The return of sport in 2021: the incredible highs and absolute lows

Sean Russell feels that in 2021, sport saved his mental health, but it wasn’t long until he was left with a nasty aftertaste, realising that there still remain the same old horrible problems as before the pandemic

In March 2020, when images of piled-up coffins in northern Italy started appearing on the news, and videos trickled through of people singing from their balconies, the last thing on my mind was sport.

How could anyone consider the temporary pausing of sporting events as the most important thing in a time when people were dying, and we still had no idea what we were dealing with? Those early weeks and months were frightening and deeply uncertain, and the Tour de France, Olympics and Euros were not what most of us were thinking about. Sport seemed, then, unimportant.

But as the old adage goes, you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone. For the next few months, I, like everyone else, stayed at home. At work I read the Covid headlines, I even wrote a few, I could not pull myself out of the news cycle. Netflix was boring, reading could only do so much, as could speaking with friends online, but nothing carried me away from this pandemic world so completely until the Tour de France in August 2020.

Then followed three weeks of complete absorption. The world’s best cyclists snaked around the mountains and plains of France, and while the roads were mostly empty of spectators, and it was strange to see the mountains bereft of its fans crowding into the roads ahead of the riders, we were transported away from our homes. What drama that Tour de France gave us as Primoz Roglic, the leader of the race, was robbed of victory on the penultimate stage by his young compatriot, Tadej Pogacar.

Life felt normal, and deaths and hospitalisations disappeared from thought, if only for a short while. Sport, it turns out, was highly important to making it through this pandemic.

But while sport returned timidly in 2020, it was 2021 when it returned to something close to normal. The cycling and Formula One calendars were more or less themselves again, the Euros were going to go ahead, as were the Olympics, fans returned to stadiums and lined the roads to watch bikes go by. Nobody was under any illusions that the pandemic would end entirely in 2021, but at least sport was back to give some release.

Formula One got quickly under way, and it soon became clear that this was going to be a vintage year. Level with Michael Schumacher on seven world titles, Lewis Hamilton had immortality in his sights but this year young Max Verstappen and Red Bull were clearly able to put up a fight against the veteran. Formula One is a sport that is often starved of season-long battles, but we all realised early on that this wouldn’t be the case in 2021. Not since 2010 has there been so much excitement for each race weekend to come around, ready for two supremely talented drivers to do battle on the track.

That Euro 2020 campaign brought the country on an emotional journey which I am nothing but grateful for, win or lose, and gave England football fans a sense of hope

Then the cycling calendar got into full swing and the racing was quickly furious; it seemed that with the year off, the riders were trying to race in different ways. After all, who knew when the season may stop due to further Covid restrictions? Whereas in a normal season riders might hold something back, targeting a particular race further into the season, this year they went full gas not knowing when they may get another chance at a win.

But it was the Euros which really gripped the whole country. I’m not a massive football fan, nor am I a patriot. To paraphrase David Mitchell, of course I’d rather England win a match over someone else, but ultimately I didn’t care, that is until I cared a great deal in the summer of 2021.

This was, simultaneously, the peak of the sporting year and the point the taste turned sour. Wrapped up in the euphoria of sport returning to normal, how many of us asked what normal meant? Euro 2020 laid bare not just the incredible highs, but the absolute lows.

What happened on 11 July 2021 need not be retold in detail here. It is probably still very clear in most people’s minds. England lined up to take penalties against Italy in the final, and three young Englishmen missed. A team who just hours earlier were held up as heroes, who took England to their first final of a major tournament since 1966, bringing the whole country along for the ride when we needed it most, became the victims of abuse. But worse, the three young black men who missed penalties received an onslaught of racist hate after weeks of the team being booed for taking the knee in a sign of unity against racism.

How could anyone do that? How could anyone be cheering these men along one minute when they’re winning and hurling abuse as soon as they lost? That Euro 2020 campaign brought the country on an emotional journey which we should be nothing but grateful for, win or lose, and it gave England football fans a sense of hope, that maybe we’re finally no longer a joke. England have a young, diverse and dedicated team who clearly enjoy playing with each other and for their country. No longer a disparate bunch of egotistical, albeit individually talented, players who’d rather be playing for their clubs. But unfortunately, it seems, football became a mirror for the country and it wasn’t a nice reflection.

I like to think that it is a minority that hurled racist abuse. I would like to believe that it doesn’t represent vast swathes of the country. And yet I cannot help but feel that while this might be the case, that fundamentally Britain is a tolerant country, something has happened which makes that minority of hateful, ugly people feel they can say what they want and shout it from the roof beams.

We can speculate on why this might be, and that maybe it has something to do with Brexit, or more specifically, the campaign surrounding Brexit which made targeting and “othering” people a “legitimate” point of politics, not a hate crime. Rhetoric about taking “our country back” and blocking immigrants and all the hideous baggage that come with such arguments seems to have seeped out and legitimised racism and other bigoted views. Sport is often reflective of a society, and football is this nation’s sport of choice. What happened during and after the Euros must have made us all question exactly where we are as a nation, and what football organisations and institutions were doing to combat this despicable hate. Following the Euros I couldn’t help but think about sport as a whole.

One of the best sporting moments of the year came from Lizzie Deignan, the British cyclist who won the first ever women’s Paris-Roubaix on 2 October. Often, cycling is so clean-looking – beautiful tarmac roads heading up into crisp mountains. The bikes are shiny and colourful and these elite athletes are sleek in their lycra. But in Paris-Roubaix we go back to basics, cyclist versus the elements; 260km, more than 50km of which are cobbles, and if it’s raining, then a whole lot of mud. The pictures of riders finishing these days look much the same as 50 years ago: muddy, exhausted faces, ready to collapse in the velodrome in the northern French industrial town of Roubaix. It is often regarded the hardest race in professional cycling. And it has taken 125 years for there to be a women’s race, running a shorter 116km route.

In 2021 there was rain at Roubaix. Deignan slipped and slid alone across the cobbles on her way to a historic victory. It was an incredible display of power and bike-handling. But there was only 60km of it to watch. The next day, all 260km of the men’s race was shown live. Likewise, it’s great that the Tour de France Femmes is returning next year, but it will feature just over a week’s worth of racing compared to the men’s three full weeks.

Sixty kilometres of Roubaix. We almost missed the attack Deignan put in to escape the other riders. While the very existence of a women’s Paris-Roubaix is a great step forward, is there really a point if it isn’t given equal billing to the men’s race? Women’s cycling offers something different to men’s; the dynamics are different, and most cycling fans only ever want to watch more cycling. Sixty kilometres is an insult and shows how far we have to go for some sort of parity. What is also an insult is the prize money awarded. The men’s winner – this year Italy’s Sonny Colbrelli – received €30,000. The women’s? A paltry €1,535, or 5 per cent of the men’s prize.

“Women’s cycling has progressed significantly in the past five years,” sports journalist and broadcaster Orla Chennaoui told me, “and it’s important to register that context. It has become significantly more professional. But race organisers still need to do more to level up prize money and facilitate more live race coverage. A women’s Tour de France is a welcome addition to the race calendar for next year, but it will not solve any deeper problems. It feels that drastic change is needed to create a more sustainable, profitable business model for women’s cycling. Simply copying the men’s model hasn’t worked so far.”

There are many debates surrounding prize money, but the truth is, there is, as Chennaoui says, a market for women’s cycling and many of the professional teams are beginning to understand this and invest, paying the same wages to the women’s teams as they do the men’s. Now the events themselves just need to catch up. But this isn’t just a cycling problem, as proven by Chelsea when they won the women’s FA Cup this year. How much did they receive? A measly £25,000. Meanwhile the men’s winners take home £1.8m.

What about the Tokyo Olympics? The two biggest stories for me were the joy of Tom Daley finally winning gold and Simone Biles having the strength to withdraw from competition on mental health grounds.

So many of us have watched Tom Daley grow up. We all remember the young man in Beijing 2008, just 14 years old, and there’s something about watching someone grow up that makes you want them to succeed. Tom Daley is everything a modern sportsperson should be: humble, kind, open, honest and talented, and watching him clinch that gold alongside Matty Lee was magic.

But while the athletes themselves for the most part were exceptional examples to us all, it is clear that attitudes around mental health still have a long, long way to go. When Simone Biles withdrew from the team gymnastics event it showed a strength beyond what she had already displayed in her incredible career so far. Mental health issues are nothing new in sport. Perhaps the pressures are higher, the training more strenuous, the coverage wider, but the lengths sportspeople push themselves to remain the same. The difference is, athletes once hid their feelings, competed when they perhaps shouldn’t, believing it better to have a bad day in the office than admit any sort of weakness.

Emma Raducanu had a similar experience when seeming to have a panic attack and withdrawing from her Wimbledon round-of-16 match. The angry old men in their armchairs took to their laptops to write about her not being cut out for elite level sport, only for Raducanu to come back and win the US Open, the first British woman to win a grand slam since 1977. This ability to be so open and honest, and still be one of the greatest athletes in the world, is empowering. It’s a “f*** you, I can be honest and kind and still come back and operate at the absolute highest level and win.”

This is a great movement away from the old and toxic mindset of sport. But while there have been some movements, some things remain the same. At the end of the year the Yorkshire cricket scandal reveals that racism pervades the institutions of almost every sport as it does every part of society.

Can we really play football and race cars in Qatar and feel OK with it? Can we really pretend racism doesn’t exist in football and cricket beyond a few fans?

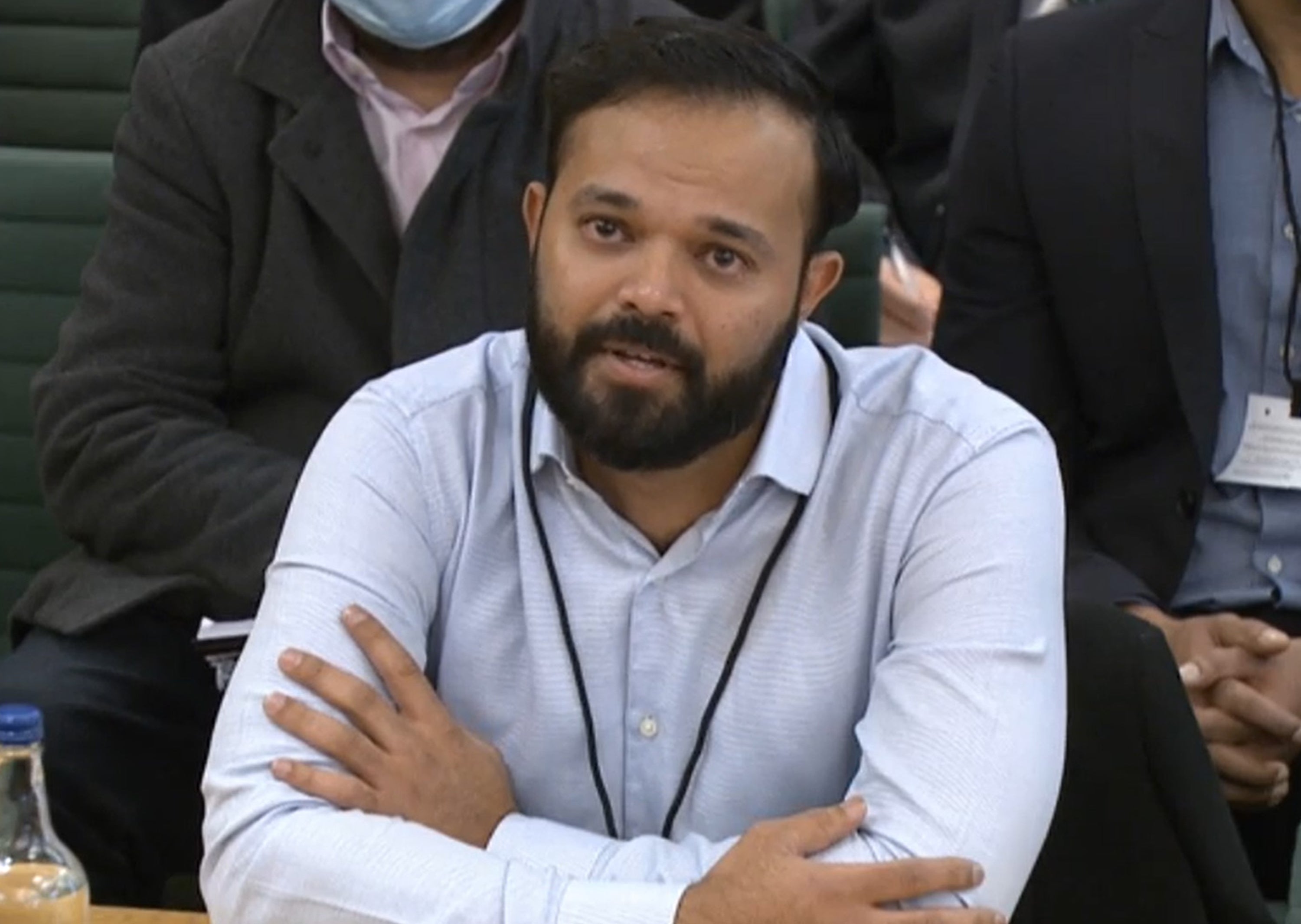

Azeem Rafiq, a former professional cricketer who spent the majority of his career at Yorkshire, claimed that “institutional racism” at Yorkshire County Cricket Club had left him close to taking his own life. An explosive claim that rocked the sport which, as Richard Edwards wrote in The Independent, is often regarded as one that embodies British values.

A formal investigation was launched into these claims and they found on 28 October that there was “insufficient evidence” that the club was “institutionally racist.” But it wasn’t enough. On 3 December the chairman of Yorkshire, Lord Kamlesh Patel, announced that they were sacking the entire coaching team.

Is cricket institutionally racist? Rafiq thinks so and his view that this is far beyond a few fans is backed by John Barnes, the former Liverpool and England midfielder.

Talking about racism in cricket and football, Barnes recently told BonusCodeBets that, “you can’t change the system from within. Anybody who’s been given a position in an institution has to protect that institution. So, when people think we need more black people in these institutions in order for things will change, they’re wrong. It won’t help.

“From a footballing perspective, people still want to point the finger at Hungarian racist football fans, or white working-class fans who throw a banana on the field, rather than at the institutions themselves. That is what he [Azeem Rafiq] knows they’re trying to do in cricket. But that’s what we, in football, are saying we need to do.”

As we head into another uncertain year, fear has begun to set in again, that perhaps normality is further away than we thought. But even amid the early feelings of anxiousness, on 12 December, sport came to the rescue again.

Hamilton vs Verstappen, the final race of the season in Abu Dhabi, level on points after 21 races, winner takes all. For two hours, millions of us were glued to our screens, completely absorbed in the drama and the tension, and just when we though Hamilton had won it, it was snatched away on the last lap. It felt like we were watching one of the historic moments of sport, something we’ll talk about for years, and while the end was controversial – and we all certainly have our opinions on the matter – it was once again proof of how sport was so important at taking us away even just for a little while.

But that sour taste couldn’t be shaken. It’s hard to stomach that a sport which uses the new motto “we race as one”, as a way to suggest it is making strides on equality and diversity, then goes and races in countries such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

Lewis Hamilton, time and time again, stands up and says what he thinks. He has been a vocal proponent against racism in the sport and society and he supports many causes including fighting climate change and supporting animal rights. In Saudi Arabia he and Sebastian Vettel wore helmets with the rainbow colours to show their support for LGTB+ people while highlighting the views of and human rights abuses of those countries. Yet the sport itself does very little, in fact it seems to embrace these places and legitimise them.

And it’s not just Formula One that’s guilty of “sportswashing”. Next year the Fifa World Cup is set to take place in Qatar, and the Winter Olympics will be in China. Yes, the US and UK among others can launch a diplomatic boycott of the Olympics, citing human rights abuses and the genocide of Uyghur Muslims, and the strange disappearance and questionable reappearance of Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai, but what does that really mean? Short of a full boycott of athletes how many people care if the diplomats aren’t there?

The question remains: what needs to happen for sport, and the institutions and businesses that support it, to fall in line with a changing society? In most cases, the athletes themselves are there. Hamilton is often an incredible role model, for example, as are Raheem Sterling, Marcus Rashford, Raducanu, Biles and many many others. These are a new generation of athletes who seem genuinely good people, while also competing at the absolute highest level – possibly the highest levels ever seen – and taking their sports in better directions. And still the institutions that support them seem so hopeless in keeping up.

Can we really play football and race cars in Qatar and feel OK with it? Can we really pretend racism doesn’t exist in football and cricket beyond a few fans? Can we really act as if women deserve to be paid so much less than men at the elite level? Can we really keep applying pressure to these young people and expect them not to break? Elite-level sport is hard, and it should be hard, but not to the detriment of a person’s life or another’s rights.

Sport saved my 2021, as I’m sure it saved millions of people’s, and I cannot wait for it to come back next year. I hope to get out to Italy to watch the Giro d’Italia and to France for Paris-Roubaix. I want to be at Monza and Silverstone again, and this importance and reliance has been laid bare for me this year. Sport can take you away from it all just for a few hours, it can distract you, it can inspire you, it can bring people together, it can make you feel less alone. But as we move forward – and we are going in the right direction – we have to ask what sport should look like in the future and whether or not we are happy with it as it is.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments