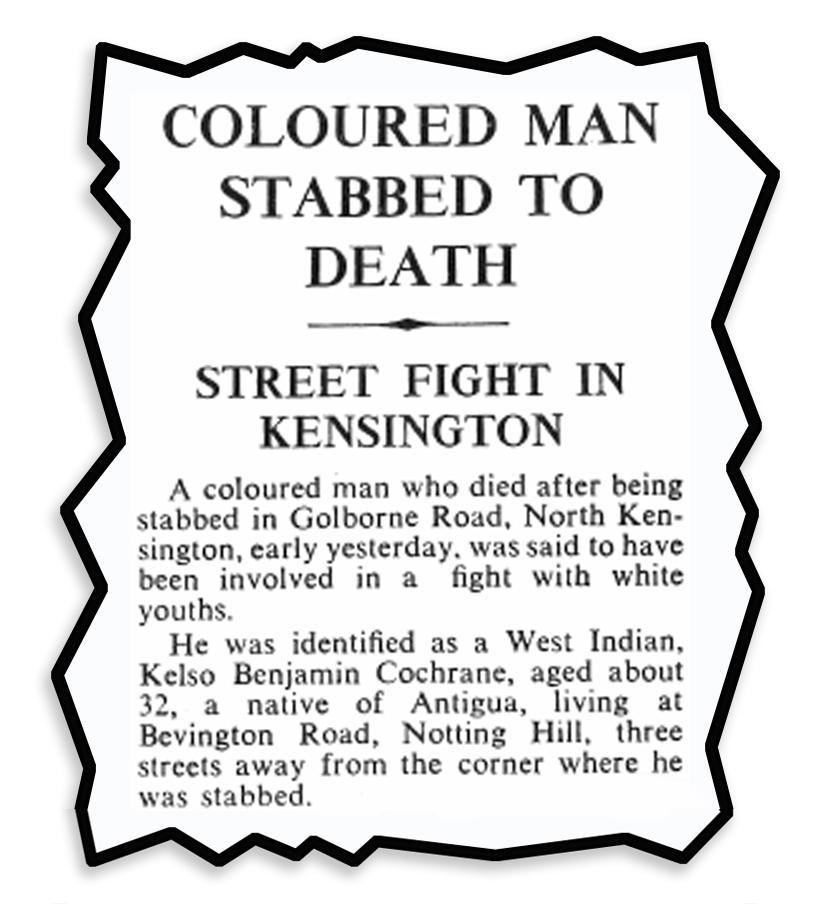

Sixty years on, Kelso Cochrane’s daughter finally finds peace in north Kensington

The murder in May 1959 was a watershed in British race relations. Sixty years later, Mark Olden joins Cochrane’s daughter Josephine as she arrives in London to trace the last steps of the father she never knew

It was early in 2007, and Josephine Cochrane, a social worker in Brooklyn, New York, was having a bad day. “What’s the matter?” her supervisor asked. Josephine told her what was on her mind, something that had troubled her for decades, through years of imprisonment and addiction, and especially now she’d turned her life around.

She’d grown up without her dad, and didn’t know how he’d died. She said that her mother had never given her all the details: “Maybe she knew them, maybe she didn’t.”

“Why don’t you google him?” her supervisor asked. “What’s his name?”

It was on the screen in seconds: the story of the murder that was a watershed in British race relations. Josephine read the article, and started crying.

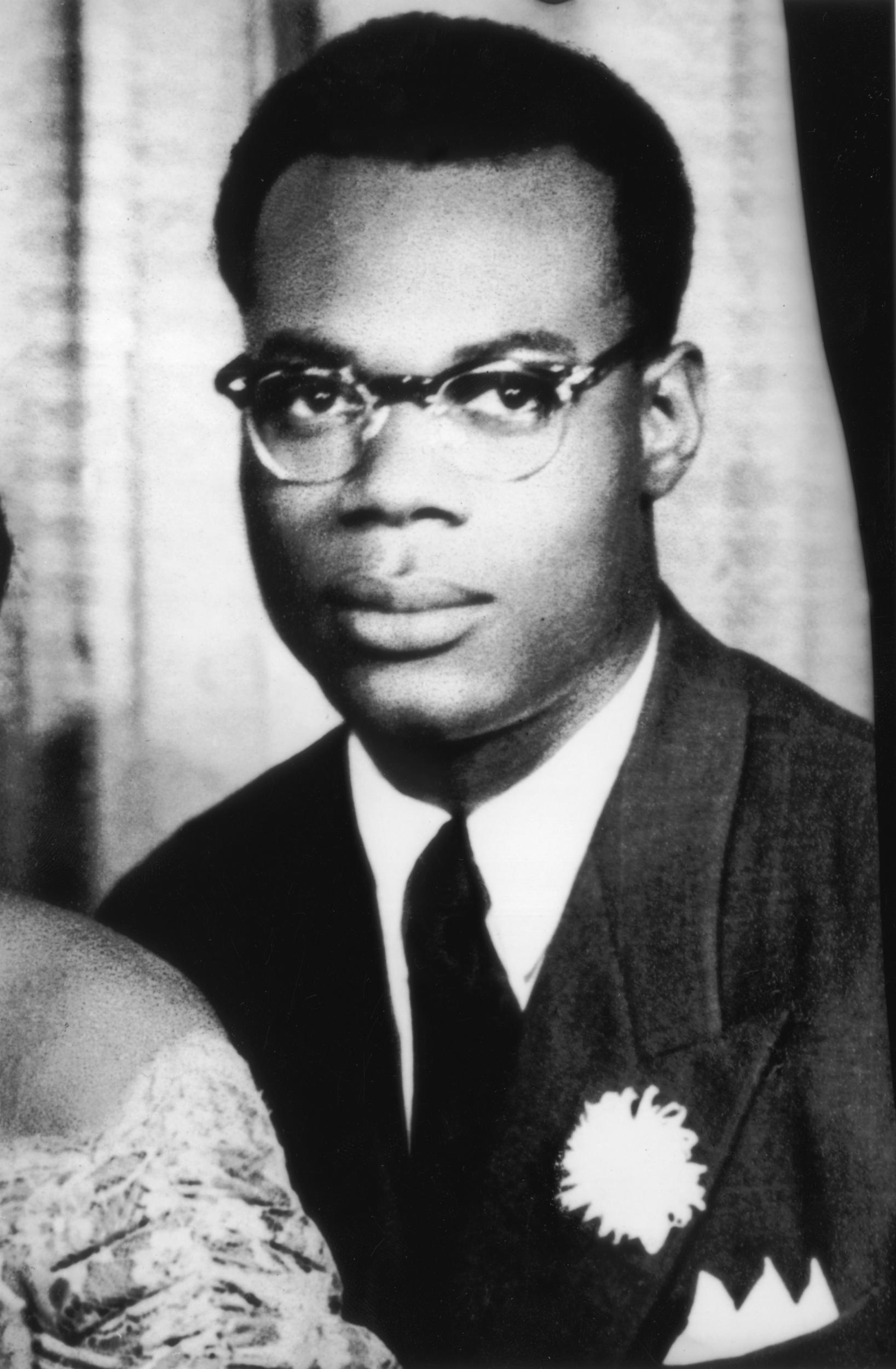

At around midnight on 17 May 1959, Kelso Cochrane, a 32-year old man from Antigua who’d settled in London five years earlier, was a five-minute stroll away from his bedsit in the rundown northern edge of Notting Hill, in North Kensington. He was returning from Paddington General Hospital, where he’d been treated for a thumb he’d broken at work as a carpenter earlier that week.

As he approached the corner of Southam Street and Golborne Road, six white youths closed in. Witnesses described pushing and shoving, as Kelso tried to defend himself. Then the youths ran off. In the melee, one of them had driven a knife into the main chamber of his heart, a blow delivered with unusual force, the coroner said later.

No one was convicted for the crime, despite the killer’s identity being “the worst kept secret in Notting Hill”. But like the death of Stephen Lawrence 34 years later, the murder had a lasting impact.

It came eight months after the Notting Hill race riots, some of the most serious racial violence in Britain of the last century. It also came against the backdrop of intense far-right activity in the area. The previous month, Sir Oswald Mosley, Britain’s wartime fascist leader, had declared that he would stand for parliament in North Kensington in the 1959 general election. At the packed, public meeting marking the announcement, The Times noted that: “Most of the questions addressed to Sir Oswald Mosley concerned aspects of the colour question, and to these he answered emphatically: ‘We are determined they shall go home.’’’

News of the murder and the unease on the streets of Notting Hill spread alarm in the corridors of power, according to declassified documents. The prime minister, Harold Macmillan, convened a special meeting of ministers; Rab Butler, the home secretary, called for witnesses and was considering, a report said, “recruiting coloured police as part of his campaign to end racial tension”. The police – to the incredulity of many – swiftly denied any racial motive to the killing.

Campaigners, meanwhile, rallied to demand justice for Kelso Cochrane and to call for laws banning racial discrimination. Prominent among them was Claudia Jones, the Trinidadian-born communist who’d been deported from America during the McCarthy witch-hunts, and who a few months before, had started the forerunner to the Notting Hill Carnival.

Through the case, Jones, along with the likes of Amy Ashwood Garvey, the ex-wife of Pan Africanist leader Marcus Garvey, helped push anti-racism into the mainstream political agenda: they founded an organisation in response to the murder (the Inter-Racial Friendship Coordinating Council), and organised meetings and protests. Six years later, in 1965 the UK’s first Race Relations Act was finally passed.

Growing up in Harlem, Josephine knew none of this. Following her shock discovery at work in her office in Brooklyn though, we made contact (I’d investigated the case for a 2006 BBC documentary), and I put her in touch with some of her Antiguan relatives.

Finally, last month – on the 60th anniversary of her father’s death and the day before what might have been his 93rd birthday – Josephine left the United States for the first time, and flew to London to retrace her father’s footsteps.

The 66-year-old grandmother who I meet in the arrivals area at Heathrow is tall, as her father was, and ebullient, just as Kelso’s friends have described him. She is also, as I discover over the next three days, an eloquent narrator of her own tumultuous story.

Josephine was born in 1953, two years year after Kelso married her mother Kansas, who’s still alive, who he’d met after moving to the US. However, in February 1954, he was deported to Antigua for overstaying his American visa. Borrowing money for a ticket from his brother Stanley, he made his way to England, where he worked as a carpenter while nurturing hopes of becoming a lawyer. But he wanted to return to the US. In September 1956, he applied for citizenship with his wife’s support.

The following May his request was accepted. But according to documents in the National Archives, Kansas withdrew her backing after meeting another man. Kelso also began a relationship, with a Jamaican trainee nurse called Olivia Ellington. (The writer Zadie Smith’s new book of short stories contains a fictionalised account of Kelso and Olivia’s last days together.)

On 30 May 1959, two weeks after Kelso was murdered, a Daily Chronicle journalist wrote that he’d located Kansas in a New York boarding house, and broke the news of her husband’s death. “Clutching her six-year-old daughter’s [Josephine’s] hand, Mrs Cochrane said: ‘It is such a shock. I read in the papers that someone had died in the Notting Hill troubles. I never thought that it would be Kelso.’”

Over a coffee on a wet, blustery day on the Portobello Road, where her dad had spent some of his final afternoon shopping in the market, Josephine dismisses the report. She has no memories of the incident and says such a quote would never have passed her mother’s lips. She also has no memories of her dad. But she remembers the dolls and the tea set he sent her from England, and the picture of him in uniform, which was on the piano when she was growing up.

“I wanted a father. Everybody else had one. So I wanted to know why mine wasn’t there,” she says. “I used to ask my mother: ‘Did he ever know us?’ She said: ‘Of course. He used to come home in the evening and put you in his lap and rock you to sleep.’”

But when Josephine asked her how he’d died, perhaps to protect her, Kansas clammed up. “My mother didn’t really want to talk about it. She would just say that he was killed in a war, or on some kind of military service.”

When she turned 19, Josephine set out to discover the truth. She approached a veterans’ organisation for details, but to no avail. “They told me there was no war at that time. I said there had to be, because my father died in one.”

After a while, Josephine says, she lost hope, and headed down “the road of self-destruction”. For around 15 years she led a life of crime and drugs: “In and out of prison. In and out of college. Never finishing nothing. Never doing what I’m supposed to do… I became addicted to cocaine and stole for my living. And I got caught quite a few times. Then one day I got tired.”

She’d grown up in the Nation of Islam, but in prison adopted the Sunni faith. “The Nation of Islam was about Malcolm X and Farrakhan and it was more militant, but it taught me my African history. I needed to be more submissive to the Creator. And that’s where jail came in. It took a long time for me to really let go of the negative way I was living, but after two or three times in jail, it finally happened. My mother gave me such a strong foundation of education that I didn’t stay down in the gutter.”

She went back to college and threw herself into her studies. “Sometimes I didn’t have the money for school, so I had to go back to work. Thank God for my mother, because she took my children and made sure they were all right, and my sisters were there to help too.”

It was on a jail programme that she realised how badly she wanted her father, and the sense of abandonment that had seeped in and affected her own relationships. Drugs had helped mask her feelings about her dad, she says. As she emerged from those lost years, the feelings resurfaced. Her trip to London is a way of helping to resolve them.

We walk up Ladbroke Grove to the small brick church where Kelso’s funeral was held 60 years ago. Afterwards, 1,000 people had silently followed his cortège up to Kensal Green cemetery. Three hundred metres away we stop on Bevington Road, where Kelso was living in a bedsit in a freshly painted Victorian terrace that’s since been torn down – before we head the short distance up Golborne Road, and the scene of the murder. As we cross the iron bridge that Kelso stumbled towards after being ambushed, Josephine appears to visibly tense. “Oh my gosh,” she says.

She crosses the road and studies the blue plaque that was unveiled 10 years ago, on the 50th anniversary of his death. It reads: “Kelso Cochrane. Antiguan carpenter was fatally stabbed on this site. His death outraged and unified the community leading to the lasting cosmopolitan tradition in North Kensington.”

That evening, Josephine is in the little library a few metres away for the launch of the Kelso Cochrane Memorial Archive. It’s been initiated by Isis Amlak, one of the local activists who’ve kept her father’s memory alive through the years. For Amlak and others, the way the community came together to demand change in the wake of Kelso’s murder is part of North Kensington’s history of resistance: a history that continues today in the struggle for justice for the victims of the Grenfell fire.

Following music and speeches, the crowd, which includes Antigua’s high commissioner, Karen-Mae Hill, the local MP, Emma Dent Coad, and members of Kelso’s extended family, look on as Josephine addresses them:

“After the dark road, and after my learning experience, I was still on the quest to find my dad... I came here and I wanted to meet all you people who have been holding on to his memory for so long. And I do believe that you have held on to his memory so that I can be the one to receive it.”

The next day, Josephine visits her dad’s grave for the first time; the site where, in 1959, people rushed forward as his coffin was lowered into the earth and hundreds had sung hymns for an hour afterwards, with “deeply emotional emphasis” said The Times. “Black hands clasped white as the mourners quietly dispersed,” the Daily Worker newspaper reported. “The absence of bitterness and the determination of the organised coloured people had made it a deeply moving occasion.”

Yet whatever changes her father’s death heralded, Josephine sees the same issues being played out today in different ways. “Things might have changed on paper. But in the hearts of mankind, it hasn’t changed. We’re doing the same things we did [then]. It’s a mad circle.” She talks of the “mass incarceration” of black men in the US, the deaths of innocent black people at the hands of the police, and her fears for her grandson as he walks the streets.

In Britain, she could have cited the Windrush scandal, the divisions being stoked in white communities by far-right extremists (as detailed in a report this week), or the 93 people who died as a result of racially motivated attacks in the 15 years since the Macpherson Report into Stephen Lawrence’s death was published. But while societies struggle to move on, Josephine appears to have.

“Coming to London is like the closing of a door. I’ve walked in my father’s footsteps. I’ve said goodbye to him. And I want him to know that we never forgot him. We love him,” she says.

Mark Olden is the author of ‘Murder in Notting Hill’, an investigation into Kelso Cochrane’s murder

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments