The might of algorithms – and what it says about choice

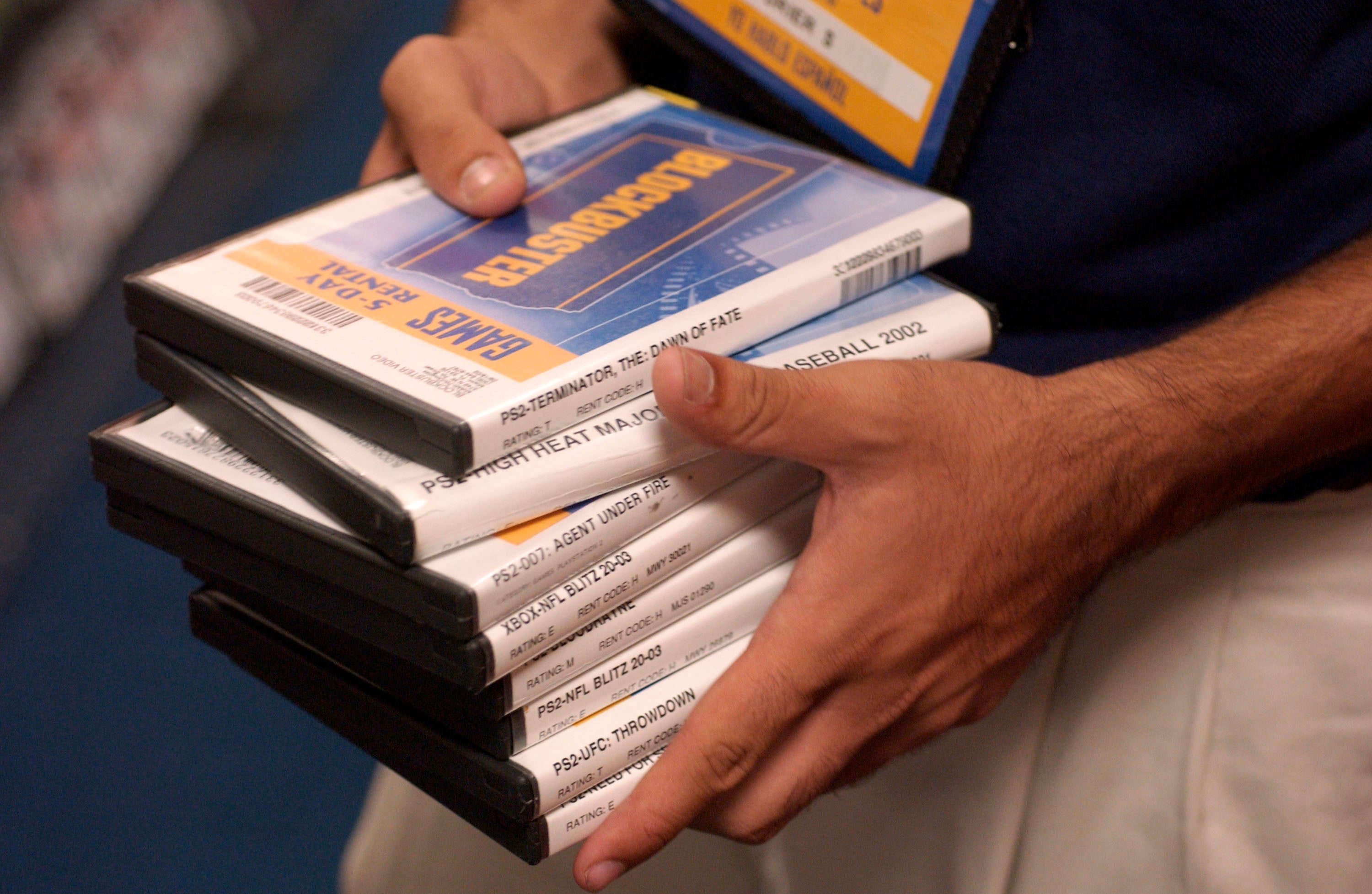

Once upon a time we went to a shop and rented a VHS or a DVD, we spoke to humans and sought recommendations. Now, what we watch is often guided by algorithms but is that a good thing, asks Ryan Coogan

I was watching Netflix recently and a show called Blockbuster popped up on my list of recommendations. It’s a 10-episode Netflix original sitcom that shares a lot of DNA with shows like Superstore and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, about a fictionalised version of the last Blockbuster video store in the US.

The show’s fine, though there’s something about it I feel is borderline obscene. This is a comedy show about how the rise of streaming platforms killed off the video rental industry. It’s like watching a serial killer write taunting letters to the police, daring them to catch him.

It’s strange to see Netflix make a show that so blatantly exposes what I see as the flaws in the streaming model. One of the running themes of Blockbuster is that sites like Netflix didn’t just kill off the movie rental industry, but also fundamentally transformed the relationship that people have with the media that they consume. Travelling to a specific location, asking for recommendations from knowledgeable flesh-and-blood employees, making a choice about that evening’s entertainment, and being tied to that choice for the entire evening are all things that have been relegated to a nostalgic past along with Pogs and cassette tapes.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. I appreciate the value of not having to put on trousers and drive into town if all I want to do is sit at home and watch When Harry Met Sally. I’m also aware that nostalgia plays a big part in my romanticising my own inconvenience. But there’s something to be said for a version of culture that doesn’t treat entertainment as “content”, and choices about how we consume that entertainment aren’t influenced – if not explicitly dictated by – algorithms that guide us along the most financially lucrative pathways at the expense of genuine, human engagement.

While there’s no indication that we’re in any real rush to return to the days of VHS and chill, there are signs that the streaming model may be on its way to reaching something of a ceiling. Earlier this year, Netflix reported a loss of nearly one million monthly subscribers, which the company itself admitted was a “better than expected” result. Services including Netflix, NowTV and Disney Plus have begun offering cheaper streaming plans that include advertisements, to help tempt users back to the sofa. Music streaming giant Spotify has tempered its shareholders’ expectations for growth in the past year.

None of this is to suggest that the streaming industry is going to have its bubble burst any time soon; factors such as lower household entertainment budgets due to the cost of living crisis, and several platforms’ decision to suspend their services in Russia due to the country’s invasion of Ukraine, have both been cited as potential reasons for any perceived slowdown in business. But the fact that there’s been any slowdown at all for companies whose services amount to “a near-unlimited selection of films and television shows for the cost of a single DVD every month” is worthy of comment.

It isn’t just streaming services either, as social media begins to feel the sting of reduced user interest. Last month, Meta’s share value dropped by nearly 25 per cent to below the $100 mark, partly due to the weak performance of one-time giants of social media Facebook and Instagram. TikTok has seen a decline in the average time that users spend engaging with the app; a trend that is projected to continue into 2023. Twitter’s new owner seems to be driving people away from it.

Part of the reason for this can just be pegged to the limits of capitalism as a system. If your business model is to endlessly grow at an increasingly accelerated rate, you’re going to run into a brick wall at one time or another. But there’s also something to be said for the simple fact that offering people endless hours of entertainment, that they can watch at any time they please, is going to burn them out eventually.

It’s counterintuitive, in a way. How can offering people near-unlimited choice in what they consume ever be considered a bad thing? If I subscribe to Netflix, I can filter by genre until I find something that’s right for me. If I have a Twitter account, I can choose who to follow. I’m not necessarily being exposed to anything that I don’t want to see.

While we are given a theoretically unlimited choice when it comes to our viewing habits, that choice is carefully guided to encourage us to consume more

But that isn’t how it works in practice. When we talk about consuming entertainment, we don’t use the language of fun and games. We use the language of business. We’re well aware of our status as gullible marks for corporations, being fed an endless trough of content that we swear, we can quit any time. App monitoring firm App Annie revealed in a study that the average person spends around 4.8 hours on mobile phone apps per day. That isn’t a hobby; it’s a habit.

A big part of the reason for this is the algorithmic model that most of our online entertainment platforms are founded on. While we are given a theoretically unlimited choice when it comes to our viewing habits, that choice is carefully guided to encourage us to consume more, or to consume content that may not be to our tastes normally.

Netflix, for example, will tailor the thumbnails of its movies and TV shows based on our viewing habits to make them more appealing to us. Do you watch a lot of romantic comedies on your Netflix account, and would never dream of watching a scary show like Stranger Things? Netflix might try to sway you by showing you a picture of one of the show’s female leads, instead of the monstrous Demogorgon. Did you watch The Avengers recently? You may end up seeing a thumbnail for Pulp Fiction that features Samuel L Jackson instead of Uma Thurman. I asked Netflix to comment on the way they use algorithms to guide their customers’ viewing habits, but they didn’t respond.

I asked Paul Armstrong, author of the book Disruptive Technologies, to reflect on some of these points and share his thoughts on just how sophisticated these algorithms can be, ask well as how effectively they are able to gauge users’ interest in a particular genre:

“Algorithms are being reviewed... at the highest levels of government around the world for a variety of reasons, and none of those reasons are good,” he says. “The fact remains that there is minimal visibility at all levels about who creates these algorithms, how they are altered over time, and who oversees the creation and alteration.

“Netflix and pals need not just to find something for users to watch, but the best thing to watch at any given moment. In other words, the algorithms need to essentially read minds to find the optimal programme for that moment. I foresee a day when we are asked by Netflix what our goals are for the year or quarter, in order to help them better serve our needs.

“All platforms can make millions – if not hundreds of millions – of people watch something if it’s the first thing that the viewer sees when they flick the service on. The front page effect takes over; users assume that because something is on the front page it must be interesting or popular and click: the viewer is in. Neither of those things may be true; the streaming service just uses real estate in that way. The algorithm might just help show you a genre or an actor you have watched a lot of, but beyond that, popularity can be based on factors that are as dumb as a bag of rocks.”

David Ingham, Head of Media, Entertainment and Sport at Cognizant, a technology services and consulting firm, has a more positive view of algorithms, and their potential to improve not only streaming services’ bottom line, but the users experience too.

“Sometimes no matter how much changes, certain things stay the same,” he says. “A cliche with cable was you could be channel surfing across 100 channels and still have nothing to watch. We are in that age of streaming, where now we are scrolling instead of surfing, without landing on anything to watch.”

“Keeping things simple and easy is key to keeping people on a streaming platform. If it becomes difficult for a user to find the programme they want to watch, they can begin to disengage with what is available to them. This is turn leads to them evaluating whether they want to remain on that platform or move to one that has content they do want to watch.”

However, algorithms can often have a much darker facet to them. YouTube, for example has had far-right and hateful content appear for viewers who otherwise would have no interest in the subject (not that it would be much better if they only showed them to people who were explicitly seeking them out).

In 2019, 28-year-old Brenton Harrison Tarrant killed 51 people and injured 40 others in a mass shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand which the country’s government later partly attributed to Tarrant’s radicalisation via the site. Anti-radicalisation activist Caleb Cain said in an interview with Sky News that his own descent down the far-right rabbit hole initially began when he was looking for self-help videos, before being offered thousands of videos about “male supremacy, racial supremacy, and cultural supremacy... anti-feminism, the dangers of Muslim immigration or the dangers of liberalism”.

YouTube pointed me toward a study carried out by researchers at Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania which found no evidence that “echo chambers” are caused by YouTube recommendations. This, they say, was backed up by other researchers who found that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm actively discourages viewers from visiting radicalising or extremist content by favouring mainstream media over independent YouTube channels.

A YouTube spokesperson said: “Over the years, we’ve worked hard to implement products and policies that help us protect children and families and connect them to high-quality content on YouTube and YouTube Kids. We have clear policies that prohibit content that endangers minors on YouTube and remove violative content as quickly as possible”.

Algorithms dictate 21st-century viewing habits, for better or worse. Is it any wonder that people may finally be growing tired of an entertainment culture dictated by an algorithm that’s only interested in their ad views and outrage?

There’s also the more banal issue of simple content burnout. When I was a kid, you’d buy a movie or an album, and you’d be stuck with it until you had money to buy another one. There’s a reason that a lot of millennials’ favourite films are movies that were made a decade before we were born, like Ghostbusters or Back to the Future; that’s what we had, and we were going to like it.

It’s hard to know whether the trade-off is worth it, though. When we’re able to watch what we want, when we want, it numbs us to things we might otherwise have cherished

Prior to the modern internet, your music tastes were limited, so you learned to appreciate what you had. I’m aware that’s a very boomer sentence, but it’s true. You’d wear out a VHS copy of the worst straight-to-video film you’d ever seen in your life, and you’d love it, because that was what was available. You’d stumble across The Long Kiss Goodnight on Channel 4, and you’d appreciate every second of it because it was something new, and you weren’t sure when you’d get a chance to see it again.

I think this is part of the reason that movie studios have leaned so hard on sequels and remakes of older properties in the past few years, too. People like to handwave it away as companies simply capitalising on nostalgia, or the fiction that there just hasn’t been a good, original property released since the early-2000s, but I think it’s more complex than that. Because that older generation engaged so thoroughly with the media we had access to as kids, and burned it into our memories so vividly, we’re still excited for new chapters to those stories. Once upon a time, you’d be lucky to get a sequel to your favourite film, or an adaptation of your favourite comic, but now you can’t move without tripping over an expanded universe or a TV miniseries based on something that was released last year.

“Algorithms are just feedback loops,” Cultural historian and jazz musician Ted Gioia tells me. “They can never guide you to anything that’s really fresh and new – and for the simple reason that they look at the past, not the future. The song they recommend tomorrow will sound much like the song they recommended last week or last month or last year.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the pace of innovation has slowed almost to a halt in popular culture. The movies are mostly brand extensions and remakes. The songs are even worse—market research shows that people actually prefer old music nowadays. The entire culture is caught up in the past. But that’s exactly what algorithms deliver. The more we rely on them, the more we stagnate—both as individuals and as a society.”

There’s another side to the coin, obviously: there’s a democratising effect to having access to the entire history of human cultural production at the click of a button for less money than it would cost to go to the cinema once a month. Even with the more decentralised streaming environment in which we now live, where instead of one streaming service you’re expected to subscribe to three or four to be caught up on everything, you still have access to more forms of entertainment for less money than at any other time in human history.

It’s crazy going back to watch old seasons of my favourite TV shows that I originally watched in syndication, and realising that there were seasons of content that I’d missed the first time around because I wasn’t home on the right evenings. There are films that I’ve always wanted to see, that will occasionally pop up on my Amazon Prime recommended list like an early birthday present. It also has the potential to broaden our horizons; I’ve managed to convince friends and family to watch things they never would have considered before because, well, what do they have to lose? You can become a fan of something you may never have otherwise experienced if you’d had to drop £60 on a DVD boxset.

It’s hard to know whether the trade-off is worth it, though. When we’re able to watch what we want, when we want, it numbs us to things we might otherwise have cherished. Being guided through a media landscape by the algorithmic equivalent of HAL 9000 makes media consumption a passive activity; something you just do because it happens to be an option. Sure, you’ll see a lot of new things, but algorithms are designed specifically to make those new things as bland and familiar as possible – even if you may otherwise have avoided them.

We’re probably never going to return to an age of limited choices, or careful curation, and maybe that isn’t a bad thing. But if we’ve reached the event horizon of what unlimited consumption can bring us, I’m interested to see what we replace it with.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments