Munich massacre: the Olympics’ darkest day revisited

In 1972 in Germany the Olympics were violently thrust into the world’s headlines for all the wrong reasons. James Rampton on a new documentary that recalls a bloody terror attack

An 85-year-old man in a turquoise T-shirt with the logo “Jerusalem Marathon 2011” sits in his front room beside an enormous cabinet full of sporting trophies. An ex-Israeli athlete, he is hunched at the table over a fading black and white photo of his former team-mates. Slowly, but surely, he points to the faces on the picture, reciting their names as he goes: “Weinberg, Friedman, Springer, Amitzur Shapira, Yossef Romano, Ze’ev Halfin.”

These are the opening scenes of a new documentary called Terror, and the man is Shaul Ladany. He is one of the survivors of the Munich massacre, the appalling terrorist atrocity that took place at the 1972 Olympic Games. With a bitter irony, before that terrible moment, they had been dubbed “The Happy Olympics”.

The faces and the names Ladany is remembering are some of his colleagues who fell during the attack. The Olympics have faced many exceedingly tough moments over the centuries, and indeed they are about to confront one of their most testing challenges this summer in Tokyo by staging a games that has been severely affected by Covid-19. However, the Munich massacre is still remembered as the darkest day in the history of the Olympics.

At 4.30am on the morning of 5 September 1972, eight Palestinians from the Black September terrorist movement stormed the apartments of the Israeli delegation. Targeting specific apartments, they immediately shot dead two members of the team and took nine others hostage.

Ladany, who was at the 1972 Games representing Israel as a long-distance race-walker, counts himself extremely fortunate that he was not killed or captured by the attackers, too. “In the end, I was lucky that the terrorists had raided units 1 and 3, but not 2 where I slept. It later turned out that the terrorists knew where each of the athletes was staying. My unit housed two marksmen competitors, and they didn’t want to take the chance that the athletes had their rifles in the rooms.”

After he had been woken by the screams of his colleagues in other apartments, Ladany was the first person to sound the alarm. He leapt from the second-storey balcony of his room and escaped to the American dormitory. There he roused the US track coach Bill Bowerman and told him about the attack.

All the hostages and five of the eight Black September members were killed during the calamitous operation to rescue them. A West German policeman also died in the crossfire

As the hostage situation unfolded on screens around the planet – for the first time ever, the 1972 Olympic Games were broadcast live on television – the Palestinian cause grabbed the world’s attention.

The Black September leader Luttif Afif called for the release of 234 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails and the West German-held founders of the Red Army Faction, Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof. He also demanded that his cell should be given free passage to Egypt.

When the hostages were transported by helicopter to the nearby Fürstenfeldbruck airport, the West German authorities launched a failed attempt to rescue them. All the hostages and five of the eight Black September members were killed during the calamitous operation. A West German policeman also died in the crossfire.

The fact that this slaughter of Israeli citizens took place on German soil – where less than three decades earlier, unthinkable horrors had been visited upon the Jewish people – only made the Munich massacre more shocking. These dreadful events still cast a long shadow over the Olympic movement.

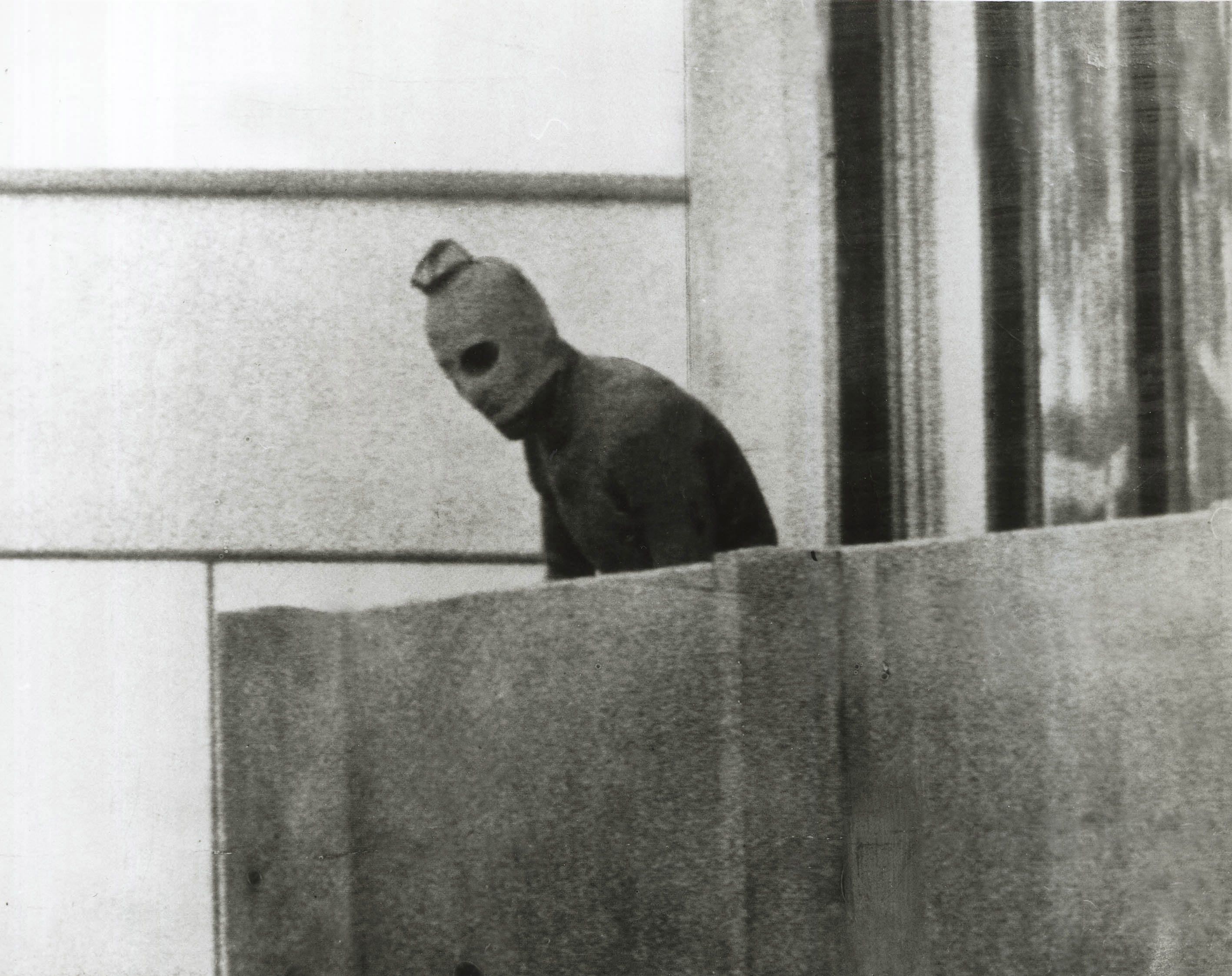

The photograph of a Black September terrorist in a balaclava looking out over the balcony of an Israeli apartment remains an iconic and haunting image of the day the Olympics were violently thrust into the world’s headlines for all the wrong reasons.

The story did not end there, however. There was an astonishing coda to the atrocity. The livid Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, would not let the terrorist outrage stand.

She ordered Operation Wrath of God, which authorised Mossad to track down and assassinate the three surviving Black September perpetrators of the massacre. The operation was subsequently recounted in Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-nominated 2005 film, Munich.

Ladany has had a quite extraordinary life. Born in Belgrade in then Yugoslavia in 1936, as an eight-year-old he survived six months in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. After the War, he ended up in Israel, where his life story took another remarkable turn. He became professor of industrial engineering and management at Ben Gurion University, has written over a dozen books and 120 scholarly papers, and mastered nine languages.

A two-time Olympian, Ladany is also a highly accomplished athlete. He won the gold medal in the 100km race at the 1972 World Championships and, half a century after setting it, he is still the world record holder in the 50-mile event.

Looking back on the Munich Olympics, he recalls his initial delight at being chosen for his second games. “I was very proud that I had been selected again to represent Israel at the Olympics. It was special because the Olympics were held in Germany.”

After the massacre, he was overcome with fury about the death of his colleagues. “Of course, I was angry. Maybe that’s putting it too mildly. I was angry that the terrorists had killed Israeli athletes and my teammates. Very angry, shocked.

“There was something else. They had changed the Olympic Games forever. In ancient times, violence was taboo during the Olympics. The Olympic Games are a sports event. Violence has no place there.”

In the past, “wars would be interrupted to allow the Olympic Games to take place. The Arab terrorists had killed that thought, that Olympic ideal of brotherhood.”

Robert Oey, the Dutch filmmaker who produced “Terror” with Jorinde Soree, chimes in that this politicisation of the Olympics is what still enrages Ladany above all else. “Because he is so straightforward and is a sportsman, the thing he hated the most was that there was this one moment every four years when the people of this planet did only one thing, and that was compete on a sporting level, but Munich made that particular moment in time political. It politicised a sporting event, and the Olympics have never been the same again.”

The quality which emerges most strongly from observing Ladany is his matter-of-fact, but almost invincible will to survive. Talking to The Independent from his office in Amsterdam, Oey says: “What you see with a lot of survivors is the joy they take in living. It’s like the wish to stay alive, the wish to survive is bigger than anything else. So Ladany was doing the interview with us when he suddenly said, ‘I have to go now’.

“When we asked why, he replied, ‘I have to to go for a run’. Where? ‘I don’t know, but I just have to run.’ His passion in life is running, and of course we as filmmakers want to make that more poetic. So we think the running is a metaphor for something. But if you confront him with this, he looks at you like, ‘what are you talking about? I just like running’.”

The producer of the documentary, which goes out at 7.35pm on PBS America on Thursday, adds: “Ladany is very down-to-earth. Perhaps the fact that he survived was due to the simplicity with which he approached life.”

It was a heinous act of violence, but the Munich massacre achieved one aim: it made the whole world take notice of the Palestinian cause. Oey says: “They wanted a platform, they wanted the world to know about their struggle and they certainly did that. They put it on the agenda.”

Expanding the discussion, Oey says that terrorism can sometimes attain its objective of suddenly shifting the world’s gaze on to a single cause. For instance, “9/11 showed our vulnerability. It showed that we as western nations are fallible, that we are very vulnerable and very afraid. It may even have achieved something that we don’t dare to look at. Did we cause the hatred that is so alive among some nations?”

For all that, the producers of Terror are quick to point out that in no way do they support terrorism. According to Soree: “In this series, we’re trying to explore all the different perspectives. When we look at things from the perspective of the attacker, it doesn’t mean that we agree with the attack per se.”

People who have studied international terrorism all agree that the war on terror and George W Bush’s mantra of ‘if you not with us, you’re against us’ was the worst possible mistake

The other point the documentary makes is that such outrages underscore the futility of trying to stop terrorism entirely. Oey says: “When we decided to make this series, we were having these attacks all over Europe. I felt the need to make something that showed that you can’t prevent terrorism.

“The Americans sometimes seem to think that you can prevent terrorism. We spoke to some FBI people who still think if they had had tighter security then 9/11 or the attack on the USS Cole might not have happened. I don’t believe that. If somebody wants to hurt you for terrorist reasons, it is going to happen anyway.”

An additional common error, Oey believes, is to see terrorists as one unified enemy. “People who have studied international terrorism all agree that the War on Terror and George W Bush’s mantra of ‘if you not with us, you’re against us’ was the worst possible mistake. It gave the worst possible people in countries like China and Russia the opportunity to say, ‘oh, these opponents are terrorists’.

“You have to look at terrorists from an individual perspective without making them part of an international movement. There is no real international Islamist movement.”

The producer goes on to give an example. “When an Australian researcher into terrorism was doing fieldwork in Bandung, Indonesia, he was stopped by this hostile group of people.

“He asked them where they were from, and they had to admit they were not from Indonesia. They were from Yemen. They had come from Yemen to Indonesia to fight the international jihad. So the researcher asked them, ‘but what does Yemen have to do with Bandung?’”

Terror also opens up an intriguing debate about how we define terrorism. In the documentary, Salah Shadio, a major general from the PLO, asks: “What’s the definition of terrorism and struggle? When the west does something, it’s struggle. When we do it, it’s terrorism.”

The standpoint from which you view terrorism is key, then. “Terrorism is something that needs to be looked at from many perspectives. If you do that, you might understand it better and tackle it better in the future,” says Oey.

What’s the definition of terrorism and struggle? When the west does something, it’s struggle. When we do it, it’s terrorism

These attacks could in some respects be regarded as what Oey calls, “a poor man’s version of warfare”. Marginalised people might feel this is their only way to be heard. “They are saying, ‘I have nothing. I don’t have guns. What can I do? I can blow up a car.’

“To remember that I think is really important. If you look at these acts from the perspective of someone who is poorer, and less powerful, and has fewer means, it really changes your view. All of a sudden you see this is someone who is less capable, who always feels like the underdog.”

We end as we began – with the astounding figure of Shaul Ladany. Would he describe himself as the ultimate survivor? Laughing, he replies: “I don’t know about that. What I can say is that in my life there has never been a dull moment.”

Succinct as always, he concludes: “I’m still alive. I can take on anyone.”

‘Terror’ is on PBS America at 7.35pm on Thursday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks