The winding road to the top for Northern Ireland’s women’s football team

Julie Diamond looks at the long history of women’s football in Northern Ireland, as the team get ready to play their debut game in their first major international tournament – Euro 2022

The trailblazing Northern Ireland women’s football team have made history by qualifying for the Women’s European Championship this summer – their first major international tournament.

Women’s football in Northern Ireland is having a moment. In fact, the women’s game is flourishing everywhere right now: attitudes to women in sport are changing and women’s football is becoming more visible with wider media coverage, increased sponsorship deals, more broadcasting rights and soaring audiences.

My own interest was piqued when I went to see the Northern Ireland women’s team play a World Cup qualifier in Belfast on a cold Tuesday night last September. They won the game, but it wasn’t the scoreboard that got my attention. It was the sheer grit and determination of these footballers on the pitch and the delight on their faces after the match as they waved to the standing and cheering home crowd.

This game took place shortly after they’d secured their place at the Euros, and the pride that engulfed the stadium that night felt special. Like the start of something different for the future of Northern Ireland. Refreshing and inspirational role models offering opportunities for girls and women in sport, and a feeling of hope that cuts across the well-trodden path of sectarian division that has blighted football in this corner of the world in the past.

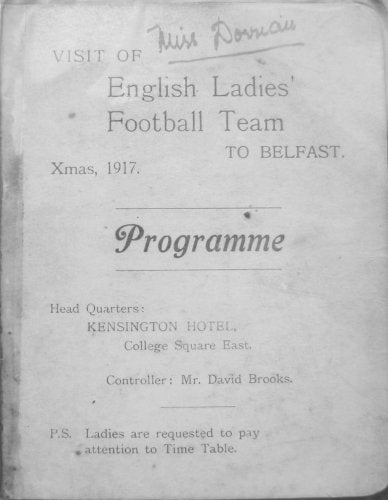

But this isn’t the first time that the women’s game has taken centre stage on these shores. When we look back as far as the First World War, in Northern Ireland and across the UK, the women’s game was booming. While men were sent away to fight, the women were left behind to work in the factories or raise funds for war charities. The women’s game was built organically with the factory workers forming teams and then organising matches as fundraisers. The earliest game of international women’s football in Belfast is recorded as England vs Ireland in Grosvenor Park on Boxing Day, 1917.

The games were a huge success. Attracting large crowds, with live music in the intervals, the matches were hailed as fun, family-friendly events, raising money for a good cause.

But at the height of this early success, in 1921, the FA in England made the contentious decision to ban the women’s game on the grounds that it “is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged.”

Advocates of the ban claimed playing the sport could damage the female form and affect childbearing. But critics believe society was threatened by the popularity of the women’s game over the men’s, and the empowerment the sport gave women at a time when the woman’s role was seen as being at home, in the domestic sphere looking after the family. By banning the sport, women could return to their role as “the Angel in the House”, and the men back from the trenches could retain their space on the pitch without the threat of the thriving women’s game.

Lasting 50 years, the ban unsurprisingly fostered attitudes toward football as a man’s game. It’s difficult to say how the ban in England directly impacted the women’s game in Northern Ireland. The evolution of women’s football in these parts has gone largely untold – until Belfast actress and writer Tara Lynne O’Neill, best known for playing “Ma” in TV hit Derry Girls, decided to write a play documenting the early pioneers of women’s football.

Rough Girls tells the story of the first all-female football team in Belfast towards the end of the First World War. Bringing to life forgotten heroines like Belfast’s Molly Seaton – or “Big Molly” – who was well-known back then for her strength and power on and off the pitch, and who fought hard for the survival of the women’s game.

“I’m obsessed with stories about where I’m from, which is Belfast,” says O’Neill, “and stories that haven’t been told. And they happen to be mostly stories about women because it was the men who wrote the history books, so to speak, so women have been left out.”

Researching the topic extensively, she pored over official records from the Irish Football Association (IFA), yet could find no trace of the women’s game in its earliest days. All her evidence came from press cuttings.

“The newspaper library in Belfast has papers right back to the 1800s; the Northern Whig, Ireland’s Saturday Night, everywhere pictures of the girls playing football. They were becoming their own celebrities and becoming well-known within the community.”

“Yet they never made any dent in the official records, and I think that’s what made me want to write it. I just wanted to say: ‘This happened, let’s mark it.’”

Although O’Neill had been working on the story for years, it was lockdown that spurred her on to bring the play to the stage. And in a coincidental turn of events, the timing of the play chimed perfectly with the present-day women earning a place at Euro 2022.

In the same way the early pioneers like Seaton pushed boundaries all those years ago, the close-knit team of women in the current international team are blazing a trail for the women’s game here in Northern Ireland.

Director of Women’s Football at the IFA, Angela Platt, says the women’s current success is the culmination of decades of hard work and determination below the surface, which is now coming to fruition.

“There has been a lot of people that have carried the baton for women’s football before my time,” says Platt.

“Our journey within the Irish FA really started in the early 70s when women’s football began again [after the ban] and when the Northern Ireland Women’s Football Association was formed.”

Set up in 1972, they sought to rebuild the game after the 50-year hiatus. Not an easy task at the time as the association faced criticism, ridicule and financial obstacles due to gender inequalities and negative, stereotypical attitudes towards women in football.

“They really took the first steps to develop that organisation and start to provide those opportunities for girls and women’s football again. There has been a long journey with a number of people who have worked so hard across a number of years to get us to the stage we’re at.”

The trajectory of the women’s game in Northern Ireland was interrupted in 2000 when the Irish FA decided to pause senior international women’s football to focus on the girls’ youth programmes – in a bid to give the game longevity for future generations.

Although the side was reformed again in 2004, the women’s international game was standing on shaky ground, and the squad were forced to fundraise to pay their own way to play at the Algarve Cup in that same year.

Former Northern Ireland player Gail Redmond was on the team that travelled to Portugal. She remembers: “It was very amateurish in the sense of our preparation, we paid to go to it and they didn’t give us any gear in between sessions.

“It was a starting place, and there’s probably frustrations that we didn’t move as fast as we could. It took us a long time to try and change mindsets to make it better with better facilities.

“We had a summer league because we couldn’t get a pitch in a winter league. No one would give us a pitch, and those conversations never took place because as females of that generation, we were just thankful to play.”

During this tense time, a sea of red, white and blue fans would fill the stadium with sectarian chants and sometimes bigoted abuse towards their own players

So, with limited finances and minor recognition, the women’s game continued to slowly grow and develop below the radar.

Meanwhile, the men’s game grabbed the spotlight, though not always for the right reasons. There were many magical footballing moments, thanks to the likes of George Best, Pat Jennings and David Healy. But like many aspects of life here, football has been largely entwined with politics. Against the turbulence of the Troubles, the men’s game was often plagued by religious division and sectarian hatred.

Growing up a Catholic in Northern Ireland, I didn’t support the national men’s team but instead rooted for the Republic of Ireland on the international stage.

Typically in Northern Ireland, Protestants supported Northern Ireland, but many Catholics shunned the national side in favour of the Republic of Ireland. Being Catholic and nationalist, we wanted to see ourselves as “Irish” and part of Ireland, whereas typically Protestants are proud of being “Northern Irish” and therefore proud to support the Northern Ireland football team. Although of course there are exceptions and this isn’t going to be the case for everyone, but it was the case for me and those around me in my formative years.

Besides, the national stadium of Windsor Park – situated in a Protestant, loyalist heartland – had a reputation during the Troubles as a hostile, unwelcoming environment for Catholics, and was an embarrassment for many Protestants who didn’t want to get caught up in any religious hatred.

During this tense time, a sea of red, white and blue fans would fill the stadium with sectarian chants and sometimes bigoted abuse towards their own players. This febrile atmosphere on the terraces reflected the divided society of the time. The sectarian hatred reached its peak in 2002, when Catholic player and team captain, Neil Lennon, received a death threat.

All this turmoil signalled a need for change and prompted the IFA to set up the “Football for All” campaign in the early 2000s, in an attempt to wipe out sectarianism and create an all-inclusive and safer environment.

For the campaign, supporters were encouraged to wear green and white (as opposed to red, white and blue) and large groups would arrange to book tickets together in the stadium. When any sectarian songs would begin, they would out-sing them with new, neutral songs like “Green and White Army” or “We’re not Brazil we’re Northern Ireland”.

The idea was simple but effective, and helped change the atmosphere at Windsor Park. It’s an impressive achievement that shows what can be done and that change can happen. Although in a country hugely dominated by the past and where sectarian divisions still linger, it’s unlikely the initiative has changed everyone’s opinion of the stadium – change takes time in Northern Ireland.

When I went to watch the women’s match at Windsor Park that September evening last year, it was my first visit to the national stadium, and although climbing the stairs to the stands I carried inside me the weight of the past, as the match progressed it surprised me that a ground that was once unsafe and contentious felt effortlessly inclusive and welcoming – full of families cheering on the footballers with no shade of politics or tension in the night air.

There are families, young boys, young girls from all aspects of our community that want to come and watch our successful women’s team, those role models

The women’s game hasn’t been blighted by the weight of sectarianism, which offers hope for the future – not just for the women’s game but the men’s game too. And as excitement builds for the Euros, this team has the power to help unite a country often torn by division.

It’s not the first time that sport has bridged the divide though, football hasn’t always been a source of division in Northern Ireland.

Footballing legend Gerry Armstrong was part of the magical Northern Ireland side of the eighties that famously brought the country together in jubilation at their success in the 1982 World Cup – even at the height of the Troubles. Striker Armstrong became a national hero for scoring the winning goal against the hosts of the tournament, Spain.

“We had hundreds and hundreds of messages from all different denominations, from the Reverend Ian Paisley, from the Bishop of Down and Connor, people from the south of Ireland congratulating us. Everybody,” remembers Armstrong.

“And then we had a situation where Norman Whiteside’s mother came from the [Protestant] Shankill Road across to meet my mother and have tea with her on the [Catholic] Falls Road. Those sort of things were unprecedented.nSo we actually united the whole of the country, and it was a brilliant time.”

Although Armstrong is from a Catholic background, raised in the Falls Road, he took great pride in representing Northern Ireland and didn’t experience any sectarianism or bigotry from the fans, despite the surrounding political turbulence.

“That was one of the things that really struck a chord with us, we did something that the politicians couldn’t do, they couldn’t bring the country together, but we could as a football team.”

The unifying force of the golden 1982 side shows the power of the sport to bring people together. Especially success in sport. And while in years gone by these moments were fleeting, and the depth of division would return, there may be something about this current group of women that has a more lasting effect.

“We’re in a different place with our women’s team and it’s really exciting to see that,” says Platt at the IFA. “I think we’re really seeing an evolution of the fan that follows Northern Ireland.”

“There are families, young boys, young girls from all aspects of our community that want to come and watch our successful women’s team, those role models. We have sold out the national stadium of Windsor Park on Tuesday night [the World Cup qualifier with the Lionesses] with 16,000 people coming to watch that.”

Platt is passionate to ensure that this moment of hope for change both in the women’s game and against sectarianism is not just a “one-off”

“I would say it’s our responsibility collectively to make sure that we don’t lose the opportunity,” says Platt. “Legacy for us is so important to build on; not just having one moment of time that is in the history books.”

Rough Girls playwright O’Neill points out that whilst looking to the future, it’s also important to look back at the forgotten heroines in years gone by whose bold and brave steps helped lay the foundations for this type of change. And likewise, this generation of women are paving the way for future generations.

“It’s great to remember and reflect on the people that weren’t allowed to do that and remember this is where we are, people have fought for this.”

And one of those game-changers, Redmond who captained Northern Ireland in the 2000s says: “I hope that with the next generation, that we’ve done such a good job that they say: ‘What! You had to pay to play? What! You couldn’t get a kit? You used the men’s?”

“Those days are gone – the days when you had to give your tracksuit back in the toilet of an airport are gone now.”

A major breakthrough in women’s football came this year when the Northern Ireland team achieved professional status ahead of the Euros. A long way from having to pay to compete in a tournament.

“I chat regularly to the younger players,” says Redmond, “and say to them: ‘You have to make sure the jersey’s left in a better place for the next generation.’

“Previous generations fought hard for change. We hope, then, that the next generation doesn’t forget that – the barriers that they had to fight through – and that we continue to celebrate that success.”

Playwright O’Neill sums it up beautifully: “Every generation had somebody who tried to push the goalposts. And they might have only nudged them over a wee bit, but this team are just breaking the nets.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments