The American woman who made free school meals part of the fabric of British society

A century before Marcus Rashford took on the government over free school meals, one of the fiercest social reformers in history was starting the fight. David Barnett remembers Margaret McMillan

Free school meals are one of the cornerstones of our welfare state – and, in recent weeks, a contentious one at that, as it fell to 23-year-old Manchester United forward Marcus Rashford to take on the government and eventually force a U-turn over the provision of free school meals during the holidays, to offset the money problems affecting families during the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s a little over a century ago that the idea of free school meals became part of the fabric of British society, and that was only after years of work in Bradford, West Yorkshire, led by – and this is possibly the surprising bit – an American.

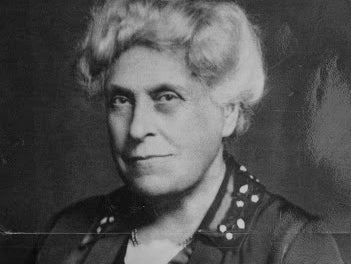

The name of Margaret McMillan is one that is honoured in Bradford as much as those of JB Priestley and David Hockney. There is a Margaret McMillan Tower, which houses the city’s local studies library and other council offices, and a nursery school and primary school named after her.

Unlike those famous sons of Bradford, though, McMillan was not from the city. She was born in Westchester County, New York, in 1860. But her work would have nothing less than a revolutionary effect on first Bradford, and then the rest of the country.

Lauren Padgett, of Bradford Council’s museums department, curated an online exhibition looking at Bradford’s education pioneers earlier this year, and she offers this succinct biography of McMillan: “Born in America in 1860 before her family moved to Scotland, McMillan and her sister Rachel became involved with political and social campaigns in London. They moved to Bradford in 1892 to help improve the health and education of Bradford’s poor children.

“In 1892, McMillan and Dr James Kerr, the local school medical officer, conducted one of the first school medical inspections in Britain. Based on their findings, McMillan argued that local authorities should provide schools with bathrooms and good ventilation, and free school meals to improve the health of sick, poor and hungry schoolchildren.

“She joined the Bradford school board in 1894, introduced a school medical inspection scheme in 1899 and a free school meal scheme in 1904, one of the first in the country. Her campaigning for compulsory free school meals brought about the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act and the 1944 National School Meals Policy. She remained committed to improving children’s education and health until she died in 1931.”

McMillan’s parents Jean and James had originally emigrated from Inverness in 1840, and it was after the death of James in 1865 that Jean took the girls back to Scotland. McMillan studied psychology and physiology, then went to Germany to study languages and music. While there she was introduced to the idea of Christian socialism, and in 1888 returned to London to join her sister Rachel where the pair became highly politicised.

They met with the textile designer William Morris and the Russian anarchist and revolutionary Pyotr Kropotkin, and in 1889 became involved with the London dock strike.

In 1892 it was suggested to the sisters that their dynamism and work would be of value in Bradford, then an industrial powerhouse of textile production but with some of the worst poverty in the country.

At around the same time, an organisation was being formed in Bradford that would also have national repercussions. It was called the Bradford Cinderella Club, and its aims were to help underprivileged children living in such woeful deprivation in the city. Crucially, the Cinderella Club was fiercely independent of political influence, and politicians and the church were deliberately and strictly excluded from participation.

Their biggest early project was working with families affected by the Manningham Mills strike of 1891, and their work was so well-received that it caused organisations such as the very active Labour Church – a religious organisation for the labour movement – to respectfully back off. A report in the city’s clarion newspaper observed: “The Cinderella work is so well developed and organised that it covers the whole area of the town, it would only be productive of mischief for the Labour Church to interfere in it.”

The Cinderella Club endeavoured to provide a free meal to every underprivileged child during winter, and at one point was handing out 40,000 food parcels a year. It was this work that caught the eye of the McMillan sisters, and Margaret convinced Dr Kerr that something had to be done about the problem.

Margaret McMillan was a pioneer in so many respects and campaigned for universal suffrage … Although Margaret was from New York, it goes to show that it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can still be a great Bradfordian

McMillan later wrote: “The condition of the poorer children was worse than anything that was described or painted. It was a thing that this generation is glad to forget. The neglect of infants, the utter neglect of toddlers and older children, the blight of early labour, all combined to make of a once vigorous people a race of undergrown and spoiled adolescents, and just as people looked on at the torture of 200 years ago and less, without any great indignation, so in the 1890s people saw the misery of poor children without perturbation.”

McMillan got the Labour MP Fred Jowett onside and together they started an experiment of providing free school meals at Green Lane School, which, incredibly, was actually against the law at the time – they could have been prosecuted for feeding hungry children.

After their experiment McMillan and Jowett went to parliament to persuade them to introduce legislation that would not only stop it being illegal to provide free school meals, but to actively encourage all local authorities to do so. She argued that if the state was going to force children to go to school, it was also the state’s responsibility to feed them.

Their case was supported by studies and work going on elsewhere in the country, including a report published in 1889 that said more than 50,000 school children in London were “in want of food”, as well as Charles Booth’s treatise Life And Labour of the People of London, and Seebohm Rowntree’s 1901 study of poverty in York.

It took many years of campaigning because – and here we find some synergy with Rashford’s recent campaign that has eventually forced Boris Johnson to U-turn on free school meals during holiday time – the government was simply not willing to spend the money. When a bill was eventually drafted and discussed, the House of Lords objected strenuously to the idea. But in December 1906, the Education (Provision of Meals) Act was finally passed, and free school meals became enshrined in British law.

The Cinderella Club that had been formed in Bradford and which inspired McMillan to act became a national network of organisations dedicated to ending child poverty. Over the decades, the clubs became defunct, except in the place where they started – Bradford. The Cinderella Club is still an active force for good in the city today.

And Margaret McMillan is still a huge presence in Bradford as well. She has a blue plaque on 49 Hanover Street, where she lived between 1893 and 1902. Writing for Bradford Civic Society’s guide to local blue plaque sites, Ben Hoole, manager of the Exchange bar in the city, said: “Much is written about our industrial heritage and remnants of these heady days are still visible across the city skyline.

“The lives of those working in the mills and living in the slums is largely forgotten, the homes torn down and memories fading. Margaret, through her research and years of hard work, had the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act approved in the House of Commons. Hungry children cannot learn, of course, and so they would be provided with school dinners.

“Margaret McMillan was a pioneer in so many respects and campaigned for universal suffrage. Her ideology and her passion for others resonates with the socialist within me. Although Margaret was from New York, it goes to show that it doesn’t matter where you come from, you can still be a great Bradfordian.”

And at the primary school that bears her name, Margaret McMillan is not just a forgotten figure from the past. She is a constant reminder to the children that pass through its classrooms that their school dinners are there because of her. In the dining hall, a large portrait of McMillan looks down on the children enjoying the fruits of her work 120 years ago.

Lorraine Martin, head of Margaret McMillan primary school, says: “We also have a big display of work by the children illustrating the status of Margaret in our school. She is a big part of our curriculum and our children are very proud that she started this important work here in Bradford.

“She has a very strong legacy in this area and it wasn’t just through her school meals work, she was very productive in many social causes.

“Obviously, though, the idea of proper nutrition is very important, and the story of Margaret helps the children to understand that. It’s especially important here in Bradford where there are high levels of deprivation and childhood obesity.”

Martin adds that it is also vital for children to have heroes of the kind of Margaret McMillan – and her modern-day counterpart Marcus Rashford. “I think that’s really important for schoolchildren,” she says. “Our motto is Inspiration, Aspiration, Determination, and that is based on the work and ethos of Margaret McMillan. Her life and work helps us to teach the children that they can aspire to stand up for what they believe is right, and to work to make life better for everyone.”

It would be nice to think that the work of Margaret McMillan is something that the pupils at the school named after her learn about as part of history. But, as we have seen in recent weeks, children going hungry has not been left in the past. And we have lessons to learn from McMillan and many others, according to Professor Sir Harry Burns, president of the BMA and former chief medical officer for Scotland.

Professor Burns says: “We recently saw days of vehement criticism of Boris Johnson after he refused to extend free school meals in England for the half term and over Christmas. While he praised the work of Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford, he refused to commit more money for meals, arguing that he had already given councils a £63m fund that could have been used towards this. The councils said this was already being spent on other Covid necessities.

“Leaving aside the political noise, the basic reality is that our poorest children are going hungry. This is not something that has been consigned to the narrative of Victorian social history. It’s happening today and without learning from history, we are doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past.”

According to Professor Burns, the 18th-century cleric Joseph Townsend said: “Hunger will tame the fiercest animals. It is only hunger which can spur and goad the poor on to labour.” Shocking, but if he was alive today, he would probably feel at home in the Department for Work and Pensions, an organisation that thinks it’s appropriate to punish the poor for being late for appointments by denying them benefits and allowing their children to starve.

He contrasts Townsend's view of the poor with that of Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest working in 1990s Los Angeles torn apart by gang violence, which saw many young people jailed. Professor Burns said: “Boyle argued that ‘gang violence is about a lethal absence of hope’. He started Homeboy Industries which created jobs for the community resulting in life-transforming changes for thousands of families and dramatically reducing community violence. He was asked to speak to the Violence Reduction Unit of Police Scotland in Glasgow. In expressing a view, somewhat at odds with Townsend’s approach to the poor, he told his audience, ‘What we need is a compassion that stands in awe at the burdens the poor have to carry rather than one that stands in judgement at the way they carry them’. He had learnt the lesson of history – lack of hope breeds despair and social breakdown.”

Thus, says Professor Burns, who gave up a 15-year career in surgery to study public health in his hometown of Glasgow, we have lessons to learn from both the far past and recent history when it comes to the effect of poverty on young people.

He says: “The recent decision by the government to vote against holiday meal vouchers in England certainly puts them firmly in Townsend’s camp. In addition to showing a lack of compassion, their actions show a scandalous lack of insight in child development. We know that adverse childhood experiences like neglect, domestic violence or parental mental illness affects child brain development. The Conservative view that people are poor because of the decisions they make might be reasonable if we lived in an equitable society – but we don’t. Quite simply, the circumstances into which children are born and raised determines their choices and, largely, their ability to make positive decisions and control their own lives.

“It clearly makes not just social but economic sense to provide free school meals. Poorer children who are hungry, are also likely to suffer other deprivations. This takes me back to Boyle’s ‘lethal absence of hope’. Our compassion for them, as human beings, is laudable, but, if we don’t address the wider social issues, we are hot housing a host of expensive social problems that society will have to pick up later.

“Providing school meals, particularly at a time of pandemic, makes both humanitarian and practical sense. Doesn’t our history moving from Victorian paternalism to the benefits of welfare state, including the founding of the NHS, with the huge improvements to the nation’s health prove this?

“During the pandemic, we will need more than ever to ensure that poorer are, at least, fed.”

It’s fair to speculate that Margaret McMillan, having left Bradford with the provision of school meals nationally under her belt, probably thought that a century hence things would be immeasurably better, not sparking the same debates.

After her work in Bradford, McMillan left with her sister Rachel to go back to London, and in 1908 they opened the country’s first ever school clinic at Bow, which was followed in 1910 by one in Deptford.

She published a book about her work and experiences in 1911, titled The Child and the State, where she passionately argued that school should not be just about preparing poor children for monotonous, unskilled jobs, but should rather offer a broad and humane education.

McMillan continued to be an activist in many areas of social reform, and was injured while protesting with suffragettes. She opened a nursery and training school for children aged between 18 months and seven years in Deptford in 1914, which was named after Rachel when she died three years later.

In 1922 she met the Austrian reformer and educationalist Rudolf Steiner, who referred to her as an “educational genius”. She continued to work for the benefit of children and against social injustice until her death in Harrow in 1931.

Born in New York, raised in Scotland, educated in Germany and died in London, after a lifetime of social campaigning. But McMillan’s work in Bradford is perhaps her most important, and work that has resonances today as the same arguments about feeding children raise their heads long after McMillan thought she had slain that particular dragon.

As the Christmas holidays approach and Marcus Rashford’s successful campaign feeds hungry children, the young footballer should feel comforted that the spirit of one of the fiercest social reformers in recent history has his back.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks