Murdering Marcia: Harold Wilson and the plot to kill his secretary

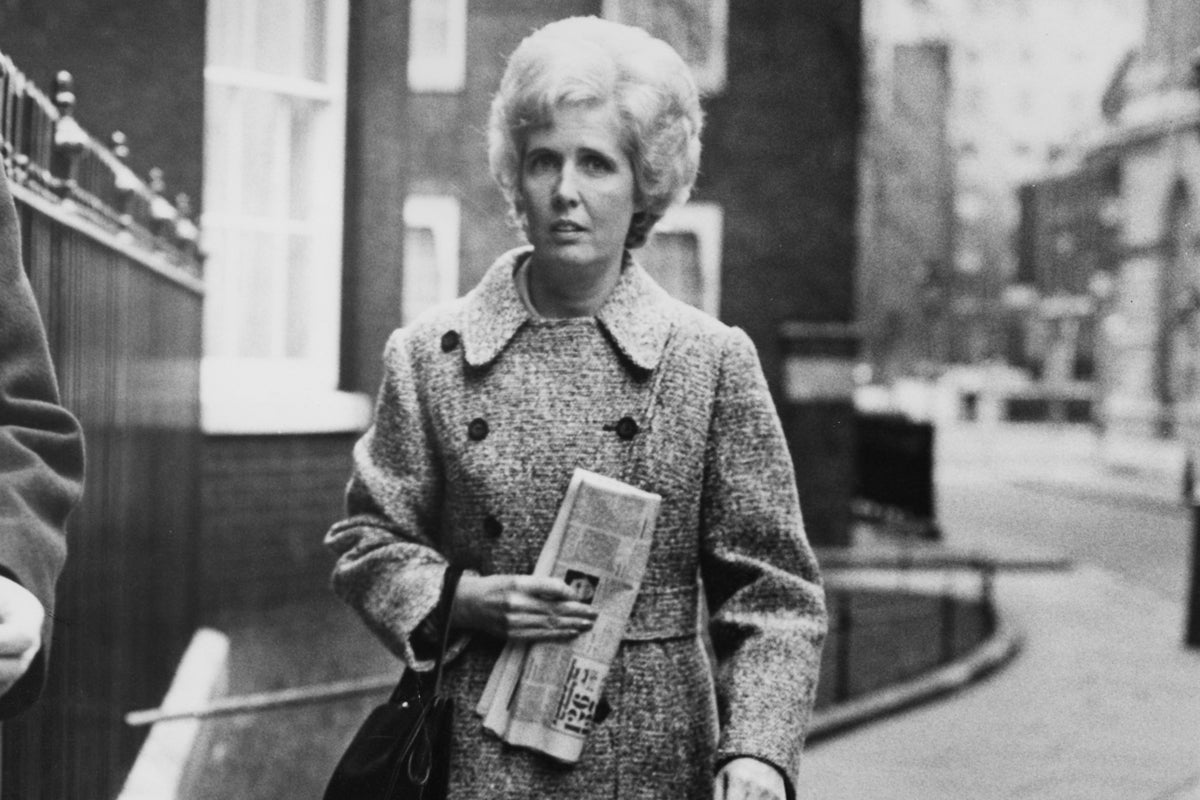

Formidable and controversial, Marcia Williams held the ear of Harold Wilson and made sure the Labour Party didn’t break at the seams. So why did three men plot to kill her? Sean Smith investigates

In the spring of 1975, three Downing Street officials wandered across the main square in Bonn, mulling over a plan to murder the British prime minister’s closest friend and confidante, Marcia Williams. Harold Wilson’s formidable and controversial secretary had helped him dominate British politics for 20 years. To the consternation of his critics, Wilson had ennobled her as Baroness Falkender the previous year but now the distinguished trio saw her as a toxic liability who threatened to destroy his health, premiership and legacy.

Ever since Wilson’s recently hushed up heart scare, his personal physician and concerned friend Joseph Stone, had become obsessed by a disturbing notion: murdering Marcia might just be “in the national interest”. Dr Stone was flanked by Joe Haines, Wilson’s bruiser of a press secretary, and Bernard Donoughue, the head of the Downing Street policy unit. When Stone had first sounded them out by suggesting “it may be desirable to dispose of her. We’ve got to get this woman off his back,” and, “Perhaps, we should put her down,” he had been deadly serious.

In Bonn, Stone again outlined how he could safely dispense with Marcia without arousing suspicion. As Lady Falkender’s doctor, he proposed to slip her a lethal quantity of her prescribed tranquilliser and then write up the death certificate as an accidental overdose. In Dr Stone, the trio may have had the means and opportunity of ridding Wilson of this “bothersome” woman, but it’s only by tracing the couple’s emotional co-dependency back over two decades that you can begin to understand the motive.

Read More:

Although she had a history degree from UCL, Marcia Williams was realistic enough to realise that the only way for an ambitious young woman from the provinces to land her dream job in national politics was to brush up on her secretarial skills. It was while working in the typing pool at the headquarters of the Transport and General Workers Union in 1956 that she became aware of an NEC plot to sideline Labour Party’s “coming man”, Harold Wilson. At that time, he was the brilliant shadow chancellor who was still seen as the standard bearer of the Bevanite strain of socialism that she so admired.

Williams was part of a group who risked their jobs by trying to warn Wilson. When she landed the job as his full-time secretary in 1956, colleagues were struck by their easy intimacy; they even finished each other’s sentences. Some felt that Wilson’s emotional dependency on Williams intensified after his mother succumbed to cancer in 1957.

From the start, it was clear that both shared an addiction to politics and its attendant circus of gossip and conspiracy. Marcia would always be his early warning system ever vigilant for ambushes and bear traps. She is credited with honing his political antennae into a survival kit of Wilsonian aphorisms like “Never enter a room unless you know where the exit is.” Colleagues were unnerved by her over familiarity with Wilson when she would chastise him as a “silly little boy”. Their intimacy fuelled the widely held belief that at some point there had surely been a sexual dimension to their relationship. According to legend, Marcia, exasperated by the constant speculation, had imperiously summoned Harold’s wife one day to settle the matter once and for all. “I have only one thing to say to you. I went to bed with your husband six times in 1956 and it was not satisfactory.”

But the role seemed to hold little prospect of affecting real change and she was considering leaving politics to train as a barrister when in 1963 the sudden and unexpected death of the labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, changed everything.

Williams’ advice was seen as key in helping Wilson see off the challenge of rival Jim Callaghan by shoring up support from the left to become first leader of the party and then the youngest prime minister of the century when he won the 1964 general election by the slenderest of margins.

Harold derived from her a particular kind of stimulus. She pierced his complacency on many occasions. She disturbed him, made him see things in a different way, more than anybody else I can recall

Marcia Williams was Harold Wilson’s formidable private and political secretary throughout his four terms in Downing Street and her job description was simple: protect Harold and help him hold the febrile Labour party together while he ran the country.

Wilson preferred to do his paper work at the cabinet table so he could be in close proximity to Marcia’s outer office where she would hold “kitchen cabinets” with friends and trusted colleagues. Anyone trying to secure much coveted facetime with Wilson was politely reminded to “fix it up with Marcia” first.

And from the start, she was an intimidating presence not afraid to raise her voice to call out perceived disloyalty. Within a month of taking office, she declared war on the civil servants who retained an obvious affection for Downing Street’s previous Conservative incumbents. She targeted the prime minister’s principal private secretary, Derek Mitchell.

Although it stopped short of the civil service “purge” Williams wanted, Downing Street staff were “restructured” and she had marked her territory. Mitchell postponed his removal temporarily by learning that you had to go along with Marcia to get along: “You couldn’t beat her, you had to join her, because the prime minister trusted her advice implicitly.”

Wilson confided in Mitchell: “She has stuck by me through thick and thin if I get thrown out, she’s still going to be my most loyal supporter.”

The press were to dub her “The Duchess of Downing Street” but internally staff nicknamed her the “Princess of Pettiness” because she picked fights over trivial matters. But the rows she carefully cultivated and evidently enjoyed were proxy skirmishes to secure the higher ground she needed from which to assert the prime minister’s authority.

Peter Shore was a junior secretary of state for economic affairs and keen student of their relationship in Downing Street and believed that whatever had passed before, their intimacy was now psychic and emotional.

“Harold derived from her a particular kind of stimulus. She pierced his complacency on many occasions. She disturbed him, made him see things in a different way, more than anybody else I can recall.”

Historians tend to characterise Wilson as a master tactician rather than a strategist because he prioritised party unity over the national interest, ducking and diving to keep the left and right wings of his party together. It’s a valid criticism which explains why the Wilson’s first administration from 1964-70 is widely seen as one which over-promised and underdelivered. But Wilson and Williams believed in party unity at all costs because they saw the Labour movement in its broadest sense as a force for good; as its custodians, they had to stop it coming apart at its left and right-wing seams.

Marcia Williams undoubtedly contributed to that success. It’s striking that Roy Jenkins “admired her judgement” from the right and Tony Benn enthused from the left: “Marcia is the best thing about the court at No 10.”

Electoral success was a vindication of their pragmatism. In a country where the electorate seems instinctively drawn to Conservatism, the wily Wilson managed to reverse that trend by narrowly winning four of the five general elections he contested. He occupied 10 Downing Street from October 1964 to June 1970 and from March 1974 until April 1976.

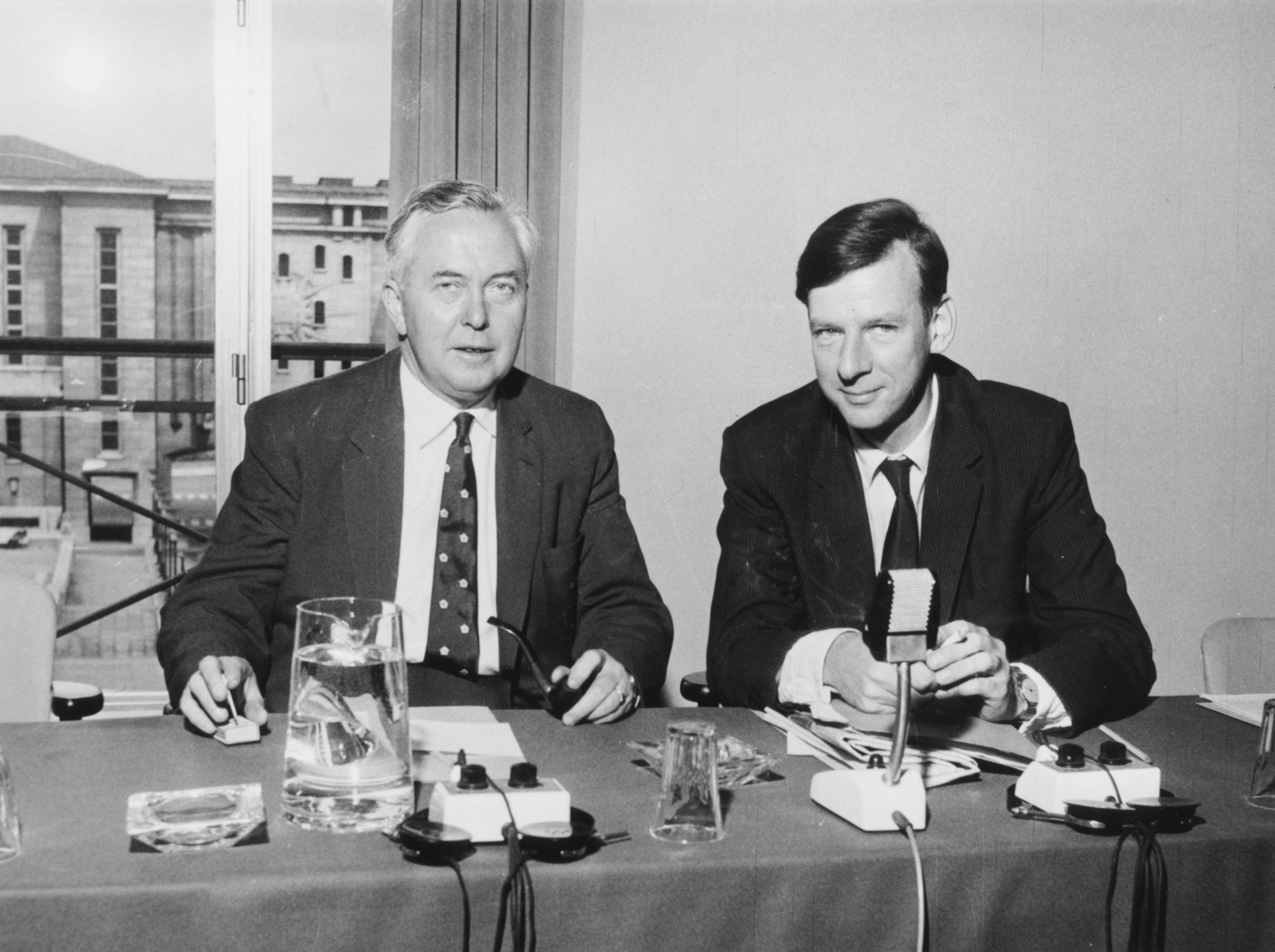

But from the start of Wilson’s turbulent minority government in 1974 there were problems. Wilson’s press secretary, Joe Haines was soon locked into a cold war with Marcia Williams with both vying for day to day control of Downing Street. Haines felt he was winning the hearts and minds of the “junior officers” to little avail because after nearly 20 years of emotional intimacy, the mercurial Marcia still had the ear of the “General”. And by 1974, besieged by economic crisis, rampant inflation and the prospect of civil unrest, Britain was derided as the “sick man of Europe” and Wilson was soon accused of losing control of the battlefield.

Marcia had been badly wounded by the so-called “land deals affair” as early as March 1974 where a series of unwise property investments by her family were seized on by the press as evidence of corruption.

Even Haines sympathised when the press besieged the Marble Arch home she shared with her young children. He estimated that in one week, over 6,000 column inches were devoted to the story, even though subsequently Marcia was able to demonstrate she had done very little wrong.

When political aides become “the story” it usually proves fatal but Marcia survived because of Wilson’s stout defence. When she returned to Downing Street she felt that that her position had been weakened and she clearly felt threatened by the Donoughue–Haines axis that was now running Downing Street. She did not take it well: Haines’ memoir opined that “the machinations and tantrums of Marcia Williams plagued our lives.”

But Wilson was still very much in thrall to Marcia. In a gloriously arrogant two-fingered salute to his critics and as an extraordinary gesture of loyalty to his embattled friend, he elevated Marcia to the House of Lords, by ennobling her as Baroness Falkender in July 1974.

Or alternatively, according to Haines, Wilson had been intimidated by Marcia’s veiled threats to reveal his darkest secrets. Much of Marcia’s legend has been crafted by Joe Haines’ series of increasingly incendiary memoirs based on his time in Downing Street. That day in Bonn, he may have saved Marcia’s life by telling Joseph Stone to stand down his plan to kill her, but as an author Haines has been “putting her down” in print for decades through relentless character assassination.

Haines relates contentious events through the prism of his own experience. When he refers to Marcia, his tone borders on the obsessive. He seems very much part of that generation who could only cope with intelligent, forceful women in the workplace by trivialising them. Although Haines claimed not to dislike Marcia, he caricatures her as a cross between Malcolm Tucker and Lady Bracknell.

When his generation’s tacit misogyny slips into plain sight he seems an especially unreliable narrator: “She should have been a ridiculous figure, consoled by a ‘there, there’, a pat on the knee before that constituted sexual assault.” Had Haines tried that, you suspect she might have broken his arm. Haines’ objectivity does seem compromised by a perfectly rational fear for his own safety. She had “charm which could captivate a stranger and a glare which could reduce an enemy to a shivering wreck.”

It was Haines’ account of the now notorious “Lavender List” that implicated Marcia in the “cash for peerages” scandal that surrounded Wilson’s resignation honours list in 1976 even though no evidence of financial impropriety was ever established. Baroness Falkender successfully sued the BBC for libel when they dramatised his version of events in 2007.

When Haines’ first sensationalised memoir first hit the stands in 1977, Wilson denounced it from retirement as a betrayal from a former friend. Wilson’s loyalty to Lady Falkender never wavered arguing that she’d always been a victim of endemic chauvinism.

Read More:

She agreed with imperious disdain that that Haines “liked neither women nor university graduates: I was both – a double offence”.

Lady Falkender’s own account is non-sensationalised, steadfastly loyal to Wilson but damning of her supposedly socialist colleagues who acted as if meritocracy was just for men: “Many leading Labour figures have an attitude to women’s rights completely opposed to the whole spirit of a movement that believes expressly in equal opportunity.” Only her beloved Harold was exempt.

But you only truly sense what she’d always been up against when she relates the labour leadership’s hoots of derision that greeted Mrs Thatcher’s toppling of Ted Heath to become leader of the opposition. “They were all laughing, joking,” wondering how “the Tories could possibly win with a woman at the head.” As the boys’ club chuckled at their own impending extinction, Lady Falkender seethed but she could at least rest secure in the knowledge that she’d done everything she could to warn them even though it later transpired they’d once considered killing the messenger.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks