More than 30 years later Sweden’s biggest mystery remains unsolved. Who killed Olof Palme?

Before his own untimely death, Stieg Larsson was investigating the murder of the Swedish prime minister outside a cinema. He might even hold the key to solving the mystery of the assassination. Andy Martin on a story that has gripped the nation ever since

What were Stieg Larsson’s final thoughts? For one thing, having finished writing and selling the Girl With the Dragon Tattoo trilogy (together with tv and film rights) he was probably bummed that he wouldn’t get to see them published and enjoy the fruits of his labours. He was almost certainly sorry that he had taken the stairs instead of the lift too. But there was one other subject on his mind that day. An unsolved murder. The biggest mystery of the 20th century in Sweden.

Larsson was not just a novelist but an illustrator and a journalist. On that morning in 2004, at the age of 50, he was going up to the Stockholm office of Expo, a magazine he had co-founded, dedicated to exposing neo-Nazi and racist conspiracies in Sweden and around the world. The offices were on the seventh floor and the lift didn’t seem to be working. So, despite being out of shape, he took the stairs instead. He suffered a heart attack and collapsed before he got to the office.

One of his thoughts was almost certainly, I wish my diet hadn’t been quite so exclusively coffee, cigarettes, and burgers, or why didn’t I take more exercise? But the other thing we now know that was on his mind at the time was: who killed Olof Palme? Olof Palme is Europe’s JFK and his murder in 1986 unleashed a similar torrent of foaming speculation. Palme was the prime minister of Sweden. His social democratic politics and his eloquence in addressing issues of injustice around the world (notably to do with Vietnam and South Africa) had earned him as many enemies as fans and supporters.

Some saw him as a saviour and an icon, others as an obvious stooge of the KGB (before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union) and a threat to democracy. One opponent, who would become a suspect, Alf Enerström, said: “It took a world war to get rid of Hitler. What will it take to get rid of our own Hitler – Olof Palme?”

On the freezing Friday night of 28 February, Palme and his wife Lisbet decided to go to the movies. They went to the Grand Cinema on Sveavägen, in central Stockholm, to see The Mozart Brothers (a Swedish comedy), the 9.15 showing. Palme informed his SÄPO bodyguards that he would have no need of protection that night. It was the last time any Swedish prime minister would utter those words. It was the end of innocence in Sweden.

They came out of the cinema shortly after 11pm, bid farewell to their son, and crossed the street, looking in shop windows. At 11.21pm on the corner with Tunnelgatan a tall man in a dark coat and hat came up behind them, tapped Palme on the shoulder and shot him in the back at point-blank range. A second shot grazed Lisbet Palme. The assassin took off and ran up the steps at the end of Tunnelgatan, leading up to the Brunkeberg Ridge.

A passing student nurse rushed to the aid of the dying man and found herself kneeling in a spreading pool of his blood. That single bullet from a powerful handgun (probably a Smith and Wesson .357 revolver) had severed his spinal column and devastated his internal organs and was enough to kill him. He was aged 59. Lisbet Palme survived. The initial police response was manifestly incompetent: they failed to seal off the downtown area and it was hours before they sent out a nationwide alert.

Beyond that point, facts give way to fiction, fabrication and theory. Which makes Stieg Larsson, the author of some of the most successful novels Sweden has ever produced, who was working in Stockholm late that night, ideally placed to solve the crime. A compelling new book by Jan Stocklassa, The Man Who Played With Fire: Stieg Larsson’s Lost Files and the Hunt for an Assassin unearths and explores the files in the Larsson archives and tries to complete the story that Stieg left tantalisingly unfinished.

Stocklassa’s Larssonesque take on the mystery brings together a cast of Swedish right-wing fanatics, organised and supported by a South African security pro-apartheid black ops team. There is even an Iran-Contra sub-plot. How he manages to arrive at his conclusions in an investigation lasting eight years and recruiting a team of fellow journalists and shady Swedes and a honey-trap Czech woman called Lida, is riveting reading. You can’t make it up. Fact is not only stranger than fiction but even more fantastic. Fiction has to make sense. Reality doesn’t.

Chief investigator Hans Holmer was ill-equipped to handle a high-profile homicide. Almost immediately he tried to pin it on the Kurds. It couldn’t possibly be a fellow Swede?

Stocklassa trained as an architect and worked as a diplomat, but becomes “hooked” on the Palme murder, giving up other projects to become an amateur detective. He says that he “fled from my own private failings and midlife crisis” as he began poring over the Stieg Larsson files, in the middle of a snowstorm, locked away in an obscure storage unit in Stockholm. He patiently reconstructs Larsson’s ideas on the murder and heroically follows the clues wherever they lead. The police had other ideas of course.

The first chief investigator was a man named Hans Holmér (quickly dubbed Sherlock Holmér), who was off skiing with his mistress at the time of the murder. He was a publicity hound ill-equipped to handle the practicalities of a high-profile homicide. Almost immediately he suspected the involvement of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PPK) – Palme had refused asylum to the PPK leader – and tried to pin the murder on the Kurds. It couldn’t possibly be a fellow Swede surely?

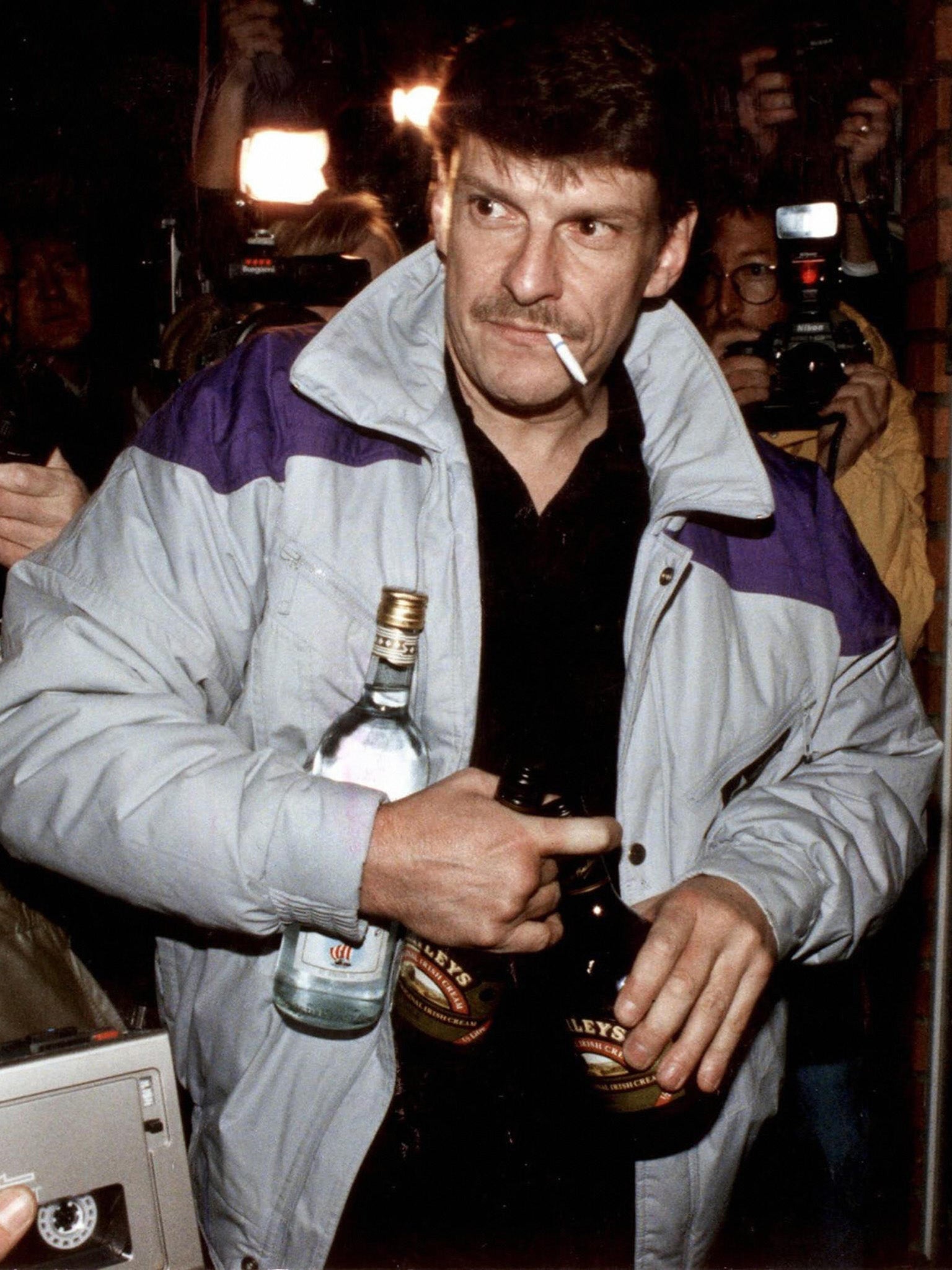

In the second phase, in 1988, the police identified the killer as one Christer Pettersson, a drug addict with mad eyes and a conviction for manslaughter and a string of petty crimes. The case had been solved! Pettersson was put on trial, and found guilty in 1989 – only for the verdict to be tossed out on appeal. As a demythifying documentary made by Axel Gordh Humlesjö, Who Killed the Prime Minister? convincingly demonstrates, the Swedish police, and specifically one cop, Thure Nassén, manipulated the evidence and colluded with “witnesses” (who hadn’t in fact witnessed anything) to produce the desired outcome.

They needed a convenient lone wolf killer (a Lee Harvey Oswald) so they found one. They had zero forensic evidence, nothing but shaky and unreliable identification parades. Palme’s widow Lisbet gave credibility to the case, and convinced many Swedes that Pettersson must be the perpetrator, but her evidence is shown to be skewed by prior police nods and winks. It is not surprising that one popular theory had it that the police themselves were responsible for the murder.

Larsson spotted a connection between home-bred racists and South African secret agents, sponsored by the apartheid regime of PW Botha. Ex-agents and fixers testified about South African complicity to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Their motive had been to decapitate external support for Nelson Mandela’s ANC.

Stocklassa heads off on the South Africa trail to interview the bad guys, finds a “middle man” hiding away in Northern Cyprus, and persuasively builds a case against a Swedish man he calls Jakob Thedelin, who had long fantasised about killing Palme and who becomes the South Africans’ “patsy”, the local guy who can take the fall for the assassination.

Stocklassa travels around Sweden interviewing ageing extremists and ex-movie stars, sometimes going undercover. At times he is on the verge of throwing his hands in the air and giving up. “It felt hopeless. One possibility was to wrap up my research without publishing it, either as articles or a book. I could quite simply give up, which some days felt like a rather appealing option.”

He quite rightly draws the line at an offer from a Mossad operative to squeeze the truth out of his chief suspect. But he perseveres and all the pieces fall superbly into place in Stocklassa’s head – with almost symphonic precision – while he is at a concert, accompanied by Lida (the honey trap).

“What if Stieg could have been here tonight? I’m quite sure he would have enjoyed the concert, but even more, he would have been elated at the possibility that the murder weapon might be found and the assassination resolved thanks to his tireless work, so many years after his death. It would be like a thriller, perhaps one written by Stieg Larsson.” Needless to say, I too was “hooked” by the Stock-Larsson theory.

But there is, as you might expect, an alternative angle. Nearly everyone in Sweden has a theory about who killed Palme. Nearly every year sees another book published by one of the people suffering from Palmesjukdom (“Palme sickness”) pushing a new theory – or reviving an old one – about who-dun-it. It’s virtually a national obsession or pastime. “Digging into the Palme murder was addictive, as many people could attest,” writes Stocklassa. Axel Gordh Humlesjö argues that “we should be sceptical about all the theories. A lot of older men are certain they have found the solution.” His documentary deliberately shies away from coming to a conclusion while successfully debunking the official Pettersson line. Pettersson has now been excluded from the current inquiry, still going on after more than 30 years.

The only thing that makes him interesting is that he was in the vicinity at the right time, but not even the believers have come up with a credible explanation of how, why, and with what he would kill our prime minister

According to a source inside the investigation they are now seriously looking at the figure the Swedes call Skandiamannen or “the Skandia man”. The Skandia man was Stig Engstrōm, who was working at the Skandia insurance offices on Sveavägen on the night of the murder. He disappeared several minutes before the murder took place and had no alibi. And he allegedly had strong right-wing credentials, that might give him a motive for killing Palme. A book nominating him as the killer, The Unlikely Assassin, was published in Sweden in 2018. Apparently the actual detectives were annoyed because the author was claiming credit for solving the crime when he was in fact drawing on elements of their investigation. It is rumoured that “hard evidence” of Skandia man’s involvement in the murder will emerge and police are “optimistic” that the case will be proven.

But Stocklassa is not convinced. The hard evidence he points to is a walkie-talkie he recovered – now in possession of the police – that may have been used by one of the South African conspirators to set up the assassination. Police are currently trying to obtain DNA from the mouthpiece. Stocklassa reckons that the excitement over the Skandia man is the result of three decades with no clear answer and the need for a simple solution. “The only thing that makes him interesting,” he argues, “is that he was in the vicinity at the right time, but not even the believers have come up with a credible explanation of how, why, and with what he would kill our prime minister. Let alone how a weak attention-seeker would be able to keep quiet for decades after the initial interest had worn off.”

Multiple witnesses report seeing men with walkie-talkies that night (an unusual sight at the time – pre-mobile phones). Stocklassa allows that Skandia man could have been involved as part of a larger conspiracy, but not as the killer. Skandia man took his secrets to the grave when he committed suicide in 2000.

Stocklassa himself goes on the hunt for the “smoking gun”. He ends up with an empty bank safe deposit where the gun might once have been hidden. We are left with a cliffhanger. The police talk of coming up with some kind of Exhibit A which would prove the case. But all that is certain is that so far we have no overwhelming evidence. With so many theories and a deficit of data, it is easy to see why someone like Stieg Larsson would be driven to dream up not only a decent hard-working journalist like Mikael Blomkvist, but also a semi-transcendent, tattooed, ass-kicking tech genius of the likes of Lisbeth (named after Mrs Palme?) Salander to solve imaginary crimes and set the world to rights.

And he would probably have been as shocked as anyone to learn that, in a final twist, it was entirely in accord with Swedish law that his “widow”, Eva Gabrielsson, his partner and collaborator of many years standing, saw all the immensely valuable rights for the Dragon Girl books pass into the hands of Stieg’s father and brother, who now control the estate. No crime was committed. But it was. Legally.

Andy Martin’s ‘With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher’ is published by Polity and out now http://politybooks.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments