What was life like behind the Iron Curtain? In 1991, we went to find out...

If they were going to visit eastern Europe before the tidal wave of capitalism hit, Mick O'Hare and his wife had to act quickly – but nothing could have prepared them for what they found

When Boris Yeltsin stood on a tank in Moscow in August 1991 and denounced the coup attempting to overthrow president Mikhail Gorbachev and reinstate one-party communist rule in the Soviet Union, he not only saved his nation (albeit briefly), he also saved my proverbial trip of a lifetime.

After the Berlin Wall fell in late 1989 and communist governments throughout eastern Europe tumbled domino-like, my partner and I hatched half a plan. If we were going to visit eastern Europe and see how life had been lived behind the Iron Curtain, we had to go pretty quickly. Capitalism was going to hit like a tidal wave sweeping away the ordinary lives of half a continent in a deluge of consumerism. Thirty years ago, in the autumn of 1991, Sally had qualified as a physiotherapist and I jacked in my job on a motorsport magazine. We had the visas and travellers’ cheques. And then Gorbachev was placed under house arrest, tanks rumbled onto the streets of Moscow and the citizens of eastern Europe peered nervously over their shoulders. Were the old days returning?

Thankfully Yeltsin stepped up to the plate. And we stepped onto a flight to Salzburg. Thirty years later it’s strange recalling how crossing the border from Austria felt. The Czech Republic is now just another country, but three decades ago we were crossing what had recently been a forbidden frontier. Those borders on our pre-1989 maps looked oppressive, marked with black crosses and a thick red line. The watchtowers were still in place, the guards still wore the uniforms of the “bad guys” from spy movies. The trains were old, unkempt, covered in Russian script and clunked into sidings where armed officers checked your documentation. But then, unlike in those old movies, you were waved through, unfettered, into their reborn country…

We really were in Czechoslovakia – the Velvet Divorce was still more than a year away – each with 800 quid in our pockets and not a clue about anything except what we read in our Rough Guides (the World Wide Web was only created that same year). We knew of nobody who had visited such a place.

We still have our Czech (and Slovak) phrasebook and know the words for train (vlak), castle (hrad) and beer (pivo) although surprisingly most transactions with non-Czech speakers were conducted in German, then the second language of most Czechoslovaks. All had learned Russian at school but, for obvious reasons, remained reluctant to use it. So my excruciating, failed O-level German it was (plus the phrase books).

And German was the language in which we were harangued on the train shortly after crossing from Austria by a fellow traveller still seemingly committed to the communist cause. He stood before us denouncing us as vultures ready to pick over the corpse of socialism and demanding we leave. “Is this how it’s going to be?” I asked Sally, rather concerned. It wasn't, it never happened again. Welcome to eastern Europe.

We were trundling across Bohemia and Moravia heading for the biggest city in Slovakia’s east, Košice, mere kilometres from the Soviet border. We holed up in its grandest hotel (foreign tourists weren’t allowed to stay elsewhere) which set us back £4 per night, toilet and bathroom shared. But at least the guest facilities were an improvement on those attached to the hotel’s public bar. Love, money, not even gunpoint would have made me visit them more than once. Indeed, in all honesty, toilets proved to be a stumbling block – anything public was generally best avoided. We travelled for a while with an American who refused to eat and sipped only minuscule amounts of water for 24 hours before a train journey so he could avoid using the facilities.

Hotels, too, were often perplexing. In Cluj-Napoca in northern Romania, we were placed on the top floor of an enormous Stalinist Fifties edifice in what seemed to be an otherwise totally empty, echoing building. Sometimes at night, we thought we heard people pass by in the corridor but apart from the woman on reception who apparently never left her desk whatever the hour, we saw no one. The views over the town, however, were fabulous.

In Banská Bystrica, in Slovakia, in one of the few places unconcerned about our marital status (or lack, thereof), we were told we’d be in rooms on the third floor because “they aren’t bugged, and you are young”. The implication seemed to be we’d want to have sex without the secret police listening in. Was it a joke? Surely the Cold War was over. And in Bratislava we were awoken in the early hours when hotel reception decided a lone Bulgarian traveller would be sharing with us. He changed into a green kimono and sat reading in the corner of our bedroom. Meanwhile, it was a hot evening, and we’d chosen to wear nothing. Come dawn our bladders were straining. An uncomfortable night all round.

There was no sign, no advertising of any kind to alert would-be hat-buyers, but yet here was a shop stocked with everything from berets to boaters

But back to Košice. The city’s station was a delight – locomotives arriving from all over eastern Europe and beyond – Moscow, Kraków, Zagreb, Kiev – and it’s where we learnt the Czechoslovak custom of an entire train disembarking to pile into the station buffet while the locomotive waited on the platform. The queues were orderly but moved rapidly as a half litre of pilsner and a sausage in Rožky bread was ordered and consumed before the carriages were re-embarked for the onward journey. Whole trainloads were processed in about seven minutes.

Košice was the first place, among many, where we experienced restaurant lights being turned off when the staff wanted to leave, usually around 8pm. There was no pressing you for coffee and liqueurs, they were being paid whether you were there or not. The profit margin driving businesses in capitalist societies had given us a differing sense of necessity, one completely absent in populations brought up on a centralised command economy. Restaurants were frequently “fully booked”, yet we would pass by later to see the “reserved” tables had been unoccupied all evening. There was no monetary imperative for the restaurant to operate. We wondered if the kitchens even had food. Similarly when Sally wanted to buy a beret in Budapest we were directed into a residential courtyard. There was no sign, no advertising of any kind to alert would-be hat-buyers, but yet here was a shop stocked with everything from berets to boaters. The waiters and milliners were being paid, however many portions of halušky or hombergs they did or didn’t shift.

But beyond the mundane and the revelatory there was astonishing, undiscovered (to us at least) beauty. Obviously there were the cities: Budapest’s suppressed imperial grandeur, faded but still apparent; Prague’s hills and alleys evocative in the November mist. Elsewhere we witnessed Lake Balaton fringed with winter’s first snow and in Slovakia the magnificence of the Tatra mountains, the Váh river and the Bystra valley.

And it was in Slovakia that we discovered one of Europe’s most spectacular train journeys. Virtually unknown in the west, it crosses viaducts and passes through tunnels for almost two hours as it winds its way from Margecany through the forest to Červená Skala, climbing 875 metres through the Carpathian mountains, teetering on the edge of precipitous corners and rattling through dense forests.

At the peak a tiny station café sold us smoked ham and bean fazulovika soup and hunters sat behind foaming beer mugs with rabbits dangling from belts and game birds hanging from poles outside. We were the only non-locals on the train and in the café. One imagined that little had changed in that part of Slovakia for decades – even the stations had no signs because they were used only by people who knew them.

Food was abundant, western mythology had led us to believe it might not be. Other than out-of-date tins on supermarket shelves, quantities were similar to the west and little differed, other than a total lack of variety (shelves in Britain this autumn have looked barer). Hungary we learned had a rich, varied cuisine – we were told numerous times how well the nation performed in the quadrennial Culinary Olympics. Their status was well deserved – paprika, game, cheese, salami and sour cream all played major roles, and then there was the wine.

Tokaji had maintained its reputation as one of the greatest wines on the planet, even through the post-war communist era. Produced and venerated like Sauternes – “noble rot” consumes the grapes, increasing their sweetness to provide a complex golden wine. Before the Russian revolution tsars had an office in the region to ensure the best bottles went to St Petersburg.

But Hungarian red wine was excellent too. Near Eger, site of the Ottoman empire’s most northerly minaret, lies the esoterically named Valley of the Beautiful Women. Egri Bikaver – or Bull’s Blood wine – is matured in caves set into the valley walls. Thirty years ago the autumnal smell of woodsmoke from fires heating the caves layered the foot of the valley and we wandered between producers sampling the wine for 2 or 3 pence a glass.

So cheap were prices, and consumer goods pretty much non-existent, that although we were relatively poor westerners – just £1,600 between us when we set out on our four-month haul – we actually found it difficult to spend the money (we returned with nearly £200). On our first visit to a Slovak supermarket (no basket, no entry) we realised the banknotes we’d been issued before departure were of ludicrously high denominations. The contents of our basket came to the equivalent of 0.6 of a penny and our smallest denomination equalled £60. The supermarket simply couldn’t change it – locals were called in to marvel at our notes, gawping as though we were millionaires which, relatively speaking, I guess we were. It was unpleasantly humbling.

One notable evening in eastern Slovakia we splashed out 25 pence (that’s 12.5p each) on a three-course meal replete with Becherovka, beer and wine, but as a rule we were circumspect knowing that locals rarely afforded themselves such luxuries. And the flip side was that some newly budding entrepreneurs had clearly identified westerners as a target, asking the equivalent of £2 for a bottle of beer in a bar when we realised full well the actual price was a few pence.

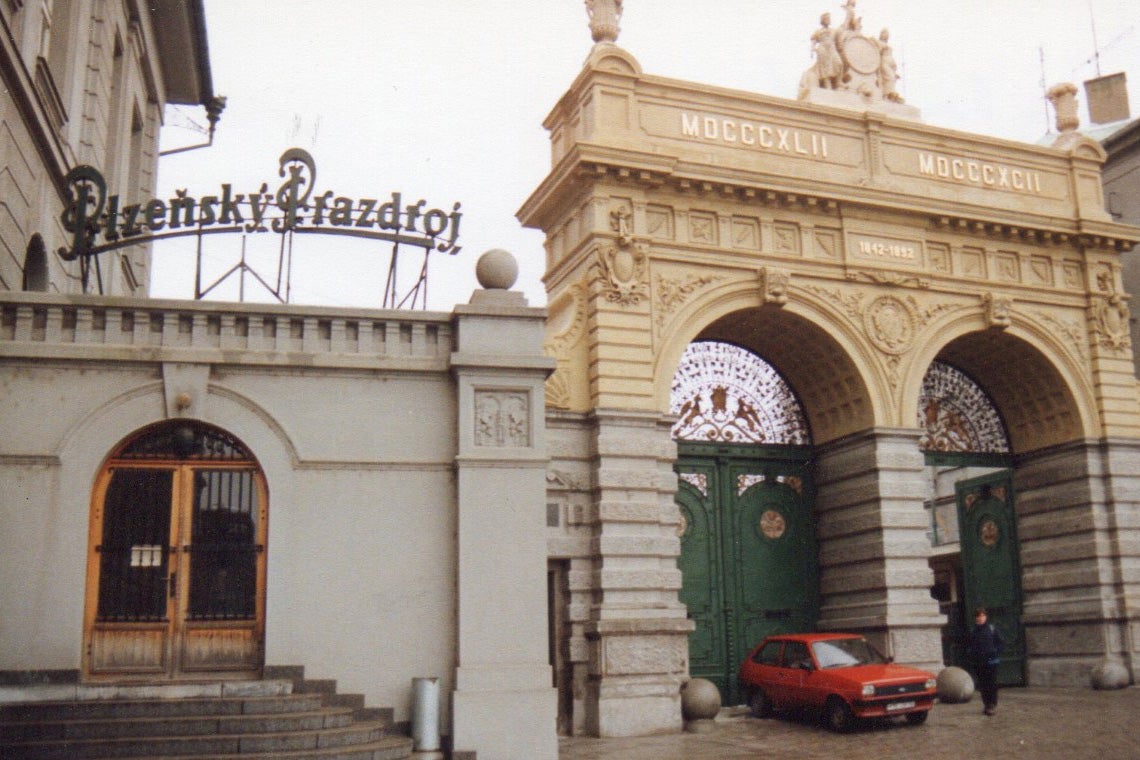

And the beers, in the days before western companies began snaffling up Czech and Slovak breweries for the price of a few grains of malt, were something to behold. Pilsner beer, what the English-speaking world calls lager, was born in the city of Plzeň (Pilsen in German, hence the name) and its finest expressions were found still in a nation whose breweries had pretty much been sealed off from the outside world.

Pilsner Urquell (translates as “pilsner from the original source”) is now world famous as is Staropramen but “efficiencies” in production by new owners mean depth and complexity is not what it was. Deep golden liquorice malt and tangy saaz hops meant that Czech and Slovak beers thirty years ago were very different to their counterparts today. It is said the only thing that stopped the nation revolting before 1989 was that its beers were so good drinkers feared what might happen if capitalism arrived – it seems they were right. In with technology, out with painstaking tradition. Lagering, the process that gives its name to the beer, means leaving it to mature. In the corporate world there’s no time for that. Fortunately Prague’s oldest and most exalted brew pub, U Fleků still exists, although prices have risen accordingly.

But while Hungarian food was rich, flavoursome and plentiful (the term goulash socialism was coined to describe Hungary’s abundant comestible resources), Romanian food hearty and spicy and Czech food stout – always served by waitresses in long, white canvas boots topped with white socks – after a while too much knedliky and sauerkraut saw you longing for a flavour change. In Prague we discovered a single Chinese restaurant serving only four dishes but the queues outside were testament to its piquant drawing power while the pizzas at Mama Rosa’s (a restaurant that still exists) drew similar crowds on the northern slope of Budapest’s Gellért Hill. Pizzerias are two-a-forint now in Hungary, but Mama Rosa’s was exoticism in 1991.

Our journey had highlights aplenty. We caught the last ferry across Lake Balaton before winter set in – heavy waves buffeted our tiny boat as we crossed central Europe’s biggest lake under sleeting skies. As snow fell we visited Tihany, the historical village central to both the legend and reality of the Hungarian nation. Its Benedictine Abbey’s charter is the first extant document written in Hungarian. At the other end of the cultural scale we witnessed the first shipment of Bitburger beer from Germany arriving in Balatonfüred (there were queues despite it costing thrice the price of decent local beer – the power of marketing already taking hold).

We visited Budapest’s famed thermal baths. I was with the toilet-eschewing American and – after passing through the changing rooms we were handed a small handkerchief on ribbons. We couldn’t figure out which part of us it should cover and I had to lead Andy by the hand to each of the baths because he was so short-sighted and his glasses steamed up. Fortunately, we’d inadvertently chosen a bath popular with Budapest’s discreet gay community, so two almost naked men holding hands in a Budapest thermal bath caused no consternation. Sally, meanwhile, whom we’d expected to meet after changing, was in the women-only section first being pummelled physically by a masseuse and then pummelled verbally for not having brought her a tip. “I didn’t know the phrase for ‘I didn’t know’,” she argued plaintively afterwards. We also didn’t know how to get haircuts. There is no real way of expressing your wishes, every language has complex haircut jargon (doubly so if you are a woman, as Sally curtly pointed out).

We did, however, learn the Hungarian words for “50 days”. It’s “ötven nap” and we remember it today. We arrived in summer but knew we were staying into winter so took warm clothes with us that we didn’t wish to lug around until they were required. So we had to leave a bag in left luggage at Budapest’s Keleti station for 50 days. The staff understood and it was there on our return. We also learnt that if you wanted to catch a bus in Hungary you should never pronounce it like you would in English. “Bus” in Hungarian means fuck. Pronounce it “boozs” to avoid startled looks.

Conversely, there were, of course, lowlights including ubiquitous individuals constantly offering to change western currency for a better rate than the bureaus if only you’d pop down this side alley out of view of the cops. And there was the single night we spent in a hotel in northern Romania. Naively we failed to consider why rooms could be booked by the hour, still failed to comprehend when we discovered our room was painted bright red with pink strip lighting and a waterproof sheet under the leopard skin duvet, although we eventually cottoned on as the, erm, comings and goings kept us awake all night.

And although I’m an atheist what the communist government had done to Bratislava’s St Martin’s cathedral was sheer hooliganism. The thunderous dual carriageway leading to the Most SNP (or Bridge of the Slovak National Uprising) – a modernist suspension bridge with what seems like Starship Enterprise attached to one tower – had been rammed through 10 metres from the cathedral’s front doors, also sweeping away the city’s ancient Jewish quarter. Aside from the aesthetic abomination, traffic had damaged the cathedral’s foundations. There are better ways of getting a point across.

The bridge itself was named after the rebellion of 1944 which saw Slovaks rise against their Nazi puppet government in a valiant but ultimately doomed attempt to overthrow their oppressors. Support from the western allies and the Red Army never materialised and what began as courageous insurgency petered out into heroic martyrdom. The postwar communist authorities were nonetheless perpetually keen to promote the heroism of those who fought Nazism and the Museum of the SNP was a major tourist attraction in the town of Banská Bystrica. A concrete structure, like nothing more than a huge mushroom split down the middle, was where we met tour guide Oto. While proud of his countryfolk’s resistance, Oto was more interested in acquiring CDs – he’d managed to get hold of REM’s Out of Time album in the days before western music was legally on sale behind the Iron Curtain and described it as his greatest treasure. He later took us hiking in the mountains and drinking in Banska Bystrica’s bars and we remain friends today even though he would later move to the US.

We were unable to visit Poland and I’m disappointed we chose not to visit East Germany. In later years I have been many times, fascinated by the Berlin Wall

Oto, like so many Czechs and Slovaks was very serious – at first we ignorantly put it down to having lived under an oppressive regime, before it dawned on us that they are instead a pleasingly undemonstrative nation, wonderfully friendly and helpful beneath the laconic exterior. His was not the only lifelong friendship we made. Serendipity intervened on our return journey from Červená Skala to Košice early on in our trip. Walking through the train, my passport fell from my pocket and a man said “careful” in English. Our clothes and possessions, especially our cameras which we hid as much as possible – not from fear of theft but of looking opulent – marked us out. The man, Andrej, and his partner, Silvia, were English teachers. Two years previously they had taught Russian until the state decided otherwise. Later in our trip we stayed with them in the medieval town of Ružomberok surrounded by the Tatras.

We were unable to visit Poland and I’m disappointed we chose not to visit East Germany. In later years I have been many times, fascinated by the Berlin Wall, Thuringia sausages and the Trabant, but we managed to travel through Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania and the length of what was still Yugoslavia on a brief sojourn to Greece. Home Office advice was not to stay in Yugoslavia. The Balkans conflict was kicking off and as a consequence we also couldn’t make our side visit to Bulgaria. I have the visa still. As it was, our train left Thessaloniki for Budapest via Belgrade with just four passengers: me, Sally, a Swedish chap with whom we shared beer, and a shady looking character who we decided was an arms dealer. He locked himself in his compartment and we retaliated by not letting him join in our three-person card school.

We barely picked anybody up until Belgrade at which point we were joined by a hoard of Hungarian shoppers. Apparently Belgrade was cheaper than Budapest and they carried bags stuffed with anything from palinka to potatoes and bed linen to microwaves. As we approached the Hungarian border a few asked if we’d pretend some of the bags were ours. Obviously wary, we refused, at which point one woman said “clever these English” and gave us a bottle of plum brandy. Because the customs checks were conducted in Hungarian we are still unsure whether we became part of the scam (otherwise why the brandy?), although fortuitously we weren’t arrested, despite the bottle poking out of Sally’s handbag.

Our presence at borders often caused consternation. We learned that a bus carrying early-morning workers from Ózd in Hungary across the Slovak border would make our trip to Zvolen a little easier, rather than taking the longer, more obvious rail crossing. So up we turned at 5am at Ózd station to catch the service bus taking Hungarians to a factory just across the border. We were told there would just be a cursory check, but all hell let loose when it became known two British citizens were aboard. Everybody at the border post came to look at us. Then our passports were taken for 20 minutes, and, to our relief, returned. The head guard explained the excitement: we were the first British to cross the border there and then he asked if we’d hold our passports up so we could be photographed alongside him. Maybe our picture still hangs in his front room. Meanwhile a lot of agitated passengers were getting late for work.

At least it was a border we crossed successfully. We stayed in Brno and had hoped to see England play a European Championship football qualifier in Poznań, Poland. As far as we were concerned our visas were in order (and we’d arranged match tickets before we left) but at the crossing point near Náchod, we were denied entry. We have no idea why, maybe the reputation of English football supporters had gone before us and it looked like we were sneaking into Poland through an obscure route, although we really didn’t look the part. But we were stuck. It was November and it seemed we were going to have to sleep in the chilly border hut but a coach travelling back to Brno picked us up. Well past midnight, we heard on the BBC World Service that England had snatched the draw to qualify for the 1992 finals in Sweden.

These days were, of course, pre-internet and pretty much pre-mobile phone. We didn’t have one at any rate. Our sole means of contact with the UK was a phone call if a city had a big enough telephone exchange or grabbing a look at an English-language newspaper in one of the bigger hotels. The World Service was now allowed to broadcast into eastern Europe but reception was sporadic.

We took in quite a bit of football (and a lot of ice hockey in Czechoslovakia). Tickets, for us, were incredibly cheap and we befriended the husband of a woman who offered us lodgings in Budapest. Touts hung around mainline train stations offering space in their houses, realising they now needed to earn hard cash to survive once the free market had rolled into town. The husband had been a Honved fan but hadn’t been for years. When we told him we were interested in going to a game his interest was revived. Miklós took us to perhaps five matches – the flasks of alcohol-laced tea he brought also endeared him to us – including a European tie against Italian powerhouses Sampdoria which Honved won 3-1 despite having their goalkeeper sent off. It was such a big deal the entire match is still to be found on YouTube.

But talk of personal threats would be to offer a negative note. The overwhelming majority of people in whatever country we travelled through were welcoming and friendly

Sadly, Hungary’s issues with football hooliganism were already taking root – we saw terrible clashes with innocent passers-by ¬at a Ferencvaros match and the kind of casual racism still found in some eastern European societies manifested itself at football and beyond. Any player with even slightly darker skin was catcalled cigány (or gypsy). Although it wasn’t ubiquitous – many people we met wanted a more integrated society - it was clear that the Roma community itself, beyond football stadiums, was vilified, ostracised and scapegoated.

One drizzly afternoon on Gellért Hill we found a young woman from New Zealand being comforted by a man. She had been robbed at gunpoint. I went to a nearby café to ask them to call the police – immediately the café staff said “gypsies” were responsible. Then the police arrived and said similar despite the young woman insisting her attackers were white Hungarians. She was even shown photographs of “obvious” candidates they intended to round up. It was frustrating and distressing on many levels.

Apart from the scenes at Ferencvaros we really only had one brush with potential personal violence, at a beer festival in Bardejov near the Russian border in northeast Slovakia. All we could figure out was that a few drunken youths had heard some English people were there and fancied confronting us. Sally later said I’d diffused the situation with aplomb but she clearly had no idea how ad hoc my efforts were and how terrified I was. As they shouted, gesticulated, belched and surrounded us it appears I continued to smile and kept pointing at the beer stalls until they realised I was offering to buy them more. It cost us, but we made it back to the train safely.

We were also advised not to mention Nicolae Ceaușescu while in Romania – apparently he still had widespread support in some regions. But it was impossible because everybody raised the recently executed despot’s reign at every opportunity, keen to tell us how different their nation was now. We met nobody who admitted to being a supporter. Indeed, more than once we were invited to toast his death with any alcohol that came to hand.

But talk of personal threats would be to offer a negative note. The overwhelming majority of people in whatever country we travelled through were welcoming and friendly, genuinely interested to meet westerners. Hungarians especially were proud of their cities, their culture and cuisine, Romanians rarely failed to offer you a glass of wine or fiery spirits just for saying hello, and the Czechoslovaks liked nothing better than to talk history over beer, especially the 1938 Munich Agreement and Neville Chamberlain’s betrayal of their nation at the hands of Adolf Hitler. We got used to saying we weren’t born then. And people on both sides of the Romania/Hungary border wanted to lecture us on the 1920 Treaty of Trianon. Certainly it was enlightening to discover the cultural depth of the Hungarian minority in Romania (and of the smaller but still sizable one in Slovakia).

Later we would visit our friends from the Kosice train as we passed back through Slovakia on our return home. We had to call the only phone in their village (at their school). Many, if most, homes had no phone line and we discussed with them on long evenings over beer and halušky how things might change. Andrej insisted his market town would never have an ATM, he couldn’t see its purpose (it had as many as five next time we returned). He also couldn’t figure out why if you had money you just didn’t spend it. We explained about how, living in a free-market economy, you’d need to save for the future if you possibly could because the state would not necessarily provide. You’d need a home and everything to fill it, a pension or savings, and insurance against calamities if you were lucky enough to be able to…

Silvia lamented that bread was no longer two crowns it was three and how could this be? It had always been two crowns since her childhood because, well, that was the price of bread. We weren’t economists but we tried to explain about inflation and profit. (And it seemed irrational trying to do so). Would Václav Havel make a good president they asked? We didn’t know, we replied. However popular democratically elected politicians are at the start of their tenure, all at some point will be replaced. Now Slovaks treat their politicians as we treat ours, with a healthy dose of scepticism. We are still in touch with Andrej and Silvia, despite a scandal in the town when the latter ran off with a French anti-vaxxer recently. Even indiscretion has been imported from the West.

The two also provided us with perhaps one of the more momentous days of our trip. They knew an official who worked at the local hydroelectric dam high in the Tatras. We were taken inside its control room – a huge, cavernous room reminiscent of mission control in Baikonur and painted Soviet utility pale green. Nothing was digitised, there were no computers – dials and gauges and ticker tape recorded everything. And down we went into the heart of the dam through tunnels between huge turbines howling at the other side of two metres of concrete. The walls glistened and we watched as operatives used rulers to measure gaps between metal pointers set in the concrete – a daily ritual to ensure nothing was shifting. Breathtaking may be an overused and misused adjective but this truly was, made doubly so by being probably the first westerners to visit.

When we boarded the plane to Salzburg we had next to no idea what to expect. We both now admit to being quite nervous. What we found was a dichotomy. Luxuries were few and far between and the state had controlled the lives and actions of its citizens to the point of paranoia and beyond. Energy at times was scarce and electricity outages were relatively common. On visits to provincial museums notably, an old woman (it was always an old woman, usually with a headscarf) would follow you from room to room switching on the light as you entered and off as you left. But poverty was not abject, it was only relative to the west. There was hardship in the sense that life was a daily grind, but begging or destitution, even in big cities, was mostly absent. Infrastructure and the built environment was generally intact, much of it in need of a lick of paint with the walls needing some serious pointing – cutesy tourist fridge magnets weren’t really a thing – but the primary function of buildings wasn’t to look nice.

Trains, buses and trams were old but serviceable and ran pretty much on time – more timetabled around workers’ needs than visitors – and were sometimes rackety and uncomfortable, but they got you to where you were going. And everybody should visit Budapest for the Metro system alone – mainland Europe’s oldest (if you could bottle the smell… simply wonderful). But for most people lives were pretty normal – everybody had an education, everybody had a job, everybody had healthcare, everybody had a home (and did I mention the great beer?). Personal possessions were generally restricted to the necessities of everyday life. Flamboyance and extravagance were welcomingly non-existent.

Pessimism and optimism were equally rampant, split generally although not exclusively on age lines

On balance, I know for certain which side of the Iron Curtain I would have preferred to have lived. Personal freedom alone is worth more than its intrinsic monetary value, however profligate we may be in the west. And some differences we encountered were stark – limited access to phones, cars (there were waiting lists) and everyday things like kitchenware and furniture being some of the most obvious impediments to life as lived in the west. Shops in small towns sometimes had little choice on their shelves and Silvia warned us that if you wanted a specific item you’d be told you “we haven’t got it and we won’t be getting it”. And it would be dishonest to not mention that restaurant service, certainly outside city centres, was surly at best, a truism acknowledged by the natives themselves. “If you don’t like it, don’t eat it,” was a common refrain, Oto informed us.

So yes, things were noticeably different in the east. If you’d been plonked down in the middle of Bratislava in 1991 you’d have realised immediately you were somewhere far removed from London (or Leeds, or Toulouse, or Hamburg). It’s not a cliché to say there was a general drabness about the buildings; there were lots of Stalinist concrete blocks but even the slightly grand older buildings in the style of Mitteleuropa were noticeably unkempt, roads needed tending, clothes were obviously less modish. But the “misery” that maybe we had been led to believe pervaded that half of our continent wasn’t there. If it ever existed, which is doubtful, maybe it had been replaced somewhat by stoicism, a sense that life’s opportunities had differed thus far. But while for certain unfortunate groups their lives had been curtailed under the gaze of the state, the majority of people were like you and me. Just keeping on.

And the personal legacy? I can’t speak for Sally but it has left me with a lifelong fascination with eastern European politics and the repercussions and aftermath of the Cold War, hence the many features I have written on the passing of that era for The Independent. With all that has happened since the original architects of revolution such as Havel and Lech Wałęsa fell from grace – Viktor Orbán’s nativism in Hungary, former Czech prime minister Andrej Babiš’s crude anti-immigrant stance, the pugnacious Euroscepticism of the Law and Justice party in Poland – hindsight perhaps predicted their inevitability. Certainly what are sometimes termed “traditional values” ran deep and other than indigenous ethnic minorities it was rare to see a non-white European.

That said, socialism had induced what perhaps partially evolved into the liberal left, and although it’s been pretty much routed this century it is now rallying against the forces of Fidesz and their like. Babiš was defeated in the Czech general election (although the current presidential crisis is maybe offering him a route back) and Orbán is under threat from a more moderate right-winger Péter Márki-Zay in forthcoming elections. Meanwhile protests continue in Poland against Law and Justice’s anti-EU rhetoric. It’s a cause for hope which simultaneously makes me feel less guilty for developing my passion (undimmed by any reservations expressed earlier about the omnipresence of dishes) for the cuisines of Hungary, and of the Czechs and Slovaks. Who could predict that the ultimate Slovak comfort food halušky, a simple dish of grated potatoes, cheese and crispy bacon could so enrapture me – I cook it with Silvia every time she visits.

And despite the boorish and sometimes violent nature of some of their supporters (who in any case should not be allowed to hijack something that belongs to all citizens not just their unpleasant political clan) I closely follow the fortunes of the national football teams of Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic. We were at Wembley in 1996 to see the Czechs lose the European Championship final to Germany.

Then there is architecture, notably the brutalist Soviet style, its associated statuary and sculpture, and socialist realist art… For all its propaganda, and its unintended ironic resemblance to its contemporary in fascist Germany – it defines an era in a way more tangible than its equivalent in film and photography. But there were other echoes of the past. I was mesmerised by the huge mansions once presumably owned by wealthy families which lined the waterfront at Balaton. All were now divided into apartments but their size and scale, with huge doorways, tall windows, turrets and overgrown gardens, offered a glimpse of what preceded socialism.

We had no idea what we would find when we sat down to plan our trip. But had we thought more deeply, we should have realised. People, their families and friends just getting by, behaving in the ways all humans behave, good and bad. And they were a people suddenly finding a new path and asking us all manner of questions about things of which they had no knowledge or experience: about credit cards, political parties, monarchy, fast food… and ballpoint pens, always ballpoint pens.

Pessimism and optimism were equally rampant, split generally although not exclusively on age lines. We did attempt to explain the benefits of our lives in the west, but also the pragmatism required because an existence based on how much – or how much you don’t – earn can be a precarious one. And they were wise to fear the future – the transition to free market economics was not as painful in eastern Europe as maybe it was the USSR but there would be pain nonetheless.

Yet it genuinely was the trip of our lifetimes, it’s something that nobody today can undertake – not least because Brexit doesn’t allow Britons to stay so long – and we still talk about it pretty much weekly. We didn’t care about anything too much on that trip because this was a whole gigantic exotic world. A tropical island it was not, but exoticism exists in many forms and in unlikely places. There’s exotic in the sense of unusual, fascinating, remote and bewitching. It offered us a brief appreciation of a life lived most Britons of my age will never experience. And none of us will, ever again. We can’t. Because it’s gone forever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks