The power of political cartoons

They draw attention to corruption, hold power to account and poke fun at the dictators and the despots. In the age of larger-than-life leaders and the internet echo chamber, political cartoons seem more poignant than ever. Zoe Ettinger speaks to six illustrators about their best – and worst – creations

A wry smile. A knowing stare. The unique tuft of hair on Donald Trump’s head. These characteristics come to life when they are expressed visually. In other words, some things have to be seen to be believed. Cartoonists and caricaturists capitalise on this fact, and capture audiences with their unique renditions of people we know and instantly recognise.

Cartoon and caricature date back to the 15th century. Leonardo da Vinci was known for creating exaggerated drawings of townspeople. These doodles were actually some of his most popular works at the time, their humour appealing to a wider audience.

Unlike the traditional Mona Lisa or Salvator Mundi, these drawings sought out unconventional-looking people, those with big bumpy noses or protruding chins, and made them even more pronounced. It was through this expansion of the human form that Leonardo was able to comment on the multifaceted nature of man. It was as if he could transpose their personality directly onto the page.

Following Leonardo, other artists chose to use caricature for political comment. Widely viewed as the father of political cartoon, James Gillray created satirical drawings of King George III in the 18th century, depicting him in various works as a glutinous fat man and bumbling idiot.

Previously, such seditious artwork would have been grounds for arrest (or possibly even execution), but Gillray worked in the first fruitful time for such liberal political commentary; George III was not a well-liked monarch, and society was beginning to question his ability to rule after losing control of the colonies. In addition, Gillray’s cartoons were regarded as works of art, further promoting his credibility and bolstering his political stance.

The mid-1800s saw the rise of the illustrated magazine. These periodicals were started in France and Britain and focused on humorous content. The most famous of these was Punch – the magazine actually introduced the term “cartoon” in 1843. John Tenniel, its chief cartoonist, used his drawings to comment on the relationship between Britain and Ireland, particularly the acquisition of Irish lands.

Not long after Punch, many newspapers started using cartoon to express political opinions. In the United States, Thomas Nast of Harper’s Weekly drew to comment on issues like slavery, the Civil War and corruption. He is credited with creating the image of the donkey to represent the Democratic Party and the elephant for the Republicans.

By the 20th century, cartoons had garnered their own section in newspapers. They were still used to poke fun, but their ability to enact social change became cemented. In 1922, the first Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning was awarded to Rollin Kirby for his work “On the Road to Moscow”, which depicted the grim reaper leading victims of the Russian famine in 1921. This poignant image showed the world something they were not seeing; it exposed hidden suffering in a way that words could not.

Kirby would go on to win the prize two more times, both for works commenting on highly publicised political issues of the time, including Second World War propaganda and commentary on the Zimmerman Telegram. Kirby was able to capture a widespread view on the explosive nature of war and the dangers it inflicted upon society.

Today, nearly all news publications have sections devoted to caricature and cartoon, and more than ever we need its light-hearted yet powerful commentary on an ever more divisive society, where power lies in the hands of volatile and even dangerous leaders.

To examine the current state of affairs in the world of cartooning, I spoke to five artists, ranging from an apolitical social caricaturist to an ultra-conservative political cartoonist, to get their take on how they use art to express opinion.

Dave Brown, The Independent

Our resident cartoonist, Dave Brown, has been creating works for the past 25 years. Through unapologetic and unmerciful illustrations, he awakens audiences to the issues of the day.

Initially a painter, Brown didn’t exactly have plans to become a cartoonist. He went to art school, but when his paintings began to take up more of his tiny bedsit than he was, he realised: “I need to create smaller works.” And that’s how Brown got started cartooning. He entered one of his early works into a contest and won, which helped him land his first cartooning job at The Sunday Times.

Brown’s cartoons are quintessentially British, ready to take a jab at any politician who needs it, particularly Donald Trump. Brown says he thinks the difference between British and American cartoonists is how they react to those in power. “It’s funny that the British are viewed as more polite, but really in America there is a sort of politesse and deference to power that we don’t have in the UK,” he says. After all, James Gillray became the father of political cartooning from his illustrations of King George. “It’s more ingrained in the system,” Brown says.

Yet even in a climate that welcomes critiques of power, Brown has faced harsh criticism and has even received death threats. His most famous cartoon, called “Monster Eating Palestinian Babies”, stirred the most controversy. It depicts former Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon as the monster, for his role in the deaths of Palestinian women and children. The cartoon is an allusion to Spanish romantic painter Francisco de Goya’s work, “Saturn Devouring His Son”, in which Saturn, fearing one of his children will overthrow him, devours it.

Brown’s depiction of Sharon was misconstrued by many to be an attack on the Jewish community, and led to Independent phone lines crashing with complaints. Yet the work was simply meant as a criticism of Sharon, and bore no ill will towards the Jewish community at large. The piece went on to win the 2003 Cartoon of the Year award, which he said was bittersweet, as it created an entirely new round of backlash by those who believed it didn’t deserve to win.

A cartoon must be rooted in truth, but needs a certain level of offence, Brown says. In terms of where to draw that line, he references journalism legend Finley Peter Dunne, who once said newspapers should “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted”.

Brown’s view on cartoons is nicely summed up in his latest Voices piece: “Increasingly people seem to believe they have a right not to be offended, and that anything that more than one person finds offensive should be censored, banned, grovellingly apologised for, and the culprit is fired. I, on the other hand, believe everybody should be offended at least once a day, preferably by one of my cartoons.”

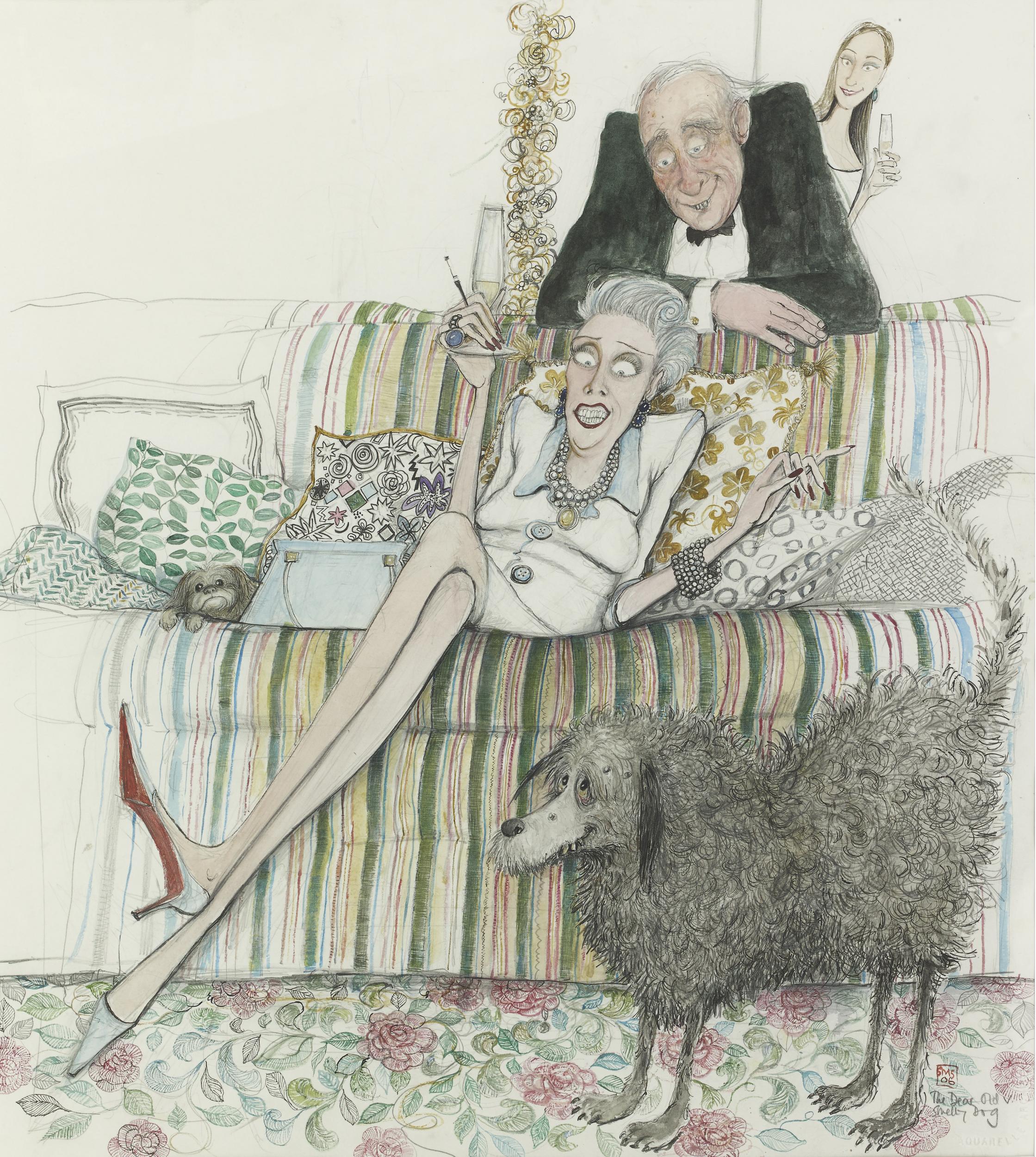

Sue Macartney-Snape, apolitical social caricaturist

Macartney-Snape is a Tanzanian-born caricaturist who came to London in the mid-1980s to exhibit her work. After living in Melbourne most of her life, she found herself inspired by many of the upper-echelon characters on London’s streets. “Coming from Australia, I believe it gave me some great advantage as an outsider.”

When I first came to England in the 1980s, there were more eccentrics around. People didn’t fix themselves, and they didn’t look as perfect as they do today. Now people are so much more self-conscious. Age gives people character, faces become more interesting to draw

She remarked on how, back then, it used to be easier to create such drawings: “When I first came to England in the 1980s, there were more eccentrics around. People didn’t fix themselves, and they didn’t look as perfect as they do today. Now people are so much more self-conscious.”

Modern society is seeing an erasure of many unique facial characteristics. Veneers have become increasingly popular, letting the British caricature of crooked teeth finally fade into memory. Additionally, procedures like botox and fillers have changed the way our faces age. As Snape says: “Age gives people character, faces become more interesting to draw.”

To Snape, the most important part of caricature is to make people laugh. “I think laughter is so important. My mother came to one of my exhibitions and she said, ‘people are just going around laughing’ and I think that’s brilliant.” Snape also wants to make people think differently, saying that “I think some of my better caricatures do that”.

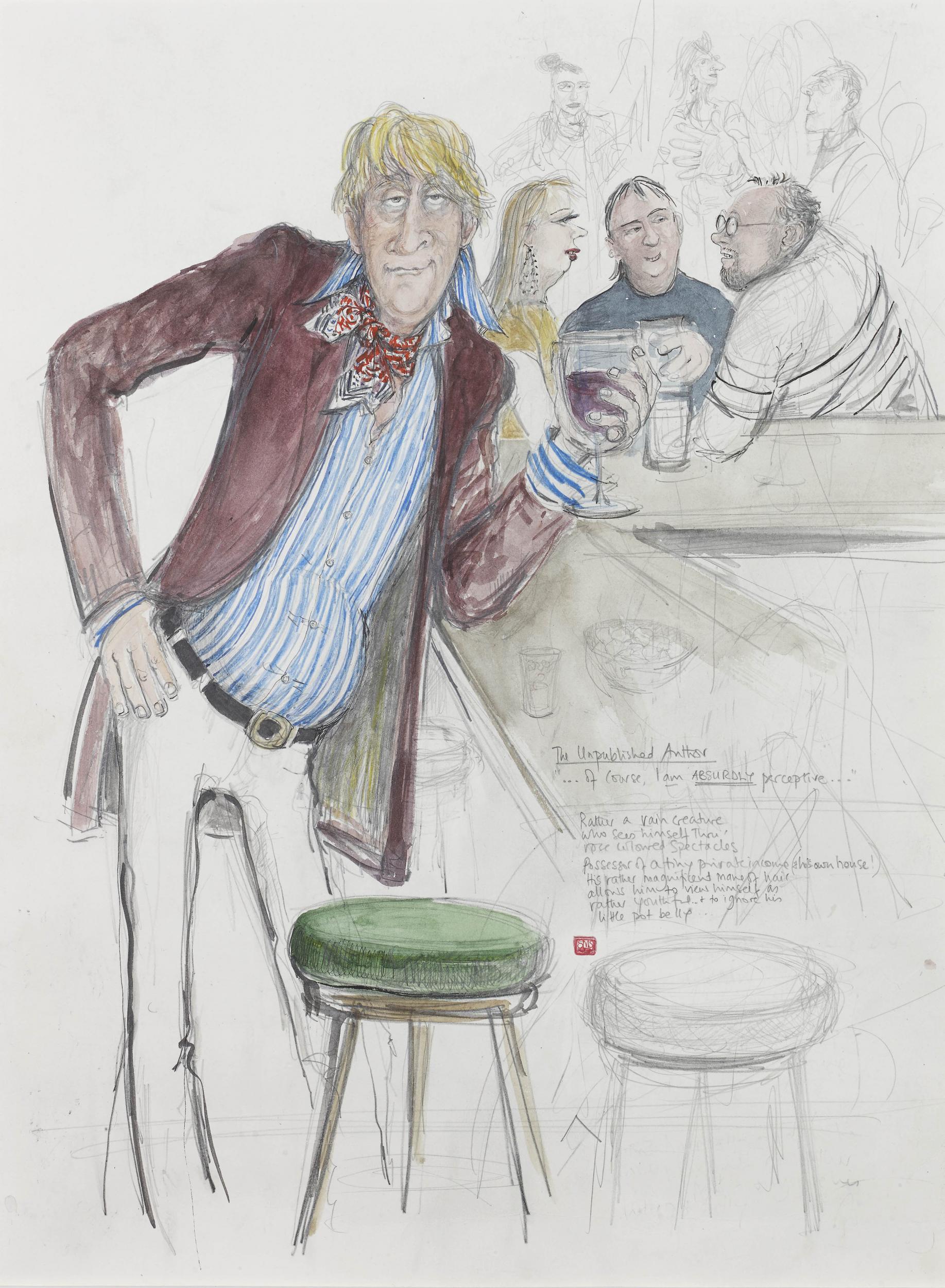

One in particular that caught my eye at her exhibition at the Panter and Hall gallery in St James’s was “The Unpublished Author”, with his smug face and rotund belly. Somehow he’s instantly recognisable, and though the work was created decades ago, it still resonates today.

Caricatures like Macartney-Snape’s capitalise on unspoken language. They take it, stretch it out and show it to us. The woman who looks the spitting image of her dog. The haughty couple on the way to the ball. It’s the personification of a side glance between friends.

The best caricaturists are able to draw people as if they have known them for years. At her first exhibition in London, full of grand people, a woman stopped her. “My god she was incredible – very tall, red hair (you know redheads can go very elegant) and she came up to me and said: ‘My dear, how do you know so much about us?’”

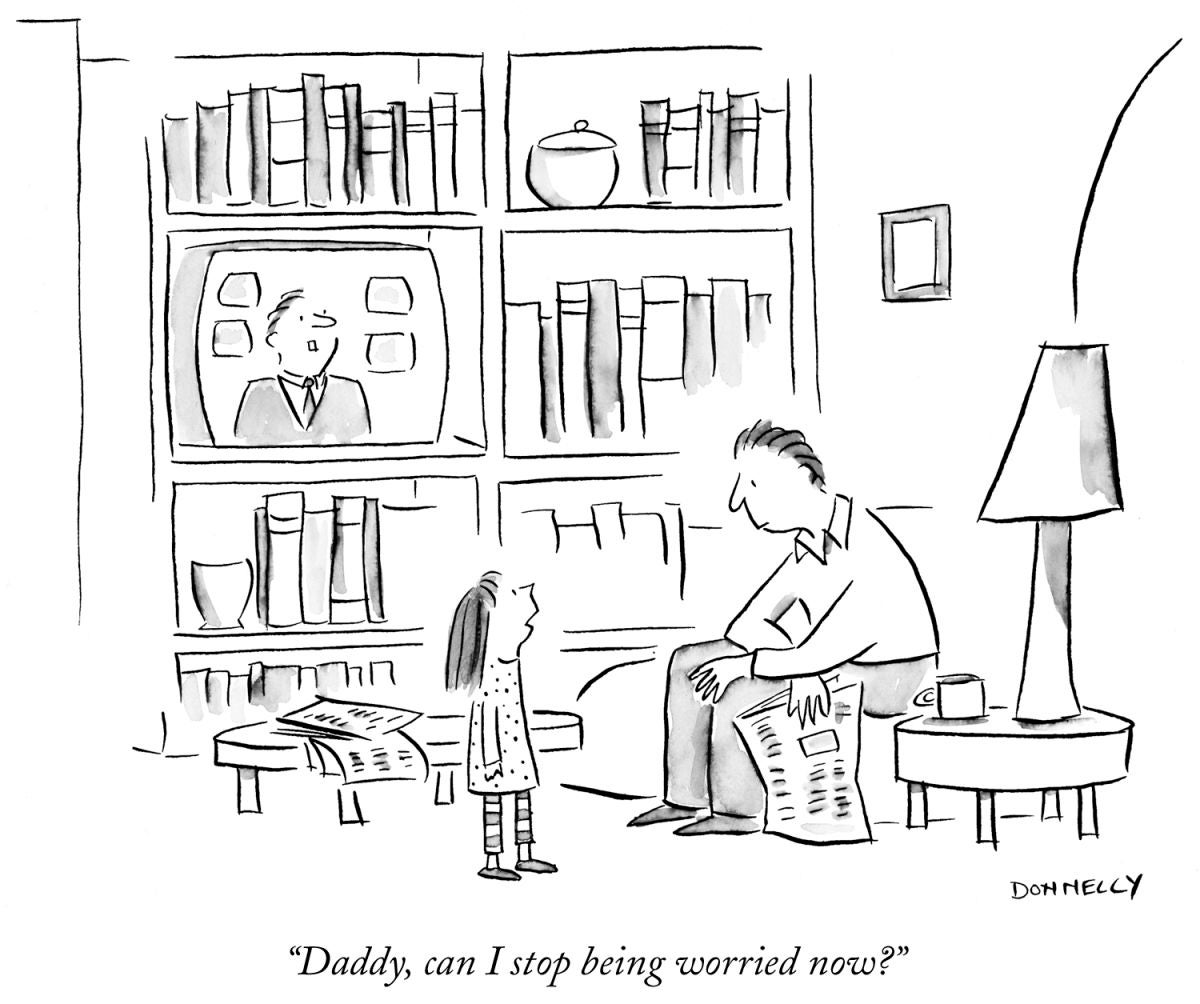

Liza Donnelly, New Yorker and Medium political and social cartoonist

Donnelly, based in New York City, is an artist known for her “slice of life” cartoons, where she examines the intricacies of day-to-day life and relationships. She sold her first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1979, where she was one of only three female cartoonists at the time. She continues to be featured in the magazine, as well as on Medium and CBS News.

Donnelly has a unique style, composed of short, purposeful linework often in black and white. She describes her work as more observational than opinionated; a quiet commentary. “I don’t like to make fun of people. I try to do cartoons more about the big picture than ridiculing individuals.”

That was what initially drew her to The New Yorker, well known for nuanced, rather than overt, political commentary. Through symbols like the Statue of Liberty and the American flag, she’s been able to illustrate universal representations of America and use them to express opinions on current issues from gun control to elections.

With such serious issues to tackle, it seems like cartoon may not be the best medium for comment. However, Donnelly shows it doesn’t always have to be poking fun; in fact, it can aptly capture poignant moments.

For example, after 9/11, Donnelly said she wasn’t sure how to be a cartoonist anymore. “I questioned what I was doing as a career and whether it was something I wanted to continue doing. I’d been doing most light-hearted life cartoons for The New Yorker.”

The tragedy marked a turning point for her – she submitted a piece to The New Yorker, a mild, uncomplicated image of a young girl in front of a television, asking her father, “Daddy can I stop being worried now?”. This humble yet powerful piece captured the national sentiment of the time – that we were under attack, and when, if ever, it was going to stop.

Since then, Donnelly has continued to create political cartoons, commenting on everything from Trump to women’s rights. Though it may seem like Trump would be a cartoonist’s dream, Donnelly sees things differently: “I think at first he was easy to caricature, but after a while, how often can you just make fun of a man. What good does that do? Just making fun of a person constantly, not only is it meaningless, ultimately it just perpetuates the divisiveness of it.” She wants her work to spark conversation. A funny cartoon on feminism may push a reader who would be otherwise uninterested to research the topic further.

At what point do you decide what you do and do not consume based on your political opinions? If you order a burger, do you know if that farmer was a Trump supporter? What about the chair you’re sitting on, who did the person who made that vote for?

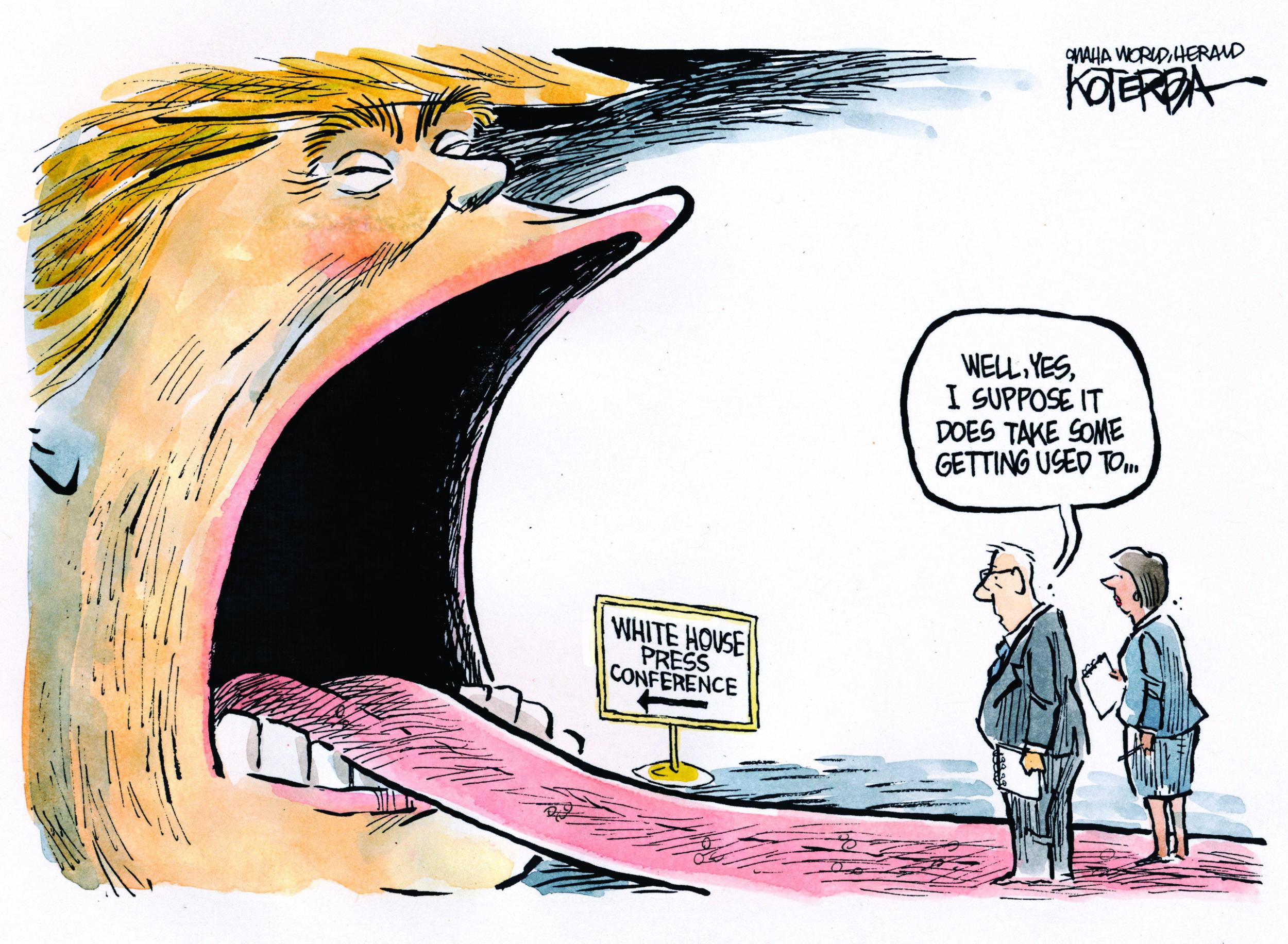

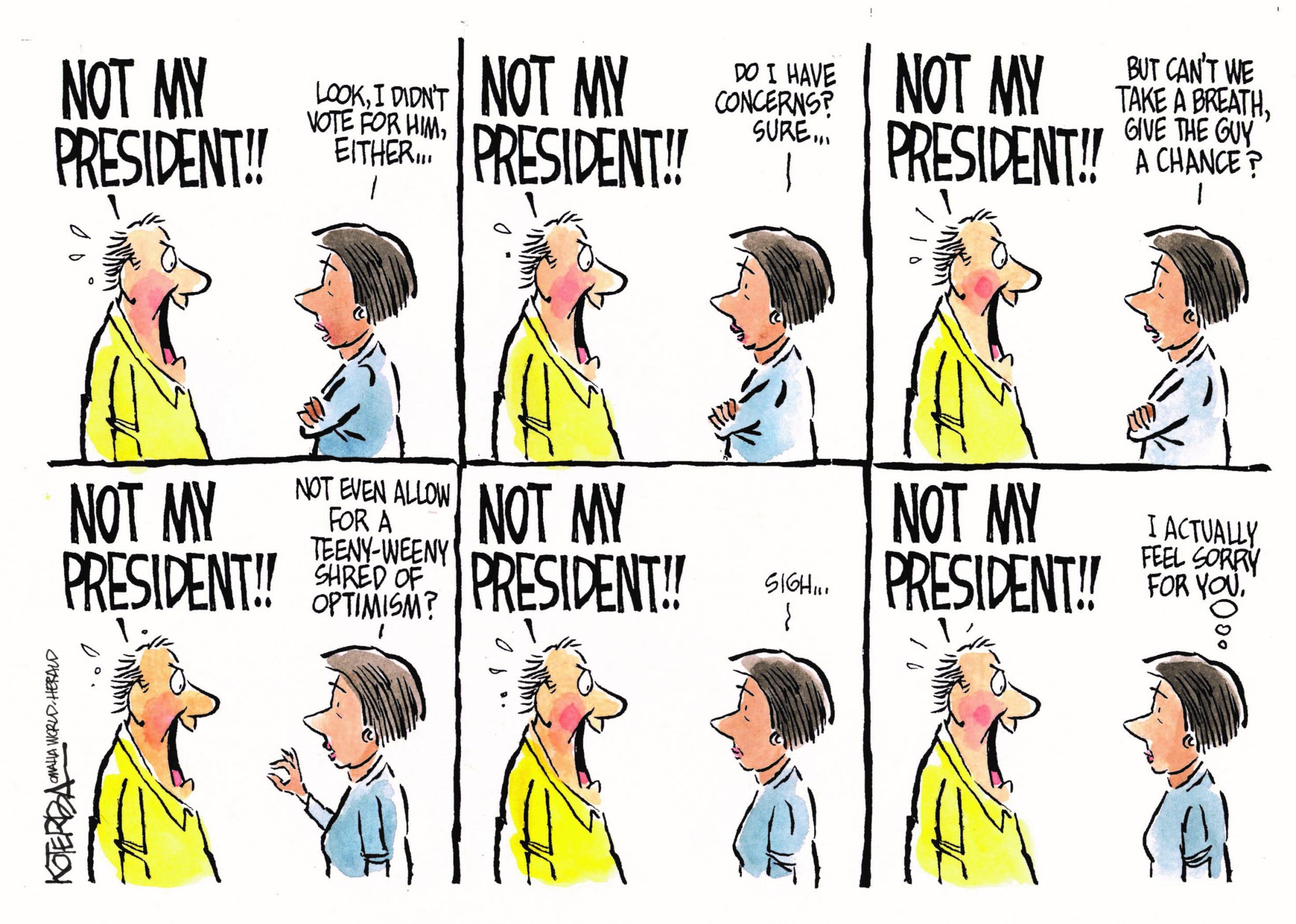

Jeffrey Koterba, New York Times, Washington Post and Omaha World Herald political cartoonist

Koterba is a Nebraskan cartoonist living and working in Omaha. He describes himself as a passionate centrist, and remarks that people often muddle the term centrist – believing it to be someone who doesn’t want to take sides, haphazardly straddling the fence. Rather, he firmly believes that truth is never entirely on one side or another, and, more than anything, has been exhausted by all the extremism.

Though his work takes on current affairs in politics, he doesn’t describe himself as a political insider. “Lots of friends of mine live, eat and breathe politics. I can’t stand it. But I think that may make me a better commentator.” Through putting space between himself and that realm, he’s able to poke fun in a way that appeals to his readers, who, for the most part, have no connection to politics.

He describes certain other cartoonists, likely those with more extreme political views, as “bomb throwers”: putting out work that is meant to cause a stir and stands firmly on either the left or the right.

Koterba’s cartoons take a different approach: “I don’t know if it’s because I’ve been doing this a while or because I’ve gotten older or because of this divided climate we’re living in but I find myself drawing more cartoons about our common humanity and what brings us together.”

“Can’t we all just get along?” might not be the sexiest political sentiment, but in the current surroundings, with such venom on each side for the other, perhaps we need more voices proposing such civility.

Koterba has seen such divisiveness firsthand. One day, sitting at a local cafe in Omaha, he saw a man wearing a Maga hat come in and attempt to order a drink. The man was refused service because of his hat.

I don’t know if it’s because I’ve been doing this a while or because I’ve gotten older or because of this divided climate were living in but I find myself drawing more cartoons about our common humanity and what brings us together

Koterba thought it posed an interesting quandary: “At what point do you decide what you do and do not consume based on your political opinions? If you order a burger, do you know if that farmer was a Trump supporter? What about the chair you’re sitting on, who did the person who made that vote for?” In reality, it’s impossible to entirely segregate yourself from differing political opinions, and though you may make a statement by refusing someone with a Maga hat, what good does it really do?

One of Koterba’s cartoons caused quite a stir – not for what it said, but for how it was construed. That’s the magic and trouble with illustration: it’s left open to interpretation. In the image below, he’s commenting on Trump’s inauguration, saying “Let’s just take a breath”. This was immediately taken as pro-Trump, and he received “angry, vile, nasty messages”.

Even before his inauguration, not being publicly anti-Trump has equated to being pro-Trump. The phenomenon of the internet echo chamber is something opinion cartoonists must, too, grapple with each time they publish.

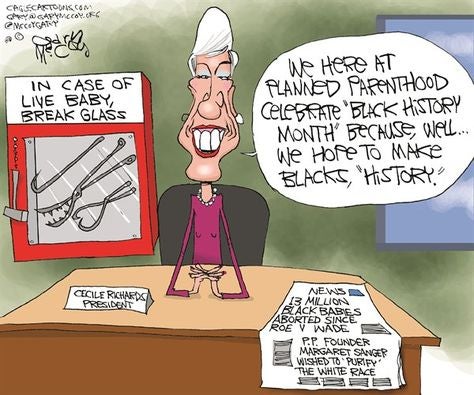

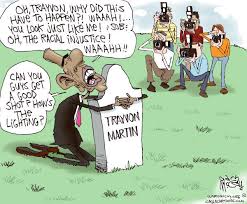

Gary McCoy, The Flying McCoys, Politico, Playboy

McCoy, from Illinois, was the only conservative cartoonist I spoke to for this piece. There simply aren’t as many of them, and some of their work, including McCoy’s, is not only incendiary, but can be seen as quite offensive.

McCoy says his right-wing leanings started from an early age. “My conservative principles, instilled in me by my parents, and reinforced by my grade school education, only solidified once I found the voice to express them.” The cartoonist went to Catholic school and suffered from severe depression at high school. He says: “I came out of it transformed from the shy kid I was to a radical, outspoken provocateur.”

Provocateur is putting it lightly. His anti-abortion cartoons include the Statue of Liberty holding bloody forceps and mass aborted baby graves. He even has one with Cecile Richards, former president of Planned Parenthood, sitting in front of a case of sharp metal tools with the sign: “In case of live baby, break glass.”

Yet something to remember is that McCoy is trying to cause a stir; he wants to affect change in society in line with his views. An “unapologetic conservative”, he says he has a responsibility to get his stance out there. “I believe there’s a market for views like mine that don’t straddle the fence.” They certainly don’t, but their shocking nature can serve to promote the divisiveness he’s trying to bridge.

This one below, of Obama pretending to cry for a photo op over the grave of murdered teen Trayvon Martin is a good example.

What makes a man want to comment on abortion? McCoy says his religious beliefs helped him form his pro-life views, though he claims to never use religion as a pro-life defence in his cartoons. He says he approaches it “as a moral and human rights issue”, and that he feels “so strongly in the protection of unborn human life”.

As for the comic that gave him a bad name, he says it was one of Georgetown student Sandra Fluke, who testified in front of Congress about contraception and abortion rights. As McCoy says, he was – perhaps – “too incendiary in how I portrayed miss Fluke. Both visually and content-wise.”

McCoy’s cartoons show visually what his conservative literary counterparts write – explosive opinion, unapologetically expressed.

Brian Adcock, The Independent

Our very own cartoonist Brian Adcock has been working for The Independent for the past eight years producing colourful, detailed caricatures of political leaders worldwide.

Inspired by comics as a child, Adcock has been cartooning nearly his whole life. He drew inspiration from artists like Gary Larson of The Far Side and Ralph Steadman, who illustrated Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

He got his start publishing cartoons in Punch magazine, the one started back in 1843. After that, he took time off to become a “rubbish musician”, though he says that never really worked out. He then went back to cartooning, initially planning to be a gag cartoonist – producing simple, single-panel comics meant to simply draw a laugh.

However, after going to Prague on holiday, he wound up meeting his wife and moving there. He then took a job at The Prague Post, where he began political cartooning. At the time, the Czech Republic was new to democracy, just 10 years on from the fall of the Berlin Wall, and was shifting from communism to capitalism. “I just sort of fell into politics at that point,” he says. The culture was ripe for comment.

After moving back to England, Adcock took his political commentary to The Independent, where he says that his cartoons and others bring an immediacy and impact that the written word cannot.

Though some cartoonists like to leave their work open to interpretation, Adcock likes to take a more direct approach, especially when it comes to his depictions of Trump: “What I’ve learnt is, it’s all well and good being clever and multi-layered, but really the ones that the broader public get are those immediate ones.” He likes to make his Trumps as eye-catching as possible, exaggerating his hair, ties and ridiculous ego, with uncomplicated messages to go alongside.

Like anyone expressing an opinion, Adcock has faced backlash. A piece he did on Jeremy Corbyn for The Guardian depicted the MP staddling two bins, one recycling and one general rubbish, saying: “They can’t decide which one I should go in.” Much like Koterba’s Trump cartoon, Adcock’s work was immediately viewed as anti-Corbyn – though he expresses that was not the intent. “All it was saying is, are the labour party going to continue with Corbynism or not?”

That nuance was lost, and Adcock found himself having to defend the image online. Cartoon opinions often function like headlines, where many will read them once and decide they know what the entire article is going to be about. This issue, predictably, is only more prevalent in cartoons that comment on leaders like Corbyn or Trump, who have such strong supporters on one side and opponents on the other, that offending either one opens you up to extreme scrutiny… and often unwarranted abuse.

Cartooning today is a dangerous game. The internet has made it possible for people to condemn anyone they want, and to gather a sizable crowd while doing so. It’s the same for any type of opinion journalism – when you choose a side you’re going to face opposition. The question is: do we want to throw stones at the other blindly, or turn and look at them, and perhaps see something we missed the first time?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments