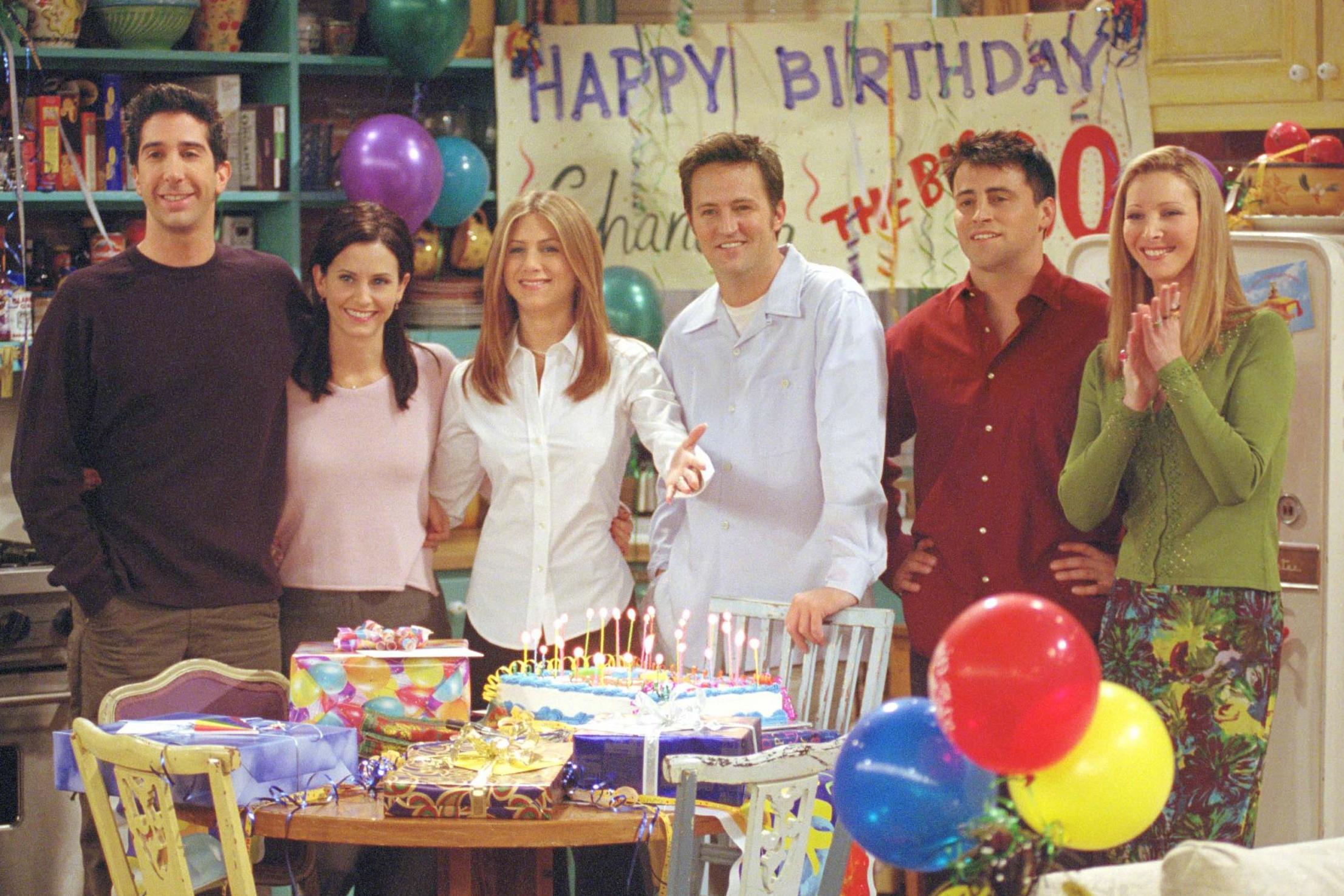

Streaming giants are banking on our love of shows like Friends to keep us watching... and paying

Overwhelmed by the multitude of new shows and films released on streaming platforms fighting for our attention, viewers like Clémence Michallon can be left craving the familiar. And platforms such as Netflix, HBO and Disney will pay millions to be your ‘comfort food’ television

When Reed Hastings, the co-founder, chairman and CEO of Netflix, sat in front of an audience at King’s College in Cambridge in September, the myriad of challengers to the company’s streaming market crown was likely to be a hot topic. After all, the event took place weeks after it was officially confirmed that Friends, the same sitcom that reportedly prompted Netflix to spend $100m (£81.4m) to keep it in its catalogue throughout 2019, would leave the streaming platform in 2020 for WarnerMedia’s HBO Max, in a deal believed to have reached $425m. Hastings’s keynote address also took place just three days after NBC’s unveiling of its own streaming platform, the upcoming Peacock, which will yank The Office and Parks and Recreation, two legacy shows, from Netflix in the US.

Yet, based on what Hastings told the crowd, he doesn’t seem too worried. “Sometimes you do your best work when you’re really challenged,” he said. “We’re really about trying to find great stories.” However, this was coming from the same man who admitted that Netflix got outbid for Fleabag, the Phoebe Waller-Bridge show that went to Amazon Prime and won four Emmys two days after Hastings’s address.

A number of insightful pieces have been written about the fight to find the right price point – with some services looking to undercut Netflix – as well as companies such as Disney looking to steal a share of the market. Hastings himself is sure that producers like Waller-Bridge – who reportedly banked $20m from Amazon – should benefit from the impending bidding wars that are sure to erupt when studios can take their shows to a multitude of platforms.

But for viewers, this bewildering landscape can leave them craving the familiar, having already been overwhelmed by the stream of new content that talented showrunners insist on thrusting upon us every day. I, for example, only subscribe to the Holy Trinity of streaming platforms (Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime) but I could watch TV all day, every day for a week and still barely make a dent in my unending to-watch list. I need to finish Unbelievable, Netflix’s brilliant show about a real-life rape case. I’ve barely started Succession, the best series on TV right now if my Twitter feed is to be believed. I need to dive back into Killing Eve as the third season has now entered production. I desperately want to start Ryan Murphy’s The Politician. I never even started Chernobyl, I’ve barely scraped the surface of The Marvelous Mrs Maisel, and I failed to follow through on watching Sharp Objects.

So what do I do, when I’m drowning in a sea of new shows and am left desperate to switch my brain off for about an hour? I turn to what one might call “comfort food” television, ie a show I have already watched and metabolised, meaning it will be stripped of the emotional labour that comes with having to get attached to a cast of characters for the first time, leaving only the entertainment value. This is when I – and countless others – re-watch Friends, or The Office, or Seinfeld.

Streaming services know this. That’s why they’ve been throwing around vast amounts of money to secure these legacy shows, or newer shows that have dominated the television landscape. According to The Hollywood Reporter, WarnerMedia’s yet-to-be-launched HBO Max spent billions of dollars for exclusive domestic rights (in the US) to all 12 seasons of The Big Bang Theory, just three months after the show’s finale. The show is now expected to be available when HBO Max launches in the spring of 2020.

That such a monumental deal would take place so early after a programme’s ending makes The Big Bang Theory somewhat of an outlier in the streaming wars. All of the other major agreements announced in the past few months have seen streaming services compete over series that ended a long time ago, whose fan bases have been consolidating for years. As Friends has been poached from Netflix, the streamer has landed the rights to Seinfeld for five years beginning in 2021. That deal reportedly cost up to $500m – but includes global rights (with some other deals being US-specific). Netflix knows it needs something to replace Friends and The Office, two shows that have proved incredibly popular for the service.

“Shows like Friends, The Office and The Big Bang Theory are great for streamers because they act as anchors that consumers can rely on when they get lost in the deluge of content that most services offer. You know what to expect from these shows and they are easily digestible,” says Frank Pallotta, a media reporter at CNN who regularly covers the streaming industry.

Shows like Friends, The Office and The Big Bang Theory are great for streamers because they act as anchors that consumers can rely on when they get lost in the deluge of content that most services offer. You know what to expect from these shows and they are easily digestible

“Also, despite spending millions to acquire these shows, they are safe bets for companies,” Pallotta adds. “Companies – like consumers – know what they’re getting with them: shows that were either highly rated or really beloved that have fan bases that will likely follow them anywhere. So it’s a smart strategy. Streamers need a cornucopia of content to reel in subscribers, and they can’t live off originality alone.”

The Big Bang Theory deal suggests that streamers are so faithful in this strategy that they might be willing to spend more, faster, as the competition for viewers’ eyeballs ramps up. But are enough people so desperate to watch Friends that they will sign up for HBO Max, a service that is expected to cost at least $14.99 a month?

Answering this question seems impossible right now. It has proved successful for Netflix in the past, but the new crowded landscape means every move now carries more risk. “It’s hard to figure out what exactly gets people to sign up for streaming services, but weirdly both originality and familiarity play a part,” says Pallotta.

“Look at something like Netflix’s The Politician. It’s a completely new creation but it’s from one of the most popular creators in Hollywood, Ryan Murphy. You may know nothing about The Politician, but you may know Murphy and that could be enough to get you to watch or even sign up.

“Shows like Friends or The Office – licensed content that are not new at all – are popular to binge. Why is that? Well, you can watch them while you eat, do work, fall asleep. They are background blockbusters. And, even though Friends has been off the air since 2004, it can be brand new for younger generations that didn’t watch it on TV, so that makes it alluring too even though it’s not new.”

The sums may be eye-watering, but the current trading season that has seen shows bouncing from one platform to the other has echoes of the past, according to Tim Hanlon, the founder and CEO of the Vertere Group, a media consulting and advisory firm based in Chicago, Illinois.

According to Hanlon, there isn’t much difference between the ongoing streaming deals, which are breathing new life into old shows, the way various programmes are syndicated by broadcasters in the US. The Big Bang Theory and Modern Family, for example, are both syndicated, meaning that they have aired in places other than their original networks (CBS and ABC respectively). In those cases, too, impressive amounts of money can be thrown around as syndication deals rival with streaming agreements. USA Network, a pay-for TV channel owned by NBCUniversal, reportedly paid around $1.5m per episode to syndicate Modern Family in 2010. TBS, a subscription network owned by WarnerMedia, is believed to have paid similar amounts for The Big Bang Theory.

“The whole television industry has historically been defined by a series of artificial distribution environments,” says Hanlon. “[There’s] television stations and cable networks and broadcast television networks. There’s all kinds of different sorts of embedded rules as to how programming gets distributed and sold and resold. It’s essentially trying to take the same assets and squeezing more revenue from it in artificially defined environments to maximise profit.

“The whole notion of this is predicated on [the idea that] content has value both when it’s originally released as well as over time in a whole bunch of different consumption settings. In many respects, everything old is new again.”

Shows like The Office are popular to binge. You can watch them while you eat, work, fall asleep. They are background blockbusters. Even though Friends has been off the air since 2004, it can be brand new for younger generations that didn’t watch it on TV

What can television history tell us, then, about the streaming wars’ possible outcome? According to Hanlon, viewers will grow increasingly savvy when it comes to navigating their subscription to various services and they will, of course, grow increasingly adverse to double-paying. Why would anyone pay to rent a film on Amazon Prime, for example, if it’s also available on Hulu, to which they have a subscription?

“It’s going to be a different experience for each consumer and every household,” Hanlon says. There will likely be a premium on user experience, and tools helping viewers discerning what content is already available to them are expected to be perceived as all the more valuable.

“I think that’s the crux of it: making it somewhat simple so that my television, my device recognises when I have subscriptions to and what I don’t so that I can work easily know what I need to do in order to get the stuff that I want,” he adds.

While some might be tempted to sign up for one or several new platforms as the market grows, Hanlon warns that there is a cap to how much someone is willing and able to spend on entertainment. For that reason, he believes that Neftlix, with subscriptions beginning at $8.99 a month in the US (and £8.99 in the UK), will remain a staple, followed by a second tier of must-haves such as Amazon Prime (which has the advantage of simply being an add-on to an existing Amazon membership), Hulu (perhaps Netflix’s oldest competitor on the streaming market) and Disney+ (which can count on mammoth names such as Marvel, Star Wars and Pixar).

Other services, including lesser-known platforms such as Pluto, Viacom’s free content platform, might follow. In parallel, consumers might also gravitate towards specific TV channels tailored to their tastes. “Consumers, households will be rebundling all of their own terms,” says Hanlon.

Hyper-customisation does seem to make sense in the face of a growing offer. Still, Pallotta points out, there’s a significant chance that consumers will end up “frustrated or really confused” as more streaming platforms go live.

“There’s so many services and so much content that it’s easy to get bogged down,” he says. “That’s why it’s important for companies like Apple, Netflix, Disney and WarnerMedia to market their products and have an ethos. What does this service offer that the hundreds of others do not? Who owns what? Who has my favourite show or my favourite brands? Those are the questions that streamers need to clearly answer for consumers.”

Friends, The Office and other “background blockbusters” may be the thing that makes the difference, for both older and younger viewers.

“Studies show that consumers are willing to spend around $40 per month on streaming”, Pallotta adds. “The battle to fit in the budget is the battle companies need to win. If not, even the most popular companies could find their services sinking into the streaming swamp.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments