The murder of Sean Brown: Inherited trauma in Northern Ireland

Twenty-five years have now passed since the murder of my father’s cousin, Sean Brown. The Troubles legacy bill does nothing to heal my family’s inherited trauma, writes Gemma Brown

On 12 May 1997, 61-year-old Catholic, Sean Brown, was abducted and murdered by loyalist paramilitaries while locking the gates of the Bellaghy Gaelic Association (GAA) club. Twenty-five years later and still no one has been charged with the murder.

The Troubles should be a lifetime away from me, a 22-year-old English girl born and raised in Blackpool. Yet when I was a child the whole thing seemed like a ghost story as my dad would tell me the tale of the murder of his cousin. The assassination of Brown remains an open wound worn by every member of the family.

My dad, Michael, tells me of the man who would drive him and his brother to Gaelic football matches and who built his father a greenhouse – the man who waved goodbye from the port as my dad sailed off to live abroad. “He was our leader,” he says. “Sean took the load for everybody. He was always looking to help people.”

The brutal details of Brown’s murder remain raw to his family. As chair of his beloved Bellaghy Wolfe Tones club, he stayed behind after the weekly meeting on the evening of 12 May to lock the heavy, wooden gates. It was then that he was attacked by several loyalist assailants and bundled into the back of his own red Ford Sierra. After an agonising 10.2-mile journey to Randalstown, he was dragged from the car and beaten. He was then killed with six bullet wounds to the head.

Brown was found abandoned beside his own burnt-out car, his body also partially burned from the intense heat of the flaming vehicle. As Irish custom dictates, his widow, Bridie, insisted on an open coffin, asserting that everyone should see what the attackers had done to her husband.

The killers chose Sean Brown because he was a Catholic. Yet everyone who knew Brown described him as a man of peace and goodwill. A man who served his community whether Protestant or Catholic, and cared for everyone no matter their politics.

“Our Sean was just an innocent man,” his younger brother, Chris Brown, tells me. “He lived for his wife and his family and for the GAA. He didn’t deserve the end he got.”

Now the family’s campaign for justice is under threat by a new bill set to be made law this autumn. The controversial Troubles Legacy Bill, due for a second reading at the House of Lords, aims to end Troubles-related prosecutions. It will close all criminal investigations, legal proceedings, inquests and police complaints once it comes into force. It also offers immunity from prosecution to those who cooperate with Troubles investigations. One consequence is that Brown’s inquest – for which the family have not yet been given a date – may never go ahead.

When Brown was younger he had performed in local plays produced by fellow Bellaghy man and world-renowned poet Seamus Heaney. “He represented something better than we have grown used to,” the Nobel literature prize winner said in a tribute to his friend in 1997.

Not only were the circumstances of Brown’s murder brutal, but the subsequent investigation – or perceived lack thereof – poured salt into the wound of many. Amid murky allegations of collusion and coverups, a 2004 police ombudsman report concluded that the investigation was, “incomplete and inadequate”.

The report is littered with a damningly long list of faults – including a failure to carry out a proper search for witnesses, a failure to deal with all forensic evidential opportunities and inadequate enquiries into the vehicle convoy used to carry Brown to his death. The ombudsman also highlights the disappearances of two key files: the murder investigation policy file, in which all decisions made during the investigation are detailed, and the Bellaghy occurrence book, a record of all matters reported to Bellaghy police during the relevant time period.

The aftermath of such failures by the police is 25 years of seeking answers and justice. Human rights group the Pat Finucane Centre offers support to bereaved families of the Troubles and has been involved in Brown’s case since the beginning. Director Paul O’Connor tells me of his own assistance to the Brown family as he joined them at court hearings dozens of times.

“There was delay after delay after delay,” he says. “It should have been resolved many years ago. We should not be, in 2022, in this situation where we’re waiting for an inquest into the murder of Sean Brown.”

A frequently-used word in the ombudsman’s report regarding the investigation is “limited”. Limited enquiries and examination. Limited answers and explanations. Yet what is not limited is the intense grief and pain felt by the Brown family to this very day. The endless hearings and decades of waiting are not limited. The immediate failures of the murder investigation team unleashed an unlimited torrent of hurt and trauma on the family of a man who deserves his basic right to justice.

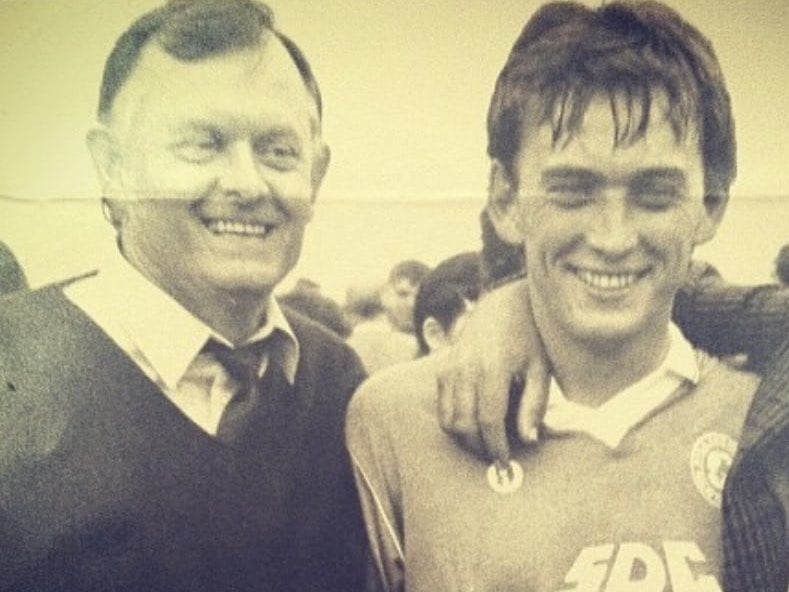

The purifying character of Brown today continues almost as folklore, lingering in the memories and the lives of his surviving family members. His son, Damian, bore a striking resemblance to his father – specifically in a shared warm, welcoming smile. He inherited his father’s great kindness and devotion to the community, making time for everyone who needed him. Damian wasn’t the sort of man to sit in the house and watch television. Instead, he would come home from work for his dinner and then head back out again, keen to help people and get jobs done for them. He, too, was fiercely committed to Gaelic football, playing for Bellaghy in the 1995 All-Ireland club final.

It was Damian who also determinedly carried much of the burden of his father’s death, striving for answers and justice for almost half of his life. He went to over 30 preliminary hearings but each time was left disappointed.

Damian’s eldest son, Damán, tells me of watching his father during those tough times: “I knew whenever he came in he would be quiet and I would see it was all just churning in his head. The different thoughts he would have been having and what his father went through that night. He never told any of us, but you knew. You knew he was feeling it.”

Damán’s younger brother Declan shares similar memories: “It was like he was protecting us and protecting Granny Bridie, he was protecting his own brothers and sisters. He took it upon himself to carry that mantle – and it was the exact same thing from the day Daddy got diagnosed.”

It was in July 2021 that Damian Brown was diagnosed with a brain tumour. “I could have known by looking at him that he wasn’t in great form,” says Declan, “but if I’d have asked him ‘how are you today?’, he would have just said ‘aye, I’m grand’.”

Just 11 weeks after being diagnosed, Damian passed away on 8 October 2021 aged 51. The loss was a huge blow to the Brown family – especially to his grandchildren.

In Heaney’s legendary literature Sean Brown is forever enshrined as a timeless symbol of peace and good-heartedness, one which is elevated beyond the complex politics of Northern Ireland

Declan was 27 years old when his father passed – the same age Damian had been when his own father died. It’s just one of a few haunting connections between the three generations of the Browns. Declan, like his father before him, plays for the Bellaghy GAA team. Gaelic football is interwoven into the DNA of the Brown family, with Sean’s own father, Jim Brown, being among the founders of the Wolfe Tones club. Yet this tradition put Declan in a difficult position when he was asked to play a match on the day of Damian’s funeral.

“My manager came into my da’s wake on the Monday evening, and me and him went into a room of our own,” he recalls. “He says: ‘I know the game’s on, and I don’t want to put you under any pressure, but I think it’s meant to be.” At first, Declan doubted his capacity to play the game, noting how mentally and physically drained he felt. Yet he reconsidered when he thought of his father. “If he was sitting and talking to me, he’d have been telling me to get the bag packed and to get to the football because he probably would have done the same if he had been in that position.”

And so on the evening of Friday 12 October, after burying his father that morning, Declan Brown came on as a sub for Bellaghy. At the final whistle, having beaten Newbridge with a late winner, there was a shared display of mourning amongst the Bellaghy team. The players and mentors sprinted and embraced their bereaved teammate in an emotional scene described as “the GAA at its best”.

It was a sight that Declan’s late father and grandfather would have surely been overwhelmingly proud to see – three generations tied together by the camaraderie and fighting spirit of Gaelic football. Such values are enshrined in the club’s plaque, which remembers Sean Brown’s service to “his club and community”. The murder has not tainted but strengthened the club’s importance to the family and the Bellaghy community. “The GAA club is the central hub of the whole community,” says Declan, “Your teammates are the fellas who will probably end up carrying you to your grave.”

Yet not even the wonderful support of his club can erase the long process of grief. “It gave me a bit of a false feeling,” Declan says of the winning match. “There was a bit of a buzz afterwards for a few days. People were congratulating you and praising you but, at the end of the day, that’s not why I did it. And then I suppose it sort of came as a bit of a crash. That was when I actually processed that Daddy’s away now. There was definitely a massive comedown from it.”

With Damian’s passing came the succession of his role as the driving force behind the Sean Brown justice campaign. It is a role that has now been taken on by Damán, who has had no doubts about continuing the struggle: “My father fought for years, fighting for his father and my grandad, so the least I can do is fight for the two of them.”

The proposed Troubles Legacy bill has angered people across the political spectrum, receiving opposition from all Northern Ireland MPs, all Westminster opposition parties, the Republic of Ireland, The Council of Europe Commission on Human Rights and Amnesty International UK. “At the moment we’re on a train that’s going 100 miles an hour along a track that ends at the edge of a cliff,” O’Connor of The Pat Finucane Centre says of the bleak situation. He believes that people, particularly in Britain, are not fully aware of the damaging consequences of the bill. “All we can do is protest against the dying of the light.”

MP Brandon Lewis, who acted as Northern Ireland secretary when the bill passed through the commons, claimed that the move would “help families and victims move forward.” According to Damán, he is wrong. “How can you move forward?” He says. “You never forget when a loved one has been murdered. You need closure to move on with your life.”

The actions of Brown’s family gracefully demonstrate to the government the importance of legacy and memory. In the spring following Damian’s death, relatives launched the charity event The Big Weekend in his memory to raise funds for the charities that helped him and the family. Through a range of activities – including a 10k run and 50-mile cycle – the event raised over £75,000 for Macmillan and Charis Cancer Care. Every penny donated was a reflection of the high regard that Damian was held in and the legacy that he holds today in Bellaghy.

“He was no celebrity by any means, he was your average Joe and he was well thought of,” Declan surmises, “And that’s what makes me proud – to know that’s the way my da was thought of in the community and further afield.” Damian will be remembered for his dedication to the people around him and especially to his mother, Bridie, whose house is now adorned with tributes to her late son as well as her late husband.

Such legacies will never fade and should never be forgotten. In May 2022, on the 25th anniversary of Sean Brown’s murder, hundreds of people attended a special commemorative event in Bellaghy. GAA President Larry McCarthy unveiled a plaque presented to the Brown family and planted a tree in Brown’s honour. “As they look on this oak tree as it grows and spreads its branches, they will look fondly on the lasting memory of Sean Brown,” Damán said at the ceremony. “He planted the seed of success and sense of community in Bellaghy that still continues to flourish until this day.”

Actor Stephen Rea read out Seamus Heaney’s “The Augean Stables” – a poem dedicated to Sean Brown following his death. Heaney compares Brown’s sportsmanship to the ancient Olympic spirit, guiding the reader through the mythological sites of Olympia. It was there that the poet learnt of Brown’s death and imagined “hose-water smashing hard back off the asphalt / In the car park where his athlete’s blood ran cold”.

In Heaney’s legendary literature Sean Brown is forever enshrined as a timeless symbol of peace and good-heartedness, one which is elevated beyond the complex politics of Northern Ireland. The commemoration was a sad day – one in which the Police Service of Northern Ireland publicly apologised to the Brown family. And a day that Damian was tragically not alive to attend. Yet it also served as a reminder that both of their memories will live on in the thriving grounds of the Bellaghy ‘Seán de Brún’ GAA club.

I am proud to be a part of the Brown family. Its essence is scattered across Bellaghy, rooted in the sunken boglands and cemented in the sturdy rock of the bawn. The hurt that Brown’s immediate relatives went through should not be experienced by anyone. Yet Brown’s case is just one of a thousand unsolved Troubles killings – killings that will remain unsolved if the Troubles Legacy Bill becomes law. The consequences are damaging: one person’s injustice is an entire family’s trauma, one that does not become extinct with time and faded memory, but passed on through generations.

Unresolved murders such as these serve as a reminder that we need answers to heal the wound, that we cannot move on from the past until the past is fully understood. It is only when we confront our history that the death of Sean Brown and other victims of the Troubles no longer seem like ghost stories, but tales of hope and healing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments