‘How can we avoid dying today?’ A North Pole expedition to chronicle black carbon

The first ever recipient of the Shackleton Medal for the Protection of the Polar Regions sat down with Rachel Halliburton to explain what it’s like recording ‘black carbon’ in the Arctic

As she watched the storm approaching across the exposed Arctic plateau, Dr Heïdi Sevestre knew she was facing a life-or-death situation. From the start of their expedition across Svalbard, it had become clear that she and her team of female scientists were facing freak weather conditions. Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago that sits around half-way between Norway and the North Pole, normally enjoys settled weather in April; a high-pressure zone generates cold sunny days, almost crystalline in their stillness. Yet in the spring of 2021, when the pandemic had temporarily eclipsed the threat of global warming for most of the world, her team found themselves on the frontline of a lethal battle with the elements.

“On day one of the expedition I noticed that temperatures were high,” she says. “Normally it’s between -15 and -10C, but when we started it was 5C. The winds were insane – up to 140km/h. Because of the warm temperatures there were avalanches and the crevasses on the glaciers were opening up. There was also a lot of snow. Every step we took, every decision we made was underpinned by the question: how can we avoid dying today?”

There’s no swagger or melodrama to this declaration. Sevestre may have dedicated herself to living and working in extreme environments, but her dominant mode is upbeat calmness. On the day when her team was ambushed by the storm while they were on the plateau, she tells me, there was nowhere to shelter, just ice, snow and rock. As the fierce winds whipped up, they realised there was only one option, they had to bury themselves in the snow as fast as they could to survive.

“At the time it felt normal to do this,” she says with a laugh of disbelief. “The strength of the team really shone through here. We were all very different people, but you need that. We learned not to be scared to talk about being anxious, because if you’re feeling negative it’s likely other members are feeling the same way. But we also learned to stay calm and collected when facing the most stressful conditions possible.”

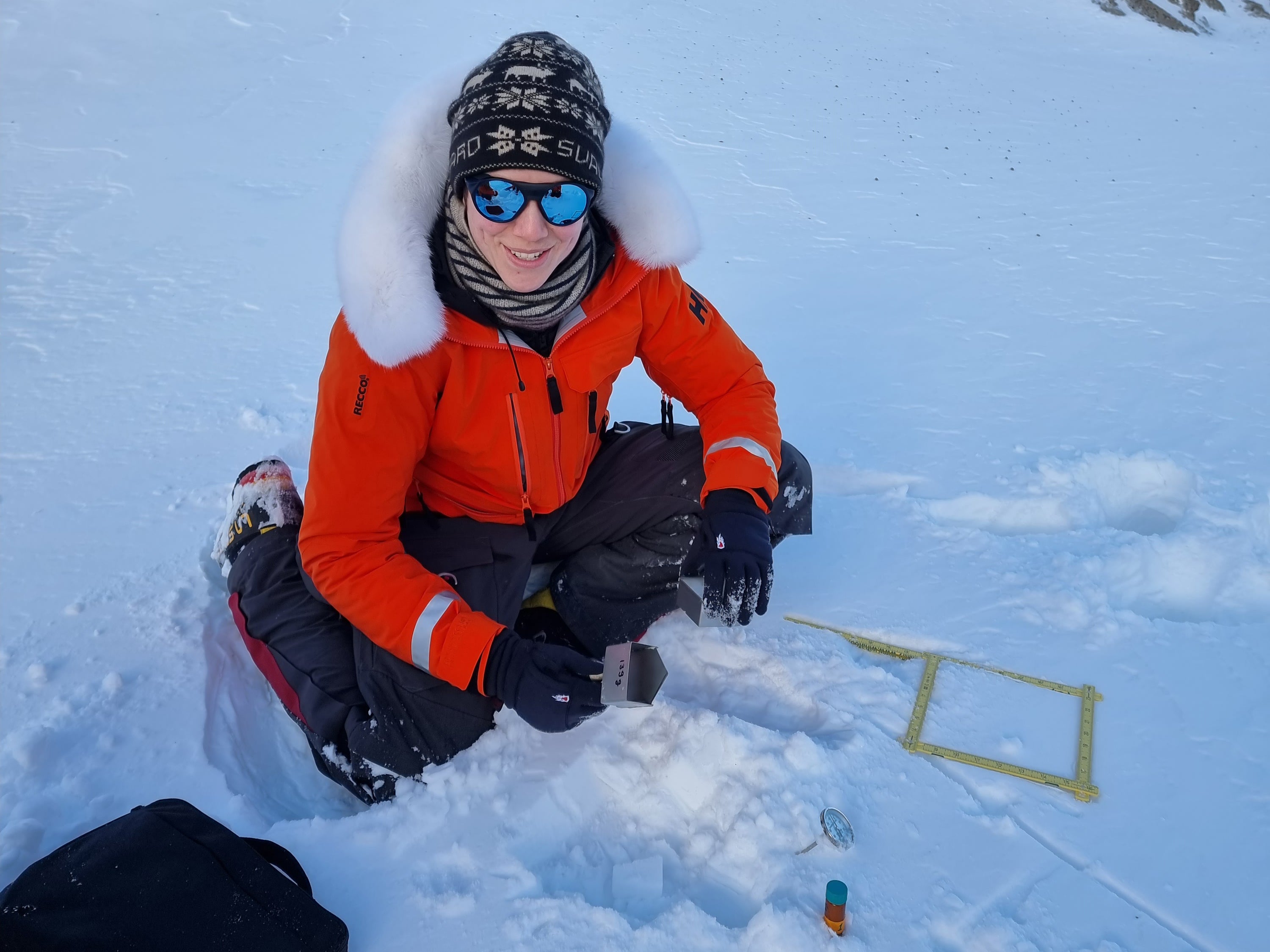

Officially they called themselves the Climate Sentinels; the aim of their expedition was to chronicle the phenomenon of “black carbon” or soot, the airborne pollutant that – it’s been estimated – accounts for 15-30 per cent of recent warming activity in the Arctic. As any glaciologist will tell you, the ice at the poles protects the planet from warming in part because of the “albedo effect”, in which 80 per cent of the sunlight that strikes the sub-zero whiteness is bounced back out into space. Recently environmentalists have observed that exhaust fumes from increased ship traffic in the Arctic – itself a disturbing by-product of receding sea ice – have alone deposited 85 per cent more black carbon in the region. The impact is exponential; the moment the glacial surface turns black it loses its ability to deflect heat and starts absorbing it, just one of the reasons why the Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world.

For Sevestre, as for her team, there was no doubt that they should keep going. “What we did was in the name of science. We didn’t just want to survive, we wanted to continue our research programme.” One of the challenges she had set herself was to make the entire project carbon neutral. Over the course of five weeks the women travelled 450km on skis and only slept in tents. “Being in this environment makes you very humble, you have to understand that this place is stronger than you,” she says. “When you’re in a violent blizzard for days, with your tent juddering like a washing machine, it can be difficult to stay positive. But then you look around you, at the snow, at the light, and this cold, rough, harsh environment is mesmerising.”

Now it’s against regulations for people to be buried there; because corpses freeze rather than rot, they preserve viruses that killed them

It’s not difficult to see from her simultaneous calm and passion why the 34-year-old Sevestre is a fast-rising star in the polar world. In the seven years since she got her PhD in glaciology from the University of Oslo, she has made it her mission to connect everyone from schoolchildren to heads of state with the urgency of what she and her fellow scientists are witnessing. “I remember the reactions when a group of us addressed MPs in the UK; each of us had five minutes to talk about our subject whether it was permafrost, ice sheets or glaciers,” she recalls. “Their jaws were dropping. We thought ‘at least they’re getting it now’. But then they didn’t take the action we expected, and we realised the huge gap between people understanding the issue and taking the decisions needed to change things.”

We meet in Geneva, on a day when the unusually warm March weather is making its own deceptively benevolent hat-tip to global warming. Sevestre has travelled from Annecy, the French town where her family is based, because she is receiving the Shackleton Medal for the Protection of the Polar Regions, which gives £10,000 to further the research of inspirational individuals working at the poles. One hundred years after Ernest Shackleton died, the medal has been designed to celebrate those who display the same courage, determination against the odds and selflessness that make his own story of polar exploration resonate with individuals around the world today. Earlier in the month, an independent panel of polar experts – chaired by the author and research scientist Lewis Dartnell at London’s Royal Geographical Society – has decided that Sevestre is its first winner.

When she first walks into the meeting room at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel, on the banks of the River Rhone – which shimmers like metal in the intense sunlight – she cuts a demure figure with her cropped hair and olive-green coat. As she starts talking, it takes a while to compute that the scenes she is describing would not be out of place in a horror movie. Though Sevestre is French, her work is based in Svalbard’s Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town, where she says the receding permafrost is forcing decades-old coffins to the surface. Now it’s against regulations for people to be buried there; because corpses freeze rather than rot, they preserve viruses that killed them. Some have been discovered to be contaminated with the Spanish flu that wiped out 50 million people across the world after the First World War.

Yet Sevestre loves Longyearbyen, not least because here she can indulge the obsession with ice that dates from her growing up in the French Alps. “From day one, I immediately fell in love with ice,” she says. “It’s not just the beauty of the environment, it’s everything round it. When you go on a glacier you have to dress up in a certain way; the thick clothes, the big boots, the helmet, the ice-axe. To me it felt like being an astronaut and being on the moon every time I worked on these glaciers.”

It’s just one indication of how extensive the study of ice is that her analogy between being an astronaut and being a glaciologist isn’t far-fetched. Many polar scientists – including Sevestre – work with satellite operators at Nasa and the European Space Agency, comparing what they have observed in the field with the patterns being observed from space. Others study sub-glacial lakes – which, because they are cut off from sunlight and the Earth’s atmosphere, provide important clues about extra-terrestrial life. There are research stations in the hostile conditions of the Antarctic that conduct experiments about the possibility of growing vegetables on Mars. One of these research stations, Concordia, boasts on its website that it is more remote from civilisation than the International Space Station.

Passion is essential. Determination is also important – if you don’t have a well-defined goal it’s very hard to find a route

My own conversations with the polar experts who have decided that Sevestre is this year’s medal’s winner have shown that these are just a few examples of how wide-ranging the apparently esoteric study of ice can be. Put the microscope on this planet alone, and there are ice cores that tell us about what was in the atmosphere hundreds, even thousands of years ago through trapped air bubbles. There’s the fast-growing area of expertise that combines the ancient wisdom of Inuit and other peoples indigenous to the Arctic with the latest technologies for studying ice and climate change. Meteorologists can demonstrate how the loss of ice at both poles is causing everything from cold snaps in the Middle East to crop damage worldwide. Beyond this, whether it’s the link between melting glaciers and rising sea levels or the emergence of new polar shipping routes, the story of ice clearly impacts on everyone.

This January, Sevestre was appointed to work on the prestigious Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (Amap) for the Arctic Council, the international organisation that researches and coordinates responses to pollution at the North Pole. She tells me that she had decided early on that the story she wanted to tell about ice couldn’t be achieved through academia alone. “Glaciology is a young science filled with passionate people – and the responsibilities we have are absolutely major,” she says. “When I’m with my colleagues, we agree that we have to make our science more accessible, we have to continuously fight to connect people with the magnitude of what is taking place. Most importantly we have to empower people to act positively to achieve change.”

Certainly, she’s determined to get her message out through any medium she can. As well as directly addressing politicians and schoolchildren, she has presented science documentaries for the French TV channel France 5 and Argentina’s Ushuaia TV. There’s also social media. “I love social media,” she says, “because again, we have to use all the tools available. I think scientists should be on TikTok, scientists should be on Snapchat, they should be on Instagram, on LinkedIn, on Twitter, on Facebook, we should try to dominate the space.”

One of the best aspects of being on social media, she feels, is being able to answer the wide range of questions that are thrown at her. “You can talk about numbers,” she says, “but what people really want to know about are your experiences from the field; what you can see, what you can hear, what you feel when you’re standing on an ice shelf.” Sometimes she’s asked about how she deals with the threat of polar bears, other times “people want to know how you sleep in these environments, how you brush your teeth or how you go to the bathroom. I like answering these questions because it’s about building trust in science, showing we’re just human beings trying to make a difference.”

As well as highlighting her achievements, her Shackleton medal brings with it the reminder that 100 years ago the Arctic and Antarctic were seen as a no-go zone for women. That only started to change in the 1950s and while the number of female polar scientists has increased significantly since the 1990s, it still takes exceptional individuals to smash through what’s known as the “ice ceiling”. Still, Sevestre feels a strong connection with Shackleton’s experiences, and is fascinated about what it might be like to have a conversation with him. ‘We often talk about him in the field. His leadership, his skills in bringing different kinds of people together, his determination against unbelievable odds.’

What qualities does she think are needed in those who want to work at the poles today? “Passion is essential. Determination is also important – if you don’t have a well-defined goal, it’s very hard to find a route to achieve what you need. From my experience the third quality is empathy. When you’re working with a team in this challenging environment everyone will struggle at some point – and it’s important to respect each other’s needs and feelings. I remember one of my supervisors used to say on day one of every expedition, ‘I'm the biggest chicken out here. OK, I'm always cold, I always want to go to the bathroom. So we're all on the same level here, let's just admit it, OK?’”

One of the issues Sevestre talks to people about is the importance of voting for politicians with credible climate policies. “We have to help people understand that we shouldn't wait for a technology that doesn't exist to help us to solve the climate crisis. It's by making collective actions and collective decisions that we can fight this big challenge. If, through my work, I can plant a little seed here and show people that we can still avoid the worst consequences of climate change, it will help. That awareness needs to dictate the next five years. We’re in a race against time.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments