The mysterious death of Enrique ‘Kiki’ Camarena

Thirty-six years ago, the murder of a DEA agent began one of the biggest manhunts in North American history – and was an ominous warning of things to come. But was he killed by the cartel, or betrayed by his own people? Benjamin T Smith has spent a decade trying to find out

It was 7 March 1985 and the DEA’s chief Mexico agent, Ed Heath, was in the morgue again. He was staring at what remained of a heavyset Hispanic male. Since he first arrived in Mexico nearly 20 years earlier, Heath had got used to seeing what violence could do to a body. In the 1960s, he had adventured into the hills above Acapulco, and shot chunks out of peasant weed smugglers in sweaty, nerve-racking shootouts. When he returned in 1973, he had watched his friend, the Mexican police commander, Florentino Ventura’s savage interrogation techniques firsthand. He had even gone out for drinks with him afterwards.

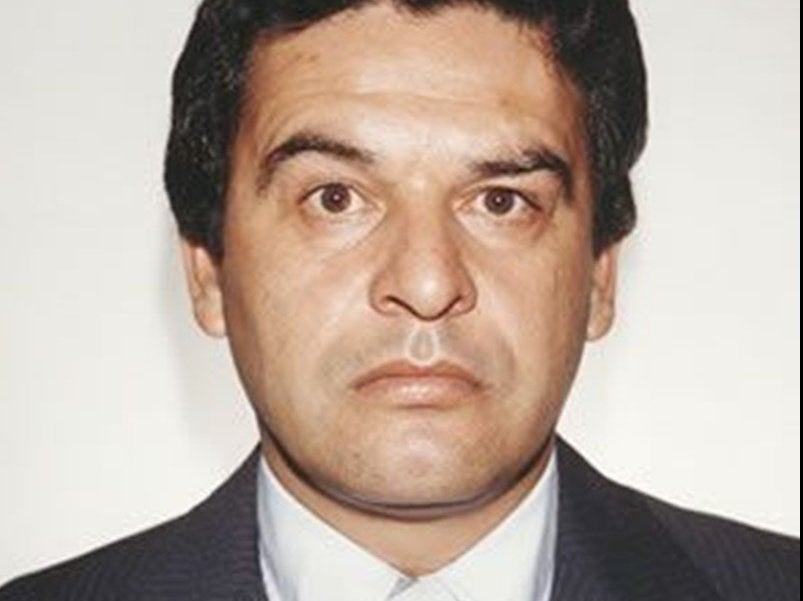

But this was different. At least it felt different. The body was that of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena. The dirt-flecked corpse was now in such a state of decay it was difficult to tell exactly how he had died. It was certainly a few weeks ago now. Three ribs were broken. So was his right arm. There were bruises, cuts and burns all over his body. And his rectum had been violated by a stick. But doctors reassured Heath that what finally killed Camarena was the deep indentation on the left side of his head.

The drug war was a numbers game. Its success or failure was measured out (and manipulated) by endless graphs of arrests made, kilos seized and purity affected. Heath knew this better than most. He was one of the few field agents to have risen through the ranks to become an administrator. And he had done it by encouraging DEA support for Mexico’s numbers-focused effort.

Yet, occasionally, the scale of the war narrowed. Budgets, policies and, in the final analysis, lives could be shaped by a single public scandal, unfortunate overdose, or grisly death. Such events had the power to drive panics and direct governments. As Heath stared at Camarena’s remains, it occurred to him that this was probably one of these moments.

Camarena’s murder was a turning point for the Mexican drug trade and the American war on drugs. Some of the effects, even then, Heath could have imagined. The subsequent investigations broke up the Guadalajara cartel and brought an end to the Mexican secret service – the Ministry of Federal Security, or DFS.

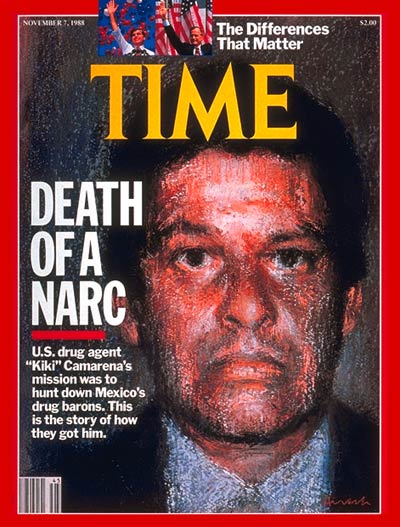

Back in the United States, Camarena became the drug war’s first martyr, the poster-boy for the DEA. His sacrifice bolstered the department’s budget, its personnel and its political standing. Money and plaudits finally brought what administrative overhauls could not. And it finally shook off its reputation for shoddy fieldwork, institutional racism, ruinous infighting and criminal collusion. By the late 1980s, it spearheaded America’s increasing focus on international counter-narcotics.

The empire had a new enemy. And the empire’s face was now a dead Mexican-American drug agent.

But over the years, Camarena’s story became much more than a prop for US drug hawks. As the investigations rolled on, a motley gang of difficult DEA agents, intrusive journalists and ageing academics started to poke around at the inconsistencies in the official case. They questioned the killers’ motives. They connected it to a rash of other suspicious murders. And they found a whistle-blower – a 6 foot 7 American spook called Lawrence Victor Harrison. He told another story, one of US corruption that involved the CIA and its plans to fund Nicaraguan paramilitaries with Mexican cocaine money.

And so what had begun as a simple morality tale has started to resemble the drug war’s JFK assassination. A solitary murder is now overlaid by so many myths and theories that gleaning the truth is not only extremely difficult but also kind of missing the point. What had happened to Camarena is now less a question of evidence and more a question of belief.

Despite these difficulties, over the last decade I have attempted to piece together the story of the murder and the subsequent investigation using dozens of interviews with DEA agents, Mexican cops and journalists, and mountains of classified DEA and Mexican documents. The story that I lay out here forms one chapter of my book, The Dope: Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade.

Around 2pm on 7 February 1985 four men bundled Camarena into the back of a car. They drove him from the US embassy to a quiet suburban house in the western district of Guadalajara. The same day they also seized a pilot, Alfredo Zavala Avelar, who had worked with Camarena on several weed cases and took him to the house. Here, secret agents and traffickers brutally beat and tortured the two men. They burned them with cigarettes, poured gunpowder into their wounds and set it on fire. They were questioned about everything, from the identity of DEA agents and confidential informants to what they knew about traffickers, policemen and politicians. Within two days they were dead or at least near it. Bodyguards put a tire iron through Camarena’s head to make sure, dumped them both in the back of a car, and then buried them at night in the Primavera Park west of the city.

Around three weeks later, federal cops instructed the killers to dig up the bodies and dump them on El Mareño ranch in the neighbouring state of Michoacán. They wanted to frame the trigger-happy congressman who lived on the farm or the corrupt cop who allegedly owned it. At the very least, it would confuse the investigation and put the gringos off the scent.

But years of complete impunity do not breed organisational discipline; and coordination was not their forte.

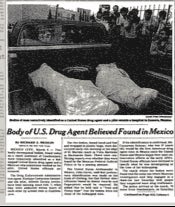

On 28 February a Mexican federal commander showed the DEA an anonymous note. It claimed the bodies were on the El Mareño ranch. It was one of many tip-offs that the office had received. But, for some reason, the federal cops took this one seriously. On 2 March they organised a raid on the ranch, were allegedly met by automatic gunfire, and killed all four inhabitants including the congressman. A full three days later they allowed the DEA agents to conduct a search of the place. The DEA found nothing.

The next day, however, a local farm worker spotted a couple of plastic fertiliser bags dumped by the side of the road outside the ranch. One was ripped and two discoloured legs jutted out. One of the traffickers later confessed that he had been ordered to dump the bodies, but had arrived too late. He saw the place was already surrounded by cops and so decided to dump them nearby.

This was how Ed Heath found himself in the morgue of Zamora Red Cross Hospital peering over Camarena’s month-dead corpse.

The Americans had lost agents in Mexico before. In 1969 they lost the head of the Mexico office in a mysterious drowning off the Acapulco coast. In 1974 traffickers shot two agents in bungled stings in a single year. And there were numerous tales of wild firefights, drunken bar brawls and near misses. But these were quickly covered up. They were embarrassing. They revealed that US officials were doing some pretty sketchy things, at best incompetently and at worst illegally.

This time it was different. The American government made it clear that they expected the Mexicans to find Camarena and his murderers. Their tactics were from the traditional drug war playbook – a mix of economic blackmail and public humiliation. In mid-February, customs officials organised a weeklong stop-and-search at the border. Next, the US ambassador gave a press conference in which he declared that Guadalajara was the centre of the Mexican drug trade. He also first floated the story that Camarena’s kidnap was probably revenge for a huge marijuana seizure at the Búfalo ranch in northern Mexico in late 1984.

Soon afterwards, the head of the DEA started to name names, going on primetime TV to accuse Mexican drug traffickers Miguel Angel Félix Gallardo, Rafael Caro Quintero, and Ernesto Fonseca of orchestrating the murder. He further claimed that Mexican police officials were protecting the traffickers and that they had even helped two of them escape overseas.

Such accusations were embarrassing and threatening. And they started to push the Mexican authorities to make arrests. In March 1985 they placed the DEA’s favorite Mexican cop, Florentino Ventura, in charge of the investigation. He moved to Guadalajara and rounded up trafficker bodyguards and associates. He used waterboarding and electrocution. And he started to innovate, partially cooking suspects’ feet in specially adapted microwave ovens. Some started to talk. Not coincidentally, they echoed the Americans’ accusations. They blamed the murder on revenge for the Búfalo ranch. And they pointed the finger at Caro Quintero, Fonseca, and their official backers.

The interrogations started a flurry of activity. On 4 April, Ventura arrested Caro Quintero at a beachside resort in Costa Rica. And three days later, his men seized Fonseca in Puerto Vallarta. The following day the Ministry of the Interior cancelled all the credentials of the Mexican spy service (the Ministry of Federal Security or DFS) and effectively closed the service down.

After this initial burst, progress slowed. US investigators met a mix of indifference, vested interests and a grindingly slow judicial system. But little by little, they took down many of those involved. In 1989 the Mexican authorities announced arrested Félix Gallardo and former DFS head (in June 1989). Both received heavy sentences. Whether they were involved in the murder or not, by the end of the decade, most of what the Americans now termed the Guadalajara cartel were either in prison or dead.

The arrests should have cleared up the matter once and for all. Yet in the years that followed, it had become clear to those investigating the killing that the DEA’s story was dubious. It was myth making as murder inquiry. They also discovered that other mysterious government agents moved in the same circles as the suspects. They were the CIA.

Over the past three decades, CIA involvement in Camarena’s death has gained considerable traction in Mexico. It culminated in a series of exposés in the immediate aftermath of Caro Quintero’s release in 2013. There was a frontpage in Mexico’s leading news magazine, a best-selling book, (J Jesús Esquivel’s La CIA, Camarena y Caro Quintero: La historia secreta), radio interviews and online followups. Ask most news-savvy Mexicans who killed Camarena and they will now repeat the journalist’s line: “It was the CIA.” And if they are really clued up, they will list another half dozen or so high-profile murders with CIA fingerprints.

In comparison, most Americans have resisted the idea. To stick, conspiracies need to be comforting and the CIA drugs-for-arms racket is neither. So the journalist who first broke the story was rubbished by the mainstream press and hounded to an early grave. The 2013 investigations were briefly covered – somewhat strangely – on Fox News. But they were almost immediately dropped. Fox invited on a delusional conspiracy nut to undermine the serious accusers. The Mexican journalistic exposé was never translated; an American version of the tale was quietly published online and quickly forgotten. And the whole dubious story of DEA heroics and Mexican corruption was restated for a contemporary audience in the Netflix series, Narcos: Mexico.

So beyond Camarena’s story, what do we know?

DEA and Mexican documents reveal that the original investigation into the Camarena case was deeply flawed. Inquiries were made at pace; crime scenes were systematically destroyed; and confessions were elicited by torture. Unsurprisingly these confessions followed exactly what the Americans wanted. As the ambassador had speculated a few days after his disappearance, the confessions claimed that his death was revenge for the Búfalo bust. It was a simple, comprehensible tale that made the DEA look good and the Mexicans look bad.

Yet the Búfalo revenge story is improbable. First off, Camarena had nothing to do with the Búfalo bust. The informant was an escaped ranch worker. He had approached the DEA’s office in Hermosillo not Guadalajara. And it was Hermosillo’s agents that approached the Mexican cops to coordinate the bust. Furthermore, according to one of Caro Quintero’s pilots, the police who raided the ranch returned most of the captured marijuana to the traffickers within weeks of confiscating it.

So, where now?

It was a question that the DEA agent, Hector Berrellez, had also started to ask himself. In 1989 the DEA put him in charge of running the Camarena case. Berrellez was a Vietnam vet with 15 years in the service. He had worked undercover in the US and Mexico. He knew traffickers and knew that they could be violent. But the Camarena killing didn’t add up. Why had an alliance of fabulously wealthy traffickers, right-wing thugs, and secret service officials opted to kill a DEA agent? Why had they risked their wealth, their freedom, and their families? For revenge? For a few million dollars of pot? That they probably got back?

Berrellez had heard rumours about the CIA’s involvement in the cocaine trade before. He had seen US cargo planes landing on a Mazatlán ranch. He had been told that they were bringing in guns for the CIA. And he had been ordered to stay away. “I’m a good soldier. It was a government operation, so I left it.” A Guadalajara DFS agent – that had fled to the United States –told Berrellez that his job had been to protect Mexican and Nicaraguan traffickers. They were moving drugs north and shipping weapons south. He said that they were working on the instructions of the CIA.

And in the year Berrellez took the Camarena case, the US Senate released the Kerry Committee Report. The report stated that the Nicaraguan Contras were funding their civil insurgency against the left-wing Sandinista government with cocaine money. They were in what the report politely termed a “symbiotic” relationship with drug traffickers. And the CIA knew all about it.

The CIA was, of course, keen to deny this. And it did so repeatedly. But over the next decade, the connection between the CIA and the Contras became increasingly transparent. CIA insiders, shady contract pilots, disillusioned DEA agents, and a handful of traffickers all testified that the company had sought to get round the US Congress ban on Contra funding by establishing a drugs-for-arms racket. Traffickers would bring drugs to CIA-protected airstrips in the United States. They would exchange cocaine for repurposed Vietnam-era assault rifles and cash. And they would return with their haul and split it between the Contras and the Colombian cocaine lords.

The question was what role the Guadalajara gang played in all this. The Guadalajara DFS agent suggested that if Berrellez really wanted to get to the bottom of it, he needed to bring in the traffickers’ radio specialist. He was nicknamed “White Tower”.

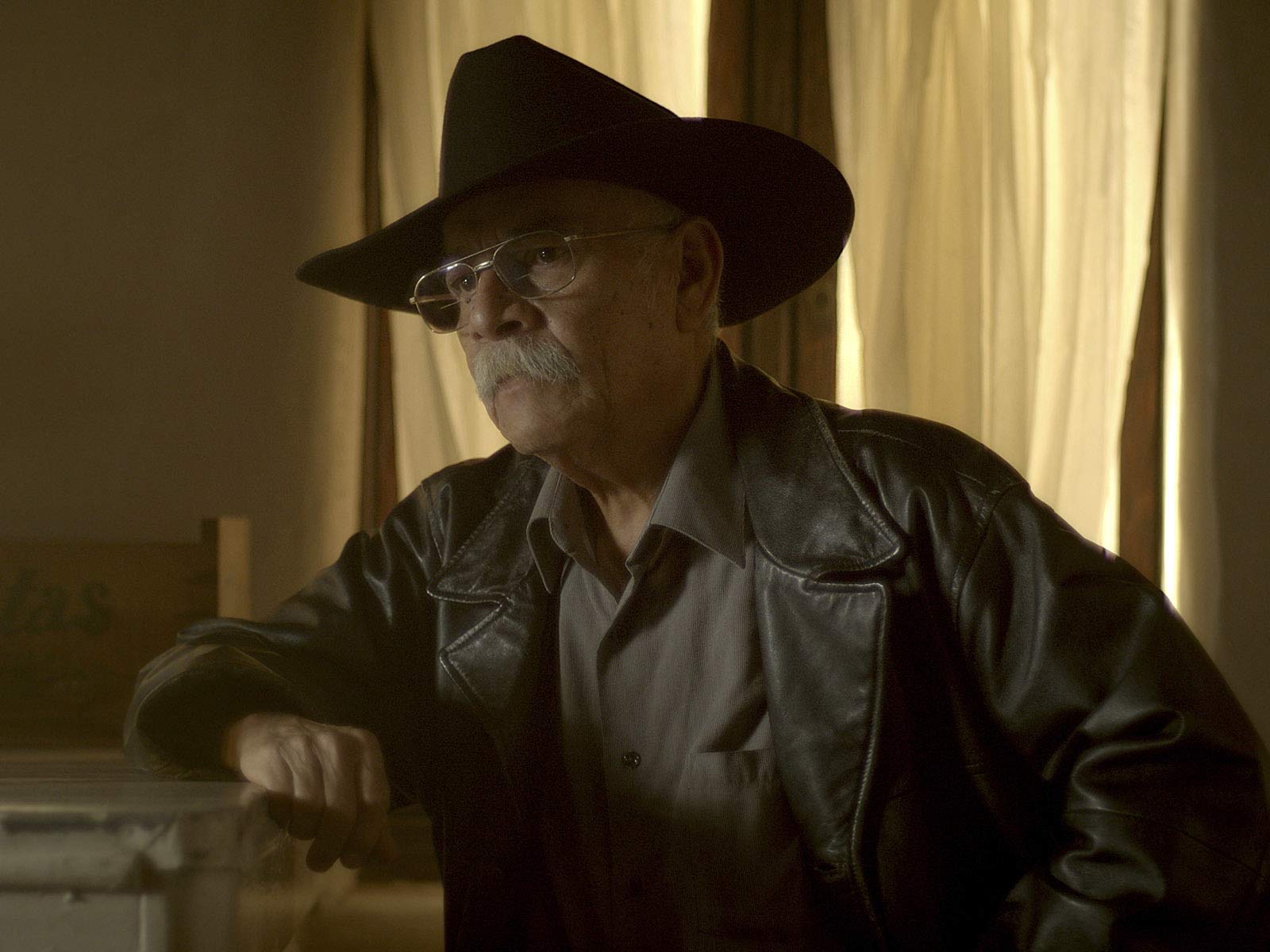

It was a fitting moniker. In a story full of mysterious characters, White Tower was the most enigmatic of all. He was not your average Guadalajara tough. For a start, he was a 6 foot 7 American. His real name was probably George Marshall Davis. However, there was considerable confusion. In 1990 the court transcriber misheard his name and took it down as George Marshall Leyvas. And throughout most of his time in Guadalajara he was known as Lawrence or Lorenzo or Larry Victor Harrison.

From what we now know, it seems that Davis was born in Pasadena in 1944. His father died when he was young and Davis grew up in 1950s California as a rebel but a smart one. Despite a brief stint in foster care and reputation for using his fists, he passed his high school certificate and in 1964 moved to San Francisco. It was the Swinging Sixties. But it was also the Cold War. And Davis – the rebel - took another direction. He became a conservative. He worked on Nixon’s failed presidential campaign; he sat in at classes at Berkeley’s law school; and he got close to oilman and diplomat George McGhee. It was probably McGhee who got Davis a job in the CIA. By the end of the decade Davis had changed his name to Lawrence Harrison, moved to Guadalajara, and was working with DFS agents tracking down left-wing insurgents.

Over the next decade he continued to work undercover for the company and the DFS. At the time, the two were tightly intertwined. They had the same enemies – foreign communist agents, Marxist students, and real or suspected guerillas. For the more paranoid of America’s Cold Warriors, Mexico was the buffer between an increasingly liberal United States and a mass of communist-sympathising, Cuba-inspired Latinos. Mexico had to be kept stable at all costs. So it was a close arrangement. DFS chiefs were CIA assets; and CIA agents worked out of DFS offices and carried DFS badges.

While undercover, Lawrence Harrison took on various jobs. He taught English to Guadalajara students, passed the names of those with guerrilla sympathies over to the DFS, and never saw them again. He moved briefly to Acapulco, got close to Mexico’s counter-insurgency specialist, General Chaparro Acosta, and saw the bodies of traffickers and guerillas wash up on the surrounding beaches. And he worked briefly as a legal advisor for Mexico’s governing party.

As the threat of left-wing insurgency diminished, Harrison’s role changed. By the early 1980s he had moved from law to tech. And he started to establish radio networks for DFS agents and their friends in the Guadalajara drug racket. It was in this job that he got close to one of the key Camarena suspects, Ernesto Fonseca. He even moved briefly into one of the drug lord’s lavish, suburban houses. But as the Mexican authorities picked up the rest of the cartel, Harrison was tired, scared, and increasingly distrustful. Loose ends were being tied up. Maybe he would be next? As a result, when Berrellez tracked him down, phoned him up and offered him protection in return for testimony, Harrison agreed. After two decades living undercover in Mexico, the lanky spook finally came home to the United States.

Until his death in November 2018, Harrison would only occasionally speak on the record. He was questioned by Berrellez at length; he testified at a handful of grand jury investigations; and he gave cryptic interviews to a few journalists and academics. Reading the transcripts, he was clearly a difficult interviewee. Sworn to secrecy and 20 years a spy, he was always careful what he said. He never, for example, directly admitted that he worked for the CIA, though it was pretty clear that he did. His patter was often convoluted and opaque. It was short on direct accusations and big on hints and inferences. It needed prior knowledge and begged for triangulation.

But, in essence, what Harrison claimed was as follows. Following Congress’s 1982 ban on funding the Contras, the CIA had sought to use cocaine money to buy them guns. Oliver North, a member of the White House’s National Security Council, led the effort. He was helped by the Cuban American covert ops specialist, Félix Rodríguez, who organised the day-to-day running of the operation. Together they worked with Central American cocaine smugglers who shipped the narcotics and the guns through Mexican airstrips. They also, Harrison claimed, started to train Contras on the traffickers’ ranches in the Caribbean state of Veracruz.

The system was not, however, foolproof. And the CIA and its Mexican allies constantly feared detection. Illegally running guns through Mexico was bad enough. Buying them with cocaine money as the crack epidemic took off risked setting America on fire.

So they dealt ruthlessly with possible discovery. In 1984, for example, a Veracruz journalist started to investigate rumours of the Americans running military training camps in the state. He passed on the rumours to the well-connected and combative Mexico City journalist, Manuel Buendía. Almost immediately afterwards gunmen shot Buendía and the Veracruz journalist dead. In a none-too-subtle hint they sowed the Veracruz journalist’s lips shut with wire. And when the DEA agent, Kiki Camarena, started to investigate the conspiracy a few months later, the CIA used its allies in the Mexican drug world to do the same. After kidnapping him, questioning him about what he knew and who he had told, they killed him.

Many – including some members of the DEA - have dismissed Harrison as a crank. But those who personally met him, from Berrellez to the veteran border journalists Charles Bowden and Molly Molloy, to two rather dry Wisconsin academics were convinced by his story. Berrellez even sent him for a lie detector test, which he passed on three separate occasions.

And a lot of his story rings true. It indicates why traffickers like Fonseca and Caro Quintero seemed so confident of their own impunity. They were not only being protected by the CIA; they were doing its bidding; they were fighting the Cold War. It chimes with the confessions of other US operatives involved in the drugs-for-guns scandal. It explains why someone recorded tapes of Camarena’s interrogation; it explains how the CIA managed to get hold of these tapes a few weeks after the murder; and it suggests why one of the tapes ends with Camarena’s interrogators asking him about a ranch in Veracruz.

But there are also holes. Big holes. And because it is about the CIA, there are conspiracies. And there are conspiracies within conspiracies. They are enough to fill another book. (In fact, if readers are interested there is an exhaustive and rather paranoid study by the two Wisconsin academics).

The first concerns the supposed Contra training camps in Veracruz. Despite repeated reference to these, no one has any idea where they were. Instead there are multiple, unproven theories. Some claim that they were in northern Veracruz on the ranch of the ageing hit man and heroin trafficker Arturo Izquierdo Ebrard. Others claim that they were established somewhere in southern Veracruz near the location of a poorly explained massacre of federal cops (but the locals I spoke to maintain that Mexican weed smugglers killed the cops and deny any knowledge of covert military camps). And the only published mention the dead Veracruz journalist made of CIA-run sites was not even in Veracruz. It was in the Sierra Negra in the neighbouring state of Puebla.

The second concerns the DEA investigation. In the two years following Berrellez’s encounter with Harrison, the agent managed to secure more witnesses to the Camarena murder. Their evidence helped put away half a dozen other alleged culprits Some of the witnesses’ statements rang true and backed up Harrison’s claims. (They claimed, for example, that they had seen the Cuban American covert ops specialist Félix Rodríguez visit the traffickers. He had used the pseudonym Max Gomez.)

But there were problems. Despite coming from unschooled memories, the witness statements were disturbingly consistent. They named the same names; they focused in on the same incidents. Furthermore, they alleged the direct and open collusion not only of CIA operatives, but also high-up Mexican government officials. They claimed – incredibly – that these officials, including the secretary of defense and the secretary of the interior, openly planned the Camarena killing and visited the house while he was being tortured to death. Such accusations not only undermined their statements, they called the whole investigation into question.

The third issue concerns the role of Camarena’s DEA colleagues in Guadalajara. In Esquivel’s 2013 exposé, one of Berrellez’s witnesses claimed that he recognised one of Camarena’s DEA colleagues at one of the trials. The colleague was there to give a character statement for one of the defendants. The witness went on to say that he had seen the colleague before. At the time he hadn’t known he was DEA. But he had seen him receiving money from the Guadalajara traffickers. He now presumed it was payment for protection. It is a claim that has refused to go away. Over the last few years more former cops have backed it up and offered some salacious (and unrepeatable) details. It is also a claim that may explain why on the tapes Camarena’s interrogators repeatedly asked him about the money traffickers were paying him. (It is something you can read Camarena repeatedly deny).

Did – as some now speculate – one of Camarena’s DEA colleagues take a bribe, claim that he had passed it onto Camarena, and then blame Camarena when the traffickers’ fields were raided and their bank deposits seized? Was the DEA as involved in Camarena’s death as the CIA?

As any reader that has followed these claims and counter-claims up to here may be starting to realise, the Camarena case is still a deep, dark hole. And it is one that is still getting deeper. The DEA investigation continues to this day; it is now 35 years old and counting. Fiction and reality are firmly intertwined. In 2019 they recruited another alleged witness; series two of Narcos: Mexico was released; and USA Today hinted at new prosecutions. In 2020, Amazon Prime’s documentary on the investigation, The Last Narc, was announced, delayed and then released. It was cut for legal reasons. But the DEA agent accused on collusion in the documentary is still in the process of suing the show for defamation.

Read More:

Parsing all the evidence, reading through all the testimonies, and comparing them to similar accusations of CIA-backed drug running in southeast Asia, Afghanistan, Central and South America, it seems likely that US agents were using the Guadalajara traffickers to move cocaine and guns. The stories of training camps are unproven but plausible. Secret services – working with no oversight and complete impunity - have always gravitated towards money and resources. And I would be extremely surprised if some of the DEA agents in Mexico were not on the take. They had been in the past. And they would be again.

What we do know is that what started off as a rather simple tale of perseverance and sacrifice has become a vortex. It sucks in all the drug war’s murderous grievances, political feuds, and hypocrisies. It has come to embody the blurred lines separating myth-making, counter-insurgency, drug trafficking, and policing. What you think about the Camarena case now doesn’t reflect what happened to the murdered DEA agent. It signals what you think about the drug war. It signals what you think about Mexico and the United States.

‘THE DOPE: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade’ (Ebury Press, £20) by Benjamin T Smith is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments