Buried treasure: How four teenagers stumbled upon the Lascaux cave paintings

A chance discovery by French schoolboys 80 years ago led to one of the most significant archaeological finds in the world. David Barnett tells the astonishing tale of a window opening into prehistoric society

The story of the discovery of the prehistoric cave paintings in Lascaux, in the Dordogne region of southwest France, is one worthy of a Boys’ Own adventure ripping yarn. On 12 September 1940, Marcel Ravidat, aged 18, was walking his dog Robot in the hills outside the town of Montignac. Robot, scampering along the hillside, suddenly disappeared from view.

Marcel ran over to where his dog had last been seen and discovered he had fallen down a hidden hole, and was lost from view. The teenager ran back to the town to gather his three friends, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas, and together they effected a rescue of the stricken Robot.

They climbed down a 50ft-long shaft, shuffling through on their elbows in some cases. Excitement was growing among the four; there were long-standing rumours about the tunnels that crisscrossed the area, and that one of them led to buried treasure.

And, in a way, they did find treasure. Just not the sort they were expecting. Their torches showed that the tunnel opened up into a large cave, the beginning of a network. And adorning the walls was artwork that had possibly not been seen by human eyes for thousands of years.

The four had unwittingly made the archaeological discovery of the century.

It’s a fabulous little tale, even if some of the details are sketchy. For example, some versions doubt there was a dog at all, and that Marcel discovered the shaft a couple of days earlier then went back on the 12th with his friends to investigate. But if there was ever a movie of this story — which there should be, because it gets better — then you’d hope Robot would feature highly.

But it’s not really about the dog. It’s about the bulls, and the horses, and the oxen, and stags. The animals that covered the cave walls. And, of course, the people. Because the paintings gave a rare insight into life at a time that could barely be conceived of. They have been dated to around 15,000BC, but subsequent testing suggested that several “galleries” in the cave system could have been painted over the course of many, many years.

If the thought of a lost dog tugging at the heartstrings isn’t enough for this movie, how about a bit of comedy? The four boys went with their discovery to their schoolteacher, Léon Laval, who was also a member of a local prehistory society.

At first he refused to go with them… he thought it was a schoolboy prank to get him down the hole and trap him there. But he was persuaded and immediately recognised the paintings for what they were.

The teacher realised the significance of the site and was worried that once word got out it would attract more attention and possibly damage and even vandalism. So plucky Jacques Marsal, aged just 14 and the youngest of the group, asked his parents if he could pitch a tent by the entrance to the cave to guard it against too much casual interest.

Léon Laval’s fears about damage to the paintings were eventually realised, though not through wilful vandalism as he had worried about. Simply the sheer number of people wanting to see them

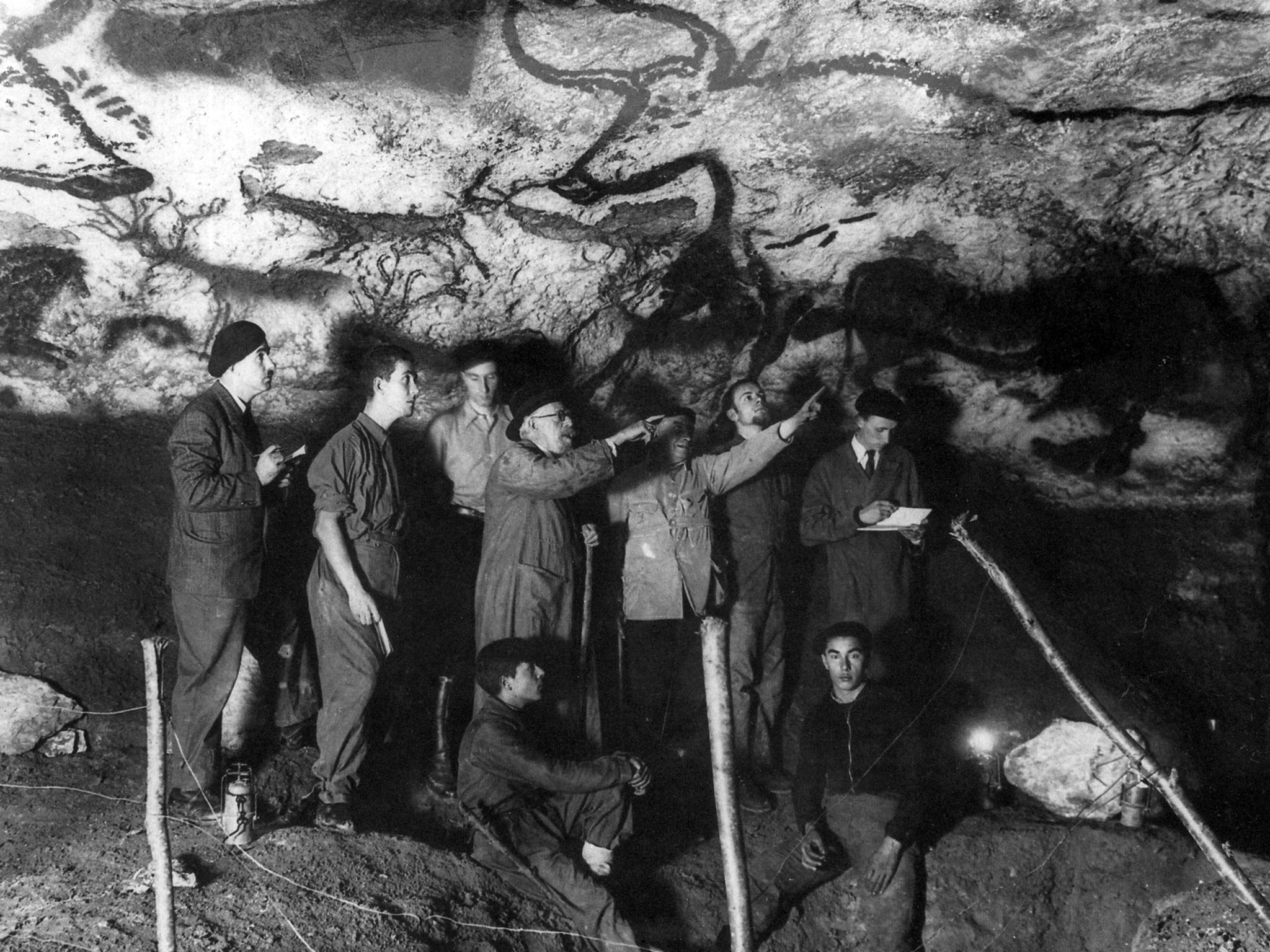

Experts came to verify the paintings and news of the cave slowly began to spread. This was at the beginning of the Second World War, though, and Europe had other things on its mind than archaeological discoveries, as significant as they were.

It wasn’t really until after the war, in 1948, when the family that owned the land opened it up to the public, that their fame really began to spread. People came in their droves to view the paintings, which included scenes of hunting and even a bird-headed man, thought to be a tribal shaman in a head-dress.

Léon Laval’s fears about damage to the paintings was eventually realised, though not through wilful vandalism as he had worried about. Simply the sheer number of people wanting to see them. Condensation formed on the walls from the mere breath of so many visitors, and the bright lighting set up to illuminate the paintings caused them to fade considerably.

So in 1963 the Lascaux cave system was closed to the public, apart from scholars and academics who wanted to study it. In 1979 it was designated a Unesco World Heritage Site. However, its story did not end there.

Twenty years after it closed to the public, the cave opened again… sort of. A series of perfect facsimiles were created and the paintings laboriously and painstakingly copied using materials the original artists might have used, including charcoal and ochre, to allow visitors to see them in their natural splendour.

There have actually been three reproduction sites created since 1983. The first one, which copied the paintings in what had become known as the Great Hall of the Bulls, the first cave the boys discovered, and it was initially displayed at the Grand Palais in Paris before being located about 200 miles away from the original cave.

What then became known as Lascaux III was a series of reproductions of the other caves, or galleries, which for the past eight years have been on tour around the world. And Lascaux IV, which opened in 2016, is the latest bid to produce the Lascaux experience, housed in a museum overlooking Montignac.

Despite these measures, though, the paintings continue to be at risk. According to the Bradshaw Foundation, a nonprofit organisation devoted to cataloguing and preserving rock formations and art, the Lascaux cave is in a dire predicament.

Luiz Oosterbeek, secretary general of IUPPS (International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences), writing for the Bradshaw Foundation, warned: “These hauntingly beautiful prehistoric cave paintings are in peril. Recently, in Paris, over 200 archaeologists, anthropologists and other scientists gathered for an unprecedented symposium to discuss the plight of the priceless treasures of Lascaux, and to find a solution to preserve them for the future.

“Since the year 2000, Lascaux has been beset with a fungus, variously blamed on a new air conditioning system that was installed in the caves, the use of high-powered lights, and the presence of too many visitors. As of 2006, the situation became even graver – the cave saw the growth of black mold. In January 2008, authorities closed the cave for three months, even to scientists and preservationists. A single individual was allowed to enter the cave for 20 minutes once a week to monitor climatic conditions.”

While the paintings and the cave are the backdrop of this story, the real human face of it comes from those four boys who rediscovered them

While conservation work continues to preserve the cave system, its discovery is being honoured, 80 years on. The village of Montignac is this week the focus of the events, which have of course been reduced in capacity because of coronavirus. Today, for the anniversary, a new walking trail will be inaugurated, the three-mile trail following the path taken by the four teenagers who discovered it all those years ago.

There will also be a special tribute to the four themselves, Simon Coencas, Marcel Ravidat, Georges Agniel and Jacques Marsal. Because while the paintings and the cave are the backdrop of this story, the real human face of it comes from those four boys who rediscovered them after so long, and brought them into the light once more.

But what happened to them? Over to the organisers of Lascaux IV for a potted history of what happened to the four in the aftermath of the discovery.

Jacques Marsal, “the Montignacois”, was almost 15 years old that summer. A young pupil on vacation, he was present on the now famous day of 12 September 1940, going to alert his former teacher Léon Laval a few days later. He did not return to school, but camped on the spot with his friend Marcel to ensure the protection of the cave until 1942.

That same year, he was arrested on the Montignac bridge by the French gendarmerie and interned by the Compulsory Work Service in Germany. At the suggestion of Marcel Ravidat, he became the official guide of Lascaux from the opening to the public in 1948, and did this for about 15 years

Georges Agniel was born in 1924. His parents went into exile in Paris to work there. Georges was on vacation with his maternal grandmother when he took part in the fabulous discovery. However, he had to leave his friends very quickly to go back to school and join his parents in Paris.

Technical agent at Citroën then at the Thomson-Houston company, he returned to Montignac on 11 November 1986 to meet his three companions Marcel, Jacques and Simon. He then participated in the ceremonies of the 50th anniversary of the discovery, in the presence of François Mitterrand, and was decorated with the National Order of Merit in 1991. He is the first adult to have entered the Lascaux cave.

Simon Coencas, who died in February 2020, took refuge in Montignac with his Jewish family in 1940 when he took part in this sublime epic. At 13 years old, he is the youngest of the gang. He does not appear in the photographs taken in the days following the discovery: with his family, he returned to Paris a few days. Life was not easy for Simon, who saw his father and mother being arrested, then himself arrested and deported to the Drancy concentration camp.

He miraculously emerged from it one month after his deportation and hid until the end of the war. As he liked to say, “he will do 36 jobs” but was keen to be present every year for the anniversary of the discovery. As with his childhood friends, Simon was decorated with the National Order of Merit in 1991, then was appointed Officer of Arts and Letters in 2011.

Marcel Ravidat, who was the first to discover the cave, continued to work as a guide and official guardian of the cave. When it was closed in 1963 he became a mechanic at a nearby paper mill, and died in Montignac in 1995, aged 72. And an honorary mention for Léon Laval, the teacher who thought the boys were trying to trick him into the cave for a laugh. He worked tirelessly to protect and promote the cave during his lifetime, and was the official “Curator of the Grotto” until 1948, when it was opened to the public.

And what of Robot? Well, not much is known about him, or even if he was there at all when this magnificent window into our prehistoric past was uncovered. A shaggy dog story, perhaps, but it’s nice to think that we owe a dog a debt for this amazing find.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks