For South Africa, the past is harder to escape than a prison

‘Escape from Pretoria’ is the story of Tim Jenkin and Stephen Lee, two white South Africans branded as terrorists and imprisoned in 1978 for anti-apartheid activities. While they were held, they crafted wooden keys for 10 steel doors and broke free. Now, 42 years later, Stephen Applebaum talks to them

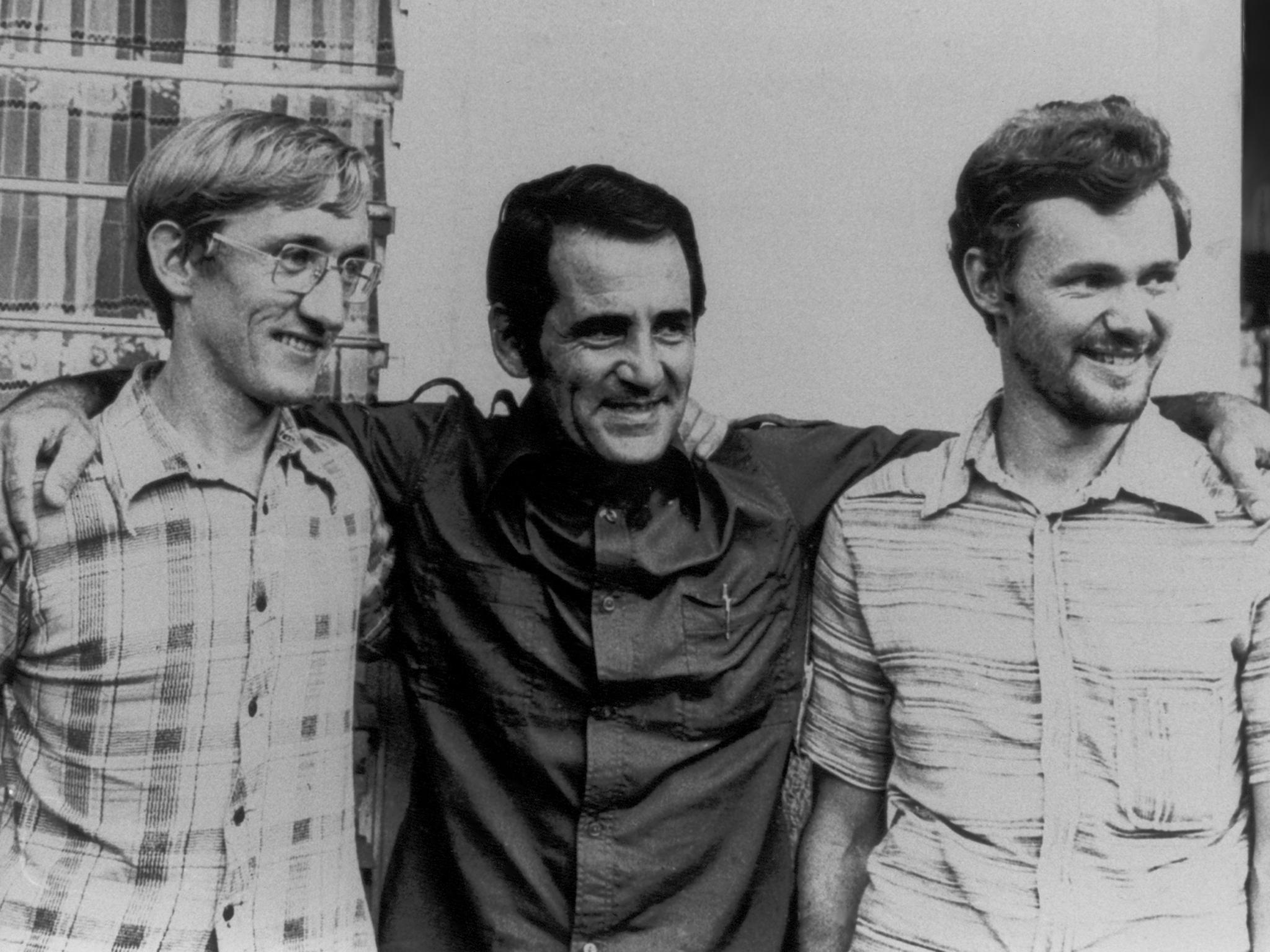

When Tim Jenkin, Stephen Lee and Alex Moumbaris escaped fom Pretoria Central Prison, using the same wooden front door through which they’d entered the facility at the start of their sentences, their breakout would have been flawless but for Moumbaris forcing it open with a chisel. They had left no evidence along their route from the political prisoners’ section, and were it not for the signs of brute force used on the last of the 10 doors that had stood between the jailed anti-apartheid activists and freedom, it would have appeared as if they’d simply vanished into thin air.

On the phone from his home in Cape Town, Jenkin says he had attempted to convince Moumbaris that they should return to their wing and try again another day. It wasn’t as if this was the first time they had slipped from their cells and crept through the prison using wooden keys they’d made. Moumbaris and Jenkin had even gone all the way to the final door before, but hadn’t ever tried to open it. When they did, they discovered that none of their homemade keys worked. What would another short delay have mattered while they perfected the key for the “ordinary house lock” that was frustratingly impeding their exit?

“He said, ‘No, we’re not going back. There is no guard outside. There is only one direction we’re going in,’” says Jenkin, recalling the moment in December 1979. “I was trying to argue that it’s crazy because we wanted to pull off the perfect escape. We hadn’t left a trace. We had locked everything behind us. We hadn’t even left fingerprints. We were wearing gloves. We were wearing balaclavas. There was absolutely no way they could have figured out how we got out. So once he dug that chisel into the door frame, I realised that there’s no going back. Even if we had gone back, how do you explain a broken door frame? That would have been the end. So we decided to go at it.”

Jenkin told the story of how the three men had managed to escape from the high security prison – and much more besides – in his 1987 book Escape from Pretoria. It was banned in South Africa but finally went on sale there in a second edition in 2003. From the day the book appeared, filmmakers took an interest, and Jenkin found himself signing new contracts almost every five years.

Eventually, producers who had first attempted to make a film 16 years ago managed to raise the money at a second try, and Escape from Pretoria is now hitting cinemas as a taut, fast-paced thriller with Daniel Radcliffe as Jenkin and Australia’s Daniel Webber as Lee. Moumbaris is played by Mark Leonard Winter, although in the film he is renamed Leonard Fontaine.

“This was a choice that Alex made,” explains Lee, who now lives in London with his wife and family. “I’m still in touch with Alex, and he’s a friend and a comrade, but all three of us don’t see eye to eye on every point. So this was just his decision and we’ve respected it throughout.”

The film covers the nearly two-year period from the time Jenkin and Lee were arrested to their escape in an “abbreviated” version of events that “can’t possibly be really accurate,” admits Jenkin. “But it’s the general story and some parts of the film are very accurate.”

He flew to Adelaide where the exterior of a former prison-turned-museum stood in for the outside of the prison in Pretoria, as well as providing the location for a visiting room scene. “The outside was very different to our prison, but no one knows that,” he laughs. “The interior was a mock-up, a cardboard and wood thing. They made it look a bit more grim, paint peeling off and all that kind of stuff, but the shape of it and layout was pretty accurate.”

He worked with Radcliffe to help him with his South African accent, and later in Australia was on hand to answer the actor’s questions about motivation and anything else he needed to know. Jenkin even got to appear beside the Harry Potter star in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo.

“Seemingly a lot of people were quite scared because I was there,” he says. “They actually told me that they were quite nervous when I was around.”

By focusing so tightly on events after Jenkin and Lee had been working for the ANC, the film misses out the journey that the men – Jenkin especially – had to take to break free of the apartheid regime. They had to escape the chains that bound them as white South Africans to see the reality of the country in which they were living.

When their their paths crossed at the University of Cape Town, where they studied sociology together, Lee “was more advanced ideologically,” says Jenkin. “For a start, Stephen had been at university for a year. And also he had a different life experience. He started reading books when he was at boarding school in a small rural town, and I think he experienced things that I didn’t. Whereas for my ideological development, I had to leave the country to find out about [what was happening].”

Lee insists that “anyone who opened their eyes knew what was going on”. He had been just 10 or 11 years old when he asked his parents about slogans he’d seen that were written after the ANC was banned in 1960. “I suppose that exhibited an early interest in politics,” he muses, “although I didn’t recognise it as such.” Most of the slogans got erased, but he says one stayed up for years: “Remember Sharpville”. It was originally meant as a protest, following the regime’s massacre of demonstrators in the Sharpville township but, says Lee, “subsequently I have realised, with horror, that it was left as a warning.”

At school, Lee read books such as Let My People Go by Albert Luthuli, the leader of the ANC, and Trevor Huddleston’s Naught for Your Comfort, and was already a “committed anti-racist and, in some vague way, a sort of social democrat” when he left. “I had those feelings,” he says. “They crystallised much more in my first year at university.”

Jenkin is honest about the slow pace of his own political awakening, and in his book talks about absorbing, as a privileged, middle-class white boy, “the normal white prejudices against blacks” and bearing “a ‘healthy’ hatred of them.”

He says that when he matriculated at 17, he “knew nothing and had no political idea. I went to a white school. I lived in a white suburb. I had no black friends. In fact the only black people I came in contact with were servants and gardeners, things like that, or maybe workers in the street, and I didn’t really engage with them. It was a completely divided world. We had our own shopping areas and they had theirs. There was no reason why we should ever meet.”

Family and friends who’d come to the UK and seen documentaries critical of the situation in their homeland would often talk about seeing “terrible, nonsense propaganda films”. Jenkin was expecting to be amused by them when he took a boat to Britain in April 1970 to visit relatives in London and work, and because so many were being broadcast at the time, he didn’t have to wait long to watch one. On the day he arrived, he “saw that something [about South Africa] was showing. I thought, ‘What a load of propaganda nonsense. It is not true. I have lived there for 20 years and never seen anything like this. Why are they making these films?’”

At first he defended white South Africa. However, the troubling questions and harsh criticism of apartheid kept coming, and the more he saw and heard, “the more I realised there was a reality I didn’t even know about.” Jenkin’s education was just beginning. He watched more documentaries and read a ton of books, including ones banned in South Africa, and at the end of 1970 decided to continue his learning in a more structured way at university.

“It was strange coming back home again because I was now among people who were ignorant, and I could see the ignorance for what it was. Suddenly I was back in this kind of fog again where nothing was explained and as if nothing was going on, and everybody was just happy with their lot. I could then see through the mist and knew where to look and knew what to look for. That made me very angry and suddenly wanting to do something about it.”

Naive about the risks involved, Jenkin returned to South Africa with “all kinds of literature that was banned”. At university, he and Lee discovered that there was “a sort of underground of banned literature”, while the government itself produced a weekly list of proscribed books and publications. “That was very useful to us because if something was banned, we knew it was something worth reading, and those were the things to try and get hold of.”

“Tim and I progressed together,” says Lee. “We started to find that we could get hold of a certain amount of the [liberation] movement’s literature. The Communist Party used to circulate something called African Communist, and we’d occasionally get hold of miniature versions of that.”

Politically, there were “no options to do anything practical or revolutionary,” says Jenkin, because the only existing political organisations were ones “that were approved, in a sense. You had your white political parties. All black parties were banned or operating in exile. So anyone who stood up with alternative views would get shutdown or banned, ostracised or sent away, or imprisoned. So people were fearful.”

If they were going to do anything, they needed to look outside the country. In April 1974, Lee and Jenkin arrived in London to find out more about the political parties opposed to apartheid. They found that the ANC was “the most welcoming,” says Jenkin. “And it seemed to be the one that was doing the most and had the biggest following. Also, the anti-apartheid movement in the UK fully backed the ANC, so it seemed to be the obvious way to go.”

Although it wasn’t unknown for white South Africans to want to join – they met some others in prison – Jenkin concedes that it must have been quite strange when they walked into the ANC’s office and said where they were from. “London was crawling with South African spies, everyone knew that,” he says. “So they didn’t know if we were spies or agents trying to find out a bit more, or trying to work out their procedures, or what they do with people like us.”

We had to lie to our family and friends about where we disappeared to all the time and what were our political views. So they had the opposite impression of what we really were

It took the ANC almost a year to send them back to South Africa. In that time they waited while the organisation, presumably, checked out their backgrounds, and taught them to do underground propaganda work, involving writing, producing and distributing political propaganda material “for and in the name of the liberation movement”. As part of this training, they learned how to make ‘leaflet bombs’ – non-lethal timed devices which used a small amount of explosive to send pamphlets 15-20 feet in the air.

Watching them go off when the friends were finally operational could be thrilling, says Lee, but it also helped them to learn how to maximise their effectiveness.

“We were passionate about what we were doing and it was a matter of great interest to us to see how well the pamphlets flew up in the air and where was the best kind of place to put [the devices]. We decided it was best on a windy day because the pamphlets blew further, and it was less likely that the police would arrive and gather most of them up. Which, I think, in many cases, they did.”

The deeper into underground work they got, the more exciting it became, says Jenkin. However, it could also be quite lonely. While their friends were having fun, they “had to hide away in this dark place and produce leaflets, leaflet bombs, and so on, and we had to lie a lot to our family and friends about where we disappeared to all the time and what were our political views. So they had the opposite impression of what we really were.”

You have to imagine, we were nicely brought up kids. We didn’t think about sticking money up our backside. It was the practicality of that sort of thing that was brought home to us by the book

He did such a good job of concealing his other life that when they were arrested, as the result of a police surveillance operation that closed in at 3am on 2 March 1978, after they were seen moving printing equipment between premises, his family “didn’t know what to believe”.

“Their political education hadn’t been advanced at all in this time, so they didn’t know we were doing this stuff. But they were the same parents that we had known, the same brothers and sisters, who had the same views we had before we started. They didn’t know how to cope with it. They didn’t believe it was happening.”

Nor could they immediately help their families to understand their viewpoint, as they were detained under Section Six of the Terrorism Act, giving the security police absolute power to hold them incommunicado, without access to lawyers or anyone else. “So all they knew was what they read in the newspapers. And the newspapers were propagating the point of view of the security police, which was saying these are bad guys, and they put bombs in the street, they’re terrorists, Communists, and they’re threatening the freedom of South Africa and inciting people to racial hatred.”

Lee tried to escape but was quickly apprehended. In the film, his character jumps out of a window wearing handcuffs. “I look at that,” he says groaning, “and I think, ‘I wish they hadn’t left them on, because it would have been ridiculous to try and escape like that!’”

In reality, he didn’t just decide to go on the spur of the moment. Rather, he twice faked illness to contrive visits to the doctor’s surgery, and having “sussed out” how he was going to get away on the first one, put his plan into action the second time. After leaping from a window, he unfortunately landed hard on his knee and was unable to recover before the security police had trained their guns on him. Though unsuccessful, “Stephen set a fine example that first day which set the tone for the future,” wrote Jenkin.

At a 31 March court appearance, a magistrate informed them that they were to be charged under Article 2(1) of the Terrorism Act of 1967 and Article 11(e) of the Internal Security Act of 1950 (formerly called the Suppression of Communism Act). In the meantime, they would be held at the massive Pollsmoor Prison while awaiting trial.

“The first time we were together again, we started to discuss how we were going to get out,” says Jenkin, “although we didn’t really have any plans at that stage.”

They took their first practical steps after Lee’s father gave him a copy of Papillon, Henri Charrière’s epic account of his escape from Devil’s Island, during his first visit. It was probably just meant as a humorous gift, but the comrades “interpreted it as a manual of escape,” says Jenkin, “that really set our minds on the escape project.”

A key lesson was that they would need money to get away as far as possible if they managed to break out of prison. Lee obtained R360, which they divided between them and stored in cigar tubes. Inspired by Papillon, they then hid the containers inside their rectums – something they’d probably never have thought of doing themselves.

We still struggled to understand why someone like Denis, who was a lifer, was not willing to come out with us

“You have to imagine, we were nicely brought up kids,” says Lee. “We didn’t think about sticking money up our backside. It was the practicality of that sort of thing that was brought home to us by the book. Once we’d read that we said, ‘OK, that’s a pretty good hint, that one. We’d better do that for a start.’”

On 15 June, Jenkin was sentenced to 12 years and Lee to eight. They were determined when they arrived in Pretoria, though, that they wouldn’t serve out their time. Unlike some of the seven other political prisoners already there, such as Denis Goldberg (played by Ian Hart in the film), who was sentenced with Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders in June 1964, they did not see themselves as prisoners of conscience, but as prisoners of war duty-bound to escape and carry on the fight.

“It wasn’t an ideological difference, it was a question of emotional identity of where we stood,” explains Lee. “But we still struggled to understand why someone like Denis, who was a lifer, was not willing to come out with us.”

“They kept saying, ‘It might feel pointless being in prison but we do serve a purpose by being here. The rest of the world knows that we’re here and that we’ve done something and we’re held up as examples,’” recalls Jenkin.

Although this was certainly true in the case of Mandela, he says they “couldn’t really buy into that story because we felt that most of us were minor prisoners, in a way, and after a while the world forgets you’re in there and it doesn’t really serve any constructive purpose. We felt being out of prison and continuing the struggle was a better way.”

But how to get out? They realised immediately upon arrival that any escape would have to begin with them getting out of their cells, which had an inner grille with a lock on the inside, and an outer door with a lock on the outside. “So there were straight away two doors we needed to unlock,” says Jenkin.

He decided he was going to make a key for the inner lock, whose dimensions he was able to work out from the lock itself. With Lee’s help, he made one out of the only material available to them: wood.

It felt “amazing” when it worked, but they knew that it was just the first step. They still needed to open the second door, which Jenkin ingeniously achieved by using a crank made from a broomstick and a block wood, which he could operate through a small window in his cell, to turn a key in the outside lock.

Now able to leave their cells, they thought about the next phase. For a while they considered violently overpowering and tying up the night guard whose keys they would use. As their intelligence increased, though, they discovered that he was also locked inside with them and could only get out when the day shift arrived. They would therefore need to make more keys for other doors.

Slowly and patiently they amassed their own set, as well as garnering clothes for up to eight escapees, and allowed the plan to form at its own pace as opening doors revealed new obstacles that needed to be overcome. Eventually they realised, seemingly counter-intuitively, that the least risky way to go out, was the same way they’d come in.

Their approach didn’t suit everyone, says Jenkin, and the escape team swelled and shrunk until just him, Lee and Moumbaris were left.

A lot of people think all we need to do is come up with a grand theory of how to solve humanity’s problems but you can’t work like that in reality

“I wouldn’t like to label us but the three of us who managed to get out were the pragmatic group and the others, I suppose, were the intellectuals. They got annoyed with us trying to open doors and make keys because they felt we were just endangering them and we’d get caught and everyone would suffer.

“Their approach was, ‘Why don’t we all just sit down and work out a plan to get out of this prison?’ We said, ‘No, it doesn’t work like that. Each time we open a door, things look different. So the plan has to evolve rather than just coming up with a blueprint that demanded you follow.’”

The experience has shaped the way he sees the world. Today, he views it as a giant prison where problems such as “climate disruption” and debt slavery (an issue he has been addressing as part of the alternative currency movement) are like the locks to which we need to find the keys.

Everything can't be done in one go, he says: “A lot of people think all we need to do is come up with a grand theory of how to solve humanity's problems or have a revolution imposing Utopia on humanity, a new economical social system, but you can't work like that in reality. You open one door on one problem and then try to tackle the next one, because you don't know what's beyond the next one.”

Finally, I ask each of them if the South Africa that emerged after the ANC took power was the one that they’d envisaged as young men. “Ultimately not really, no,” says Jenkin. “We all had very high hopes at the beginning, but I guess we were all pretty naïve about things and it soon became clear to us that all we’d achieved was a sort of political victory, and the ANC was not really in control . . . It’s still hugely unequal. The structures that were created by apartheid are still there ... Many people are saying things are even worse today, but I wouldn’t like to say anything like that.”

Lee agrees: “Clearly the present South Africa is not implementing the ideals of the Freedom Charter that we believed in so passionately. That’s just a matter of how history goes . . . The economic legacy of apartheid and the political structure of the country is largely unchanged. I personally feel quite bitter about that. I imagine there are lots of people who are. I don’t understand why some of my former comrades are not fighting harder for the ideals we stood for.”

For South Africa, it seems, the past is harder to escape than a prison.

‘Escape from Pretoria’ is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments