A modern medium for the oldest form of storytelling

Podcasting has been around since the 1980s, but thanks to the launch of true crime series ‘Serial’ five years ago, it’s an industry that could be worth $1bn by 2021. Harriet Marsden speaks to the creators about how the show not only triggered a renewed interest in the medium, but a renaissance in investigative journalism

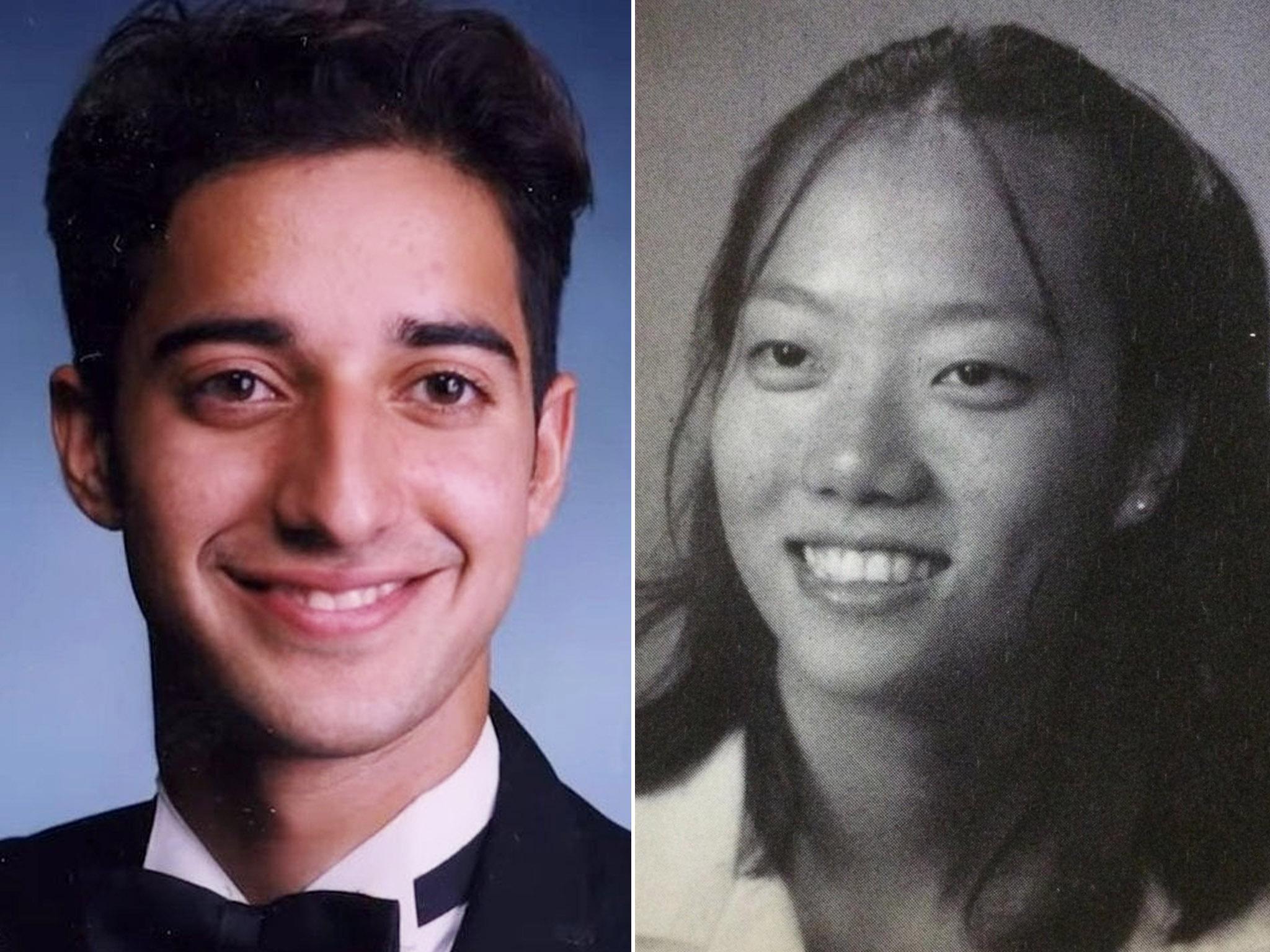

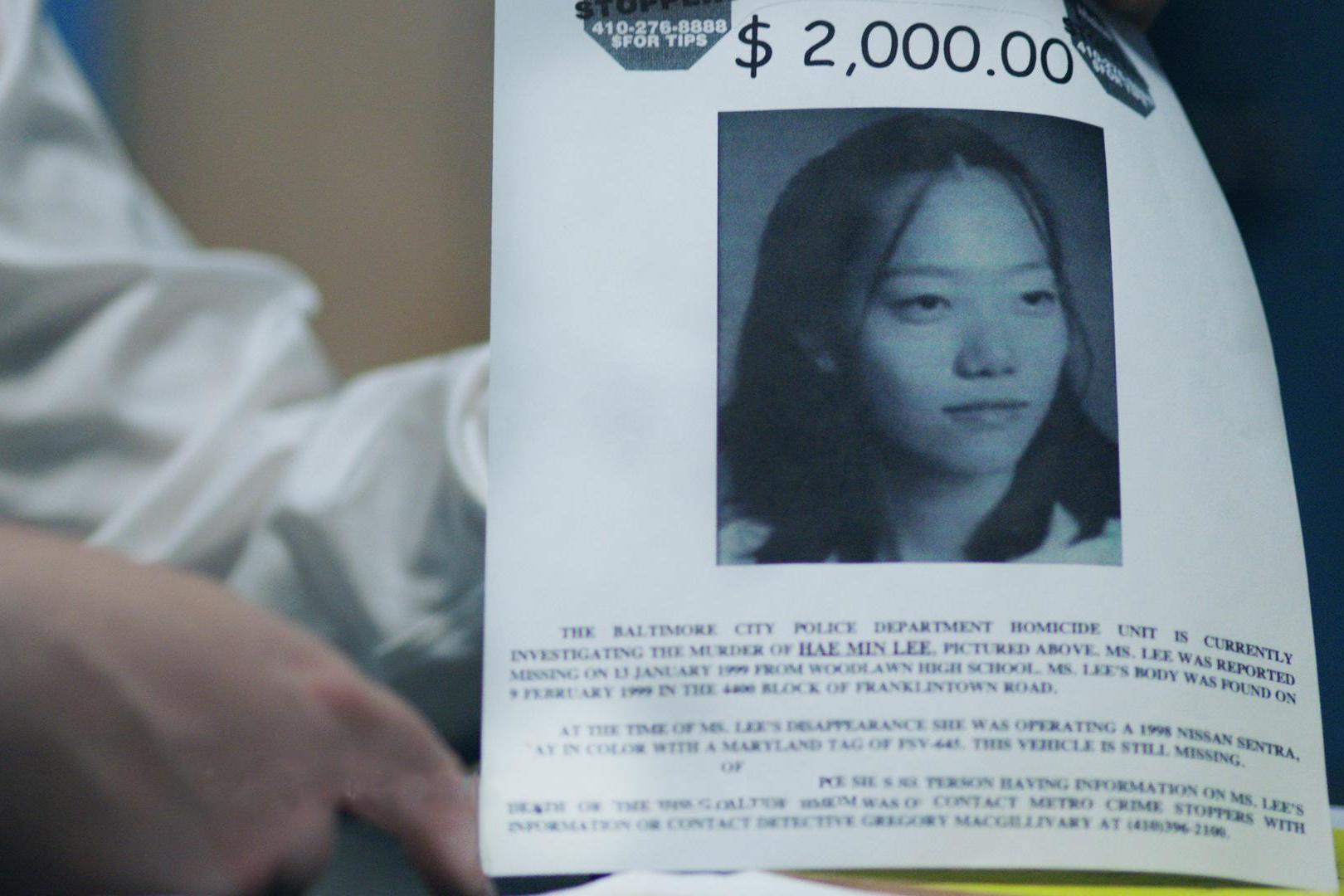

Hae Min Lee was a typical high school student in Baltimore 1999. A popular Korean American girl, she was bright, pretty, romantic. On 13 January 1999, she was last seen driving from school to pick up her younger cousin. When she failed to turn up, her parents reported her missing. Police concluded that by that time, she was already dead.

A few weeks later, a known streaker was walking in Leakin Park, west Baltimore, to find somewhere to urinate. Instead, he stumbled on a partially buried body. Hae was found to have died by manual strangulation – hands around her neck. The trail, consisting of later-disputed cellphone tower signals, one singularly unreliable witness, 21 crucial minutes without an alibi and entries in Hae’s own diary, would lead police to her ex-boyfriend: Adnan Syed. The Muslim son of Pakistani immigrants in a majority-black high school, he was athletic, charismatic and hard-working. But despite the lack of definitive physical evidence and, it was later claimed, a negligent defence attorney, Syed was convicted to life imprisonment for first-degree murder. He is still in prison today.

This story might be a canvas of Shakespearean tragedy: young love, cultural divides, family secrets, betrayal, murder, but it was still one case, in one city with an infamously high murder rate. It’s unlikely that it would have received international attention, much less captivated millions around the world some 15 years later. But Hae’s case – or rather, the case against Syed, and where the prosecution might have gone wrong – became the subject of the record-breaking podcast Serial, which debuted five years ago today.

The radio programme This American Life developed the first season of Serial (“One story told week by week”), but it was created and produced by Sarah Koenig (the narrator) and Julie Snyder. It is now seen as the crucible of the podcast revolution. It was called the medium’s first big hit, bringing podcasting out from the niche into the pseudoviral sphere. It broke all downloading records, triggered a massive interest in the medium of podcasting and a renaissance in true crime and investigative journalism. It led to a four-part HBO documentary, a bid for a retrial (later denied), and was even the first podcast to win the prestigious Peabody Award. At last count, the first season was downloaded more than 175 million times, paving the way for two subsequent seasons and a spinoff, S-Town.

But unlike almost all comparable dramas, it made no conclusion. Koenig’s final judgment on whether Syed was guilty? I don’t know. But instead of frustrating the audience, it ignited them.

Five years later, Koenig tells The Independent that she and Snyder were “shocked” at the response to the first season of Serial. “We had no idea what was going on. With some distance, we have a little more perspective on it, but at the time it was bonkers. We had no idea what was going on. People really love a murder mystery, and I hadn’t understood that going in.”

Koenig, however, modestly points out how lucky they were with the timing. “The new iPhone came with that podcast app built in, so it became much easier to find podcasts and listen to them; you didn’t have to do the weird syncing and plugging it into your phone. That happened right before we launched. I think that was a huge reason that it caught on the way it did.” Like Impressionism, which took off with the invention of painting tubes that could be taken outside, so too was the success of podcasting dependent on new, cheap, more mobile recording and playback devices.

Koenig wasn’t working in podcasting, but as a producer for This American Life, hosted by Ira Glass. A couple of years before she began working on Syed’s case, Snyder had suggested to her that they start their own radio show. They settled on an idea – “a little bit the opposite of what Serial became” – before Glass, who would be funding, asked them whether they had anything else they were interested in.

“And I kind of just quickly blurted out, what if we came back to the same story every week? And you’re sort of figuring out with the audience in real time? And so suddenly we had this completely new idea, which was just basically a serialised documentary that was going to be a radio show.”

Koenig wasn’t particularly interested in podcasts at the time – although there were some popular examples around by then, including Marc Maron’s WTF, there were no narrative podcasts to speak of. “And I like a story. I like to be told a story. So we had no model.”

Podcasting as a medium has its roots in 1980s audioblogging, long before the internet, much less Web 2.0. RCS (Radio Computing Services) allowed music and audio files to be downloaded digitally: in essence, it was radio that could be paused or played at will. It took off in the early Noughties, fuelled by an explosion in MP3 devices and iPods, cheaper recording equipment and the power of webbloggers to curate taste and trends online. The journalist Ben Hammersley, writing for The Guardian in 2004, coined the phrase “podcasting” (taken from the word iPod) to describe the downloading and synchronisation method of consuming audio content.

But it was still relatively niche, demanding a good deal of committed effort. Most now credit the first season of Serial with introducing podcasts to a wider mainstream audience, and almost all hosts of subsequent true crime investigations cite Koenig as an influence.

It’s one of the only pieces of content or media that can be consumed while multitasking, while doing a thousand other things. You can’t read a book while you’re walking up and down the grocery store; you can’t watch a YouTube video while you drive. You can’t do any of those things while you’re doing laundry

She had been introduced to Syed’s case by Rabia Chaudry, an attorney and friend of the family who had come across Koenig’s reporting work in The Baltimore Sun on Syed’s defence attorney, Christina Guttierez. Chaudry claimed that Guttierez had “thrown” Syed’s case. She, and the vast majority of her colleagues, were convinced of Syed’s innocence. You hear snippets of this conversation in the first episode of Serial, which also gives you a sense of its appeal: the personal tone, the informal language, and the discovery of information seemingly alongside the host.

A good deal of Serial’s appeal also lies in the long phone conversations with the Maryland correctional facility: Koenig spent many hours speaking directly with Syed, and to hear his verbatim response to accusations and newly uncovered bits of evidence is either deeply moving and unsettling, depending on whether you believe him to be guilty.

Hae’s voice is set, unchanging, in her diary entries read by Koenig, but Syed the adult becomes a central character to be considered alongside the memory of Syed the teenager. But what set Serial apart was the inclusion of the audience in the investigative process. Koenig, and occasionally Snyder or producer Dana Chivvis, test the state’s case against Syed: driving through school parking lots to test timings, walking through the woods, examining the cell towers, and what they discover along the way brings the story into the present day for the audience, when in reality the story died in 1999.

The group had initially planned to produce Syed’s story as a radio show, but about six months in, Snyder suggested changing it to a podcast – because it would be cheaper. Koenig recalls her saying: “You don’t have to sell it, and if it sucks no one will hear it.”

A pragmatic decision, but a wily one. Some might question the difference between a radio show and podcast. The answer tends to be in the consumption: on-demand, in your ears and with binge potential. Jon Manel, the award-winning investigative journalist who was made the BBC’s first dedicated podcast editor in 2017, explains that radio provides the “background soundscape” to his mornings, with one on in every room in the house all tuned to different morning news programmes. “Podcasting tends to be a much more intimate affair. Like many, I listen to podcasts on my own with headphones. The tone of most podcasts is particularly suited to that way of listening. With my favourite podcasts, it sometimes feels like the host is only talking to me, even though hundreds of thousands of others will have downloaded it too.”

He explains that podcasts are perfectly suited for investigative journalism because they are not constrained by time, and so the story can develop over as many episodes as it’s worth. “Imagine an audience of the size which the first season of Serial attracted sitting down to read a story told that much detail in a newspaper or magazine article. Podcasts do seem to be attracting a new audience to investigative journalism. And episodic storytelling is developing and becoming more innovative, so those listener numbers will hopefully continue to grow.”

Which is precisely the aim of organisations like the Podcast Brunch Club, set up by Adela Mizrachi in 2015, who was working at Northwestern University in Chicago as a communications specialist at the time. It’s a forum where people can synchronise which podcasts they’re listening to and discuss them together, and now boasts almost 70 chapters on six continents.

Podcasting tends to be a much more intimate affair. Like many, I listen to podcasts on my own with headphones. The tone of most podcasts is particularly suited to that way of listening. With my favourite podcasts, it sometimes feels like the host is only talking to me, even though hundreds of thousands of others will have downloaded it too.

On the surprise global success of her club, Mizrachi tells The Independent that podcasts lend themselves well to today’s modern lifestyle. “It’s one of the only pieces of content or media that can be consumed while multitasking, while doing a thousand other things. You can’t read a book while you’re walking up and down the grocery store; you can’t watch a YouTube video while you drive. You can’t do any of those things while you’re doing laundry.

“What sets podcasts apart from radio is the fact that it’s right on this computer that we’re carrying in our pockets everywhere. Podcasts are on-demand in a way that radio is not. Podcasts disrupted radio channel surfing the way Netflix did for television. And Serial started it all, right?” Mizrachi launched her club just a few months after Serial finished. “I think it was the mystery of all of it: it started a whole true crime craze, and now it feels like every other podcast is true crime.”

Koenig is hesitant to accept the true crime categorisation for Serial. “I didn’t even really know the genre of true crime; it never occurred to me that that’s what we were doing. I’m not interested in true crime, and I don’t consider myself to be someone who’s doing that. But people responded to it as true crime.”

Mizrachi puts it bluntly: “She can want whatever she can want, but she only has limited control over what it becomes. The listener community is what makes it what it is: a global phenomenon of a true crime podcast.”

Koenig is definitive, almost rueful, on how the show took on a life of its own. “People interacted with the story as entertainment in a way that we did by design, but we didn’t want to the degree that it happened. We didn’t realise the monster we were creating by doing that.”

She stresses that a lot of the response was “wonderful, exciting, gratifying” – but that there was a “big chunk of it that was also very upsetting to me and everybody who worked on the show. People were treating this real story about a real young woman who died, and possibly a person who was serving a life sentence for something he didn’t do – these were real people with very high stake situations – like it was fiction, and felt free to armchair detective, sleuth it, and hound the people on Reddit.

“We didn’t expect anybody to get harassed or accused of things like on Facebook, on hunches people have when they were sitting at home. All that started to happen online and that was very upsetting.”

But audience participation – so much rarer in other media – can also prove to be a podcast’s strongest USP. Take Death in Ice Valley, a BBC World Service podcast commissioned by Manel, which was released in 2018. In this case, it’s not as clear whether there is even a crime to solve: the podcast tells the story of the mysterious Isdal Woman. Her badly burnt body was found in the remote Ice Valley near Bergen in Norway in 1970, with the labels cut off her clothes and traces of barbiturates in her system. Police discovered multiple identities for her, as well as disguises and coded messages. Was she a spy? Was she a suicide case? Was she a murder victim? Was she a lunatic? The case remains unsolved – despite the best efforts of Marit Higraff, a Norwegian journalist for NRK, a Norwegian broadcaster, and co-presenter of the podcast.

My favourite thing about podcasts is that they fill in half of it and you fill in the other half, so there’s this imaginative engagement that’s similar to books. In a podcast, you construct the images. I think in a certain way it’s kind of the most imaginatively engaging medium

Higraff had been working as an investigative TV journalist for a long time on the strange cold case of the Isdal woman – but, she tells The Independent, she didn’t want to just retell a true crime story: she wanted to solve it with investigative journalism and modern science. She made the project in Norwegian, which was picked up by a BBC journalist, and it became one of the most successful stories on the world service, which is where Manel read it. He contacted Higraff to ask for a meeting. Cooperation between two international broadcasters is rare, says Higraff, so they were interested. And of course, she says, she looked to Serial for guidance. But the audience involvement was the BBC’s idea: they wanted to have a community on Facebook of listeners to participate.

The Facebook group became a behemoth, with nearly 25,000 active members sharing theories and clues, translating between Norwegian and English and, crucially, interacting directly with Higraff and her BBC co-host Neil McCarthy. The hosts would either reply on the Facebook group or address theories directly in podcast episodes, creating a multimedia experience for listeners. “In the beginning, it frightened me totally,” laughs Higraff. “I thought one morning I’m going to wake up and they’ll have solved this case.”

Like Koenig, podcasting was completely new to her, but now she believes it was an excellent way of bringing the story and investigation to an audience – in particular, an international one. “It lends itself well to this kind of story,” she says.

“I can still see every day, every week that it reaches new countries and new listeners. Normally you produce your show, report or interview, and it’s broadcast, and the next day it’s forgotten. And podcasts are so different to that. It’s something people can listen to whenever it suits them.”

As Manel puts it, “Sometimes podcasts which don’t have a definitive outcome can be frustrating, but Death in Ice Valley is different – it makes a virtue of the fact that it’s an ongoing investigation. And as the answers are almost certainly going to come from outside Norway (where the story starts), there’s a very good chance that information from our global audience could help solve the investigation.

“There are still thousands of new downloads of Death in Ice Valley every day and the Facebook group continues to grow. The latest episode, recorded in front of an audience in Bergen, was based entirely on the work of our listeners. At its heart is a real story of a woman who died in terrible circumstances and l think people around the world really want to help find out who she is, so her family can be contacted.”

This global, cross-border potential of podcasts is something that became evident with another hit in 2018: Caliphate. Like Serial, it would go on to win the Peabody, and it made the host, New York Times reporter Rukmini Callimachi, a 2019 Pulitzer Prize finalist. Unlike Serial, or indeed Death in Ice Valley, there was no obvious crime to solve at first. But like both, there was death at the heart.

Caliphate describes the ongoing US fight against terrorism, and features Callimachi expanding on her beat as an experienced terrorist reporter, from covering west Africa as an AP bureau chief when “al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb” took over the north half of Mali, to interviewing Isis members fleeing the fall of the territorial caliphate. At the heart of the podcast is her long night of interviews with a young man from Canada who claims to have returned from Isis, calling himself Abu Huzaifa. He describes to Callimachi leaving his native Canada for Syria, joining Isis and fighting for them for two years before becoming disillusioned and coming back to Canada. In the podcast, he admitted to two murders. He was still free when he gave his interview. Callimachi had found him on an Instagram group.

Callimachi tells The Independent that the extent of the podcast’s reach surprised her. “There were real experts that wrote to us. People like Jacob Zenn, the premier expert on Boko Haram, said he reads the literature on recruitment and radicalisation back to front, but that the podcast explained better than anything he’d come across how this had actually happened.

“We learnt that Tajik authorities had been listening to the podcast, and Turkish intelligence, listening to it in order to try and understand. So I felt like the public service aspect that we were trying for had actually happened.”

At last count, Caliphate had been downloaded 25 million times – even though iTunes refused to list it, because The New York Times gave subscribers an episode one week before the public. Callimachi says: “I think if we had been on ITunes it would have been many multiples of that.” And although her colleagues struggled to sell adverts before the podcast was launched, the few companies that did buy ads did very well out of it.

Of course, Callimachi is a self-described “huge, huge” fan of Serial. “I was still living in Senegal when it came out, and wifi speeds weren’t great back then, so I remember downloading these episodes, putting it on my phone and listening to it in the bathtub. I think I listened to it maybe three, four times. Do you remember that episode with the public telephone? You felt like you were a detective alongside them.

“A lot of true crime podcasts that I’ve listened to since have kind of grated on me, because I feel like they’re trying to recreate Serial. But Serial sucks you in: you can’t stop listening to it.”

She also notes how podcasts help develop an intimacy with the host as a person, as well as a reporter, which sets it apart from many journalistic media. “I used to listen to This American Life religiously, and I met Ira Glass in a yoga class in Chicago when he was upside down in sirsasana. I heard his voice, and I was like, why is that man’s voice so familiar? It sort of felt like I had met Barbra Streisand, or something.”

Galen Beebe, one of the editors of Bello Collective, a publication dedicated to podcasts, laments that despite the demonstrable global reach and massive profit potential, podcasting is still misconceived as a niche art form – although, she says, Sarah Larsen getting her critic column in The New Yorker was “a big moment” for podcast journalism.

Beebe’s podcast journey also began with Ira Glass’s voice, when he came to speak at her college in 2010. But she too calls Serial “revolutionary”, explaining that she listened to each episode twice in a row.

“My favourite thing about podcasts is that they fill in half of it and you fill in the other half, so there’s this imaginative engagement that’s similar to books. In a podcast, you construct the images. I think in a certain way it’s kind of the most imaginatively engaging medium.

Podcasting as an industry might now be worth a fortune: estimates say it could scrape $1bn by 2021. It has exploded as a new medium only in the past five years, but at its heart it’s the oldest form of communication: oral storytelling. And in a certain way, the third and most recent season of Serial, which debuted a year ago, feels like the natural culmination of season one, two and all the true crime podcasts that it inspired. The final season takes a step back from outlier cases, and aims to tackle the justice system as a whole, by examining how all crimes are prosecuted in one courtroom in Cleveland.

But Koenig says that even now, five years later, she’ll be talking about something else – season three, perhaps – and inevitably someone will come up and ask her about Syed in season one, and “what she really thinks” about his guilt or innocence. “And I’m like, you think if I knew what happened I wouldn’t have told you guys? That’s crazy!”

To this day, what really happened to Hae Min Lee is tragically uncertain. But what is certain is Serial’s cultural impact. Koening says: “Journalism changes policy, that’s why we do it. You hope powerful people are listening and paying attention, and public pressure comes to bear, and something changes. So I knew it writ large, I hope it writ large, that journalism can have an effect.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks