The Other Side of the River: The reality of the Kurdish women’s movement in Rojava

Stephen Applebaum speaks to Antonia Kilian about the making of her film, ‘The Other Side of the River’, which explores an autonomous territory in northeastern Syria that spawned a feminist revolution

The Kurdish liberation of the Isis-held city of Minbij, in northern Syria, in 2016, was just the kind of event that the German filmmaker Antonia Kilian needed to happen to spur her on. Since 2015, she had been planning to explore first-hand the reality of the Kurdish women's movement in Rojava – a de facto autonomous territory in northeastern Syria that spawned a feminist revolution – but did not know how to navigate the “embargo” then in place on people entering the region.

“Step by step I was preparing,” she tells me from home, “but I had no idea if I would be successful. I heard stories of people who had managed to cross, but it was not clear for me.”

Nevertheless, as she sat in a Berlin apartment watching a TV news report showing women throwing off their black burkas, revealing colourful clothes underneath, as they ran towards female fighters who had helped to end Isis’s three-year rule, she knew it was the moment. So began a journey that led to The Other Side of the River, an eye-opening, intimate and beautifully shot film set on both sides of the Euphrates that is currently playing in international film festivals.

Surrounded by strong, independent women from a young age, Kilian’s path to Rojava was effectively being laid years before she started thinking about making the documentary. Her mother and aunties “were part of 1968, or a bit later, and the women’s movement in Germany”, she says. “So I grew up with an idea of what feminism could be, and with this sense of organising as a woman.”

She remembers her mother taking her to the International Women’s Day celebration in her hometown, “which back then was mainly organised by the Kurdish women’s movement”, says Kilian. “So already, as a small child, I somehow knew that Kurdish women can be quite feminist.”

Kilian started taking a more in-depth interest in Syria around the time of the resistance against Isis in Kobane in 2014, while simultaneously following the “big social movements” that were occurring in Turkey. She joined solidarity groups, took part in protests, read books about feminism in Rojava, and travelled back and forth to Kurdish areas in Turkey as an election observer.

“Slowly, slowly I got more deeply involved from a more activist perspective, which ultimately led to the wish to understand more and better the political and social situation, and to somehow learn from it, witness it, as this historical moment.”

Her entry was only possible with permission from the Kurdish women’s movement. Inside Rojava, too, they controlled who crossed checkpoints, and who could film

She became fascinated by Minbij, which had been one of the first cities to rise up against Assad and therefore had its own “experience of revolution that is not connected to Rojava”. This was the first time the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) had taken control of a “largely Arab populated city”, says Kilian. She thought that if she could get in, she “could document the process of bringing their revolutionary political system and the idea of women’s liberation to a city that was ruled for three years by Isis, but also wasn’t a stronghold of the Kurdish movement because it is on the other side of the Euphrates, outside of the Kurdish core territory.”

Kilian appealed to the women's diplomacy office in Qamlishi, on the Syrian side of the Syria-Turkey border, for help, but was refused support because of the embargo. Unwilling to give up, she accompanied a Syrian filmmaker living in Germany to the Duhok International Film Festival (“I asked him, ‘Can I just come with you so I’m closer to the border and will figure out from there how to cross?’”), and approached the women’s diplomacy office in Kurdistan Iraq.

“My friend won a prize at this festival, so he was in the news on that day, and I gave a speech to the woman in the office about how much I wanted to enter northeast Syria and make this film about the women’s revolution. I think they liked it because they said, ‘Okay, in two weeks we can bring you in,’ which I wasn’t really prepared for. I had my camera with me, but I didn't really think that it would work out. So I waited for two weeks, and then I was inside.”

Her entry was only possible with permission from the Kurdish women’s movement. Inside Rojava, too, they controlled who crossed checkpoints, and who could film.

“You had to be approved by them and it was clear that they only let you in so you learn from them. So it’s a kind of agreement,” says Kilian. “They set the rules to some extent, at least in the beginning, and said, ‘Maybe you have this idea to export your feminism, but no: we help you grow as a feminist so you get stronger in your country and can support us, because this will help the worldwide revolution to spread’.”

Kilian stayed for a year (then returned for an additional month’s filming) and was able to dig deep and wide. However, it isn’t difficult to see how the independence and judgement of a documentary maker who didn’t spend as long as her engaging with people in different spheres of the region’s social and political life could be used for propaganda. For this reason, Kilian is “very open” about the conditions under which she arrived in Rojava. “I went,” she says, “like many westerners who ended up there, full of admiration and with these big eyes, wanting to learn, full of solidarity, and thinking, ‘We will now witness the most important revolutionary moment of the century’, comparing it to the Paris Commune, and full of all this hope for something extraordinary to happen.”

She admits to “knowing nothing, or just a very little bit” at the beginning, and believes the relationships she formed with three people in particular – Sevinaz Evdike, the Kurdish Syrian co-head of a film collective called Rojava Film Commune, who was recently seen in Alba Sotorra’s documentary The Return: Life After Isis; Arash Asadi, an exiled Iranian journalist/filmmaker (now also Killian’s husband), and Guevara Namer, a Kurdish Syrian filmmaker based in Germany, who are both credited as co-authors of The Other Side of the River – enabled her to move away from a primarily ideological approach influenced by her book reading, and have the kind of “reality check … which, maybe, a lot of people from the west going there don’t really experience.”

At first, her plan to go to Minbij after crossing the border was blocked by women commanders, who told her it was too dangerous: she was alone and they had only just taken over the city. For the moment she would need to stay in the core territory of Rojava, they said, closer to the border of Kurdistan Iraq.

“It was really Minbij that had attracted me,” says the director, “and it was not like I came there and I have my camera, and I speak the language [she needed to find translators], and I can just start working. I was in a very, very, let’s say weak position. So I needed to find a way where I can do something where I feel I can somehow go deeper.”

Put up in the home of Evdike and her family, Kilian started meeting women in different walks of life, including military and civilian. She had only planned to stay for a few weeks, but then she met Hala Mustafa, a charismatic 19-year-old Arab recruit at a police training academy, and everything changed.

Hala had only been at the military school for two weeks, having run away from her Isis-supporting family in Minbij with her sister, Sosan, following the liberation of the city, but exuded a confidence and ease that made it seem like she had been there longer. Opinionated and outspoken, moody, unpredictable, compassionate, and by turns fiery and vulnerable, she was the first woman Kilian spoke to at the academy “who urgently wanted to be filmed, and the first one I felt also urgently wanted to share her story, and somehow was flirting heavily with me and the camera”.

Rojava gives women hope and opportunity, and puts them on an equal footing with men, in the military, politics, and at the head of organisations

In a society where women lack power, Hala and her sister had been forced into engagements by their father, the former with the son of his business partner, the latter with an Isis fighter. Hala railed against her situation, and was beaten for her defiance. Now feeling betrayed by the man who was supposed to care for her, and who tells Kilian that he could deal with his errant daughter with one bullet, she has lost all trust in men. “I don’t need a man,” she tells comrades in the film. “Everything we've suffered has been because of men … Who’s going to protect you if the father who raised you won’t?”

For Hala, joining the police, or Asayish, was a way to protect her honour, and became a means by which to pursue a plan (as yet unfulfilled) to liberate younger sisters she left behind when she ran away. Her family, though, feel they’ve been shamed. When I mention a news story to Kilian from August about a member of the Women's Protection Units (YPJ) who was murdered by her own brother in the Syrian town of Darbasiyyah, in an honour killing, she isn’t surprised.

“I think a woman always lives with the threat of not knowing what will happen to you if you disrespect the honour of the family or behave in a way that they say disrespects their honour,” she says. “There were always threats from the family to kidnap Hala and take her back home, and you never know what then will happen. A lot of honour killings are happening in the area and we were, of course, afraid that this would happen, and Hala was herself afraid.”

In their family’s and society’s eyes, Hala and Sosan, who had joined the police together and then been sent to different military academies, had committed a number of transgressions.

“First, you’re going away from the family home as a woman and you don’t live on your own in a city like Minbij without a husband,” explains Kilian. “Then, you're joining the enemy and returning to your city as one of the occupier’s force, because for the family the Kurdish are the occupiers of the city, and you’re holding your gun against the society, from their perspective. So I think there’s a lot of reasons to say you’ve dishonoured the family. Like many more reasons, maybe, than other honour killings have as a basis.”

Kilian followed Hala’s life at the academy with almost unfettered access, and was surprised by some of the things they allowed her to film. As well as documenting activities on the training ground, and interactions between the recruits in their downtime, she goes inside the classroom and observes them being lectured about “the reality of men” by a steely officer, who tells them “marriage is an instrument for suffocating women” and she will only feel free when “every single woman in the Middle East and everywhere else is liberated”. On another occasion, a woman warns them that “sexual desire leads to the abyss”, and they must push aside theirs in order to focus on the revolutionary path. Is it all an extreme reaction to an extreme situation? I ask Killian.

“That is the big question: is it just an extreme reaction to an extreme situation or is it to some extent also reactionary thinking?”

While she believes they’re “proud of this approach”, which she suggests could partly explain their willingness to allow her camera in, “when it comes to sexual liberation, and all the questions around partnerships and sexuality, for me it’s not a very progressive approach,” she says. “So, while I don’t want to question the necessity of taking up arms or joining a military force, when it comes to who decides what to do with your own body, I’m very sensitive … As a woman, I think what a woman does with their body is their choice.”

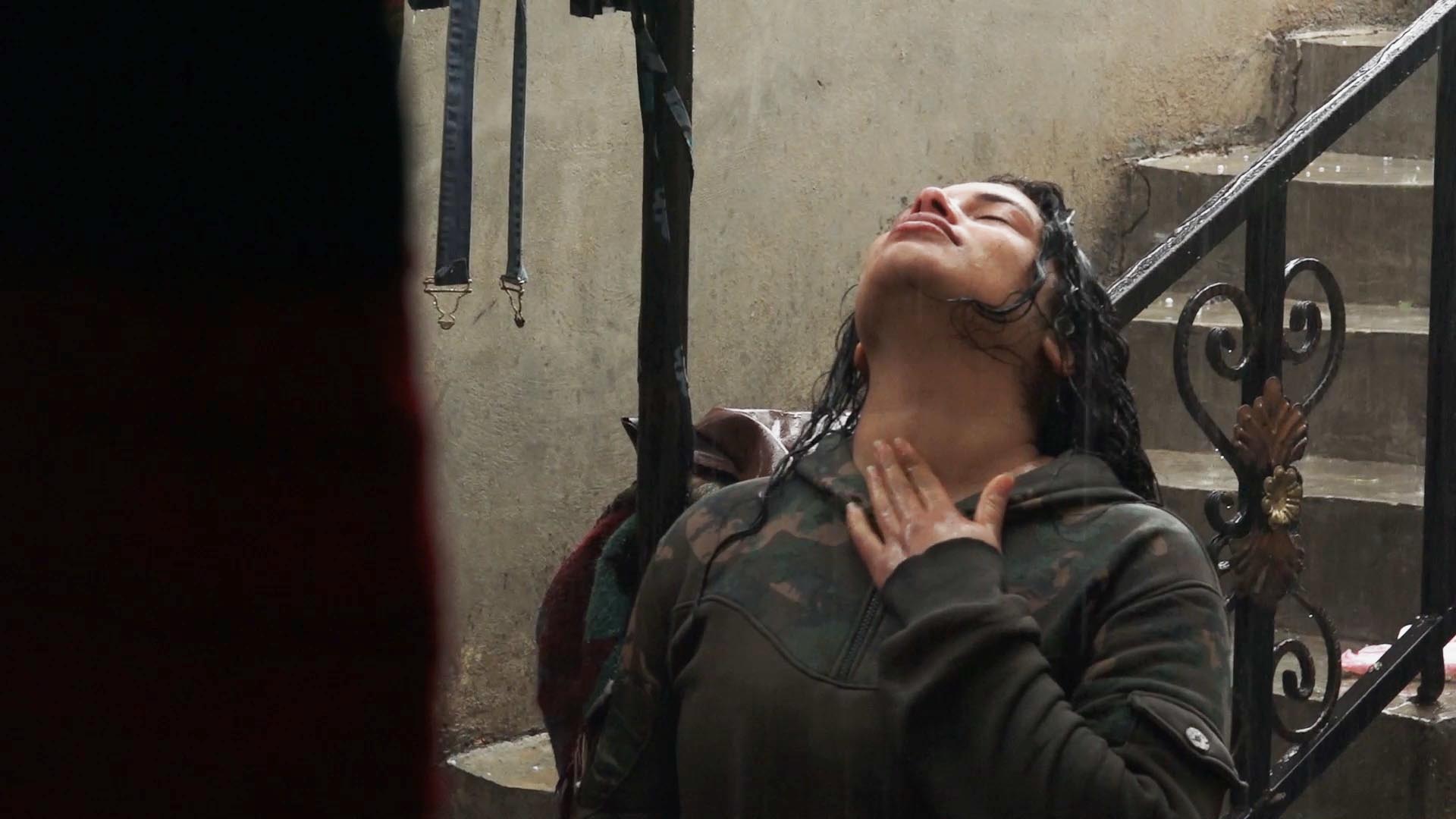

Arms give women a feeling of protection and control. While at the academy, though, Kilian became keenly aware of the damage that had been done by the ongoing conflict in Syria and, in some areas, years of Isis oppression and violence. At times, Hala, who recalls being ordered out of her house to watch a mother be stoned to death, seems to withdraw into herself, and there is an underlying melancholy to her spirited character.

Kilian says she had arrived from Germany “having this idea of revolution and all its glory and victory”, but, in the first of her reality checks, realised “it’s a war zone, and people are tired and exhausted and heavily traumatised. Of course, it gets worse with the people who experienced the Islamic State for such a long time.”

Signs of trauma were everywhere. “You can recognise this in the eyes of the people and their behaviour, and, of course, in the stories they tell,” she says. At the academy, women would break down, cry in the night, and fall unconscious. This kind of psychological and emotional damage also took on a topographical form when Kilian was finally able to cross the Euphrates and enter the war-torn heart of Minbij, after Hala was posted to the city following her graduation.

In the film it appears she joined Hala immediately. In fact, it took two months, because of fears over her safety. In the meantime, Kilian worked with Evdike giving filmmaking workshops to young women, and produced three short films – one protesting violence against women, one against having multiple marriages, and one against underage marriage – which, she says, are still being broadcast by Kurdish TV.

“They realised I wouldn’t go back home and that I am extremely stubborn, and I think all this [work] convinced the women’s movement and the women’s commanders to give me the permission to travel to Minbij.”

We see a city recovering from war, and still marked by tell-tale signs of Isis’s recent presence. Kilian vividly recalls entering it for the first time, in a police car from Kobane, alone and without a translator. “I was scared, because I realised that the whole atmosphere was really different from what I had experienced so far on the other side of the river.”

At the police station, Hala listens to women’s allegations of domestic violence, advises victims of their rights under the new regime, and sends out all-female units to make arrests

She was now outside the core territory of Rojava, and most of the women she saw were wearing a head scarf or full burka. “It was as if Isis had just left,” she says.

“On many walls you could still see the Isis paintings, in black and white, and on the main square there were still the metal grids where they had tortured and beheaded people. The prison in the former government building that was run by Isis was still there, full of their torture equipment, and it was dangerous to walk in many areas because of remaining mines.”

Kilian came under the protection of Hala’s commander, Eylem, and often slept at the police station where her young subject lived (until she was able to afford her own flat) and worked. In Rojava she had been able to move around freely, but in Minbij, at first, she couldn't go out on the streets without a police escort.

“In the police station where I lived was also a prison that was full of Isis prisoners,” she says. “It was strange, because once a week they were allowed to walk in the yard where we filmed a lot.

“Many things happened, like armed attacks on the police station by strangers; suddenly there were Kalashnikovs shooting at our building, or car bombs exploding not far away. So I understood Eylem being worried.”

Gradually the situation became safer, and Kilian was able to go out alone and film scenes such as the one where Hala passes through a bustling market and is stopped by a woman in a burka who tells her she wants to join the force. At the police station, Hala listens to women’s allegations of domestic violence, advises victims of their rights under the new regime, and sends out all-female units to make arrests.

Alongside filming Hala, Kilian sought out women who would talk about their lives under Isis for a side project, and discovered “a huge wish to share their experiences, many of which were extremely brutal and shocking.” She also filmed other young women who had joined the military, “I would call them girls,” she says, in some cases because they had lost their families and had nowhere else to go. “One girl had run to the police station because her family wanted to kill her, for some stupid reason. Of course, you can ask if the military is the right place for these young people. On the other hand: is there an alternative?”

“To be honest,” she says, “l’m still a bit full of contradictory thoughts towards what I experienced and other people experience over there in regards to the political and military project of Rojava, and I think my perspective is definitely one of a critical solidarity.”

The film’s ending reflects the mixed emotions and questions with which she left the country. “There’s many very interesting emancipatory ideas going on,” she says, “but then there's like a dictatorship and a raging war continuing, and people are, to some extent, in complete uncertainty about their future.”

Rojava gives women hope and opportunity, and puts them on an equal footing with men, in the military, politics, and at the head of organisations. Society is being changed, but the continuing survival of the autonomous region is far from assured, and some fear that Assad will take back the territory and dismantle all the political structures.

In an illustration of how quickly events can change in Syria, Kilian had to urgently rush back to Minbij not long after returning to Germany, because “all military powers in Syria were around it: US army, Russian army, Iranian army, Turkish army, Assad army, Al Nusra, and the Syrian Democratic Forces. This time it was not clear at all what would happen next,” she says, “and I was afraid that if a new power takes over the city, I would not have access to enter it anymore and would not be able to meet Hala again. So we [her and Namer, whom Kilian had only just met] rushed there.”

What they recorded takes the narrative in an unexpected direction that seems to mirror inconsistencies within Rojava, and the unpredictability of the region itself.

Learn more about ‘The Other Side of the River’ at theothersideoftheriver.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks