In the age of Wikipedia, is it better to study everything?

The one-track mind of the current education system is flawed, says Andy Martin. The London Interdisciplinary School, the first new university to open in more than 50 years, aims to put it right

Students are missing out. But it has nothing to do with not going to lectures – or wild parties either (except the illegal kind). The problem is so deep and yet so manifest, so visible, so normal, that most people don’t even notice it. Higher education is training you up to be an idiot savant. It’s not about what you learn, it’s about everything you choose – or are forced – not to learn. This learned ignorance starts at school and then gets reinforced and locked in at college.

Your life is assumed to be linear. Even before you know what you really want to do with your life, you have to specialise and commit to becoming an airline pilot or a plumber or studying humanities or going into the sciences. Like some kind of premature, pint-sized professor. And then you come off the tracks at a certain point when you realise everything else you are automatically excluding. A higher education is only a higher form of ignorance. Increasingly, we teach more and more about less and less. Most classic university courses, especially at Oxford and Cambridge, require students to repress the instinctive desire for unlimited intellectual exploration. Often they graduate feeling frustrated and lost (assuming they aren’t thoroughly depressed beforehand).

Fortunately, there is a new kid on the academic block, the London Interdisciplinary School, which finally aims to satisfy that basic instinct, to find out more about the world rather than fixate on a narrow and inward-looking curriculum. As Wittgenstein said: “The world is everything that is the case … the totality of facts.” The London Interdisciplinary School (LIS for short), launching later this year, can’t quite offer a degree in omniscience, but it would like to. “You can’t do everything about everything,” says Carl Gombrich, one of the forces behind the new institution. “But you can create your own network – that mitigates to some extent the sorrow.” LIS offers a higher education in the age of Wikipedia. I suspect it will make the status quo look increasingly archaic, analogue and out of touch.

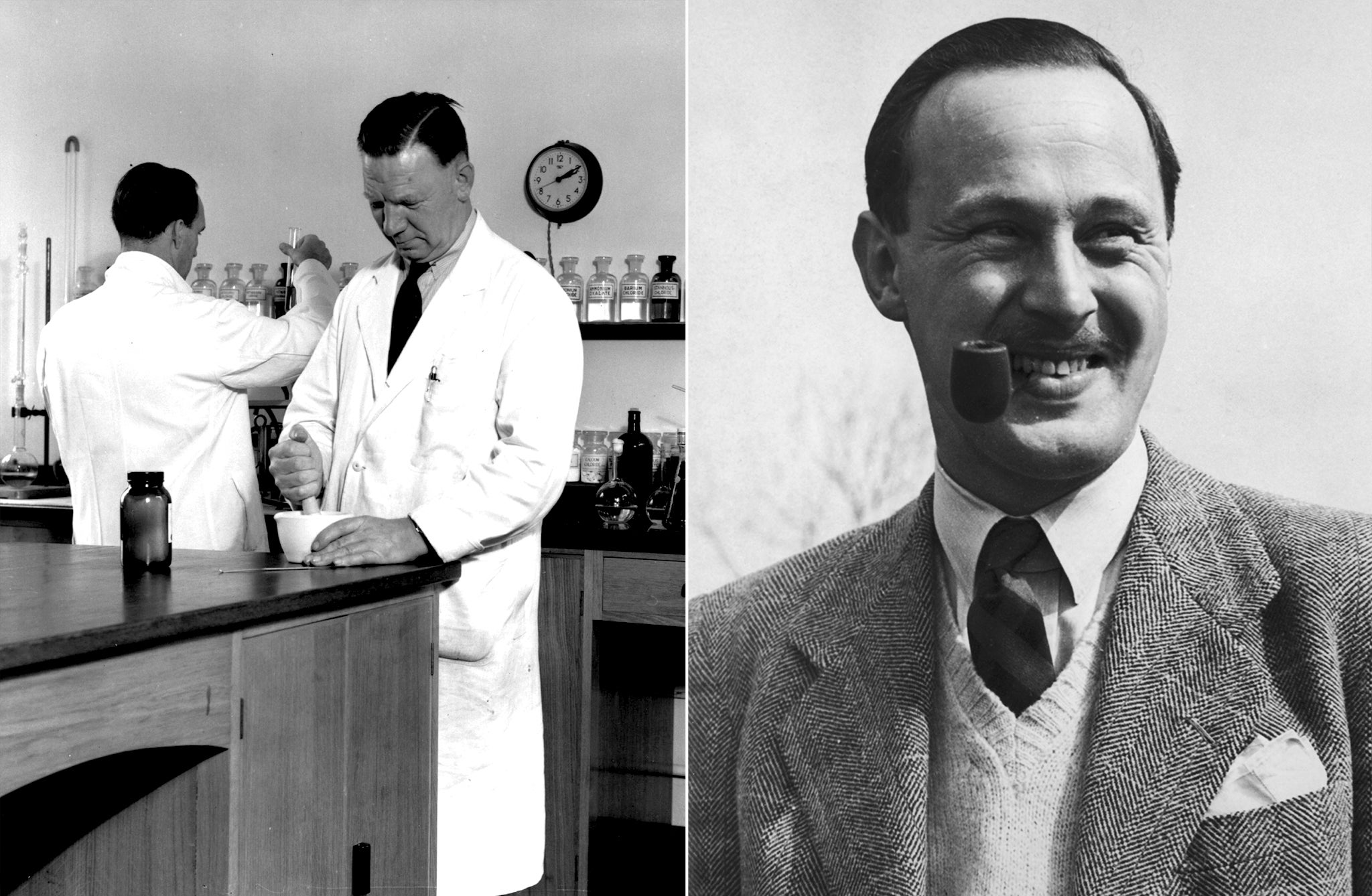

Back in the 1950s, CP Snow noticed the divide into “Two Cultures”. He saw a world of people in white coats, on the one hand – the scientists – and the dons in tweed jackets with elbow patches and pipes on the other – the arts guys, who were into literature and history and philosophy. And never the twain shall meet, except across the senior common room or at high table. (Snow ignored the great and growing realm of social sciences.)

The split was reflected at school level, especially in the sixth form, where the students doing arts courses on the humanities side looked down on the lab rats and the science-oriented students returned the favour and were happy to be referred to as “nerds” or “geeks” or “techies”. School was schismatic. Each side scorned the other. It was intellectual apartheid.

The weird thing for me growing up was that I was on the arts side and gravitated towards the elbow patches and (in my case) the beret, while my twin brother (really – he is not a metaphor) became a rocket scientist who did a PhD on X-ray astronomy. So, whether I liked it or not, I picked up enough quantum mechanics and relativity theory and cosmology to get by (I’m not sure my twin brother ever got beyond very elementary French though, which he has now completely forgotten anyway).

The raison d’être of the LIS is to enable the next generation to overcome the great divide and be more of a grand synthesis of me and my twin – why ignore and omit and repress vast acres of potential knowledge? Physics can be fun too. As can Proust. Do we have to choose?

Western higher education as we have it now harks back to the Academy of ancient Athens, founded by Plato, who wanted to educate “philosopher-kings” to rule the republic – but then philosophy incorporated the true, the good and the beautiful (and, on a more practical note, music, poetry, mathematics, dialectics, gymnastics – and possibly wrestling, Plato’s own favoured sport). Socrates, his mentor and inspiration, said, “I know that I know nothing”, which was supposed to give him an edge over all those (like politicians or craftsmen) who thought they at least knew something. But that was, subtly, a dig at everyone who specialised too soon and was, paradoxically, a plea to go out and try and learn about everything, at least to be open to and be able to engage with anything.

The Renaissance in Europe took this vision seriously and in exploring the ancient archive (mediated through Islamic scholars) and trying to apply it in the modern world produced such classic “Renaissance men” as Leonardo da Vinci, an uomo universale who knew as much about science as art and invented flying machines and a mechanical lion. But Leonardo may have had no formal education and Renaissance women were excluded from university. Shakespeare’s line in Hamlet, which is partly about the limitations of the student life (the bard contented himself with a grammar school education), “There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy”, is a critique of how narrow university education had become. Serious Renaissance scholars craved “more” – to maximise their knowledge, to seek the “totality of facts”.

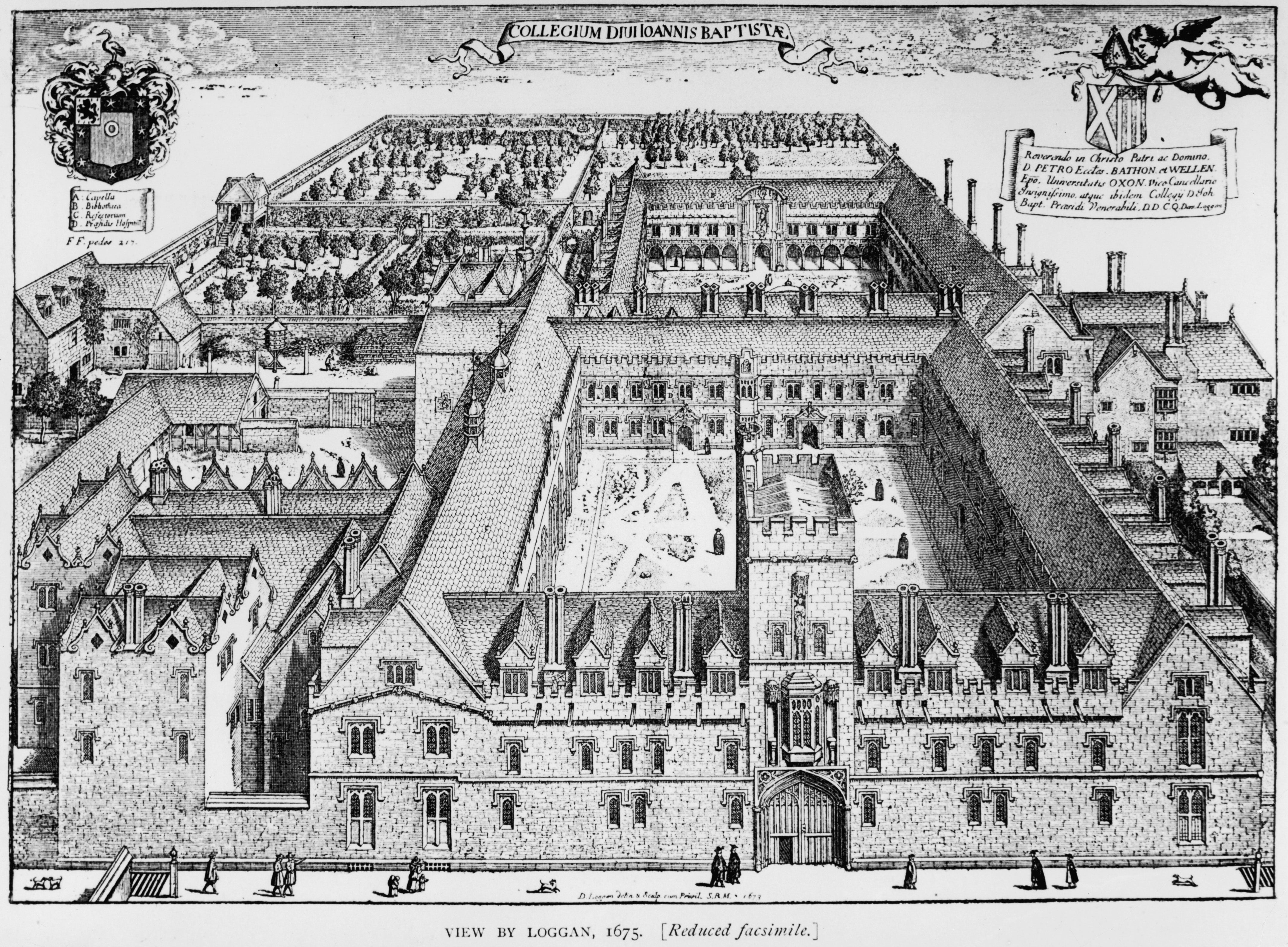

The very idea of a “university” – a city that contains the universe – was always a little optimistic, verging on utopian. Once, going back to the 11th-century foundation of the university in Paris, Bologna and Oxford, the typical students of the era studied everything. There was only one course, which included everything it was deemed worth knowing (mostly theology, alongside the “seven liberal arts”). But as universities evolved and expanded they also shrank their intellectual horizons. Yes, there were more courses, but you had to restrict what you were interested in. In the culture at large, with the rise of capitalism, there was a division of labour. We were supposed to be good at one thing, not everything.

Ed Fidoe, who is one of the founders of LIS, rightly heaps scorn on the “personal statement” that all would-be students have to include in their application. “You have to say how much you want to do this one thing. How your whole life has led up to this and only this.” And, he argues, schools try to fulfil this requirement. “How do you change that stranglehold?”

We used to produce polymaths, who would have a decent shot at anything and everything. Aristotle, as Peter Burke points out in his recent book The Polymath, “is most often remembered as a philosopher concerned with logic, ethics and metaphysics, but he also wrote on mathematics, rhetoric, poetry, political theory, physics, cosmology, anatomy, physiology, natural history and zoology”. Or take Blaise Pascal, for example, in the 17th century: not only a theologian and philosopher (and author of the Pensées) but a mathematician who came up with an early form of calculus and one of the first computers to boot (and he died at 39).

The 17th-century Jesuit scholar, Athanasius Kircher, has been called “the last man to know everything”. By the time of the Encyclopédie (“A Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts” – derived from the concept of enkuklios paideia, or “rounded education”) in the 18th century, in which writers like Rousseau and Diderot heroically bestrode the Enlightenment, we were already waving farewell to the ideal of knowing it all and to the figure of the “philosophe” – who was a generalist, not a specialist, before the industrialisation of philosophy. Noble exceptions apart, from the 19th century on, we became humble workers on an infinite assembly line of which we could only ever see a small part.

No wonder then that modern-day students end up feeling “alienated” as Carl Gombrich says. It was the word Karl Marx used about how the proletariat must feel, disconnected from their own work. And Gombrich speaks with something of the fervour of a revolutionary, not about communism, but about a much broader, more inclusive approach to education, which involves “network thinking”. The idea of a network, connecting up disconnected, is probably the governing metaphor of our age. LIS is taking it literally.

“This would have been impossible without the internet,” says Gombrich. “People are learning in a different way, using YouTube and Wikipedia. They can make their own connections. We can’t insist that they have to read a book. If they are doing something on literature then we don’t exclude the book. But we have to adapt and adjust to the digital.”

Gombrich was originally a professor at UCL where he spent many years setting up a freewheeling “arts and science” course in which you could study organic chemistry and Arabic or Mandarin. “Our students got the top marks,” he says proudly. “We fended off the naysayers and the negativity.”

I can imagine how much resistance he ran into. Having witnessed the US system – or “system-less system” as it has been described – at close quarters at several different universities, I have been impressed by the sheer range of teaching on offer there especially in the first year (it tends to get narrower as it goes on, especially at the older institutions). But when I floated something similar at Cambridge, I got beaten up (or at least beaten down) by assorted French specialists and Latin specialists and Greek specialists – all of whom thought students should be doing more French or more Latin or more Greek. There was no notion of the big picture. There aren’t just two cultures: the university has fragmented into self-enclosed “disciplines”, governed by a silo mentality.

The “new” universities of the Sixties (such as Sussex, Essex and East Anglia) shook things up for a while and tried to “redraw the map of learning”. But the stodgy old institutions managed to pour inertia on new initiatives. Ed Fidoe, who studied mechanical engineering at Imperial College, says: “It was impossible to change the old university. So we thought we had better invent a new one.” He had the previous experience of setting up a new school in London, School 21, “so the idea didn’t seem too mad.”

Fidoe himself went on to do a business degree after Imperial, but then went off on a tangent into theatre and became an actor and producer. He is, in the jargon, a multi-hyphenate. He gives Richard Jenkins as an example, from his own experience at Imperial, of a brilliant student who was not well served by his university. “He was one the great engineers – a genius – and he was made to re-do an entire year.” Jenkins, having already built his own boat and sailed the Atlantic at the age of 16, went on after college to set a new land speed record for a wind-powered vehicle. “As a student,” says Fidoe, “you’re worried about whether you’re getting it wrong – not whether they are.”

Following the white paper of 2016 on “challenger universities”, Fidoe and Gombrich and Chris Persson have spent the last few years jumping through the many hoops of the certifying authorities, who have finally granted them university status and degree-awarding powers. The London Interdiscplinary School is the first new university in over 50 years. The initial cohort of around 100 students are due to take their seats in lecture halls on the campus in Whitechapel, just off Brick Lane, this September. They will share a broad compulsory foundation year and then there will be convergence and divergence. But they will be held together by the imperative of problem-solving.

Gombrich speaks of a “new Renaissance”, uniting teaching and cutting-edge research, and producing a generation of polymaths. “There’s a value – a certain cognitive effort – in learning anything,” he says. “But what we really want is wide-achievers as well as high-achievers.” The LIS ethos was inspired in part by the philosopher Karl Popper’s theory of knowledge as “conjecture and refutation”. “You start with a real problem and then bring to bear whatever you need to know. It could be maths or it could be writing. But it also leaves open the possibility that you go in different directions.”

One topic that will provide an initial focus is the question of happiness. It can be approached as a health issue, or in terms of genetics or cognitive science or linguistics or anthropology. “And there is a whole philosophy of melancholy,” says Gombrich. “And anyway what’s wrong with unhappiness?” Other “problems” that are on the agenda are climate change, AI and ethics, public health, and education itself. “They are big chunky problems, and they are all interdisciplinary. You can’t ignore maths or science in the age of Covid.”

He stresses that this is not a “pick’n’mix” approach – a criticism sometimes levelled at US colleges. But there is a degree of convergence with the US. Professor Joy Connolly, formerly provost of the Graduate Centre at the City University of New York, now president of the American Council of Learned Societies, says that “across the country it’s interdisciplinary programmes that are working best: food studies, environmental justice, peace studies, political economics, translation, public health studies/policy”. And there is another common denominator with the American business school. LIS is looking for students who are capable and motivated, but also entrepreneurial-minded. They offer internships across all three years. Students are encouraged to get out of the ivory tower. And their business partners are invited in too. “These are real world problems,” says Gombrich. “There must be a bit of ivory tower – a degree of seclusion – but whatever they learn in an academic context is important outside too.”

Could it all be done remotely, with students sitting in front of laptops? Ed Fidoe accepts that “there are many things you can do online. And Covid changes it a bit. But there’s still a need to come together in a physical way. In real spaces. To feel part of something. ‘I want to go there and do that.’”

The interdisciplinary approach is practical, not purely theoretical. It is more hands-on than Oxbridge. Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was a depiction of the insanity that arises out of the schism in education – even a fully paid-up philosopher ought to be able to fix his own motorcycle. As Wittgenstein wisely said, if you want to be a philosopher, become a car mechanic – don’t just sit around reading philosophy. At LIS, I like to imagine, the philosophers of the future won’t mind getting their hands dirty.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments