The quest to find the loneliest whale in the world

A whale called 52 has roamed the oceans for decades seeking companionship – its haunting cries unanswered. James Rampton talks to the man who has gone to look for it

Stunned by what they were hearing one day in 1989, the operatives working on the US navy’s top-secret, Cold War-era acoustic surveillance system may well have turned to each other and said: “It’s sound, Jim, but not as we know it.”

They had detected a mysterious signal in the Pacific Ocean. The unidentifiable sound, picked up by the highly confidential network of listening devices constructed in the 1950s to monitor Soviet submarines, resonated through the water at a very unusual 52 Hertz. The noise, which was a pitch or two above the lowest note on a tuba, did not emanate from a submarine. It completely stumped the US navy.

Dr William Watkins, a marine biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, stepped in to solve the mystery. He deduced that the sound was emitted by an enigmatic, solo whale. The pitch was much higher than most whales, which “sing” between 17 and 18 Hertz.

The marine biologist believed that the creature, which became known in scientific circles as “the 52 Hertz Whale”, had roamed the oceans on its own for decades. As it strove to find a companion, the animal cried out at a frequency that was different from any other whale. The call, from a usually highly sociable creature, was a sound that no human being had ever heard before. The lonely plea, which could travel up to 13,000 miles, haunted the oceans unanswered.

Watkins’s discovery instantly caught the public imagination worldwide. People started getting tattoos of “52” on their back and writing songs about this solitary creature. Before you could say “the headline writers were having a whale of a time”, newspapers dubbed it: “The Loneliest Whale in the World.”

The story also caught the eye – and ear – of the American filmmaker Joshua Zeman. Talking to The Independent from the US, the director explains what first drew him to this remarkable story. “I had broken up with a girl and was feeling very sorry for myself. So I went to an artists’ colony called MacDowell.

“There was a gentleman there named Vint Virga, who was an animal behaviourist and had written a book called The Soul of All Living Creatures. It’s about what we humans can learn about ourselves from our experiences with animals. It had a chapter about the loneliest whale. I was feeling sorry for myself, and I was really moved by this chapter.”

Zeman continues: “I went to breakfast the next morning, and I was sitting with all these artists. I told them, ‘Oh my God, this story about the whale is so fascinating. It's about man's existential crisis.’”

When their time at the colony was over, Zeman “got a call from one of the artists who said, ‘oh, you remember you were telling us about the loneliest whale that morning over breakfast? Well, I did a painting of it’. Then another artist called me up and said, ‘oh, I wrote a poem about it.’ And then another told me, ‘I did a piece of sculpture about it.’

“It was so interesting to me that all these people had been so moved by the story of this lonely whale. And then I went online, and I saw that the story had gone viral. I was just so fascinated by it. What was it about this story that elicited such a reaction?”

You feel for the whale. People can relate to it. You hear about this one whale who’s never made any friends, and that really, really resonates with people

To Zeman and millions of others, 52 represented so much more than just a solitary whale. It stood for the indomitable desire of creatures to search for company. It also became emblematic of the current mass outbreak of human loneliness. Ironically, as the world has become more interconnected, individuals have become more isolated.

There and then, Zeman decided to resolve the enigma and go on a quest to find the whale. Before doing so, though, he had to swim through an ocean of questions: is 52 still alive? If so, can he be located? Would the search for a single whale in the vast expanse of the world’s oceans be harder than finding a needle in a haystack?

So Zeman started a crowd-funding campaign to make a film entitled The Loneliest Whale: The Search For 52. He succeeded in raising an impressive $450,000 through Kickstarter. He was helped enormously with a $50,000 donation from movie star and environmental activist Leonardo DiCaprio. He became an executive producer on the documentary, which is now available as a digital download.

Why has this lonesome whale struck such a chord with people right around the world? Typically, we humans have managed to make it all about us. “It’s not about science,” says Dr Christopher Clark, a senior scientist at Cornell University. “It’s about us and our inability to communicate and our own isolation. It’s about human experience and is a reflection of who we are. This story is about all of us.”

Kate Micucci, a musician who has written a song about the Loneliest Whale, chips in: “You feel for the whale. People can relate to it. You hear about this one whale who’s never made any friends, and that really, really resonates with people. They understand it. Everybody feels like an outsider at some point in their life. I think that’s why so many people care about it.”

The sheer poignancy of 52’s call also chimes with people. Listening to the plaintive cry ring out, Joseph George, retired chief of the US navy Integrated Undersea Surveillance System, responds: “If that isn’t a call for mamma, I don’t know what is.”

Social media, the atomisation of society brought about by the internet, the destruction of the extended family and the pandemic have caused an epidemic of loneliness

Zeman contends that the story has particular potency because we have a special bond with whales. “When I started to pitch this to friends, they would freak out, they would cry, or they would get goosebumps. I wanted to know why we felt such a connection with this whale. Was it because we were so disconnected from each other? Searching for a lonely creature in the middle of a great void of nothingness is like our own existential crisis.

“Our over-reliance on social media, the atomisation of society brought about by the internet, the destruction of the extended family and of course the pandemic have caused an epidemic of loneliness. But dwelling on that too much got really depressing. So I said to myself, ‘I’m going to make the happiest goddamn lonely whale movie ever!’”

Accentuating the positive, “led me down this path of looking at humanity and our connection with whales. People talk about Lonesome George, the giant Galapagos tortoise, but he doesn't have the same kind of emotional connection with people as whales do.”

We have such a strong link with whales, Zeman carries on, “because they are so big and we're humbled in their presence. Human beings are unbelievably selfish and self-involved creatures. We think we’re the biggest and best in the animal kingdom.

“Then suddenly, in the presence of a whale, which is so spiritual and mythological, we are reduced to humble servants. A whale levels the playing field in a way no other animal can. Then there is their sentience. They can speak to us – we just can’t understand them. And this idea of them swimming through the oceans calling out really mimics our own experience.”

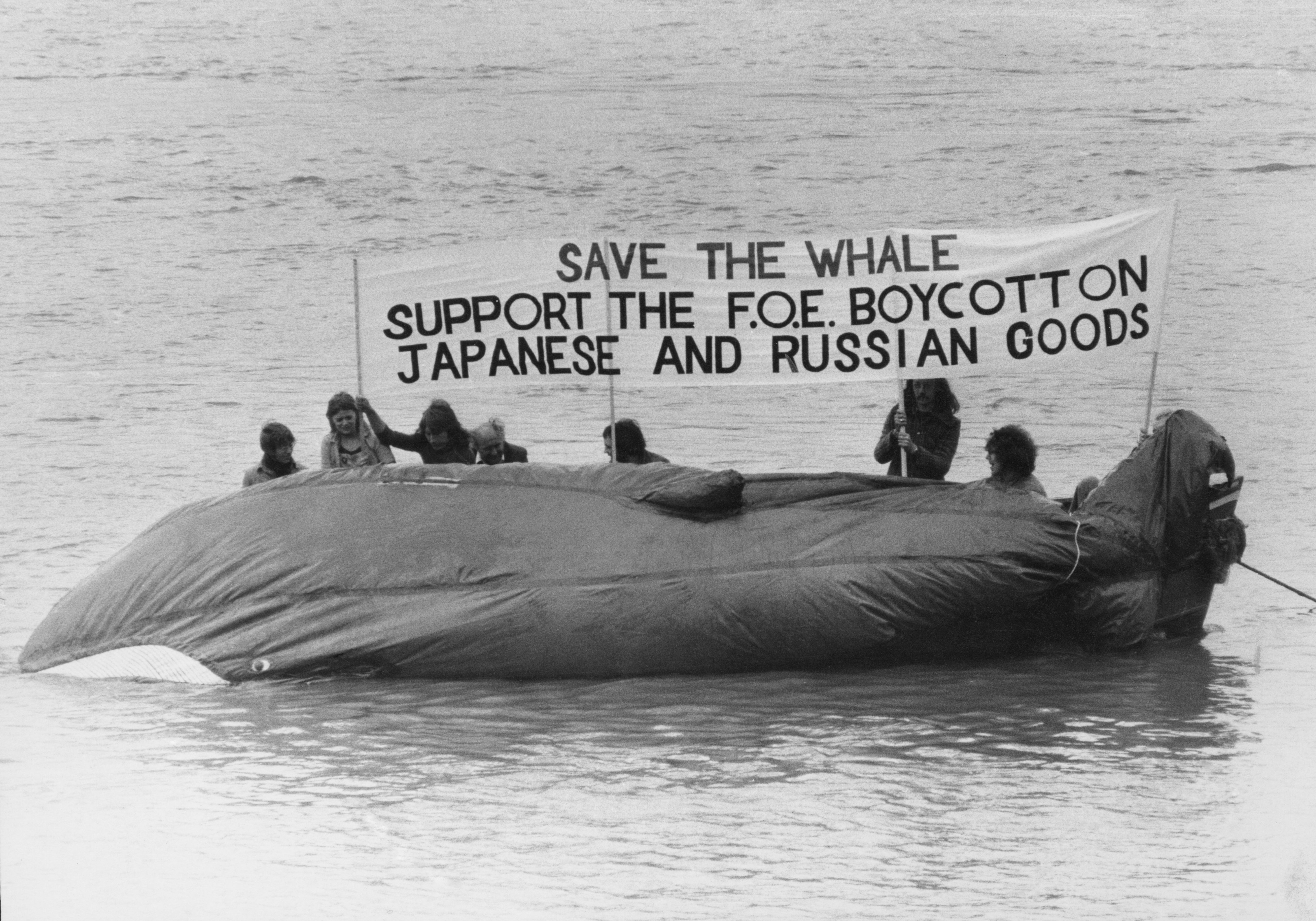

One hundred years ago, “there was no creature that was as vilified as a whale. But we have really turned that situation around over the past century. Back then, we were killing ourselves to kill whales, and now we're killing ourselves to save whales. There has been no other creature that that's had such a profound effect on us as the whale.”

Zeman, who spent four painstaking years making The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52, expands on our deep relationship with the creature. He says that when as a child he first saw a whale leaping out of the water, “I felt I was in the presence of something greater than myself. That sense of mystery has always been there.

You can draw a direct line from the Save the Whale movement through to the green movement to the fight against climate change today

“We’ve always sought the great whale, whether to slaughter it or now to save it; from Jonah who found redemption in the belly of a whale to Captain Ahab who found the ultimate adversary in the hunt for a whale. These epic stories are ingrained in our culture, our consciousness.”

Philosopher David Rothenberg, a distinguished professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, echoes this sentiment: “Even contemplating whales is to dare to reach towards greatness, to think about something far more vast than humans could ever be. We should be going after all great mysteries like this.”

During the 19th century, our relationship with whales was very different. Slaughtering whales was big business. Whale oil lit up the Industrial Revolution. It was the main source of fuel for lamps and lubrication. By the 1960s, 33,000 whales a year were being butchered. Almost all the large whales in the ocean had been wiped out.

But all that changed in 1970 when a bio-acoustician called Dr Roger Payne discovered that humpback whales could sing. He recalls that when he first heard their songs, “it was an extremely emotional experience. I thought, my God, if that doesn’t get the world interested in whales, nothing will.”

He recorded the sound and produced an album entitled Songs of the Humpback Whale, which went multiplatinum and became the bestselling environmental album of all time. National Geographic asked for 10.5 million copies of the LP, the largest single order in recording history. The popularity of the album enabled people for the first time to grasp that whales are highly intelligent. It prompted the global Save the Whale movement. It also inspired the foundation of Greenpeace in 1971 and the 1972 United Nations conference on the human environment. This led to a 10-year global moratorium on commercial whaling and reduced the slaughter of the animals by 99 per cent.

Now Payne muses: “We probably would never have saved the whales unless we’d heard them sing. It made people care, and when people care, they can change the world.”

The Save the Whale movement was certainly influential. Zeman says: “When people heard the album, they said, ‘oh my God, those creatures make an angelic sound. We can’t kill them!’

“You can draw a direct line from the Save the Whale movement through to the green movement to the fight against climate change today. Things are unbelievably horrible now, but imagine how much worse they would be if we hadn’t had the Save the Whale movement.”

All the same, isn’t there still a danger of us anthropomorphising the whale? Zeman admits that “our gut feeling about whales doesn’t always comport with science. I’d say to the scientists, ‘oh, come on, these creatures must be sentient. They have cooperative feeding, child-rearing, all these things.’

“However, it really pissed the scientists off when I would talk about the loneliest whale. They would reply, ‘You have no basis for saying that. As a scientist, this is really upsetting. You are anthropomorphising this creature and you're assigning human attributes to it when they may not be there’. I would reply, ‘you may say that from a scientific standpoint, but in your heart, do you think there could be a lonely whale?’ The reason they would never go there is because of the hippie pseudoscience of the 1970s that really went down the whale rabbit hole.

“Yet at the same time, let's look at a whale's brain structure. Let's look at the notion of spindle cells, which are found in whales, upper primates, elephants, and giraffes. The coalescing of spindle cells allows for cooperative behaviour. That's what creates social networks. The whales are saying, ‘let’s create social networks to help us rear and protect our baby calves’.”

A cross between Jaws, Moby Dick and Free Willy, The Loneliest Whale: The Search For 52 makes for a gripping quest story. Zeman and his crew of scientists set out on their felicitously named boat, Truth, in an attempt to hear 52 off the coast of southern California. The team clearly takes great joy in its work. They wear a broad smile wherever they see an enormous whale gliding with effortless power through the water beside their vessel. Despite decades of familiarity with the awe-inspiring creatures, they never lose that sense of wonder.

Dr Christina Connett, the chief curator at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, outlines the unique buzz you experience when searching for a whale. “There is that thrill, the thrill of discovery, the thrill of the exploration itself, the thrill of the journey. To be a true explorer, you have to be willing to put yourself at risk, and that has to be thrilling or you’re not going to succeed.”

The quest is certainly an exhilarating element of the documentary. But can you ever change people’s minds with a single film? Zeman thinks so. “Look at Blackfish, the documentary about the orca in SeaWorld. That not only changed people’s minds, it changed the whole aquatic theme park world. Suddenly they were saying, ‘OK, we have to rethink how we do this’.”

The director reflects on what he has taken from making The Loneliest Whale: “It was a crazy idea to go out and search for whale, but it’s changed me as a human being for ever.

“I've never learned more about humanity than I did from this whale. It sounds crazy, but a whale taught me to be a better human being. And that's because the whale taught me to care, to have empathy and above all to listen.

We are all in awe of what happens in the sea and fascinated by the idea that there is this mystery noise underwater – 52 Hertz is a sound that is not like anything else we know

“My girlfriend might disagree with you! But I am a better listener than I was beforehand. Obviously, I had a lot to learn. But the key to solving loneliness is to be a better listener. That is not only the key to loneliness, but it’s probably the key to enriching relationships in life.”

That also applies to international relations. The world would be greatly improved if countries listened to each other a bit more. “That would be far better than yelling and screaming at each other and never listening to what the other person is saying.”

On a wider scale, The Loneliest Whale bears out former US secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld’s famous remark that, “there are known unknowns”. As human beings, we often see ourselves as masters of the universe. But it does us no harm to be reminded every once in a while that we do not know everything.

John Hildebrand, distinguished professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who leads Zeman’s expedition, asserts: “People assume we know more than we actually do. There’s the bit we can see, whatever is happening on the surface. But then there is the 95 per cent that we can’t see. There’s just so much we don’t know.

“52 Hertz is still a mystery. But I think it’s important to do things where you don’t know what the answer is going to be because that’s when you really learn something.”

Rothenberg celebrates the fact that we still have so much to discover about our planet. He says: “The Loneliest Whale gives us the sense that humans really can touch upon something very mysterious that we barely understand. We are all in awe of what happens in the sea and fascinated by the idea that there is this mystery noise underwater: 52 Hertz is a sound that is not like anything else we know. It’s amazing to think that even in this day, we are listening all over the ocean and are still hearing things that we cannot explain.”

Zeman also rejoices in the fact that so much of our world remains unknown. “In the ocean, what we can hear is a far more powerful than what we can see. It resonates with a mysterious beauty that we’re only just beginning to understand.

“I love the fact that there are still so many mysteries out there for us to explore. We know more about the surface of the moon than we do about our own oceans.”

He adds: “That’s why I was so eager to go on a quest to find the whale. Most of our searches nowadays are online. I can search for all the answers in the little search bar on my computer. But it’s really important for knowledge, creativity and our thirst to grow that we realise there are so many more mysteries out there. There are so many things we must go out and find for ourselves.

“Siri does not have all the answers. Alexa does not have all the answers.”

‘The Loneliest Whale: The Search For 52’ is available as a digital download from 4 April and on DVD from 11 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks