Scurvy, lemons and the Sicilian mafia: Why natural resources are often a curse, not a blessing

What’s the link between lemons grown on an impoverished island at the foot of Italy, and a violent criminal organisation? Len Williams investigates

When Professor Ola Olsson, an economist at the University of Gothenburg, and his colleagues began investigating the origins of the Sicilian mafia, they noticed a curious pattern emerge in the data. During the mid-19th century, the newly minted Italian state conducted surveys of municipalities in Sicily to find out about crime on the island. Sure enough, in about a third of the island’s towns, reports of mafia activity came up time and again.

But why was the mafia present in some localities and not others? The economists began correlating the places where criminal elements were reported against other variables – from industry to mining to various agricultural goods. “The only significant positive association was in places with citrus groves,” says Olsson.

Lemon groves can only grow in certain altitudes and temperature ranges, so much of the Mediterranean island was not suitable for their production. Yet the economists found that everywhere that lemon groves could be grown, reports of the mafia featured too. What was the link between this innocuous fruit and a violent criminal organisation?

In a word, scurvy.

Until the late 1700s, long distance sailors were plagued by scurvy. The sickness causes tiredness, pain and bleeding gums. In severe cases it leads to personality changes and even death. However, doctors discovered that adding a small portion of fresh fruit to a sailor’s diet helped stave off the illness – thanks to the presence of vitamin C. In 1790 it became a policy of the Royal Navy that lemon juice be served to the entire crew on all its ships.

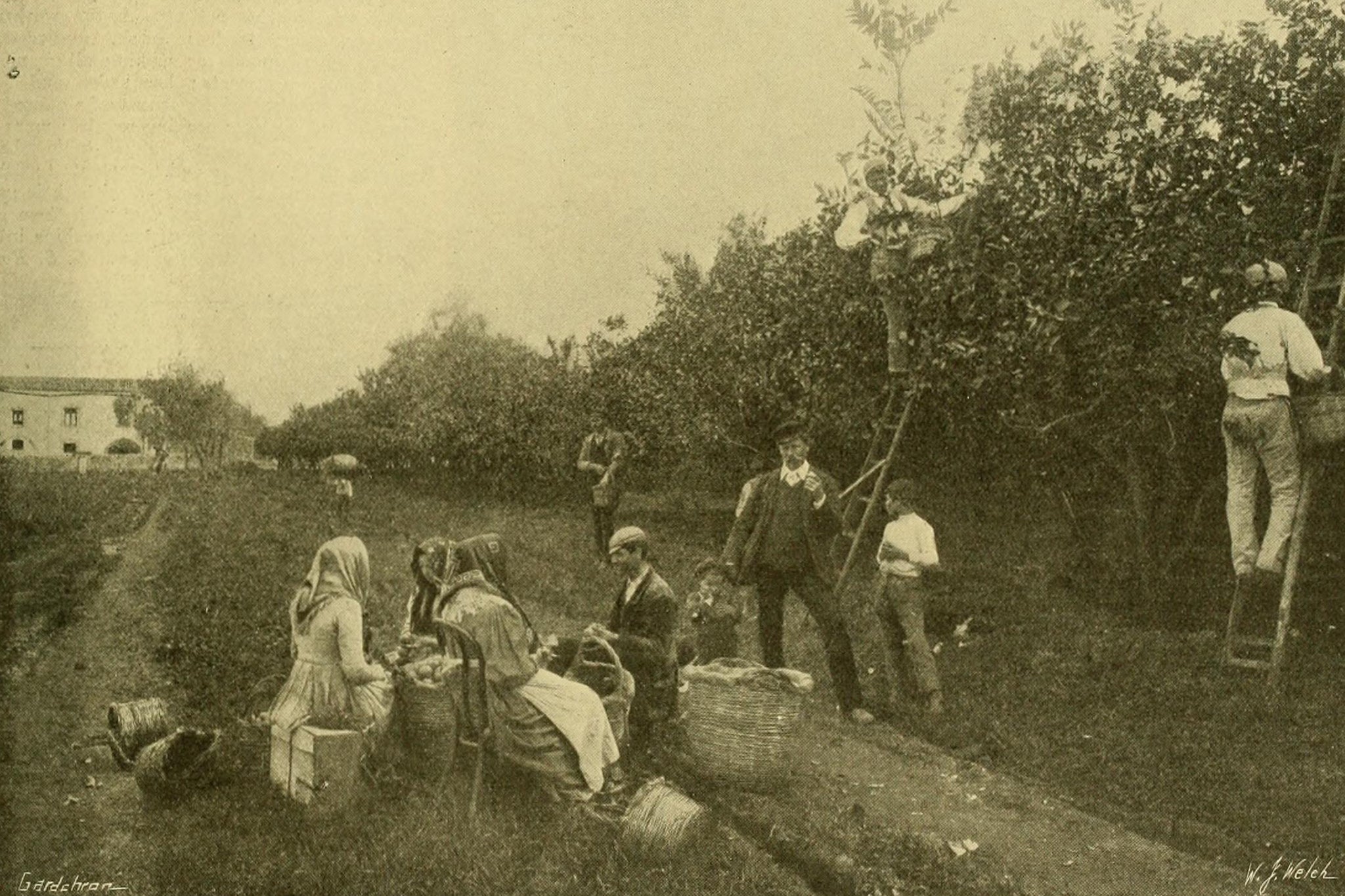

Demand for lemons boomed overnight. And one small, impoverished island at the foot of Italy was perfectly placed to capture this market. Sicily already grew some lemons for export (mainly for perfumes and decoration) and had the ideal climate for their cultivation. The discovery of lemons’ health benefits, and the fact the fruit stores well, meant citrus farmers found themselves sitting on top of a proverbial goldmine.

Unfortunately, it’s rather easy to steal lemons and many landowners found that a year’s crop could be stolen by bandits in a single dark night. Soon enough they began hiring local hardmen to protect their crops. Some of these thugs soon began offering protection to lemon farmers whether they wanted it or not. The Cosa Nostra was born.

If the link between the Sicilian mafia and lemon farming was a one-off, it would be little more than a quirk of history. However, in recent decades, scholars have identified a very similar pattern whereby countries that have an abundance of resources – be they minerals, oil or even certain plants – seem to become poorer and more chaotic as a consequence of the discovery. This phenomenon is termed the “resource curse”.

In the case of the DRC it appears that high commodity prices were typically associated with periods of increased violence

“There are many different manifestations of the resource curse and in truth it serves as a bit of an umbrella term that captures a number of theories,” explains Andrew Harris, of Fathom, an economics consultancy. “Of these theories, I think the most commonly cited is the Dutch disease hypothesis. At a basic level, this manifestation occurs when the discovery of raw materials in a country causes an appreciation in the value of a country’s currency. This appreciation occurs as sellers of the commodity will often want payment in the local currency for their own transaction needs and so the demand for this currency (and thus its value) rises.”

As a consequence, the country’s other exports will become more expensive to overseas buyers and the economy therefore loses its competitive edge. While the exporter of the good does well, everyone else in the country becomes poorer.

While a rise in poverty would be bad enough, the discovery of resources appears to compound other pre-existing problems and encourage violence. Fathom recently conducted a study of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to analyse this phenomenon in more detail.

“In the case of the DRC it appears that high commodity prices were typically associated with periods of increased violence. Looking at data on conflict-related deaths, our analysis showed that violence tended to increase during periods where the price of certain commodities were high or rising.” Fathom focused on cobalt, coltan, copper – all minerals that are present in our personal electronics, TVs and electric car batteries.

The discovery of a valuable new resource in and of itself does not automatically lead to violence and corruption. Professor Elissaois Papyrakis of Rotterdam’s Erasmus University has been investigating various manifestations of the resource curse over the past 20 years. He summarises the factors that need to be present to turn something that should be a windfall into a disaster.

“First you need to make a distinction between point source and diffuse resources.” Point source resources are things that are geographically concentrated such as oil or minerals, or that are just found in one place (like Sicilian lemons, which can only be grown at certain altitudes). The resources will therefore only be in the hands of a relatively small group of people who either protect it themselves, or have “protection” enforced on them by criminal gangs.

Papyrakis says the resource curse gets worse when a country has a relatively weak level of governance, poor rule of law, and a product that can be easily smuggled and stored. It also helps if the economy is otherwise relatively underdeveloped. A final factor to add to the mix is ethnic diversity, which can fan the flames of grievance. Why should we share the bounty of resources on our land with different groups in other parts of the country?

Looking at the case of Sicily, all these ingredients are present, says Professor Olsson. The first written mention of mafioso appears in the 1860s. This was a time where there was a high level of turmoil on the island, a weak rule of law and lots of uprisings against the Austro-Hungarian empire, which ruled Sicily at the time. “Throughout Sicily’s history there had been a long tradition of resistance to whoever ruled the island and this led to a culture of taking matters into your own hands,” rather than reporting criminals to the authorities.

And, just like other countries that suffer from the resource curse, Sicily experienced divisions between the various ethnic groups that had migrated to the island throughout its history.

There are many places around the world that have been wracked by violence and the emergence of armed criminal groups when demand for certain local resources suddenly explodes. Decades of turmoil in Colombia is driven, at least in part, by demand for coca leaves. Many of Afghanistan’s problems can be linked to the export of opium. And even the hipster-driven demand for avocado on toast has meant organised criminal groups have taken over control of the trade.

But perhaps one of the most intractable current cases of the resource curse is the DRC’s North and South Kivu regions. Mark Sheard, the CEO of World Vision UK, a charity, explains that the region is “rich with precious minerals and metals, such as coltan, which is used for many electrical devices, cassiterite, a primary source of tin, wolframite, which is used to make heavy machinery, and gold”.

In theory this abundance should make it one of the wealthiest places on Earth. However, Sheard explains that “the value of these resources has led to the rise of several armed groups which forcefully capture and control these valuable mining sites. This leads to poor governance of the mining sites and the labour, as well as the supply chains, allowing for the exploitation of these resources.”

This dependence on mineral resource means that many local people’s lives are marked by food insecurity and poverty, with children often forced to work in mines for a pittance. There is then a vicious circle whereby people living near the mines depend on them for income, rather than investing in activities that might be more profitable in the long run. This means communities cannot “diversify their income-generating activities, further exacerbating reliance on the natural resources”, Sheard explains.

What is more, their dependence on these resources exposes people living in these regions to the fluctuations in global commodity prices. During the pandemic, the collapse in commodity prices meant countries that depend on selling raw materials are further impoverished.

Professor Olsson notes that in political discourse, people behind violence in places like North and South Kivu are often described as rebel groups. However, many economists have argued they should really be considered as mafia groups, since their main purpose is to extract rents from resources.

The discovery of valuable minerals or demand for specific foodstuffs doesn’t always lead to an explosion in violence and poverty. Indeed, some countries that have found a wealth of resources have managed to escape the worst of this phenomenon.

A higher quality of governance can ensure that property rights (such as who owns a mine) can be better identified and enforced

Why, for instance, did tiny Norway, which discovered huge offshore oil reserves in 1967, avoid descending into chaos, while countries like Venezuela or Nigeria have been damaged by the experience? Or why did Botswana, which is the world’s second greatest exporter of diamonds avoid the “blood diamond” violence that ravaged many other Sub-Saharan African countries?

In part, countries that avoided the resource curse were just lucky. Professor Olsson points out that Botswana already had a functioning democracy in place before its diamond wealth was discovered. It is also a fairly ethnically homogeneous country – the Tswana people are by far the largest ethnic group there. As a result, there was far less risk of grievance about how the bounty from this resource would be divided up.

Besides the pre-existence of a democratic and functioning government, Professor Papyrakis also notes that countries like Norway already had a relatively developed and diversified economy before the discovery of oil. This meant that Norwegians did not suddenly become dependent on oil for all their income, but could instead invest it wisely (Norway now has one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds).

But what can be done for countries that are already suffering from the resource curse? What should be done to prevent the emergence of organised crime groups like the mafia in countries that already have weak governance and poor rule of law?

“Most of the literature will probably tell you that, as with most things in development economics, it’s all about institutions,” says Andrew Harris of Fathom. “A higher quality of governance can ensure that property rights (such as who owns a mine) can be better identified and enforced. The problem is that it’s not clear to me that there’s an easy way of achieving this”.

Nevertheless, various initiatives have emerged that try to tackle the problem. For instance, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative was set up in 2003 and aims to improve transparency and tackle corruption in countries with natural riches. One of its mechanisms is to ask companies extracting minerals to publish how much they paid the local government in tax. The government also publishes what it received.

The aim here is to tackle corruption by ensuring that money isn’t being squirrelled away into an offshore bank account by politicians and officials. If people know that all the bounty from resource extraction is going into the government’s own coffers, they can be more confident it will also be redistributed fairly. That breeds less resentment between groups, and means there’s less incentive for violence.

In the DRC, World Vision is taking more direct action through an initiative called the Partnership Against Child Exploitation (Pace) which Sheard says is designed to empower children and communities to raise awareness of their rights. Among its activities, Pace aims to raise awareness among local communities of alternatives to child labour (such as education), strengthen legal and policy environments and improve supply chain due diligence.

I went on holiday to Sicily a few years ago and, at the end of a night out, found myself on a takeaway’s terrace eating a slice of the island’s characteristic deep pan pizza. Groups of young people were sat at plastic tables devouring pizza slices and arancini, laughing and telling tales in the warm night air. All of a sudden, a hush fell over the terrace when an older man, all dressed in white, sat down and began drunkenly holding forth. I turned away for a moment but when I looked back, all the young people were quickly leaving the square in silence.

Whether or not the white suited man was a mafioso I’ll never know, but the fear in the air was palpable. To think that after almost 200 years, a criminal organisation that emerged from the demand for lemons continues to have such a hold on the popular imagination is shocking. Other countries which are struggling with similar kinds of resource curse today can only hope to avoid the same fate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments