Even for Pussy Riot, gender equality must begin at home

In their first exclusive interview since they were granted asylum in Sweden, Pussy Riot stalwarts Lusine Djanyan and Alexey Knedlyakovsky talk to Harriet Marsden about not-so-political art, fighting over their image and how Russia needs to catch up post-MeToo

In Pussy Riot, male members are in short supply. But while the Russian punk feminist collective does not have a defined list of participants, one man, Pyotr Verzilov, is usually included. The husband of Nadezhda “Nadya” Tolokonnikova (the group’s most famous member), is well known thanks to fighting with his wife while she was in prison, gatecrashing the 2018 football World Cup final in Russia and the fact that he was poisoned last year, allegedly by intelligence agents.

Far fewer have heard of the artist/activist Alexey Knedlyakovsky, who is married to another Pussy Riot stalwart, Lusine Djanyan – but in fact, he was the first male member of Pussy Riot. The pair were granted asylum in Sweden this year after death threats were made against them and their two children. Last week, the couple gave a lecture on art activism at the 2019 Astrid Lindgren Conference in Stockholm. Afterwards, The Independent met them for their first exclusive interview.

It was, in many ways, surreal, not least because Knedlyakovsky claimed that art could not be political (despite his lecture) and, when discussing feminism, repeatedly talked over his wife.

They don’t look like typical punk anarchists. Djanyan is tiny, pixie-pretty with huge eyes and irrepressible curly hair. She giggles with the warm energy of a primary school teacher. Knedlyakovsky, on the other hand, is tall, conservatively dressed and bespectacled with an unperturbed drawl. He looks like he’s come to fix the printer. How, I start by asking, did they first come to be involved with the anarchist group?

“No, no answer,” says Knedlyakovsky, arms crossed.

Noting my flummoxed face – they’ve just given a lecture under the explicit banner of Pussy Riot – Djanyan clarifies: “Before Pussy Riot, during Pussy Riot, and after Pussy Riot.”

Knedlyakovsky then expands: “We are artists with our own career. So we can say that we took part in Pussy Riot, and we are connected with Pussy Riot, and we were members of Pussy Riot, but the first thing is we’re artists with our own careers, just like everyone who was involved in those actions. Some were film directors, some are artists, another is just a journalist maybe, or something.”

He’s looking straight at me, so we move on. While Knedlyakovsky would not explain how he became involved, he was definitive that he was the first male member of Pussy Riot, while Verzilov was the second. But, Djanyan explains, it was “a long fight” with Tolokonnikova.

According to the pair, Russian activism “ceased to exist at the turn of the 1990s”. During the early Noughties – the heyday of Putin’s stability, before the financial crisis – young people focused less on politics than careers and money. The natural resources sector was booming. But by 2007, a large group of relatively privileged, educated artists began to perform protest stunts in public spaces, gaining both popularity and notoriety in the media. They were “Voina”: an activist art collective.

Voina signalled a resurgence in Russian activism, but the stunts grew increasingly controversial – including a public sex scene at the State Biology Museum. By around 2009, the group had two distinct factions. The more radical St Petersburg strand became notorious for a stunt where a woman shoplifted a chicken from a supermarket by concealing it in her vagina. Meanwhile, the Moscow subset, led by Tolokonnikova, was more interested in pursuing feminism and women’s rights. Djanyan explains that Tolokonnikova fought with the original group because it was like “a male group, male power, and women presented just as objects”.

Knedlyakovsky interjects: “After that, I fought with Tolokonnikova for six years.”

I ask why. Djanyan explains that Tolokonnikova felt that Voina needed a more feminine, feminist faction, and then “suddenly in comes Knedlyakovsky, which sounded a bit weird to have a man in this group – but then it would also be discrimination against him, based on sex… but it was not that straightforward to have a man in this group. But he was not the only one, he was the first.”

In 2011, the group (still known as Voina) released a video on YouTube of young women jumping on female officers to kiss them – in conservative, anti-LGBT+ Russia, no less. By the the time Putin announced his return to the presidency, there were discussions about what would later become known as Pussy Riot.

After the December elections, tens of thousands came out to protest in Moscow, sparking a six-month wave of the most significant civic action since the collapse of the USSR. The government ordered its forces to quell the protests, and in February 2012 the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, Bishop Kirill, condemned the citizens. Meanwhile, tightening of regulation over abortions and women’s rights drove the nascent Pussy Riot to action. Explicitly paying homage to the “riot grrrl” punk movement of the 1990s, this was explicitly feminist protest art in the form of short guerrilla performances.

On 21 February, five young women in brightly coloured dresses and Eighties acid tights, balaclavas over their faces, broke into the main Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow. They sang an expletive-ridden song condemning Putin and appealed to the Virgin Mary, “a feminist who’s with us”, asking her to chase him and the establishment away. Pussy Riot (as we now recognise it) was born.

Djanyan clarifies that despite the enduring association in Russia, Voina and Pussy Riot are absolutely different groups with different philosophies and viewpoints. “Both groups have documentation of the action as the art form – the film, the photos, the description … it’s just that with Voina they have longer descriptions, and Pussy Riot is shorter, more visual, more into videos. Voina is much more radical. Pussy Riot is radical in their world view and what they say, but not so much in the action.”

Knedlyakovsky, however, insists that there is “no purpose” to Pussy Riot. Then, he says: “Art is the purpose. Art never wants political power. It’s hard to speak about some political philosophy when art is the main purpose. I’m against something like political art, when you use art as politics, this is not political.”

But isn’t a song condemning Putin – by definition – political? “We can talk about art, or not art. But art can’t be political.”

The art was political enough, however, for three of the women – Tolokonnikova, Yekaterina (“Katya”) Samutsevich and Maria Alyokhina (known as Masha) – to be charged with hooliganism motivated by religious hatred. The other two have still never been identified. Knedlyakovsky and Djanyan cannot name them or confirm whether they are still in Russia.

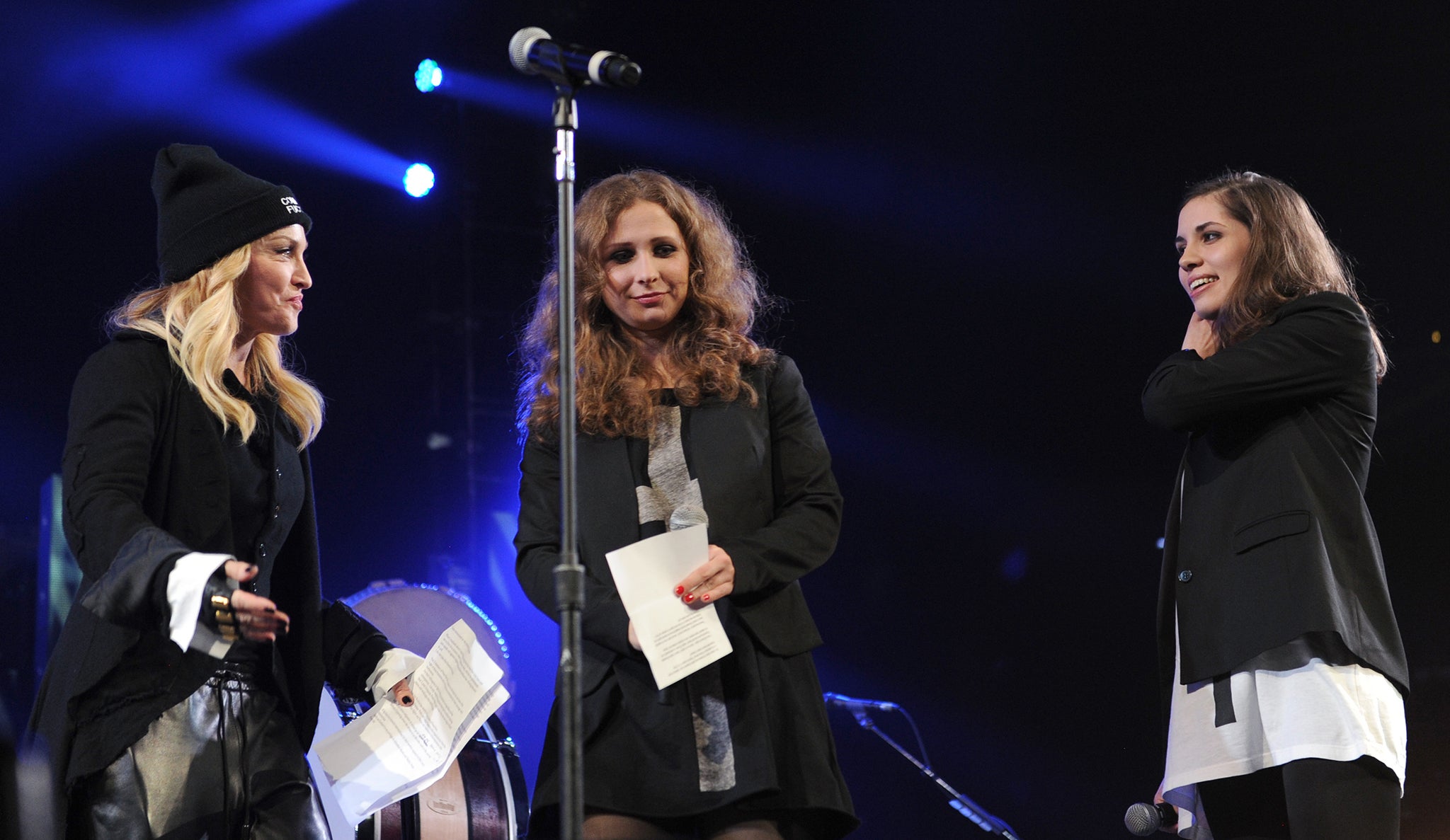

Meanwhile, musicians like Madonna and Sting called for their release. Pussy Riot had gone global, and their distinctive look became recognisable all over the world. During the trial of Alyokhina, Tolokonnikova and Samutsevich, even Björk dedicated a song to them. The German Bundestag pleaded with the Russian ambassador to free them, and supporters took to the streets of Berlin in balaclavas.

In any case, in August 2013 Samutsevich was released on probation but Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina were sentenced to two years in what Amnesty International would call “a bitter blow for freedom of expression”. The sentences sparked international protests and 17 August was declared “Pussy Riot Global Day”. The group were even name-checked on South Park.

Russian society was divided – many Orthodox, conservative people were horrified at the sacrilege, but many felt that the sentence was much too harsh. “Even people who were against Pussy Riot said, two years in prison? That’s impossible,” says Knedlyakovsky. “Just give them a fee or one month or something, let them go.”

On the global response, Knedlyakovsky says it was the first time that international media supported ideas brought up by artists, rather than specific personalities. “It was very obvious that the support was for the entire idea and what [Pussy Riot] stands for, but it’s a pity that the rest of the artists and opposition activists don’t get such support, because it’s needed. It’s hard for people who fight the regime every day … this contrast is painful.”

The group was divided by more than just bars. A conflict was growing over the question of commodity and the capitalisation of their art. In response to the public support, members reiterated that they would only participate in illegal performances, and would refuse to perform “in a capitalist system” where tickets are sold. But in September, an ebook entitled Pussy Riot! A Punk Prayer for Freedom – a compilation of letters, lyrics and poetry – was sold to raise money for the trio’s legal defence. A documentary of the same name debuted at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, featuring interviews with families of the group. Katya gave a Skype interview at the premiere, saying that she “rejected” commercialism of any sort. “We will never commodify our art.”

Tolokonnikova’s husband Verzilov began to give interviews for Pussy Riot, painting himself as their spokesman and making decisions for them – even accepting a hefty $50,000 peace grant from Yoko Ono on their behalf. Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina became international celebrities. That didn’t sit well with an anonymous, punk-feminist ideology.

Tolokonnikova had had enough. In a handwritten letter from prison, she accused her own husband of co-opting Pussy Riot’s message. “His statements are lies, in the name of giving himself the status of the founder and legal representative of Pussy Riot, when in fact he is not … In essence, Pyotr strangely quasi-conned and occupied the work of Pussy Riot. As a representative of the group, I am outraged.”

But Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina’s fame continued to grow as they began to protest the appalling conditions in the prisons – torture, exploitation, psychological pressure – and Tolokonnikova went on hunger strike. After increasing international pressure, Putin declared an amnesty in December 2013 for at least 20,000 Russian prisoners, including Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina. Djanyan and Knedlyakovsky are adamant that this was a political decision to improve Putin’s image on the eve of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. The pair were released.

Djanyan and Knedlyakovsky, along with Tolokonnikova, Alyokhina and others, protested at the Olympics in February. Cossack security guards attacked the group with whips and pepper spray, and the incident was caught on camera by a Vice reporter. The video, which Knedlyakovsky and Djanyan play in their lecture, is harrowing. The girls, so small in the hands of the Cossacks, are grabbed, de-masked, thrown to the floor and whipped. Knedlyakovsky’s head is severely bloodied. The police at the scene ignore the group’s pleas to arrest the Cossacks.

Just two months later, at a summit in New York, Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina posed with Hillary Clinton for a picture. They later performed at the Amnesty International concert in New York, invited by Madonna, which was described by the organisation as the “first legal performance of Pussy Riot”.

This time, it was the rest of the group that had had enough – ironically, with another open letter, which stressed that Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina were no longer Pussy Riot. It said they acted in their own names, and that the “headlines still full of the group’s name” and the public appearances described as Pussy Riot were misleading. “Our performances are always ‘illegal’, staged only in unpredictable locations and public places not designed for traditional entertainment.”

We had more freedom 20 years ago, in the 1990s, when there were speeches and discussions about feminism and transgenderism. Now we go back, like we live in 19th century Russia

The group also took issue with the poster of the event, which showed a man in a balaclava, calling for people to buy expensive tickets. “We are a female separatist collective. No man can represent us either on a poster or in reality.”

One wonders whether this is why Knedlyakovsky is so reluctant to explain how he is involved with Pussy Riot: for fear of seemingly “co-opting” a feminist message or mansplaining his own wife. Although, he reflects that “it’s interesting from an art perspective”, because when a man ran onto the field at the 2018 World Cup in Russia, “it looked very natural that there was a man among them, so people started to accept it”.

The problem with being viewed – or interviewed – through the prism of feminism is the vast distance between Russia and the west in terms of progress towards gender equality. The Pussy Riot brand of feminism is necessarily political, protesting against the authoritarian oppression of sexual freedom and basic human rights in Russia – rights which have long been (purportedly) achieved in the west. It’s not comparable to the commercialisation of “empowerment” and girlboss fandom in the UK, where we lean into the idea of post-feminism despite an enduring gender pay gap, assault and femicide.

While Djanyan struggles to elucidate this, Knedlyakovsky takes a phone call, despite sitting right next to her, before interrupting several times. At one point, Djanyan has to put her hand up to his face in a “stop” motion in order to quieten him.

“First of all, feminism in Russia is like a curse word. And that’s interesting because during the Soviet Union, women could vote two years before they could vote in Sweden, for example,” Djanyan says.

Knedlyakovsky explains: “We had more freedom 20 years ago, in the 1990s, when there were speeches and discussions about feminism and transgenderism. Now we go back, like we live in 19th-century Russia. We have a small part of society that is educated and young who can speak about feminism or transgenderism, but not many people are interested in that. For a lot of people, the first interest is how to survive, where they’re going to find the money to buy food. That’s real now, that’s what Putin did with the Russian economy, six years on from the annexation of Crimea.”

I ask Djanyan whether there are divisions in the Russian feminist movement over trans women. She points out that any form of official LGBT+ education or information is forbidden in Russia, and that according to the state, trans people are “psychologically sick”. Although legally you can change gender and get a new passport, practically speaking “you’re going to go through hell”. Feminism, she says, is not about “this faction or that faction”: it’s about “basic human rights, right now”.

As tensions have continued to mount for Russia this decade – war with Ukraine, the occupation of Crimea, the shot-down passenger Boeing, bombing in Syria – there has been a domestic crackdown on artistic activism. Djanyan grew accustomed to being attacked just sitting and drinking coffee. “You get used to it,” Djanyan shrugs. “You think it’s normal when you’re being followed, when they listen to your phone calls, when you get beaten up, that’s the reality you live in.”

Djanyan compares the crackdown to censorship of Pussy Riot videos on YouTube. The original video from the cathedral was removed for violating the platform’s rules on discriminatory speech. “The problem of freedom of opinion and freedom of expression is very acute in the modern world,” she says.

Some women really want to fight for their rights … and some women don’t really understand. They think it’s an OK situation that we’re in right now in Russia. They take it as a status quo. The main purpose of the female in Russia is to get married well

But threats made to the couple’s children were “the last straw”. The couple fled to Sweden on their visas and applied for asylum. It was denied. The ruling, says Djanyan, was “really ridiculous. When we read this, we really laughed.” (She’s still laughing about it.) “We laughed about this refusal because the reason was ridiculous: they said that in Russia, they’re trying to build a democracy … which is like saying to Putin, you’re doing well.”

Unlike many asylum seekers from Russia who are turned down by Sweden, they appealed the decision and eventually were granted refuge. “It says more about the Swedish system,” says Knedlyakovsky. “It’s more like Russian roulette.”

The pair now focus much of their artistic activism on the plight of migrants and refugees in Sweden. “The journey of refugees to Europe is well documented,” they said in their lecture. “But what happens to these people when they get here? In Sweden, they live for years in obscurity without rights, waiting for the decision of the migration board. They know nothing about their future. Many people … compared the waiting period with psychological torture.”

Knedlyakovsky stresses that it’s injustice which drives him to create art – despite his earlier apolitical position. “Modern art is dangerous for totalitarian regimes because modern art shows the problems that regimes try to hide. In any case, even in Sweden. If you try to hush up some problems, here comes the art. In Sweden we also have things that are silenced. Art takes it to the surface.”

The interesting thing about being abroad, he says, is that you can still fight the Putin regime – “sometimes you can do even more than you can inside Russia … Sweden had a strong relationship with the Soviet Union and now Sweden has a strong relationship with Russia – more than 500 Swedish companies have business in Russia.”

We speak about the upcoming US elections, and the extent of Putin’s involvement – or manipulation – of western politics. While Tolokonnikova and her iteration of Pussy Riot have stormed Trump Tower in New York, spoken about the Trump-Putin relationship and even released a song, Djanyan and Knedlyakovsky are more circumspect, and reluctant to be drawn.

Knedlyakovsky says that it’s almost impossible to predict what will happen given that Putin has changed the face of international politics so much. “The troll factories are a drop in the ocean as it relates to impact. Over the last 20 years Putin has had a direct influence over the world’s leaders and he will definitely have an influence in the elections … although no one really knows how much money is pumped into American politicians and which politicians the money is pumped into.”

Does he think Putin bought Trump? “He definitely has money to do that. And Trump loves money so much that you can never exclude anything.”

We talk about the difference between the #MeToo movement in the US and in Russia, where victim-blaming is still the norm. Djanyan says: “If a woman says she’s abused she will be viewed as though it was her fault. If you go to the police they will tell you you were probably dressed inappropriately to attract that type of behaviour or you were drinking. Socially there is a stigma and you will be smeared. The #MeToo movement or anything like that is really needed here so that this topic can be talked about, because you have to talk about it in Russia.”

Knedlyakovsky also brings up Oleg Sokolov, prominent historian in his sixties who confessed to murdering his partner, Anastasia Yeschenko, in St Petersburg, chopped her up and put her body parts in a backpack. Drunk, he fell in the river trying to dispose of it. She was 24. Djanyan explains that there are still people in Russia who say that maybe she was “bad to him”: “maybe she made him jealous”. That’s a good picture of how people react to these kind of things, she says.

Djanyan says: “The situation is absolutely horrible – there are official lists of professions that women cannot work in, and domestic violence is a huge issue. It’s a very small fraction of people that call themselves feminist: the rest look at them as crazy people. In Russia you really fight for your rights still. Domestic violence is decriminalised now, and there are many medieval things that you have to fight.”

Knedlyakovsky cuts in: “Some women really want to fight for their rights … and some women don’t really understand. They think it’s an OK situation that we’re in right now in Russia. They take it as a status quo. The main purpose of the female in Russia is to get married well.”

So it seems that even for Pussy Riot, feminism begins at home.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks