Kim Wall’s reporting gave voice to the voiceless

Today would have been Kim Wall’s 34th birthday. What would she be reporting if she were alive? Rebecca Banovic recalls a journalist who left a legacy more valuable than words

Kim Wall’s story, like her writing, is full of compassion, unwavering courage and determination. She lived a life of adventure, travel, rewarding work and brilliant friends. A journalist to her core, Kim was intelligent and formidable. Only in hindsight do we see how mighty her pen was.

“If Kim can act as a role model for other people, that really makes a difference,” Ingrid Wall, Kim’s mother, tells me. “Just seeing the reaction of youngsters, who didn’t even know her, is very touching. They say they want to follow in her footsteps by writing articles and poetry,” says Ingrid smiling, remembering her daughter.

Kim’s story started in Trelleborg in southern Sweden. A pleasant and tight-knit seaside town, known for its many ferry routes, Trelleborg was a comfortable place to grow up.

Read More:

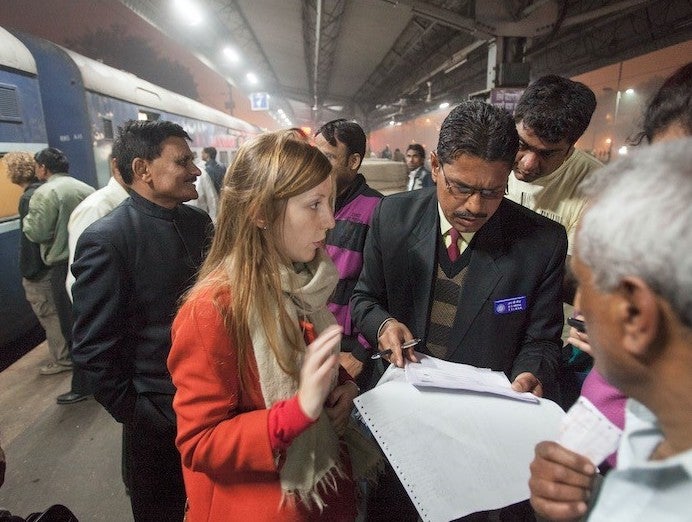

“Trelleborg is a small town,” says Ingrid. “But Kim would always find a story even in the smallest of places. At the height of the refugee crisis, many of the refugees would arrive in Trelleborg by ferry.

“She wanted to speak to them, so she waited for them at the port. Of course, she made a piece about the youngsters she interviewed. She always saw the small person.”

Kim’s mother smiled, remembering her daughter’s kindness and empathy. Since Kim’s passing, Ingrid often gives talks to students in Trelleborg. “We have a responsibility to tell others in this small town that you can have the entire world as your working field,” she says. “The only thing that stops you is yourself and imagination.”

Kim felt a loyalty and love for her hometown, but always yearned for the wider world. She went on to study international relations at the London School of Economics followed by a rigorous masters programme at Columbia University’s School of Journalism – described by many as the “Oxbridge of journalism”.

During her short and bright life, Kim Wall emerged as one of the most promising and ground-breaking journalists in the field. At such a young age Kim’s work was published in many prestigious publications such as the The New York Times, The Atlantic, Vice and TIME, to name a few. Her work looked through the eyes of people as far afield as Cuba, Uganda, and the remotest corners of the Pacific Ocean; she really had a unique ability to connect with a myriad of people. She embraced the life of a roving freelance reporter; a job and a style that, thanks to budget cuts, has almost faded from existence.

She always made the reader think, and so showed her greatest interest and concern: giving voice to the voiceless

In the death of Kim Wall, journalism lost a young woman of decided originality and promise. What work was she most proud of?

“She was proud about her Marshall Islands piece,” her father, Joachim, tells me.

In 2015, Kim wrote about “The Runit Dome” in the Marshall Islands. The US military built a giant concrete dome there to house the radioactive waste from nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s and 60s. It is leaking, and the Marshallese are still campaigning for adequate support. If left unattended, rising sea levels or fierce storms could crack the Dome open, and spill nuclear waste across the region.

“She went with her two friends. It was a tough journey. When she called us, we had to look up where it was. We had no idea how she managed to get to such a remote place,” says Joachim. “It was, and still is, an important piece about what the US are doing,” he continues.

Kim’s work still causes ripples. For her reporting on the Marshall Islands, she received a prestigious German reporting award. The LA Times then took up the story and published a long investigation on the site. Last year, the US department of energy did a report on the status of the dome and concluded the site required no further attention. The Marshall Islands dispute these findings.

Kim’s work constantly shows the power of her persistence, and deep empathy. Her journalism is demanding and requires careful consideration. Kim’s writings appear scattershot in their topics. Yet she always made the reader think, and so showed her greatest interest and concern: giving voice to the voiceless.

Her stories often centred on quiet people and individuals trying to make a living and meaningful existence in a chaotic and changing world. She published on Ugandans navigating a wave of Chinese investments in their country; the clients and businessmen in Cuba’s underground digital markets; and even the Furry subculture.

“Some people may call it naïve, but she wanted to help people in the third world,” says Ingrid. “Like when she went to write about the ‘Women Fighters of the Tamil Tigers’. It’s always the conqueror that writes history and no one speaks about these issues. We just don’t hear about it. She wanted to do the opposite and shine a spotlight on these people.”

The piece Ingrid tells me about is an intimate portrait of the women who fought alongside the Tamil Tigers. In 2016, Kim travelled to what would have been Tamil Eelam and spoke to women about their complex personal histories and what led them to the Tigers.

The story of the Tamil Tiger women became the last piece Kim wrote. It was published posthumously. I tell her parents: “She had great editorial foresight to have known that was a story before it became one.”

They both smile and nod. “Before she died, Kim said the next big problem, or war in the world, would be about water,” says Joachim.

But focusing on the perpetrator brings an opportunity cost – we are diverting our attention from something more worthy: the victims

Joachim’s words ring like a bell. Flashbacks to last year in the newsroom as reports came in about skirmishes between Indian and Chinese forces high in the Himalayas. The two nations had been building up rival projects to exploit the vital water resources of the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra River. The two countries were also on the brink of war over the Pangong Tso lake – a disputed territory. Additional clashes also took place at locations in eastern Ladakh.

“She also said we will start realising the importance of freshwater ecosystems, like in India,” he adds

Around the world, rivers, lakes, and wetlands have increasingly become degraded by dams, pollution, habitat loss, climate change, and the introduction of invasive species. In West Africa and Central America, climate change is already devastating crops, and forcing farmers to flee. But people are taking notice and freshwater issues are becoming a higher priority for conservationists. Hopefully, journalists will follow suit by bringing these issues to light.

We’ve spilt so much ink over Kim Wall; but very little about her. A quick google search of her name returns about 552,000,000 results. Unfortunately, the world does not remember her for journalistic excellence, or touching empathy. In 2017, Kim died while on an interview assignment aboard a homemade submarine. She was murdered by the owner.

“There was enormous publicity surrounding what happened to Kim. There are hundreds and thousands of articles that covered the story, most of them describe Kim as ‘a journalist’ – nothing more. The rest is about the murder and the murderer,” says Joachim.

“It shouldn’t be possible for people to so easily fall into the trap of writing about the crime and perpetrator. We would like people to know who Kim was,” he emphasises.

Journalists must inform the public about crime. But it is a sad reality of the industry that, more often than not, we obsessively zoom in on every minute detail about the perpetrator: their interests, relationship history, education, relatives, pets, medical history – anything that might shed light about them, anything that might provide context to their cruel behaviour.

It has become an appalling habit. But focusing on the perpetrator brings an opportunity cost – we are diverting our attention from something more worthy: the victims, and the lives they lost. In this instance, Kim.

When we do know the victim, it is a vague notion, perhaps even just a shadow of who and what they truly are. A throwaway sentence to establish them, before casting them aside. As journalists we have a choice: we can either wear down the victim or, by contrast, help contribute to their story.

Kim will never write another word, but others can. Ingrid and Joachim want journalists to continue fighting in Kim’s spirit – to arm themselves with their pens and use them in the struggle for democracy and press freedom.

To honour Kim, they created the Kim Wall Memorial Fund, which aims to “fund a female reporter to cover subculture” and what Kim liked to call “the undercurrents of rebellion”.

“We read through the applications and think: ‘This is a typical Kim story,’” says Ingrid smiling.

“Kim can no longer write her stories, so we want someone that can go out in her spirit.”

The fund provides a $5,000 grant to the successful applicants, alongside: insurance, reporting-related costs (including travel), logistics, visa fees and payment for fixers/translators.

“We usually throw a party for the grantees new and previous. Next year, we are throwing one hell of a party for the grantees to make up for it!” Ingrid laughs.

It is important to emphasise that Kim’s fund provides insurance for the grantees. Ingrid and Joachim reiterate it is always better for journalists to go out in a team of two to three. The journalism will be more effective if there is one person writing, another taking photos, and another filming. As news organisations battle with shrinking budgets, placing a story becomes harder, especially for the freelancer who does not have the same protections that staff do. What happened to Kim must never be used to blame a woman for reporting on her own, or to say that women aren’t able to do journalism. What needs to happen is this: editors and newsrooms everywhere must take responsibility for their duty of care – especially over their freelance journalists.

She loved karaoke and we just could not understand why. It was a completely foreign concept to us. She always pulled her friends to go with her

“Kim must be mentioned as a journalist that died while she was doing her job. It wasn’t a random attack. She died doing her job,” emphasises Ingrid. “If women are scared because of what happened to Kim then democracy is the biggest looser. It is extremely important we have more female journalists.”

“Even in Scandinavia, it is not equal. We need more female journalists out in the field,” adds Joachim.

Again, Joachim’s words ring like a bell. Although there has been considerable progress for women working in journalism in the past few decades, women are still noticeably in the minority in the top journalistic roles, despite making up the majority of journalism students. In many countries, the majority of high-profile journalists and editors remain male.

Even the opportunities that are presented to women in the journalistic workforce; much of it is confined to writing about softer topics and areas considered as ‘traditional women’s interests.’ There are still enduring stereotypes; women predominate on the lifestyle pages, but do not feature much in other areas such as war and foreign reporting. Kim was smashing these stereotypes with each article she wrote.

And what was she like, how was Kim beyond her work? Ingrid and Joachim pause, look at each other, and burst out laughing. “She loved karaoke and we just could not understand why. It was a completely foreign concept to us. She always pulled her friends to go with her,” laughs Ingrid.

“She must have picked it up from the English while she was studying here,” I retort

The contagion was immediate. For the majority of the interview, we laughed at Kim anecdotes.

Read More:

“She also wore the craziest Scandinavian sweaters,” Ingrid adds. We fall into a fit of laughter. It’s a beautiful image. A conspicuous and proud Scandinavian dragging her friends to a unique and crazy foreign practice she had embraced. Few countries other than England have the collective popular music culture needed to make such riotous karaoke nights.

Today would have been Kim’s 34th birthday. Thinking about Kim – where she would be today and what she would be reporting on were she alive – brings tears. Yet her legacy is powerful. She wrote with all her might and left a legacy more valuable than words.

Please visit www.rememberingkimwall.com for more updates on the Kim Wall Memorial Fund and information on how to donate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks