The link between loot boxes, gaming, and childhood gambling

One problem gambler takes their own life every day, and there are 55,000 problem gamblers aged 11-16 in the UK. Sean Russell on the video games that encourage addictions and a gaming industry that remains defensive

At the age of 13, Jonathan Peniket begged his father to allow him to spend his pocket money on Fifa. He wanted to buy “packs” for his team, a random selection of players which he could trade, or use to play online. His dad said no, that it was gambling. But eventually Jonathan got his way. He didn’t regard it as gambling. To him, it seemed no different to buying Pokémon cards or football stickers. It was only when he’d spent more than £3,000 at the age of 18 that he realised the insidious nature of loot boxes.

Jonathan was first introduced to video games when he was a child. His older brother had a GameBoy and Jonathan would watch over his shoulder and occasionally have a go. Then one Christmas, when Jonathan was about eight, the pair were bought a PlayStation 2 as a shared present. It wasn’t much longer before Jonathan bought a second-hand edition of Fifa 2005.

Gaming became part of his life and, while he didn’t consider it a problem, several times his parents were worried he had become addicted. But what Jonathan was becoming addicted to was perhaps more harmful. When Fifa first introduced its Ultimate Team mode in 2009, it swiftly became a topic of conversation with all his school friends. The conversation turned away from who beat who 4-0 online last night, and instead became about who had which players in their teams, and who had the better virtual cards.

When he was 13, Jonathan reached a point in the game where he felt stuck. He wanted a better team but could not get it using the in-game points; instead he had to use real-world money to elevate the quality of the team to be competitive. He convinced his father to let him spend his pocket money on Fifa. Eventually his father caved and Jonathan bought his first loot boxes.

“At the start it was about getting good players,” he said. “Eventually it’s just about the buzz or chance of it all. Even if opening the box was slightly disappointing, it gave you the sense that ‘OK, I was unlucky there, if I just spend a bit more money, if I just put another £15 on the game, then I’d get lucky’. You always thought that you were close to winning.”

According to the House of Lords’ Gambling Harm report, released earlier this year, a young person who spends money on loot boxes is 10 times more likely to become a problem gambler than those who do not. Therefore, understanding the scale and dynamics of loot boxes, and other aspects of video games has become paramount. According to the report, on average one problem gambler takes their own life every day. There are already 55,000 problem gamblers aged 11-16 and that number does not include the children unaware that they have a problem; or those who may have an addiction to loot boxes or other gambling-like mechanics.

A loot box is a virtual item which can be redeemed to receive a randomised selection of further virtual items. It’s a game of chance: you hand over the money, but you don’t know what you’ll get. The chances of getting the very best and rarest players on Fifa, for example, are extremely low. This has led to comparisons with gambling – that loot boxes are like slot machines. In Belgium and the Netherlands loot boxes are already regulated as gambling, and now the UK government is considering the same thing.

Loot boxes are found in many of the popular video games children and adults play. Fifa – made by EA – for example, is a game with an age rating of 3+. Fortnite (12+) and Roblox (7+) also use them. A recent study showed that on Steam, a video game platform, more than 50 per cent of the top 100 grossing games contained loot boxes.

It was a period of my life when I was very unhappy but you could exchange money for a snapshot of happiness – and seeking that buzz of chance and rush got me through that difficult time

Some of these are simply cosmetic, providing the player with a new look for their character, and the player knows that. But some alter gameplay to make you more competitive. In Fifa’s case you can unlock better players – thereby spending money and hoping Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo will walk out. In other games you may get a better weapon, hoping to make you stronger in online play.

None of these “prizes” have a real-world value but children and adults can pump real-world money into them. With the government’s election promise to revisit the Gambling Act of 2005 this year, many are calling for loot boxes to be considered gambling and be regulated as such, including 45,000 gamers who have signed a petition calling on the government to act. There are deep concerns that loot boxes provide a gateway for children into problem gambling later on.

“It’s the unpredictable nature,” said Dr Matt Gaskell, clinical lead and consultant psychologist for the NHS Northern Gambling Service, describing what makes gambling addictive. “There are a few qualities that go into gambling products and that’s what we need to focus on rather than the money. There are certain characteristics, like the speed of them and the unpredictable pattern of rewards that are built into them. In psychology we call this a variable ratio schedule of reinforcement but in effect what that means is you can’t predict when the win is going to come. And that unpredictable pattern produces high levels of motivation and habitual behaviour, which is repeated in humans and animals.”

This is why we need to protect children from gambling products. It’s why someone under 18 cannot bet on sports or play games in casinos. Under 18s are particularly susceptible to these psychological processes. Along with this they have less understanding of what the value of money is, and it is rarely their own money. By exposing children to gambling mechanics, regardless of how much money they spend, the chance of creating problem gamblers in adulthood could increase.

Between the ages of 13-16 Jonathan was spending £100 three or four times a year on these boxes. Fifa used to release new cards a few times each year, but now it’s almost weekly. He would take his pocket money to the shops and buy Fifa point cards, redeem them on his PlayStation and then hide the cards so his parents never knew how much he was spending.

Jonathan also began watching videos on YouTube of other people opening packs of players. Some YouTubers make money opening hundreds of these packs online. One of these influencers spends £5,000 on packs in one go to show what players he gets, on another he spent £13,000. These videos have five and eight million views respectively and are watched all the more if they get one of the rare players such as Messi or Ronaldo.

Even when I watched these videos, and having very little interest in football, I found myself hoping for Messi to walk out; there was a buzz just watching someone else do it, let alone doing it myself.

“These videos are a huge problem,” said Jonathan. “It’s a massive display of packs, which just get cut down, so they look a lot more fun and have better results than they really do.”

Searching “loot box opening” on YouTube will reveal just how many people watch these videos, not just on Fifa but plenty of other games too. Jonathan had been watching these videos throughout his childhood, but the real problem started when he turned 16 and had access to his own debit card. “Suddenly they were just a couple of clicks away. No more sneakily buying a card somewhere in town. In that moment, wanting that rush, wanting that buzz, it could be fulfilled within a few clicks.”

The turning point came for Jonathan when he began to struggle with his personal life in his second year of A-Levels. In that September his mum was diagnosed with cancer. “It was a period of my life when I was very unhappy but I could exchange money for a snapshot of happiness. I would spend days upstairs pretending to revise for my exams and because of the difficult situation at home that rush and buzz got me through that period.”

We’ve got a situation where we don’t know whether loot box spending causes problem gambling or whether being a problem gambler causes loot box spending

Jonathan’s spending went from £20 to £40 to £50 until it reached its height and he was spending £80 four or five times a night on loot boxes. “The value of money was subsiding. I cared so much more about just finding a way to cope with what was going on in my life than I did about my savings. A huge thing in my mindset was ‘my future self will understand’. It was like one day when that future self is in a job somewhere, he’ll look back and he’ll know what I was going through and he’ll understand why I needed this money right now to cope.”

When Jonathan realised his spending was out of control, he believed he had spent £700. He told his mum at this point but that night when he tried to buy another pack his card was rejected. He realised he’d spent his total savings of £2,700.

“It’s very easy to lose track of how much you spend when you become a compulsive buyer of loot boxes,” he said.

He remembers the conversation with his parents when they went through his bank statements, and whenever he thinks of that conversation now, he thinks of Kerry Hopkins of EA comparing loot boxes to harmless Kinder Eggs in front of parliament last year. “It was a horrific conversation to have to have,” he said. “I was told by a parent that I had broken their heart with the money that I’d spent on loot boxes; that is the reality of the human cost and it’s happening again and again.”

Loot boxes are a specific problem for a specific group of games. For EA, 28 per cent of its revenue comes from in-game purchases. Dr David Zendle, at the University of York, is researching the links between video games and gambling. He was initially drawn into studying the link between video games and violence, but seeing there was no correlation there, he moved on to gambling expecting it to be the same story, but he was wrong. Through his research he has proved there is a correlation between loot boxes and problem gambling.

“Basically, you go out and spend a load of money on loot boxes,“ says Dr Zendle. “And that’s really exciting. And then you go out into the real world and you see something that looks very similar to a loot box. It has the same random reward mechanisms in the form of a slot machine or some other gambling product and because you’re used to the excitement or the rewards you get from loot boxes you are more likely to engage with the gambling product.”

However, he also concedes it’s possible that whatever makes a person a problem gambler is also making people buy loot boxes. There is simply not enough data. “At the moment we have no evidence of which of these two things is going on,” he said. “If the former is true, that loot box spending causes problem gambling that’s really bad news for society, because loot boxes are super accessible to children.”

He believes some sort of regulation is necessary, and says that by some estimates loot boxes are worth $30bn across the world.

Carolyn Harris MP, chair of the Gambling Related Harm all-party parliamentary group, is calling on government to regulate loot boxes as gambling. “We’re teaching children from a very young age that it’s normal to spend money on something that you’re not going to get anything from – which is gambling. But it’s not recognised as gambling.”

Harris became involved when she realised just how widespread and harmful gambling could be. After thinking it wasn’t much of an issue in her constituency of Swansea East, she came across a constituent who had asked her for financial help when he lost his wallet and had no money. That Christmas, while delivering a free dinner to an older gentleman in a pub, she saw the same constituent on the fruit machine. She found out that the only reason he was on the slot machine was because the bookies were closed on Christmas day.

“First, we need to make loot boxes gambling,” she said. “Then, anything associated with gambling should not be allowed for people under 18, so we’ll remove them from that platform. And if the game is for an 18-year-old it becomes the parents’ responsibility.”

With the House of Lords report recommending loot boxes be regulated as gambling, it seems likely the UK will follow the example of Belgium and the Netherlands. There are those that disagree with this one-size fits all approach. There are many loot boxes that have less or no damaging effects, and there are fears that if legislation is passed lawmakers will wash their hands of the issue, congratulate themselves and ignore whatever comes next.

Dr Andy Przybylski, director of research at the Oxford Internet Institute, believes this form of legislation would be like using a really large hammer to smash a nut, only to find out it’s the wrong nut. “We have a choice to make about whether we want this to be an evidenced based problem, with evidenced based solution,” he said. “Or if we really just want to put something we don’t understand out of mind and pat ourselves on the back.”

Instead of just blindly considering loot boxes as gambling, we should be pushing for a levy on data so that independent researchers can have access to video game-player data. Currently, video game companies such as EA are opaque, allowing very little outside scrutiny. This is something that, while he believes loot boxes should be regulated as gambling, Zendle agrees with.

“We’ve got a situation where we don’t know whether loot box spending causes problem gambling or whether being a problem gambler causes loot box spending,” he told me. “The only real way to find this out is with industry cooperation and access to industry data, which would be able to tell us this really quickly. But the industry is not playing ball, they’re basically just blocking us every single step of the way.”

And it’s not just EA. There is a broader issue of an industry about which very little independent research has been done. Zendle has released a new study showing several other possible links between video games and gambling that go beyond loot boxes. Social Casino games, for example, could be considered as gambling. These are basically gambling simulators. Zynga Games has many of these games. They are often slot machines with bright, attractive, recognisable themes such as Game of Thrones. They use a virtual, in-game currency with no real-world value and you can’t get real-world money out. Therefore, these are considered video games and not gambling. However, you can pump real money into these games if you want to buy more in-game credits.

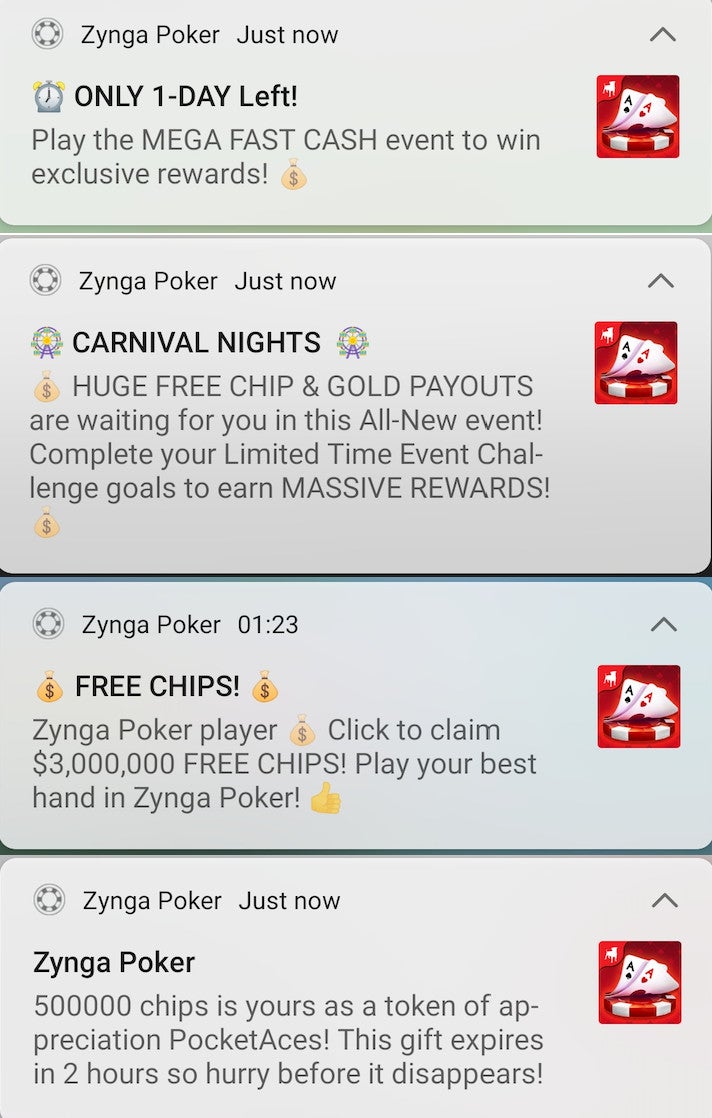

Zynga Poker can be played on Android by anyone aged 12+ and punishes you for not playing every day by reducing your bonus points, but congratulates you for playing every single day with extra free chips. Notifications pop up on the phone encouraging you to play and reminding you that you risk losing your “play streak” bonus. There is a fear these habits, even if real money is not used, will create a situation where gambling is normalised. According to Zendle, on Android there are more than 2,000 of these games, 97 per cent of which have an age rating of 12+ (on the Apple Store they are often 17+). A 12-year-old can legally download and play slots and poker. Zynga Poker has more than 50 million downloads on Android, and we have no idea what proportion of that number are children. On their website Zynga say: “The games are intended for an adult audience. The games do not offer 'real money gambling' or an opportunity to win real money or prizes.”

One mother told me of her 10-year-old managing to add her fingerprint to her phone so that she could buy £100 of credits on Roblox

So long as the games companies are not providing data and acting transparently there is no evidenced-based way to show the links between video games and gambling.

“There needs to be a push for a statutory levy on both data and money,” says Dr Przybylski. “The problem here with something like gambling in the UK is that the data and the participation of data sharing doesn’t really exist and the financial levy is a voluntary levy that mostly goes to treatment, very little of it goes to research and it’s voluntary and that’s wholly unacceptable.

“What needs to happen is transparency. If loot boxes go away we are no wiser about the role of games in our lives. Loot boxes might be a problem but I don’t think they’re a bigger problem than, say, bullying and anti-social behaviour and the toxic exclusionary culture inside these games, right? As parents and policy makers we don’t know enough about these games. There needs to be a national centre for video game research, and when loot boxes or trolling in games comes up then they can be investigated with the best possible data. If we had a levy on data and a levy for research then that wouldn’t impinge on the business model, but would give us insights into the lives of gamers.”

Video games are a huge part of our lives; whether that’s Bejeweled in your pocket, or Call of Duty on your PlayStation. Some estimates put the industry as being worth $100 billion worldwide. They are magnificent forms of art, and storytelling and play and are an excellent way to socialise. The rise of Esports could well be huge and it’s all positive but without the data and independent research we run the risk of many more “loot box crises”.

“I am not anti-gambling I can’t emphasise that enough,” Ms Harris said. “If the Derby was on today, I would have the newspaper and I would be putting a bet on a horse. But I am anti-anything which prays on vulnerable people and causes them harm and distress, and in some cases causes them to take their own lives.”

We do not understand the relationship between loot boxes and problem gambling, but we do know there is a link. We also know children are exposed to these, and other mechanics, in games that are marketed directly to them.

EA is engaging in cross-industry discussions with researchers, academics and governments with the intention of sharing funding and player data, but it believes nothing in its games constitutes gambling. EA agrees with the Gambling Commission’s assessment that loot boxes are not gambling unless winnings can be “cashed out”.

“We want parents to have control over those decisions,” it said. “The majority of gamers play EA games on one of the major video game consoles. Each console has family controls, which allow parents or guardians to manage the type of content their children access, and how much time their children can spend playing games.”

Jonathan takes full responsibility for what he did and the decisions he made, but it was a time in his life when he needed protecting from the lure of loot boxes. He was lucky he had a solid network of friends and family around and, after a small relapse, he hasn’t spent a penny on loot boxes since, instead choosing to tell his story. He points me to a Twitter survey he ran, suggesting that 60 per cent of his followers didn’t even know parental controls existed.

Another question is: if a game has an age rating below 18 then why should the parent need to add controls? One mother told me of her 10-year-old managing to add her fingerprint to her phone so she could buy £100 of credits on Roblox, a 7+ game with a large child following, which includes loot boxes. In 2019, in the UK, 1.5 million children played the game. Should a parent need to put controls in place on a 3+ or 7+ game?

Jonathan, now 21 and studying Interactive Media at the University of York, released a video on YouTube talking about his addiction. Since then he has received many messages from people sharing their stories, which he says he can’t look at for long because it is too emotionally draining. On average the people that contact Jonathan with their stories are aged 15-23, some younger, some older.

“Loot boxes can have a devastating impact on someone’s life – that’s what we’re talking about here. And it’s usually someone in a vulnerable situation who uses loot boxes as a way to cope.”

If you are experiencing feelings of distress and isolation, or are struggling to cope, The Samaritans offers support; you can speak to someone for free over the phone, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch

If you are based in the US, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call National Suicide Prevention Helpline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255). The Helpline is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you’re struggling with any of the issues mentioned in this article, GamCare operates the National Gambling Helpline, providing information, advice and support for anyone affected by gambling problems. Advisers are available 24 hours a day on Freephone 0808 8020 133 or via web chat at gamcare.org.uk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments