Secrets of the Viking Stone: Is everything we know about the birth of America wrong?

Didn’t Christopher Columbus discover America? A Viking Runestone suggests not – or is it just another hoax? James Rampton investigates

As they drive into the town of Alexandria, Minnesota, visitors are greeted by a most unusual figure standing by the roadside. Big Ole is a 28ft tall, four-ton model Viking, sporting a jaunty winged silver helmet, a voluminous ginger beard, a yellow tunic and a flowing red cloak. In one hand he is holding a fearsome spear, and in the other a shield emblazoned with the words: “Alexandria, Birthplace of America.”

Wait a minute, wasn’t America discovered by Christopher Columbus, not Big Ole? Not necessarily. A new investigation reveals that America might in fact have been reached first by Viking explorers, centuries before Columbus, and central to this thesis is the Kensington Runestone.

This astounding artefact – which was unearthed in Kensington, Minnesota, and is now on display at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria 20 miles away – may overturn the previously accepted doctrine of discovery and compel us to rewrite the history of the US. This is a potentially seismic story which shows everything we thought we knew about the birth of America might be wrong. So, do we have to consign Columbus to the dustbin of history? To answer that we have to go back to where it all began.

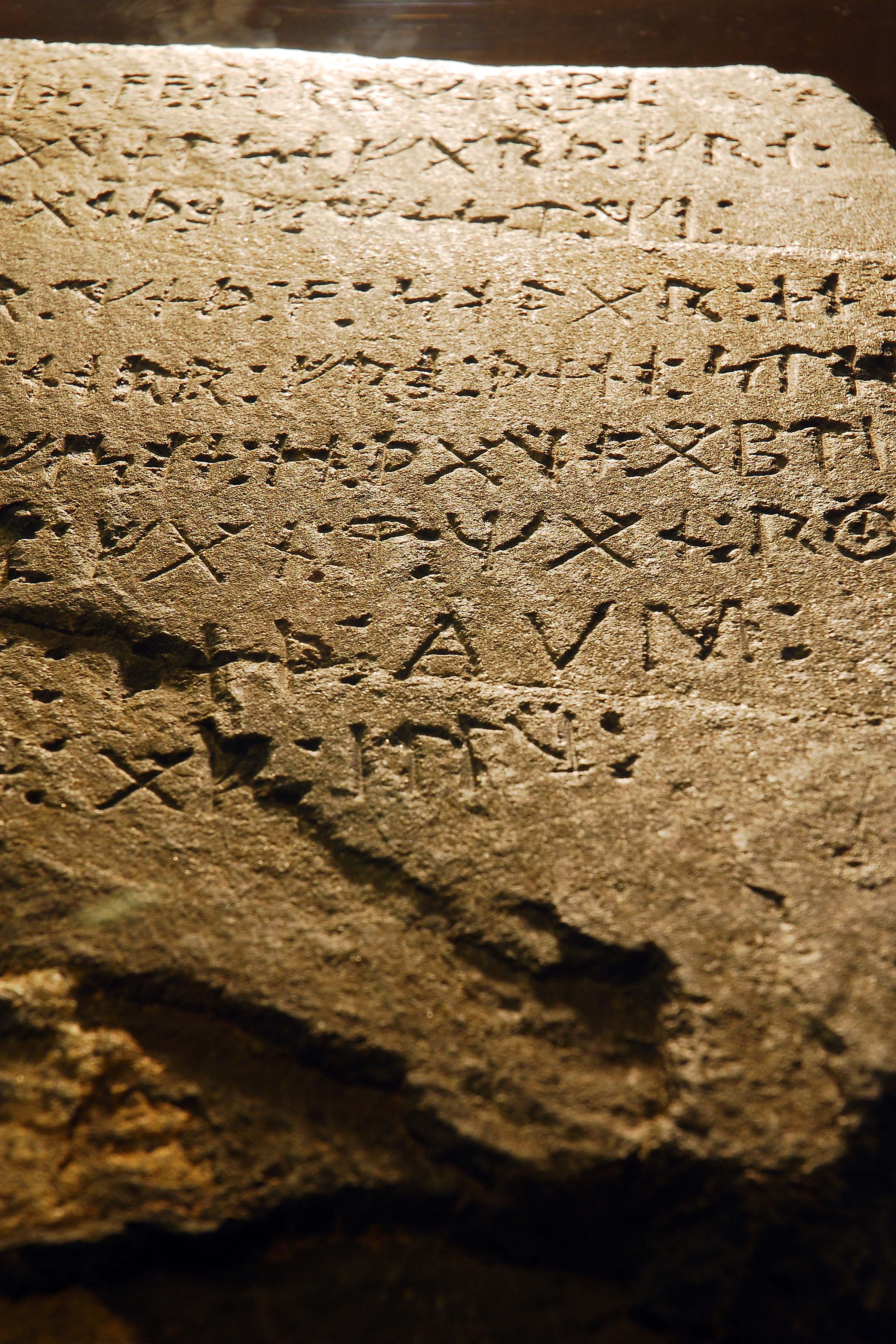

In 1898, the Swedish-born farmer Olof Ohman announced to the world that he had found a 90kg greywacke stone adorned with runes. It was buried under the roots of a tree on some land he was clearing in Kensington. Before you could say “epoch-making discovery”, it became known as the Kensington Runestone.

The stone’s markings were identified as Scandinavian runic writing, which scholars translated as: “We are eight Goths and 22 Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vinland to the West. We had a camp by a lake with two skerries [small rocky islands] one day’s journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home, we found 10 of our men red with blood and dead. AVM [Ave Virgo Maria, or Hail, Virgin Mary], save us from evil. Year 1362.”

The discovery, which indicated that the Vikings landed in America 120 years before Columbus, soon became an international sensation. It provoked worldwide attention, quickly followed by scepticism, and then anger. Ohman and his family were vilified and accused of trying to defraud the public – and, worse still, trash the foundation myth of America. Since then, experts have argued furiously over the authenticity of the stone. It has become one of the most controversial artefacts in history.

I had a vision of his wife standing beside me in the museum dressed in black. She was looking at me and saying, ‘You have to clear our family’s name’

For the last quarter of a century, actor Peter Stormare has been riveted by the story of his fellow Swede. His interest was first piqued when he was starring in the Coen Brothers’ wonderfully unconventional, Oscar-winning film, Fargo, which was filmed near Alexandria. To underline his fascination, the actor – a Coen Brothers favourite who also appeared in The Big Lebowski – is now presenting Secrets of the Viking Stone, an intriguing, peripatetic six-part Sky History documentary.

Accompanied by a local history expert with a name straight out of a Coen Brothers movie – Elroy Balgaard – Stormare drives around rural Minnesota past places such as Viking Speedway and Viking Plaza and samples the local Runestone Man beer. His mission? To try to establish the validity of the artefact.

Is the Kensington Runestone authentic, or did Ohman perpetrate a hoax as daring as The Hitler Diaries? Is the history that every American child is taught in elementary school erroneous?

Talking to The Independent from his home in Los Angeles, Stormare is an engaging presence. Like the film for which he is best known, he makes for quirkily entertaining company. Dressed in a plaid shirt and a baseball cap, the 67-year-old starts by revealing that he was inspired to make this documentary by a very unlikely character.

He recalls that when he visited the Runestone Museum while scouting for movie locations in the area last year, he was staring intently at a photo of Ohman when he suddenly saw that they looked the same. Not only that but he realised that Ohman was from a village in Halsingland in Sweden that was very close to his own, just 15 minutes’ drive across the forest; Stormare had even played football against his village.

“He looked like me. He had the same kind of eyes and nose,” says Stormare. “I thought, ‘Jesus, we were born a 100 years apart, but we have so many similarities. For a start, we both moved to America. Destiny brought us together in Kensington, Minnesota, of all places!”

At that point, Stormare’s visit became even more surreal. “All of a sudden, I had a vision of his wife standing beside me in the museum dressed all in black. She was looking at me and saying, ‘You have to clear our family's name’, and I thought, ‘Olof was ridiculed and accused of forgery and in the end he didn’t want to have anything to do with the stone. I have to start digging into what really happened to this man’.”

Stormare, who is married to his wife Toshimi and has one daughter, lays out what he hopes to achieve with the documentary: “The Ohman family homestead became a circus. Olof and his wife really hated it when people came down to look at them. They became a sort of freak show. There were two suicides within the family because of the pressure, and Olof said to one of his sons, ‘I wish I'd never found this stone.’

“Despite a lack of evidence, Olof was declared guilty in the court of public opinion. He was the easiest person to blame, but I believe he was innocent.”

During the course of Secrets of the Viking Stone, Stormare, who claims to have inherited psychic gifts from his mother and seen visions of many people (“but unfortunately, not John Lennon!”), uncovers a wealth of evidence that the Kensington Runestone is genuine. “It’s obvious today that the Vikings were in America,” he contends.

“Other Viking stones and artefacts have been found on the East Coast, from Newfoundland down to Maine and Martha’s Vineyard. So if you come all the way across the Atlantic to Newfoundland and Maine, it is not hard then to go on to the lakes and middle America. Compared to the voyage the Vikings made to the Middle East, that’s a pretty easy journey.”

So why have scholars down the generations been so quick to charge Ohman with manufacturing an elaborate fake? Perhaps because they were anxious to protect the myth

Stormare also disinters considerable geological evidence pointing to the fact that the Kensington Runestone is more than 600 years old. For instance, Scott Wolter, a forensic geologist, concludes that the weathering of the stone is consistent with it dating from 1362. He asserts: “I trust rocks. I don’t always trust people, but rocks have never lied to me. They don’t have egos. They don't care.”

So why have scholars down the generations been so quick to charge Ohman with manufacturing an elaborate fake? Perhaps because they were anxious to protect the myth of exceptionalism predicated on the Columbus foundation story.

Balgaard, who accompanies Stormare on his quest, admits “it’s a little scary. Sometimes when you rewrite history, it doesn’t make everybody happy. But I’m excited about coming in and upsetting the apple cart!”

In Wolter’s view: “The geology has proven that the Runestone is authentic. To academics, this is forbidden. There is a status quo here, and you’re not going to step out of the status quo.”

It is true that if the Runestone is real, then that information may be too hot to handle for many. Alice Beck Kehoe, a doctor of anthropology from Harvard, says the belief that the Runestone may be genuine presents, “an open challenge both of the mythology of America and to actual politics”.

That mythology has been enshrined since 1493, when the Pope gave the King of Spain permission to take over new-found territory in America and force its inhabitants to become Christian. The invaders were, according to the Pope, simply obeying God’s command. This idea that you are enacting the will of God by conquering America begins to unravel, though, if you admit that someone else got there first. Matthew Northrup, professor of Native American history, asks: “How can you discover something that was already there and inhabited by other people?”

Kehoe agrees, wondering, “what are you going to do when you find that centuries before your troops got there, another Christian nation had found this place? And what are you going to do when your whole story is based on manifest destiny? You can’t deny that because then you’re denying God.”

The world may well have turned out very differently if the Vikings had chosen to settle in America. Stormare, who in Fargo played Gaear Grimsrud, the silent, sociopathic, bleach-blonde killer who famously disposes of one victim in a wood chipper, reflects: “The Spaniards and the Portuguese came here with a letter from the Pope saying that if the people already here would not turn themselves over to God and kneel before the Bible, they could be butchered and their land could be taken.

“So when Columbus came, it led to the slaughter of an estimated 11 million Native Americans. That was something that should never have happened, and the world would have been a better place if it hadn’t. But we can’t rewrite that part of history.”

Like its presenter, Secrets of the Viking Stone is eccentric, funny and unorthodox. In one sequence, for example, Stormare and Balgaard bicker like an old married couple as they debate whether to overtake a car going one mile an hour below the speed limit.

Documentaries have become a little bit boring. There are too many about Jack the Ripper – how many hours on Jack the Ripper do we need?

When Stormare finally decides to pass the offending car, he urges Balgaard to give the other driver the finger, but his passenger firmly refuses, declaring, “I don’t do that sort of thing.”

The presenter expands on why he prefers his documentaries to be offbeat. “I love documentaries. I always watch them when I’m exercising on my stationary bike. But documentaries sometimes point the finger and tell you what to think too much.”

With Secrets of the Viking Stone, “I wanted to do a documentary where the viewer is discovering things as we go along. That’s why it’s more like a road movie. People feel like they’re in the car with us, as we take a little turn to the left and then a little turn to the right. Documentaries have become a little bit boring. There are too many about Jack the Ripper – how many hours on Jack the Ripper do we need? And a lot of Second World War documentaries are just ‘pow pow bang bang.’ They are like action movies with all those sound effects.”

Which is why Stormare wants to slow the pace down, so everybody can be drawn into the documentary. He wants the viewer to feel part of the journey with two regular human beings discovering things along the way.

In spite of his desire not to be didactic, Stormare still believes we can learn from history: “History can teach the generations to come. The more we open the windows and doors in our soul and our brain, the better.”

This is especially true in the midst of the catastrophe currently gripping the world. “A lot of people today are complaining that we’re going through the pandemic. And I just say, ‘use this year to honour your ancestors’ because they went through wars, famines, the Spanish flu, and other shit. But they survived. And they fought very hard to survive. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be sitting here today, and you and I wouldn’t be having this conversation. They had remarkable tenacity and resilience.”

Sometimes, the actor says, he feels like many people believe the world was just made for them and their generation so it’s fine to take and eat everything. But he believes that’s just not true, that we’re only here for a little while and we need to pass it on to the next generation, so we should teach them to spread the light.

How can we achieve that? “By showing that after all the atrocities and all the wars that have happened, we finally found some kind of peace. After the Black Death that went through Europe in the 14th century, the Renaissance came and modern medicine and art started to develop. Hopefully something similar will come out of this pandemic.

“People have been doing horrible things to each other forever, but we can have peace. Just have some respect for the people who have gone before us on this earth. Be a carrier of the torch that brings light.”

A man with many strings to his guitar, Stormare has been using the lockdown profitably, recording new music with his band, the felicitously named Blonde from Fargo. But the group are not striving to emulate his fellow Swedes and become the next ABBA. “I don't need a hit single,” says Stormare. “That’s not why I'm doing it. I’m doing it for my soul. There’s nothing like music to heal your soul. Also, the closest we’ll ever come to a time machine is music.”

We cannot part without a final question. Twenty-five years since its release, why is Fargo still such an iconic movie? “It’s a simple story that a lot of people can relate to,” Stormare says. “It doesn't have a boom-crash-bang approach, and it doesn’t need a big John Williams soundtrack. It’s slow paced. I call it The Flying Dutchman of movies. It slowly comes and goes right through your brain. If you sit and watch it, something creeps into your soul and you can’t really put your finger on what it is.

Read More:

“It’s just regular people in weird situations. We have all been in weird situations. It's very understandable. I know people like action movies and James Bond and all that, but it's also good to have alternatives to those kinds of paint-by-numbers films. It’s positive to offer something different and unpredictable because we all know James Bond is never going to die.”

Unless, of course, 007 happens to visit Fargo and bump into a brooding, unnervingly taciturn, blonde Swede standing beside a wood chipper…

‘Secrets of the Viking Stone’ goes out at 9pm on Sky History on Mondays

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks