John Hume’s SDLP, the unsung hero of the peace process, turns 50

The party that battled bravely to bring an end to the Troubles – and establish a shaky peace in Northern Ireland – faces an uncertain future, writes Adam McGibbon

Today, a 50-year anniversary will pass without fanfare, despite its huge significance to the Northern Ireland peace process. The Social Democratic & Labour Party (SDLP) was founded on 21 August 1970, as Northern Ireland descended into chaos. The month before, the British army had alienated what remained of their support from the province’s Catholics by indiscriminately locking down the Falls area of Belfast, delivering a massive recruitment boost to the IRA. A few weeks before that, the army used rubber bullets on civilians for the first time. And just days before, two police officers were killed by an IRA bomb in County Armagh. Amid this turmoil, the SDLP was launched at a press conference in Belfast.

The SDLP is the party most responsible for Northern Ireland’s shaky peace. It took huge risks to achieve this. Some of the risks were political, some were physical: many of their representatives were threatened, assaulted, and a few were murdered. The recent death of the party’s most dominant figure, Nobel Peace Prize winner John Hume, overshadows the anniversary. He was a towering figure in Irish politics, perhaps the one person most responsible for the peace. But the SDLP was the vehicle for delivering it.

At its onset, the SDLP set out to create a united opposition against Northern Ireland’s dominant Unionist Party, which since 1921 had presided over a political system rigged against Northern Ireland’s Catholics, with built-in discrimination in housing, voting and employment.

The SDLP founders didn’t just want to replace the old Nationalist Party, the perennial opposition vehicle that was essentially a flag of convenience for numerous disconnected local political fiefdoms. They wanted to unite all shades of opinion: conservative farmers, Belfast trade unionists and the young articulate and educated Catholics, who were part of the emerging movement for civil and political rights. Bringing all this under one banner was an uneasy fusion – all previous attempts to do so had failed. The party’s first leader, Gerry Fitt, told his biographer of having “sleepless nights” about the different currents the party was trying to unite.

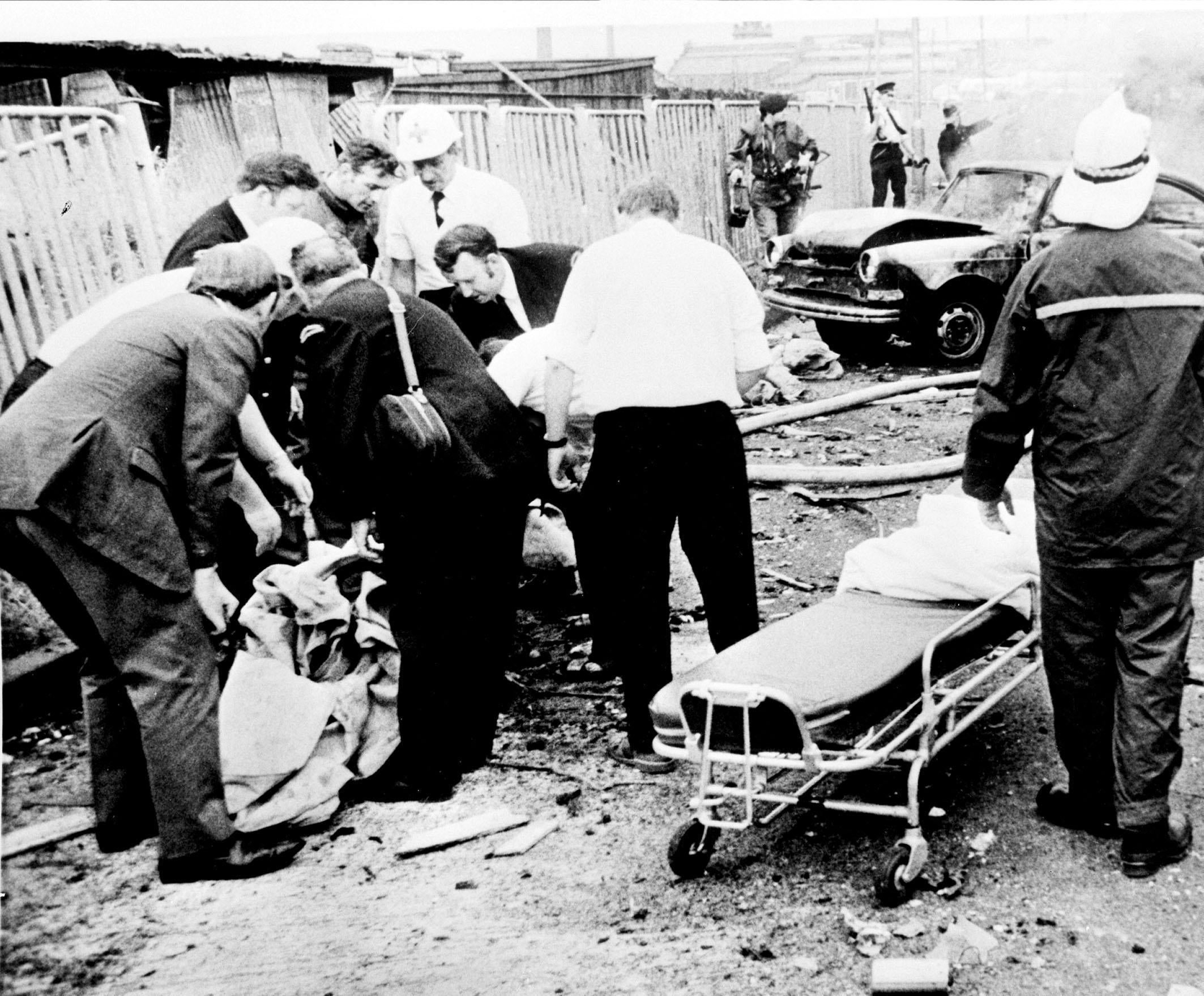

Many commentators predicted that the party wouldn’t last long, but it endured, in more ways than one. It endured violence and suffering. The incidents are too numerous to recall, amounting to outrages on the level of the 2016 assassination of Labour MP Jo Cox, but repeated again and again. Founder member Paddy Wilson was murdered alongside a friend in 1973, both of their bodies were found mutilated by loyalist assassins. Denis Mullen, an ordinary party member who was the chair of the local SDLP branch in Moy, County Armagh, was shot dead in 1975 by the Glenanne Gang – a loyalist gang colluding with the British state that had serving police officers in its ranks.

In 1974, leading SDLP members in a pub in Dungannon barely escaped alive after they discovered a bomb where they were due to hold a meeting. Former IRA member Sean O’Callaghan wrote in his 1998 tell-all book that in the 1970s, the IRA had considered killing the entire SDLP leadership. In 1983, the IRA firebombed John Hume’s election headquarters in Derry. A poignant photograph shows Hume inspecting the devastation. Brian Hanley and Scott Millar report in their 2010 book, The Lost Revolution, that an IRA faction had a spy working in SDLP headquarters, with full access to the names and addresses of the entire party membership.

The SDLP also endured the tragedy of the collapse of the 1974 power-sharing executive, set up under the British Government-brokered Sunningdale Agreement. For the first time ever, nationalists and unionists shared power, with SDLP members taking up government ministries. The SDLP negotiated this vision of power-sharing, pioneering the now common-sense solution that the only way to solve Northern Ireland’s woes was for historic enemies to share power, for the aspirations of nationalists and unionists to be equally respected, and for Northern Ireland’s future in or out of the UK to only change if a majority peacefully demanded it.

The power-sharing executive collapsed in tragedy, brought down by a general strike enforced by loyalist paramilitary groups and whipped up by a band of demagogues, among them Ian Paisley

They had already been practising what they preached, sharing power with unionists in local councils where the SDLP was the biggest party. Unionists did not reciprocate. The power-sharing executive collapsed in tragedy, brought down by a general strike enforced by loyalist paramilitary groups and whipped up by a band of demagogues, among them Ian Paisley (who would much later sit at the head of a power-sharing system he once opposed). The failure of Sunningdale consigned Northern Ireland to a further 20 years of violence, but the SDLP had established the blueprint for a future settlement.

It endured splits, like founding members Gerry Fitt, Paddy Devlin and their followers leaving the party with their supporters, saying the party had ceased to be – or perhaps had never been – the socialist force it claimed to be. They believed that an over-emphasis on Irish nationalist aspirations had made it impossible to attract Protestant support, that the party had been taken over by the middle classes, and that social justice had taken a back seat to the aim of a United Ireland – all charges that would surface again and again.

Splits also developed as Hume unilaterally took a huge risk by talking to Gerry Adams, the president of Sinn Fein, the IRA’s political wing. He famously declared that if negotiating with Gerry Adams to try to end the violence would save one life, he would do it no matter what. He was vilified for doing so, inside the SDLP and out. But this action was the beginning of a process that led to paramilitary ceasefires, and ultimately, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

When peace came, and with a power-sharing government in place, it was the SDLP which was the main author of that peace. It was with a combination of bitterness and wry humour that the party’s Deputy Leader, Seamus Mallon, a formidable Armagh headmaster and the Deputy First Minister in the new power-sharing executive, declared that the 1998 peace settlement was “Sunningdale for slow learners.“

But from struggling for peace, they are now struggling in peace. The SDLP has a proud legacy, but an uncertain future. In the euphoria of the 1998 elections to elect the new Northern Ireland Assembly, the SDLP won the most votes, even more than the dominant Ulster Unionist party. Since then, the party’s fortunes have declined in every subsequent Assembly election.

By helping to bring Sinn Fein into the democratic process and away from violence, they have created a formidable enemy that has eclipsed their position as the leaders of the nationalist community

They are the authors of peace, but also the victims of it. By helping to bring Sinn Fein into the democratic process and away from violence, they have created a formidable enemy that has eclipsed their position as the leaders of the nationalist community. Sinn Fein, for all its faults and baggage, appears more energetic, less tired, and more dynamic than the SDLP. They have almost fully co-opted the SDLP’s language of understanding, acceptance and focus on power-sharing, which the SDLP’s detractors used to mock as Humespeak.

The SDLP’s selling point during the Troubles was that it was the non-violent nationalist party. With Sinn Fein now occupying this ground too, appeals to the SDLP’s history are increasingly inadequate as generations come of age who haven’t lived through the Troubles.

Finding a new unique selling point in more progressive politics, like Fitt and Devlin had wanted 50 years ago, is also fraught with problems because it awakens some of the tensions evident at the SDLP’s founding, which have become more pronounced in peacetime. Tensions between urban social democrats and rural conservative nationalists have thrown up a range of painful spats. A proposed merger with the Republic of Ireland’s right-wing Fianna Fail party raised the hackles of party members more likely to identify themselves with the Labour Party.

The SDLP’s South Belfast Assembly member (and now MP), Claire Hanna, seen as being on the party’s progressive wing, resigned the SDLP whip over the move, although remained as an elected representative. The party was perceived as taking far too long to get on the same page over the issue of same-sex marriage, with rows breaking out between factions, and elected representatives quitting over the eventual stance of support for the policy Division over party policy on abortion, between pro-life and pro-choice factions have led to a range of defections and resignations of elected representatives. More trouble brews as the SDLP tries to work through the tensions that gave Fitt sleepless nights in the 1970s.

The very existence of that imperfect, democratic power-sharing framework is crucial as a foundation for building a more solid peace. The SDLP realised how critical this was

This leaves the SDLP overly dependent on the personalities of its founding generation. SDLP literature places a large emphasis on Hume and of its role in the peace, but has much less to say about post-1998 politics. This appeal becomes more faded every year. For nearly two decades before his death, the party had been deprived of the brilliance of Hume by the cruel and tragic onset of dementia, to the point where Hume couldn’t remember his vital peacemaking role. Hume’s importance is underlined by current party leader Colum Eastwood, whose appeal for SDLP votes in the 2019 European Parliament elections centred around the need to “take back John Hume’s seat” – a seat in the European Parliament that Hume had vacated 15 years before. The party failed to take it back, leapfrogged by the centrist cross-community Alliance Party.

As the founding generation passes into history, it will be harder to keep hold of the ground won. As well as Hume, two other major figures passed away recently. John Dallat died in May 2020. Born in a house with no running water, he rose to be Deputy Speaker of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the first Catholic Mayor of the north coast town of Coleraine. He endured constant death threats representing his constituents and was forced to sleep with a gun beside his bed for protection. Seamus Mallon had died a few months before in January.

In some ways, the modern SDLP has ended up like the old Nationalist Party it replaced – a fragmented organisation heavily dependent on local personalities for electoral support. The slow disappearance of these personalities puts the party in danger. The Nationalist Party had a strong clerical influence and it’s hard to not see this reflected in the SDLP’s slowness to embrace LBGT equality, in its division on abortion, and in a Catholic bishop’s ‘surprise’ in 2016 of the SDLP coming out in support of Catholic and Protestant children being taught in the same integrated schools. It’s slowness to fully embrace this much-needed reform – opposed by the Catholic church hierarchy, but a no-brainer to more progressive elements – speaks volumes of the tension at the heart of the party’s identity.

The nostalgia for the towering achievements of Hume will not solve the SDLP’s dilemma of what it is for. It faces opponents with more sharply-defined missions. They are under pressure from the Sinn Fein machine everywhere, and in urban areas are beginning to be challenged by cross-community parties like the increasingly confident Green Party and the socialist People Before Profit Alliance.

Nor can the party rely heavily on its achievements in government. The set-up of the power-sharing executive, with all major parties grouped into a mandatory coalition, means that there is little the SDLP can point to as its own achievements in government, as all decisions are taken collectively.

Some of the SDLP’s more prominent actions in government are not rosy ones: the SDLP’s Sean Farren had the unenviable task as Education Minister to introduce the first university tuition fees to Northern Ireland. Mark Durkan, Hume’s successor as party leader, did little as Finance Minister to put a social democratic or labour spin on his budgets.

Northern Ireland remains a criminally unfair place. Most schools are still segregated, with 93 per cent of students attending schools dedicated to one side of the community. Division remains, with more than half of the “peace walls” dividing communities being built after the 1998 peace agreement. Austerity means social ills go unsolved. Nearly 20 years of on-again-off-again power-sharing has buffeted a fragile framework.

But the framework stands, and for all its faults, for all the more that we wanted to see done by now, and for all that we have left to do, we have the SDLP to thank for the framework – even if the future seems likely to be uncertain for the party.

The very existence of that imperfect, democratic power-sharing framework is crucial as a foundation for building a more solid peace. The SDLP realised how critical this was from the very start of the Troubles. Without this, as Sean Farren wrote in his book on the history of the SDLP, “the situation would deteriorate to the advantage of those who claimed democratic politics would solve nothing”. We have been given something to build on.

A few years before his death in 2015, Seamus Mallon was asked by the BBC’s William Crawley, if it had been worth it. “The sacrifices, the risks that were taken...particularly by yourself and John Hume and the SDLP. Was that sacrifice worth it for your party?”

Mallon replied: “Not for our party ... (but) for the people of the North of Ireland in terms of peace – it was worth it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks