Murder in Munich, 1972: How the ‘cheerful’ Olympics went sour

Fifty years ago, the summer Olympics were held in Munich. The event will always be remembered for the massacre of 11 Israelis by the Palestinian group Black September. Former athletics correspondent Pat Butcher was there at the time

It was ridiculously easy to get into the Munich Olympic athletes’ village in 1972, even after the murderous incursion by Black September guerrillas which resulted in the deaths of 11 Israelis, a German policeman, and five of the terrorists. No one, it seems, least of all the Bavarian police or any of the West German authorities, had prepared for anything like the attack. The emphasis was on emulating Tokyo 1964, and seeing Munich as the ultimate exercise in rehabilitation for the leading member of the Axis powers a quarter of a century after the Second World War. And in Olympic terms, the Germans needed to exorcise the memory of the 1936 Games in Berlin which, despite African-American Jesse Owens’ best efforts (a four gold-medal affront to Hitler’s dreams of Aryan supremacy), remained a display dedicated to greater Nazi glory.

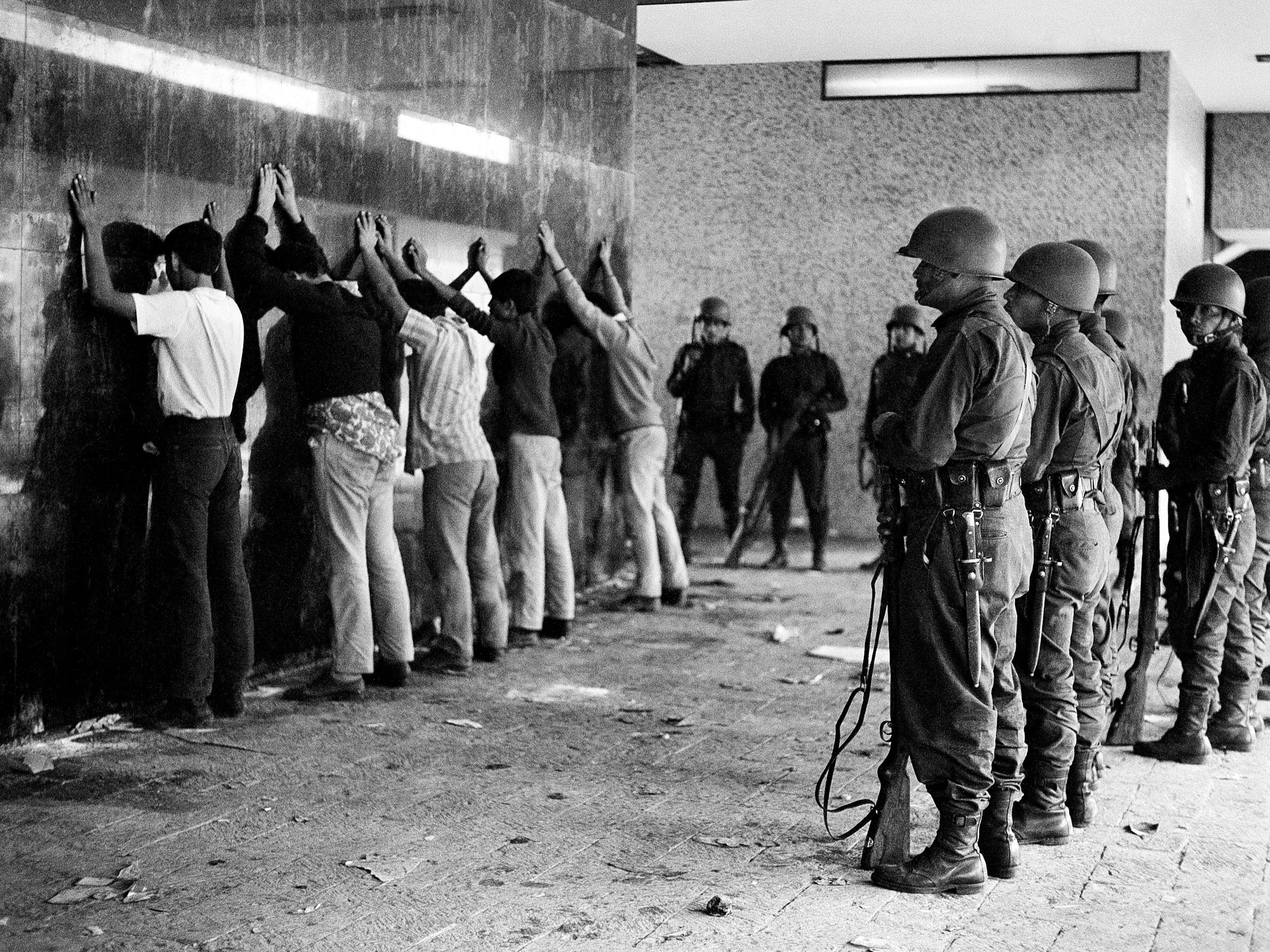

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) might also have expected that bringing the Games back to Europe from a volatile Latin America would have a stabilising effect on the institution. But it wasn’t just the events of Mexico 1968, both in and out of the stadium, that should have alerted the IOC and the German authorities to the possibility of unrest. Bob Beamon’s stratospheric long jump and the black-power salute of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 200 metres medal ceremony are probably the best-remembered events in the stadium; but the 1968 Games were marred before they even began, by assassinations which still resonate in Mexican society and politics more than 50 years later. Student unrest was worldwide in 1968, but in Mexico it became focused on the soaring costs of the Games in a country where privation was widespread, with assassinations of student and labour leaders by right-wing groups or the military itself.

What became known as the Tlatelolco Massacre was a watershed moment. On 2 October, 10 days prior to the Olympic opening ceremony, a peaceful march of around 10,000 to the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco area of Mexico City ended in bloodshed. The numbers of dead are still contested today, but when the 70-year regime of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) came to an end in 2000, government and military documents on the events finally began to seep out. The original and official account had always been that protestors had fired on the heavily armed forces, which assembled around and sealed off the plaza following the march’s arrival. But testimony collected in the days and weeks immediately after the massacre by Franco-Mexican journalist Elena Poniatowska, for her seminal work, La Noche de Tlatelolco (translated as Massacre in Mexico), proved far more credible. It is now accepted that up to 400 people were shot or bayoneted to death, and that the instigators of the massacre were members of the specially recruited Olympia Battalion, who were in civvies but wore white gloves or handkerchiefs to distinguish themselves to their uniformed colleagues in elevated sniper positions around the square.

But the Games themselves had always been sacrosanct in the strictest sense. The Ancient Olympics were a religious festival, dedicated as much to art – poetry, drama, sculpture et al – as to sport, but it is the athletics (and wrestling, both much featured on pottery) which endures; and to ensure universal participation for a population that stretched from the Black Sea to the Atlantic, taking in parts of north Africa, there was an Olympic Truce, which the fractious warring states in the Hellenic world observed, well, religiously. And although politics permeates the Olympic movement to this day, and the Black Power salute in Mexico had been an obvious reminder, physical interference in the modern Olympic Games was an unwritten prohibition.

So no one was expecting an attack on the Games themselves. Nevertheless, in the wake of Mexico City, events closer to home should have alerted the German authorities to the possibility of an attack in Munich. The Six-Day War in 1967 had further destabilised a febrile Middle East; and the takeover of East Jerusalem by the victorious Israelis had convinced Palestinians that they were even further away from justice for the expulsions from their land following the creation of Israel 20 years earlier; and that now their only avenue was violence on an international stage.

Black September, so named after the month of expulsion of Yasir Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organisation from Jordan in 1970, was only the most recent avatar of the multiple Palestinian groups dedicated to combatting/overthrowing the Israelis. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) had become the best-known group post-1967 for its multiple aircraft hi-jackings, featuring the first celebrity terrorist, Leila Khaled. For several years, the photo of a kaffiyeh-clad Khaled carrying an AK-47 became as iconic as the bearded and bereted Che. Khaled allegedly underwent a half dozen sessions of plastic surgery to enable her to carry out further attacks unrecognised, the (unsuccessful) last of which saw her temporarily jailed in, of all places, Ealing in west London. Already in 1968, the year of the Mexico City Olympics, the group had hi-jacked El-Al planes in Italy and India, and downed a Swissair jet carrying 47 passengers, on the way to Tel Aviv.

Four years after the sordid events of Tlatelolco, and 36 years after the Hitler Olympics, the velvet glove was the order of the day in Munich

In 1970, they hi-jacked planes from TWA, Pan-Am, BOA and Swissair; three of them were detonated at Dawson’s Field, a former British military airport in Jordan. It was this event which finally provoked King Hussein to get rid of his increasingly unruly and unwelcome guests. He launched his own murderous attack on the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, forcing the exile of the PLO (to Lebanon), and providing the pretext for the birth of Black September.

But as far as Germany was concerned, in addition to there being huge numbers of Palestinian workers and students in the country, many of whom openly supported action against Israel, there were sufficient incidents early in Olympic year to alert the authorities. Members of Black September killed five Jordanians near Cologne in February 1972, allegedly for being traitors. Later that month, a device exploded in a Hamburg factory, which made electrical equipment for Israel; then a Lufthansa plane was hi-jacked, resulting in a payment of a $5m ransom.

Nevertheless, four years after the sordid events of Tlatelolco, and 36 years after the Hitler Olympics, the velvet glove was the order of the day in Munich. This was personified in Chancellor Willy Brandt who, despite doubts at home, was an icon for pacifism abroad. Brandt, born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm, was the text-book anti-Nazi. Escaping to Scandinavia in the early 1930s, he used the pseudonym to escape detection. Following the war, he formally adopted his alter-ego, appropriate perhaps for someone who adroitly trod the tightrope between alignment with the US, which offended the left, and his policy of Ostpolitik, better relations with the East, which enraged the right. Whatever his critics at home thought, international recognition for Brandt’s achievements came when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the year before the Munich Games.

That was the year that I was in the best form of a fairly mediocre running career – a bronze medal in the AAA indoor championships in the little run (indoor) steeplechase, ie no waterjump, and I harboured delusions I might make the British team for Munich. Those dreams were dissipated by poor form months before the Games, and I never even got to the selection trials. I was into my running and some of my competitive acquaintances were selected in the British and Irish teams, so I resolved to go to Munich anyway.

I’d been sharing a house in north London with a couple of students from Bavaria, and one of them invited me to stay at her parents’ house in Dachau, a 30-minute S-Bahn ride from Munich; I spent a couple of days and a night sleeping in a hay bale, hitching south to the Bavarian capital. The infamous concentration camp, the first in Nazi Germany, is four kilometres east of the town of Dachau, whose first 1000 years of history were relatively unremarkable, save for the creation of a distinguished colony of painters in the late 19th century. Nowadays, it is a thriving commuter town of around 45,000 inhabitants, who have doubtless got used to apologising abroad for the misappropriation of their township name. Its recent baleful history would soon be widely referenced again following the Munich Games.

The terrorists were even helped over the fence by athletes returning from a night out to their quarters by the shortest route

The first time I went to the warm-up track behind the Olympic Village, a couple of days before the opening of the Games, I watched former New Zealand international runner Bill Baillie just stroll through the gates past the guards. They took his All-Black blazer for sufficient ID, since he didn’t have what has become the indispensable photo badge on the lanyard swinging back and forth on his chest. Some Kiwi athletes, spotting his bold move, barracked him from the balcony of their nearby residence. He waved at them nonchalantly, and the guards took no notice whatsoever.

Since I was wearing a tracksuit and a sheen of sweat from a lap or two around the warm-up track, I essayed running through the gates. Again, not a problem! But I surmised that wasn’t going to work every time, so I resolved to look up those acquaintances on the British team, and see if any of them was prepared to “lose” their ID card. The first two I tracked down gave me short shrift, although one of them did concede that if I was fortunate enough to find a willing accomplice, there was a spare room in his designated apartment where I could crash overnight should I not want to go back to Dachau.

A few minutes later, I bumped into Dave Bedford, Britain’s then best long-distance runner but better known in recent years as the long-time boss of the London Marathon (lately retired). During his running career, Bedford was widely loved as much for an obvious ‘devil-may-care’ attitude, exemplified by red running socks and regular run-ins with the national athletics authorities, as for his cavalier racing tactics. Apart from his distant victories, his most newsworthy stunt prior to Munich had been to shoot a team colleague in the backside (from a distance) with an air-gun, at a pre-Olympic training camp in the Alps. Bedford recognised me from events we had contested at RAF Cosford, which housed the UK’s only indoor track at the time. When I explained my predicament, he simply took the ID card from around his neck, and gave it to me. He halted my profuse thanks, saying dismissively: “They’ll expect me to lose it anyway.”

The balmy Bavarian weather, the general laid-back atmosphere, the superlative competition and the appreciative audience in what, in the case of athletics, later became the long-time Bayern Munich football stadium, made the opening days a huge success. Mark Spitz and Olga Korbut distinguished themselves as the competitive heroes of the Games, he with his seven gold medals in the pool (finally one-upped by Michael Phelps in Beijing 2008), and she by her elfin exuberance on the gymnastic equipment, enthusiastically willed on by a legion of lustful male TV commentators.

The Cheerful Games (as it had been designated) went sour in the early morning of 5 September. The Israeli delegation had originally asked to be housed at the top of one of the main tower blocks in the middle of the Olympic Village but were allocated a low-rise building with no additional security and perilously close to the perimeter fence, which was easily scaled by the Black September commando at around 4.30am in the middle of the second and final week of competition.

Zamir and Cohen prevailed on the Bavarian police to let them try to talk to the terrorists, but when they climbed on top of the terminal building and started shouting in Arabic, the Palestinians opened fire on them

The terrorists were even helped over the fence by athletes returning from a night out to their quarters by the shortest route. The American athletes took the Palestinians for fellow competitors since they were wearing tracksuits and carrying sports bags (laden with weapons). Having bid farewell to their brief acquaintances, the eight guerrillas broke into several apartments in the Israeli quarters, and almost immediately shot and killed Yossef Romano and Moshe Weinberg, both of whom had tried to resist. Several team members, alerted by the shouts and gunfire escaped by various routes, but nine hostages, all male, were taken – David Berger, Ze'ev Friedman Yossef Gutfreund, Eliezer Halfin, Amitzur Shapira, Mark Slavin, Andre Spitzer, Jakov Springer and Kehat Shorr.

There followed 24 hours of negotiation with the unprepared local authorities, while TV cameras were transferred from use in the stadia to being trained on the Israeli quarters. The doyen of BBC TV commentators, David Coleman, put on a commentary tour de force, holding the mike behind a static camera image of the occupied building for the best part of a day. Mindful of the abiding notion that, as one of my editors once reminded me, “Sport is the toy town of newspapers”, Coleman, a long-time newsman himself, gave witting corroboration when he later said, “That’s when I had to be a real commentator.”

The terrorists demanded the release of more than 200 Palestinians and sympathisers from jail in Israel, in addition to the liberation of Red Army faction leaders, Ulrike Meinhof and Andreas Baader, from German custody. Israel’s response was immediate and in line with their declared policy on non-negotiation.

Meanwhile, Olympic competition continued, as did life in the village. Reminiscing over a decade ago with Welshman Lynn Davies, the 1964 Olympic long jump champion who was UK team captain in Munich, he recalled: “People were playing table tennis in the square, while 200 metres away, the Israeli athletes were being held at gunpoint. It was surreal.”

For those few score athletes who were interested in the stand-off, and were gathered as close as they were allowed to the Israeli quarters, there were dissenting voices. I heard an Irish athlete yell out: “Golda Meir holding the world to fucking ransom again.”

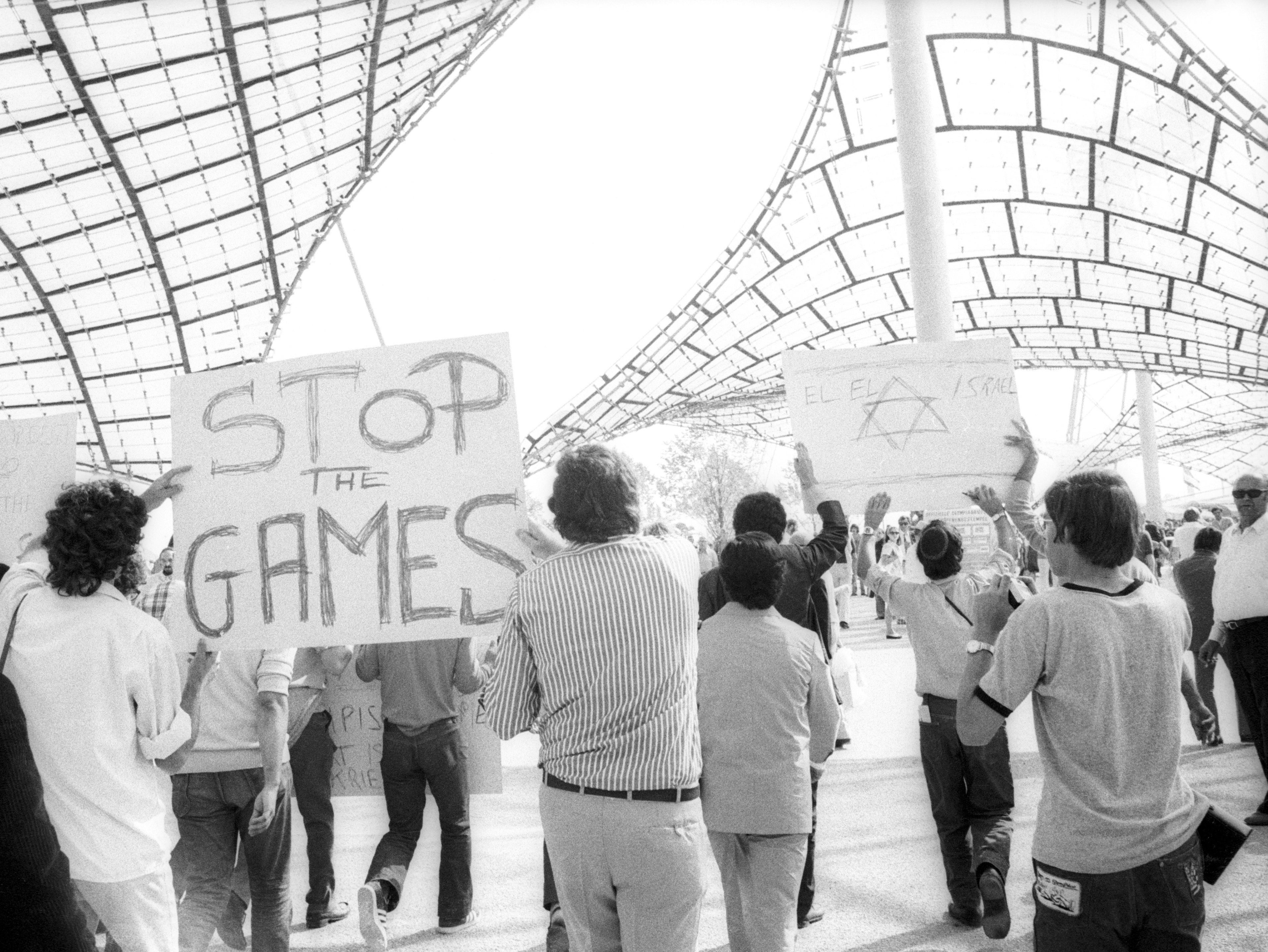

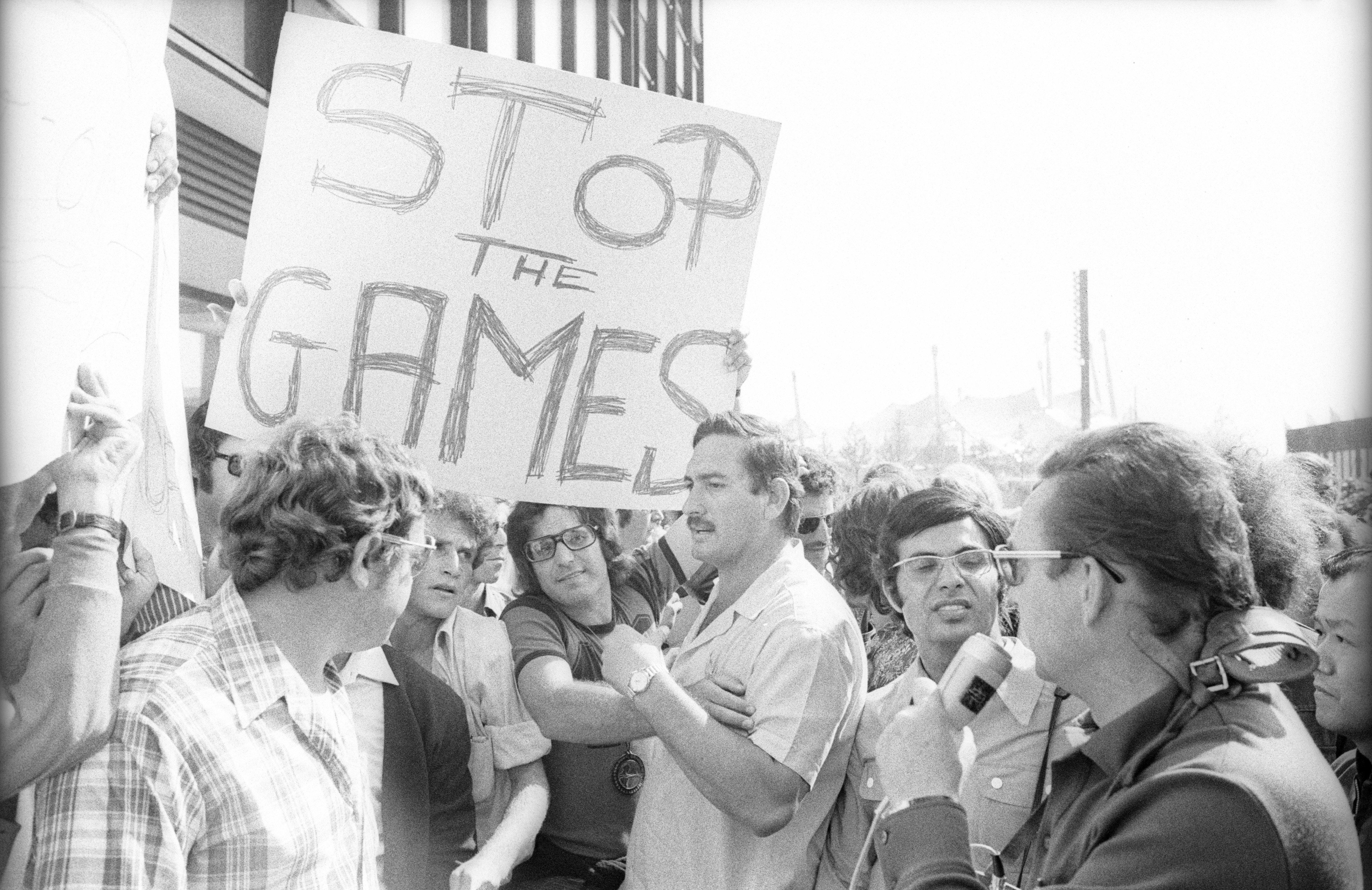

In the wake of mounting criticism of the conservative IOC and its ultra-conservative head, American Avery Brundage, competition was finally halted late afternoon on 5 September, over a dozen hours after the initial incursion by Black September. After several deadlines set by the terrorists came and went, it was agreed that a bus would be provided to take the Palestinians and their captives to the helicopters, which would fly them to Fűrstfeldbruck military airport where a Boeing 727 was to take them to Egypt.

The terrorists had chosen Cairo, a factor which became evident when Brandt tried to call Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, to get him to intercede. Sadat refused to take the chancellor’s call; like the Jordanians before him, Sadat wanted nothing to do with the Palestinians. With little adequate training for such a scenario, a team of poorly positioned snipers at the airport tried to abort the departure. The outcome was carnage. Five of the terrorists were killed, but not before one of them exploded a grenade killing all the captives. A German policeman, Anton Fliegerbauer, was killed in the shoot-out. Three weeks later, in response to another hi-jacking, of Lufthansa flight 615, the three surviving terrorists – Adnan Al-Gashey, his nephew Jamal Al-Gashey, and Mohammed Safady – were released, and flown to Libya, where the bodies of their dead colleagues had been sent.

People were playing table tennis in the square, while 200 metres away the Israeli athletes were being held at gunpoint. It was surreal

The rescue attempt and its aftermath had been a disaster from start to finish. Certainly, the cell structure of Black September, an innovation for a PLO grouping, as opposed to a centralised command, ensured that any prior intelligence of the attack was absent; but another crucial impediment was the nature of postwar German government. The imposition of federalism by the Allies was to ensure that power could never again be centralised, a system from which Hitler and the Nazis had benefitted (a political system, incidentally still extant in the UK).

But in Munich 1972, it meant that national politicians, including Brandt, had to stand aside and let the Bavarian police and politicians deal with the situation. And the Munich police had already gained a reputation for being trigger-happy and incompetent. Several domestic incidents in the late sixties and early seventies had ended in innocent people being accidentally killed by the local police. And something as simple as failing to identify the number of terrorists, thought to be five, even when eight of them emerged from the Israeli quarters to board the bus which would relay them to helicopters and thence to Fűrstfeldbruck meant that there were only five police snipers waiting for them at the airport.

Even worse, the snipers were untrained, and had simply been chosen because they shot competitively outside of police duties; and in any case, they only had standard-issue rifles without either telescopic or night-sights. Nor did they have walkie-talkies, something that every steward in the Olympic village possessed. Their anarchic distribution around the airport buildings meant that in the fire-fight, one of them was shot in the backside by a colleague.

Standing, watching all of this impotently, were two of the most practised anti-terrorist experts in the world. Zvi Zamir was the head of Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, and an authority on counter-terrorism. His colleague Victor Cohen was the most experienced Israeli terrorist negotiator. When news of the hostage-taking had reached Israel early that morning, the pair had taken the first available flight to Munich. Their experience and expertise were going to be refused or ignored throughout the tragically incompetent rescue attempt. Quoted in One Day in September, Simon Reeve’s companion book to Kevin MacDonald’s lauded documentary of the same name from 1999/2000, Zamir said: ‘There was no rescue plan, no preparations, nothing whatsoever. There were no lights on the helicopters, I mean, there was just nothing. I couldn’t think of a better place (to succeed) because it was an open area.”

Zamir and Cohen finally prevailed on the Bavarian police to let them try to talk to the terrorists, but when they climbed on top of the terminal building and started shouting in Arabic, the Palestinians opened fire on them. “Their reply was clear,” said Zamir. “This was the end of the Israeli people in the helicopters.” And so it proved.

It had originally been reported in Israel that Ladany had been one of the victims, but he was very much alive. He seemed to be getting off on it

What made the disaster worse for waiting Israelis was the false dawn announced at the gates of the military airport when the shooting finally stopped. Someone who has never been identified but who was wearing an Olympic official’s hat went to the assembled press and public waiting outside the airport and announced that all the hostages had survived. News agencies sent out a snap communique at 11.31pm local time – ‘ALL ISRAELI HOSTAGES HAVE BEEN FREED’! With just one hour time difference to the Middle East, special editions of the Jerusalem Post went on to the street with the banner headline – ‘HOSTAGES IN MUNICH RELEASED – ALL SAFE AFTER GERMANS TRAP ARABS AT MILITARY AIRPORT’. The ecstasy wasn’t going to be deflated for close to four hours. At 3.17am on 6 September, Reuter issued a correction – ‘FLASH! ALL ISRAELI HOSTAGES SEIZED BY ARAB GUERRILLAS KILLED’.

The resumption of the Games several hours later could hardly have been handled worse by Brundage. An Olympic competitor in 1912 in Stockholm, where he finished way behind his US colleague, native American Jim Thorpe in the pentathlon and the decathlon, Brundage was a self-made millionaire who took amateurism so seriously he refused expenses from the IOC and funded his own worldwide travels to meetings.

History has not treated Brundage kindly. An avowed admirer of the Nazi re-organisation of Germany in the 1930s, and a rabid anti-communist, he nevertheless eventually conceded that it made little sense to accept Nationalist Taiwan rather than the People’s Republic as the representative of China (another example of the international political game the IOC has to play). Yet, given the extensive boycotts which were to follow and mar the next three Games, Montreal, Moscow and Los Angeles, the exclusion of Rhodesia from Munich following UDI with its explicit apartheid policy was small beer. But it irked Brundage. The fact that he gave the Rhodesian exclusion equal mention with the Israeli killings in his address to a packed stadium on 6 September, just a few hours after the tragedy, incensed many more people. The crowd may have applauded his “the Games must go on” appeal, but his rudely reductive political speech was widely abhorred. An Irish team manager I accompanied out of the stadium implied that one of the terrorist bullets might have been better used on Brundage.

Yet even those directly involved with the tragedy agreed that the Games should continue. Interviewed for MacDonald’s documentary One Day in September, Shmuel Lalkin, the head of the Israeli delegation in Munich, said: “Personally, I think the Games should have continued, otherwise you give in to the terrorists.” Roone Arledge, long-time head of the US television network ABC, which was largely funding the Games, concurred. “I think most people agreed that the Games shouldn’t be called off, but it did seem like it was brushed off very quickly and business as usual.”

Interviewed by Eric Rouleau for the latter’s book My Home, My Land, Abu Ilad, one of Black September’s inner circle, said: “We were obliged to note with considerable sadness that a large segment of world opinion was far more concerned about the 24-hour interruption in the grand spectacle of the Olympic Games than it was about the dramatic plight endured by the Palestinian people for the past 24 years or the atrocious end of the commandos and their hostages.”

Back in the Village, I kept coming across one of the survivors of the massacre, 50km walker Shaul Ladany, giving interviews to international TV and radio stations. It had originally been reported in Israel that Ladany had been one of the victims, but he was very much enjoying being alive. After the second or third time I heard him say that even as a walker he probably broke the 100 metres world record in running away from the Palestinian guns, I began to find his effusive commentary mildly offensive. He seemed to be getting off on it; it had become a performance. I later learned that Ladany had survived the holocaust; as an eight-year-old in Bergen-Belsen, his family was part of group ransomed by the US. Two months after Munich, he returned to Europe and won a world title in Switzerland.

The biggest problem with my “borrowed” ID card should have been that I looked nothing like Dave Bedford. The only concession to any vague similarity was that he’d recently had his long ropes of hair cut off, but he’d got a jet-black crop whereas mine was ginger; and while I was clean-shaven, he had a Zapata moustache.

In all the times I went in and out of the Village, even after the massacre, no one looked closely enough to detect the obvious difference. And the final occasion was the most extraordinary.

Following the muted closing ceremony, I went for a drink with friends somewhere near the warm-up track at the back of the Village. Following the massacre, all but the main gates to the Village were closed early, and when I left the bar late, I had a couple of kilometres diversion to get to the front gate. With either the insouciance of youth or the crass stupidity of the inebriated, I approached the guard on the inside of the back gate, proffered my fake ID and since I spoke little or no German and he no English, I indicated I might climb over. He nodded instantly, and I began to clamber over the roughly eight-foot high gate. While I was astride the top, a squad of the soldiers who had been introduced after the massacre marched into view, doing one of their security rounds of the Village. I froze on top of the gate, suddenly very sober, but seeing the guard waiting for my descent, the troop never even broke stride, and were soon gone.

Three delegations – Egypt, Algeria and Philippines – left Munich early, along with several individual competitors. Jos Hermens was the Netherlands’ equivalent of Dave Bedford, another long-distance runner whose obsessive and excessive training resulted in world records prior to enforced retirement due to extensive injuries. Hermens is now head of one of the world’s most successful athletes’ agencies. He had competed in the 10,000 metres earlier in the Games, but left before the 5000 metres’ final. Apart from flying visits, neither Hermens nor myself, now an established Fleet Street athletics writer, had been back to Munich until the European Championships there in 2002. An Israeli team was also there since, for continuing political reasons, they are not accepted in Asian competition.

On the final day of the championships, there was a ceremony of remembrance, attended by survivors of the attack, and by relatives, wives and children of the assassinated. Few will have noticed the strategically placed scarf on the stone memorial to the dead, covering the name of the German policeman who perished. “It’s quite simple,” said Hermens after the ceremony, “we were invited to a party, and someone comes to the party and shoots people, how can you stay?”

Hermens was also scathing about Brundage’s speech. “He never mentioned the Israelis the day after. I was literally sick; I threw up in disgust.” But he was one of the few; athletes have a way of compartmentalising events which don’t fit into their worldview, which is to say, training regimes. I suspect that, had Tokyo 2020 not been postponed, many athletes would have been prepared to go and risk their own safety; and the lives of others. Indeed, that’s exactly what did happen when the Games were held a year later – against the wishes of a majority of Japanese, according to opinion polls – in the middle of another upsurge in the pandemic, in July/August 2021.

Pat Butcher is an author and a former Fleet Street athletics correspondent for 30 years. His latest book is ‘Quicksilver, The Mercurial Emil Zátopek’; available here at GlobeRunner

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks