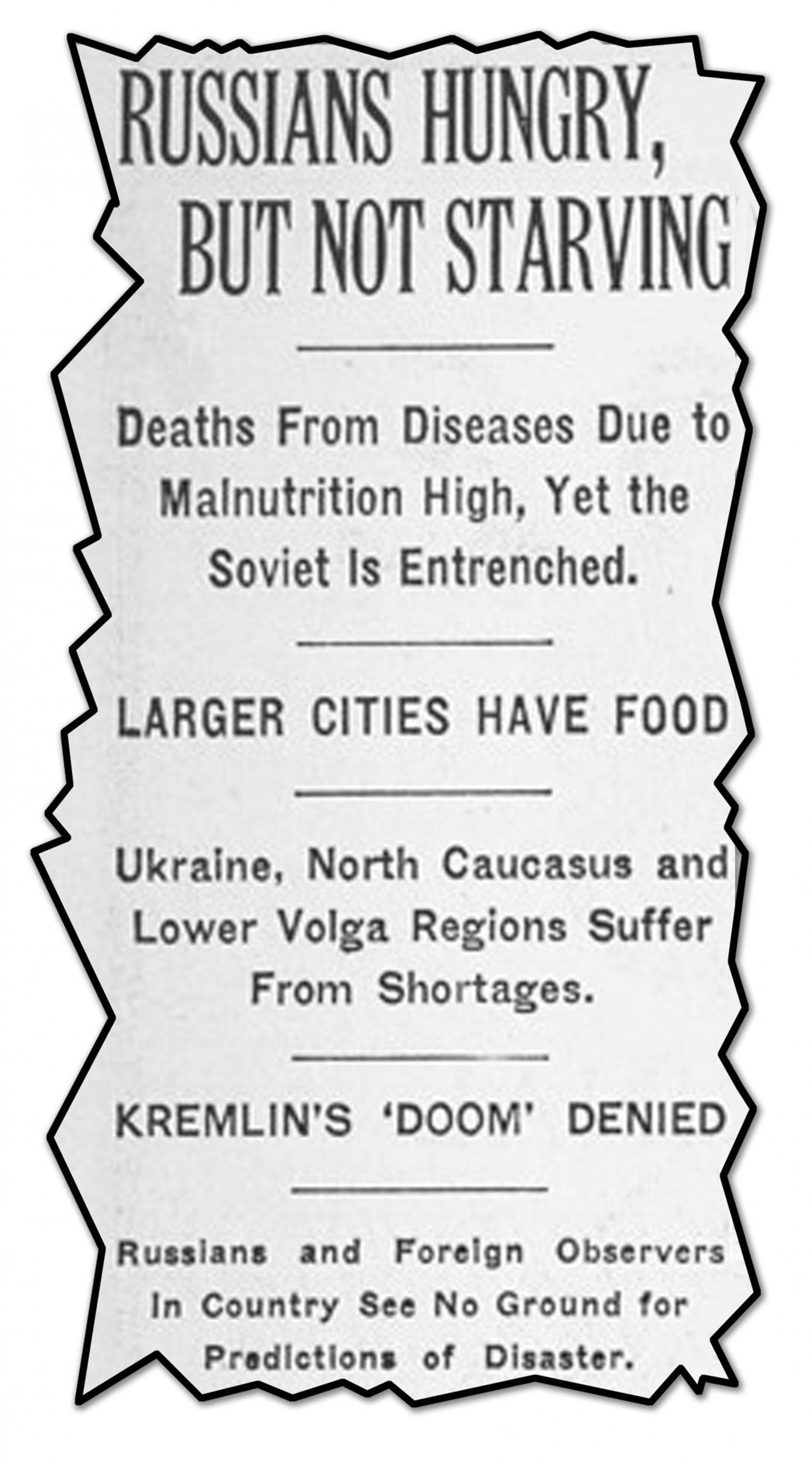

The Soviet response, led by Walter Duranty, the New York Times’ Marxist Pulitzer Prize-winning Moscow correspondent, was swift and damaging. In a 31 March article headlined RUSSIANS HUNGRY, NOT STARVING, he claimed that while it was true people were dying, disease brought on by malnutrition was the cause, not starvation. He was supported by other members of the western press corps who, despite knowing the truth, protected their positions – and their access to the show trial of six British Metro-Vickers engineers arrested for spying – by denouncing the young reporter.

In his 1937 memoir Assignment in Utopia, Eugene Lyons wrote regretfully of his own part in “throwing down” Jones, which he said was “as unpleasant a chore as fell to any of us in years of juggling facts to please dictatorial regimes – but throw him down we did, unanimously, and in almost identical formulas of equivocation.”

Orwell never went to the Soviet Union, so he relied on reports from journalists brave enough to write them in order to piece together what was happening

Jones countered Duranty’s attack with a letter published in The New York Times on 13 May 1933, in which he referred to the Moscow-based press pack as “masters of euphemism”. By then, though, it was too late. His more famous and influential adversary’s version had gained traction. Two years later, Jones was murdered. “He flew too close to the sun,” says Chalupa.

Although he met a tragically early end, Jones’s voice wasn’t lost entirely. In the film, he meets Orwell, which, as Philip Colley has said, is fiction. What it does, however, is hint at a link between the two men in regard to the transmission of truth, and the creation of Animal Farm. Chalupa explains that Orwell reviewed Assignment in Utopia, which contained a chapter called The Press Corps Conceals a Famine, and went on to write an essay, “The Freedom of the Press”, that he wanted to be the introduction to his political fable.

“He said in ‘The Freedom of the Press’, they’re going to attack this book Animal Farm, and say it’s a bad book, because they don’t agree with the politics. He recognised through Eugene Lyons and what they did to Gareth Jones, that clearly that could be done to him.

“So that was basically the connection we were making between Gareth and Orwell: Orwell never went to the Soviet Union, so he relied on reports from journalists brave enough to write them in order to piece together what was happening. It takes a chain to get the truth out, and that speaking the truth, even though Gareth was killed, was not in vain.“

Jones’s wounding by fake news in the wake of his revelations is highly relevant today. Making the truth stick has arguably become even harder because of the reach the internet affords anyone who wants to spread disinformation. Whistleblowing can obviously be dangerous, as the Jones story illustrates. In an example closer to home, Chalupa’s sister, Alexandra, found herself at risk after she became one of the first people in the US to warn officials about Russia’s attack on the 2016 election.

She started receiving alerts informing her that “state-sponsored actors” were trying to hack into her private Yahoo email account; family cars were then broken into; then a sinister woman “wearing white flowers in her hair” tried to break into her home. Talking to Politico, she said she was warned that the last of these incidents “bore some of the hallmarks of intimidation campaigns used against foreigners in Russia”.

“My sister is a mother of three kids who drives a mini van,” says Chalupa. “She simply took publicly available information and pointed it out. Anybody could have done that ... Now she has to live the rest of her life thinking that at any moment, she could be killed.

“So writing a film about a whistleblower, while seeing what my sister was being put through as a whistleblower, I can’t describe how surreal 2016 was for me, and how isolating and terrifying.”

‘Mr Jones’ opens on 7 February in cinemas across the UK

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments