Is it possible John Lennon killed the ‘fifth Beatle’?

Evidence that a fight with the band’s frontman led to Stuart Sutcliffe’s death by brain haemorrhage is just as muddled today as it was all those years ago, writes David Lister

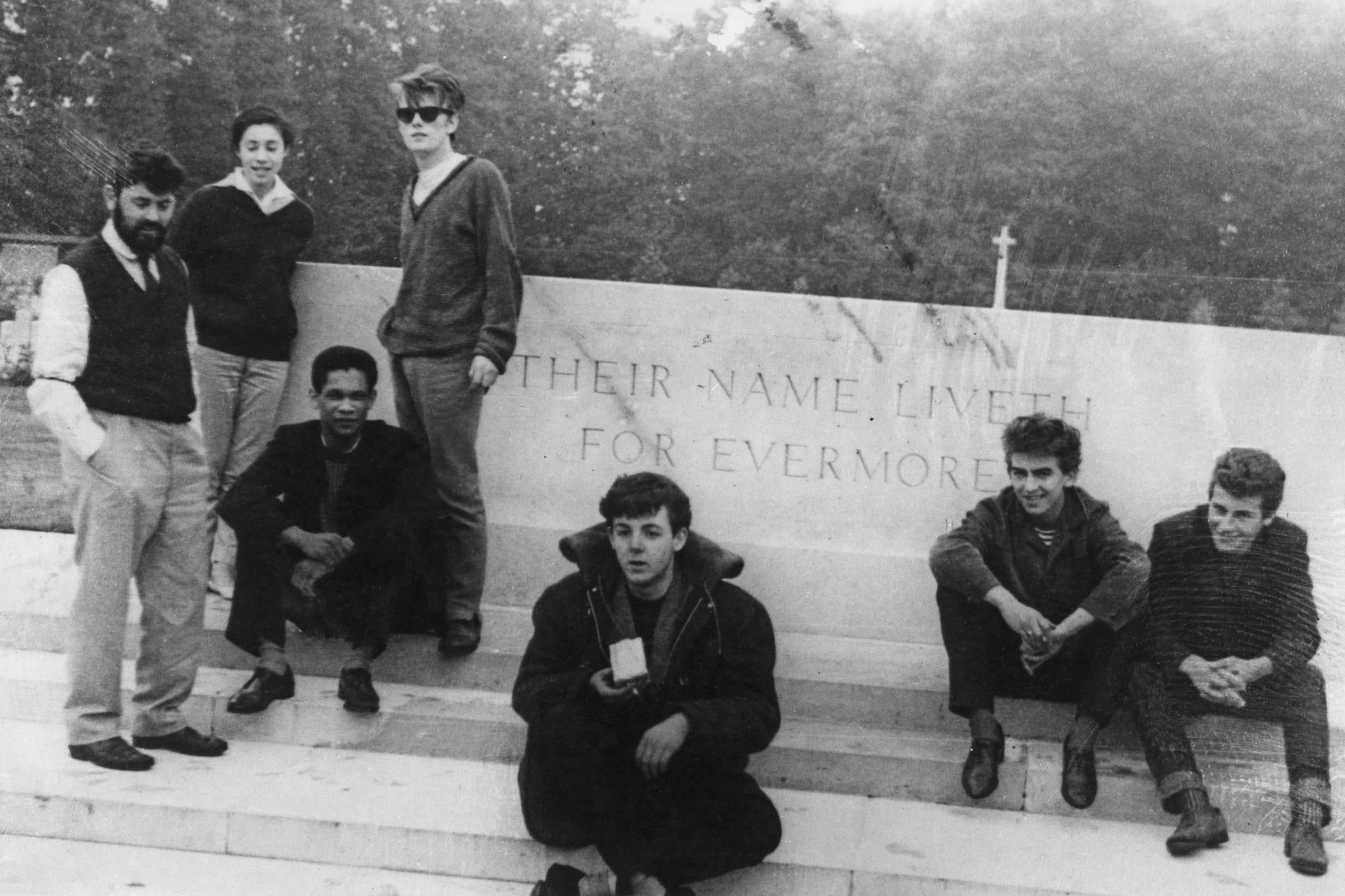

The death of Astrid Kirchherr earlier this summer evoked memories and anecdotes of the early days of The Beatles in Hamburg. The German photographer and friend of the group captured their youth in iconic photos, which became key imagery to the band’s story, and which even now are still regularly posted on social media.

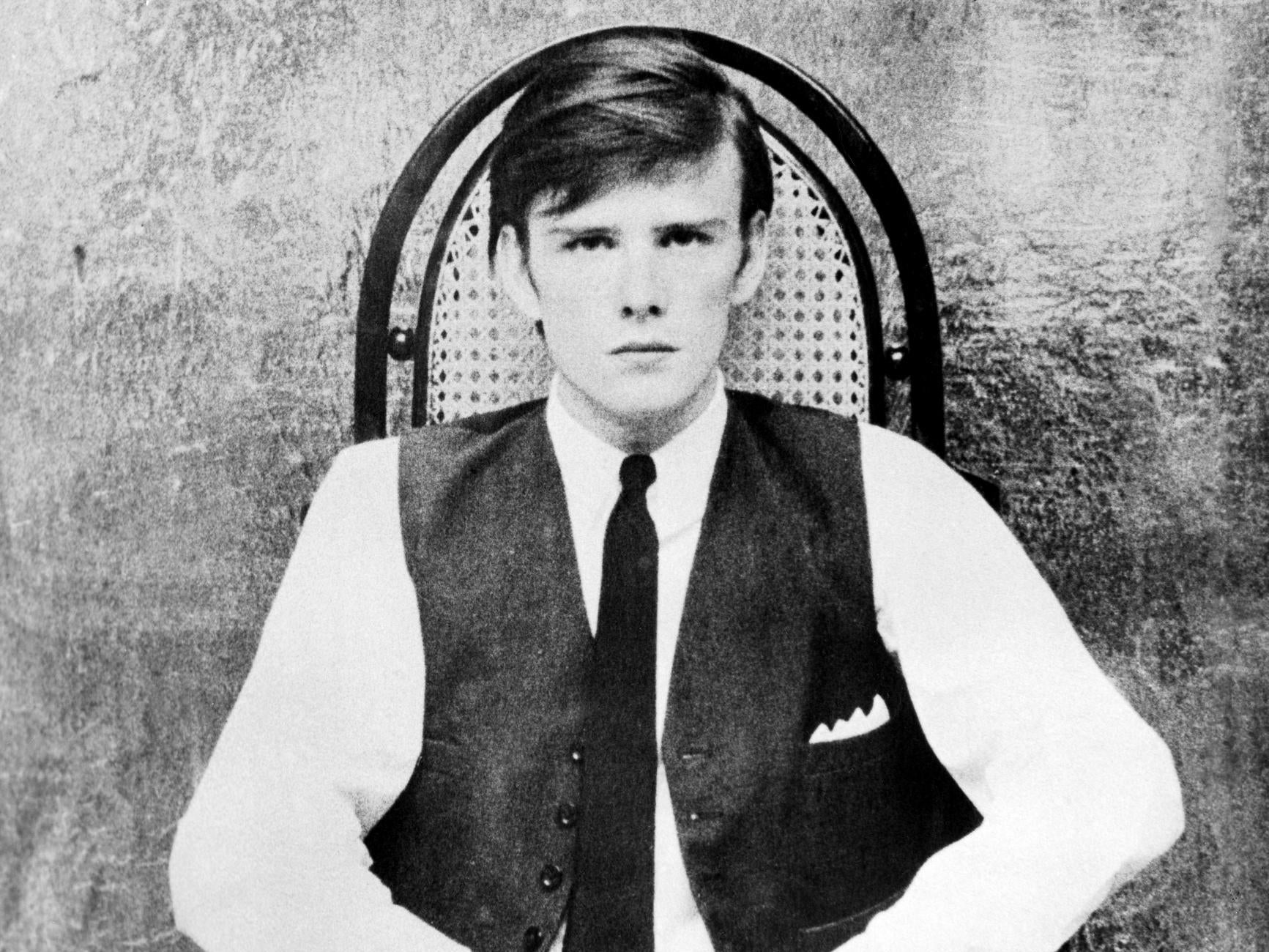

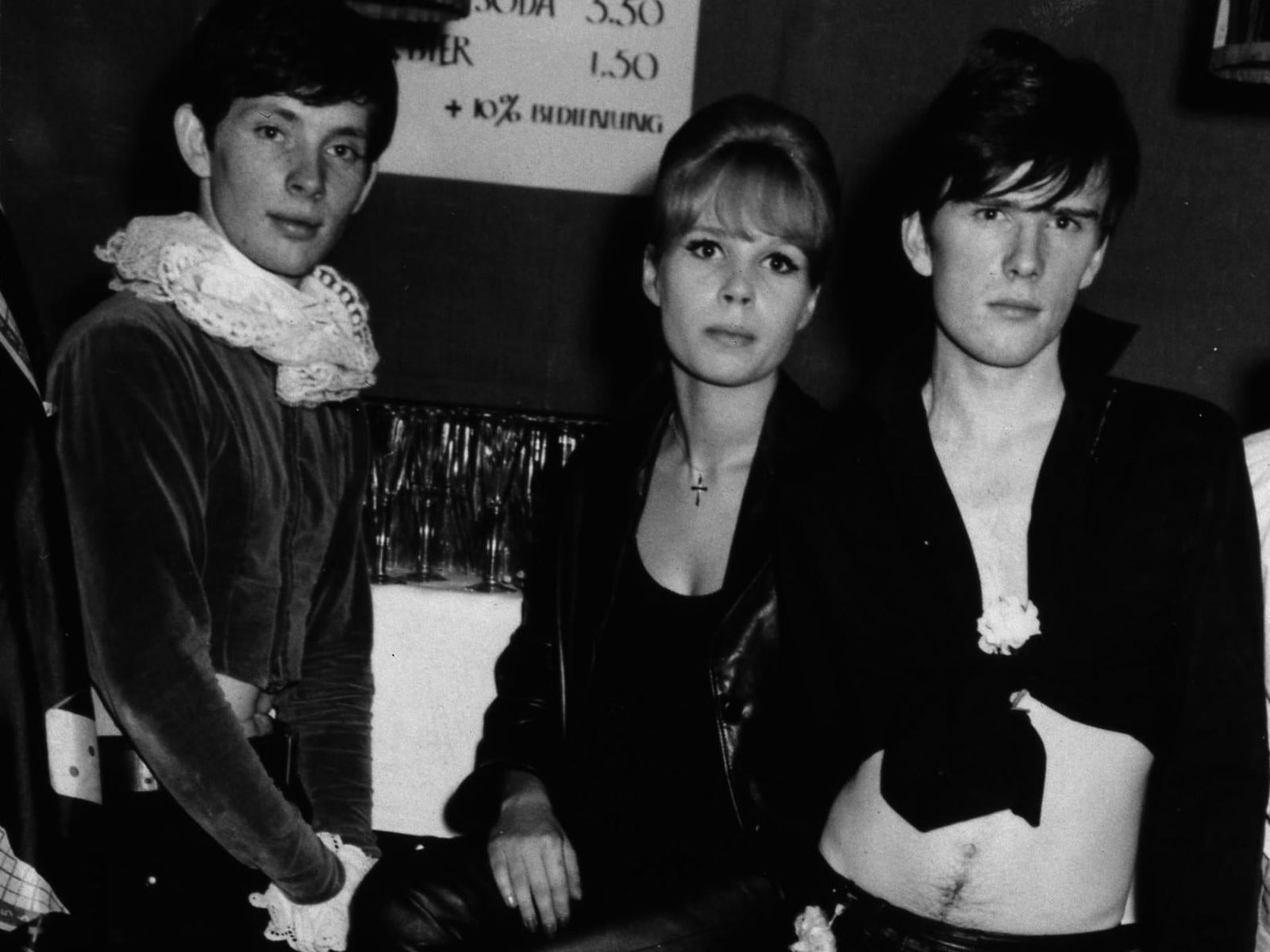

In particular, the obituaries of Kirchherr brought back briefly into focus a name that has been rarely mentioned in years: her lover Stuart Sutcliffe, one of many who have been referred to as the “fifth Beatle”, but with more claim than most to that title. Sutcliffe was bass player in the band (Paul McCartney was very much part of the band, but only took over on bass when Sutcliffe left to devote himself to Kirchherr and his painting). With his classic, moody, James Dean good looks, hair piled high, dark glasses, and intellectual persona, it was no surprise that Kirchherr became infatuated with Sutcliffe. He even smoked French cigarettes, Gauloises, cementing the air of mysterious sophistication. “I’d fallen in love with him at first sight,” she told Hunter Davies for the first Beatles biography that he wrote in 1968. “It wasn’t slushy romance and all that. I just had. Stu was the most intelligent one. I think they all agreed on that. John did.”

“They were all a knockout but my little Stuart blew my mind,” Kirchherr said. “It was fantastic to look at him and see all that beauty. Did you ever see eyes as lovely as that?” Arguably, she was not the only one infatuated with him. John Lennon, like Kirchherr, was overwhelmed by Sutcliffe. He had met him at art college in Liverpool and relished their conversations about art. He looked up to him as the better artist, though he verbally bullied him in public, perhaps to disguise his real liking for him.

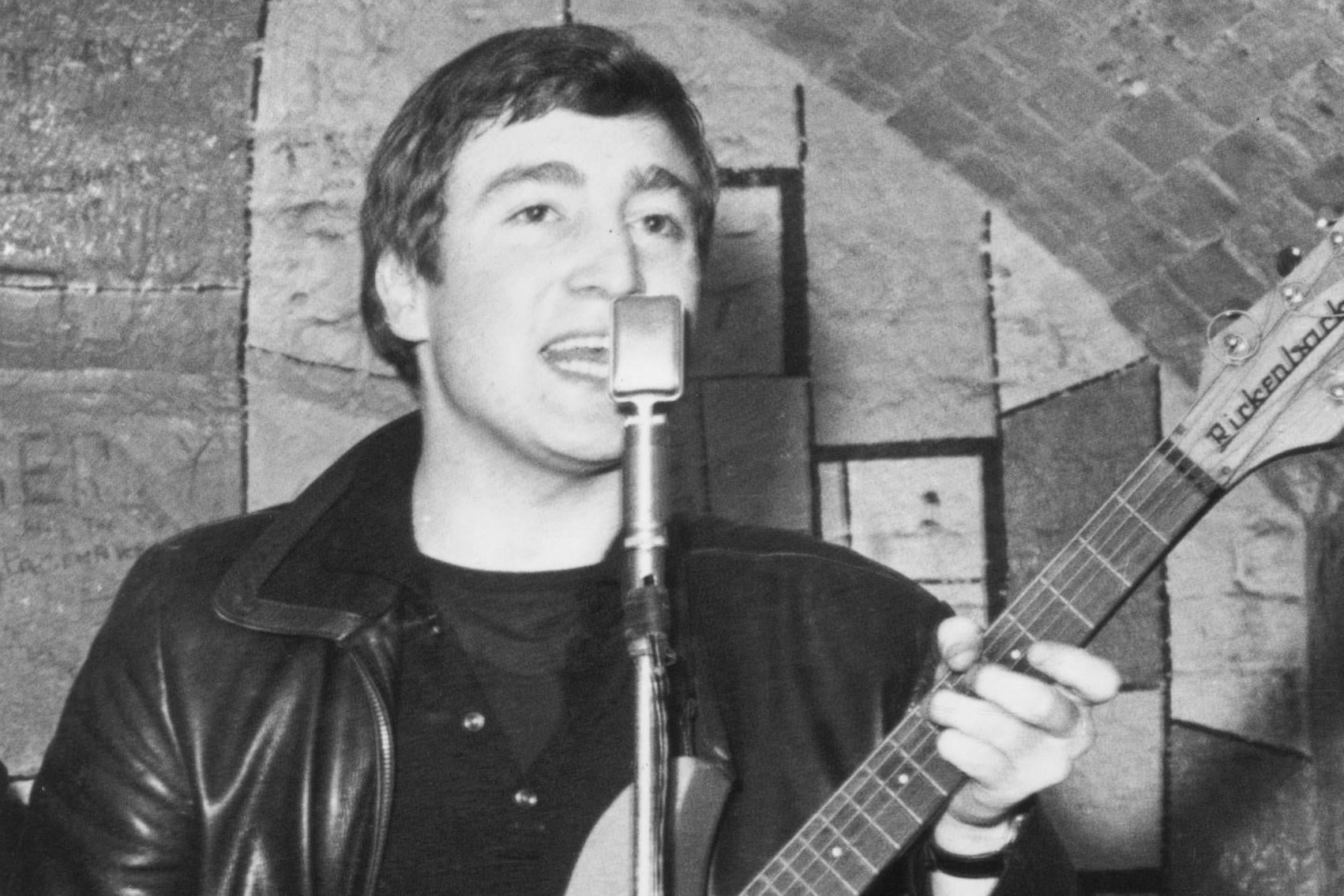

Lennon brought Sutcliffe into the band, even though its other members were not always as convinced about his musical proficiency. In the early Hamburg days, Sutcliffe would perform with his back to the audience, so that no one could see how few notes he actually played.

In other areas though, partly thanks to Kirchherr, he was the trendsetter. She insisted that he let her comb his teddy boy hairstyle down into more of a mop-top; he was the first Beatle to have one. She also made him a collarless suit, which became The Beatles’ most familiar stage uniform. Sutcliffe had even originally suggested the name “Beetles” to Lennon, after a group of girl bikers in his favourite film The Wild One. One spelling change was all it would take to become the name that everyone across the world would know.

It was as he began to spend more time with Kirchherr and develop his love of painting that Sutcliffe left the group and enrolled at Hamburg art college where the visiting professor was the Scottish-born sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi. Paolozzi said of Sutcliffe: “He had so much energy and was so very inventive. The feeling of potential splashed out of him. He had the right kind of sensibility and arrogance to succeed.”

In late 1961 Sutcliffe collapsed at the art college, and again in February 1962, staying in bed at Kirchherr’s house, writing long, 30-page letters to Lennon. Kirchherr told Hunter Davies: “He came back from a specialist one day and said he didn’t want a black coffin like everyone else. He’d just seen a white coffin in a window and wanted that.” In April 1962 he died of a brain haemorrhage.

And that for decades was as much as the keenest Beatle fan knew. Sutcliffe had left the band, had a brain haemorrhage and died. What they did not know, and few even now know, is that John Lennon may have had a hand in his death.

The seemingly far-fetched, outlandish and at first sight absurd theory did not come from some mad conspiracy theorist or the sort of nutty fans that were later to dream up the theory that Paul McCartney had died and been replaced by a lookalike. No, this was the belief of Sutcliffe’s own sister, Pauline, who wrote a book in 2001 called The Beatles’ Shadow about her late brother. It didn’t get a great deal of traction, but what it claimed was shattering.

I have read numerous books on The Beatles, but the one by Pauline Sutcliffe is the only one I can think of that was written by a woman, and a woman who also happened to earn her living as a therapist. It brought a quite different texture and perspective to the conventional rock biography. This was particularly evident in the way it explored the friendship between Lennon and Sutcliffe and hinted at how that friendship may have blossomed into a relationship.

With hindsight it was a lovely happening: two lost boys who found each other in a world where everything was new and foreign

Pauline wrote: “I have known in my heart for many years that Stuart and John had a sexual relationship.” The belief was shared by The Beatles’ veteran publicist, the late Derek Taylor, whom I chatted with over lunch some years ago. Pauline describes the Lennon/Sutcliffe relationship as a “very intense” connection “that involved part of the experimental exploring, out-of-their brain stuff. It may have happened many, many times or only occasionally, when they needed the comfort of each other in that way.”

She later said: “With hindsight it was a lovely happening: two lost boys who found each other in a world where everything was new and foreign.”

The closeness of the relationship almost certainly led to bad feelings between McCartney and Sutcliffe as they vied for Lennon’s affections. Indeed, they once had a fight on stage in Hamburg.

But if the relationship between Sutcliffe and Lennon could be tender, it could also be volatile and unpredictable, two adjectives that were highly applicable to Lennon in those early years, long before he underwent a radical change in personality to become the world’s best-known advocate for peace and love.

Pauline told how Lennon became jealous of Sutcliffe’s love for Kirchherr, and was perhaps a little jealous that he was leaving The Beatles to go back to art school. Her brother detailed to her what happened next when he returned to Liverpool to see her in 1962, not long before his death. This is how she recalled the conversation. She wrote: “One late evening [in May 1961] it all got out of control. It was John at his most random. He and Stuart were talking in the street in Hamburg and suddenly Stuart was lying on the pavement having been punched by John. He had no time to even attempt to protect himself. The brakes weren’t working for John and he was taken over by one of his uncontrollable rages: he kicked out at Stuart again and again and kicked him in the head. There was blood streaming from Stuart’s head when John finally came to his senses. John looked down at Stuart – and fled, disgusted and terrified by his attack.

“One clue to why my brother died came from the doctors who said there was an indent in the front of his skull, medically explained as the result of a ‘trauma’ – meaning a knock or a kick. In all the many official records and books about The Beatles this event is not mentioned, but I know Stuart and John had a fight because Stuart told me… Like a volcano, John blew up. Stuart did not know anything until he was splayed across the pavement. He said he could smell the streets, the debris of them; that was the only sense he had as John kicked him again and again… Stuart said John kicked him in the head, and I’m convinced that kick was what eventually led to Stuart’s death.”

Sutcliffe and Lennon continued to write long letters to each other right up until Sutcliffe’s death but Pauline claimed that Lennon privately held himself responsible for Sutcliffe dying and that much later he told Yoko Ono about the fight and his guilt at losing control. He told her he was wearing cowboy boots with pointed toes.

A few years after writing the book, Pauline sold Sutcliffe’s sketchbooks at auction. One in particular, dating to the year of the fight with Lennon, showed a tormented mind with numerous cries for help and words such as “torment”, “shout”, “explode” and “the bloody brain”. The handwriting was shaky and some of the abstract designs disconcerting. Some of the sketches he used to dissect his brain.

So, was John Lennon indirectly responsible for the death of one of his closest friends? The evidence is muddled. Alan Clayson, with whom Pauline collaborated on the book Backbeat: Stuart Sutcliffe: The Lost Beatle, which was later made into a successful movie, long ago dismissed the claim, saying the pair had discussed it and “we concluded that Stuart wasn’t beaten up by John Lennon. His condition was brought on by an overuse of amphetamines.” Clayson said that Sutcliffe was only involved in one significant fight – in Liverpool in early 1961. And Lennon’s only involvement was to wade in and help him.

It is also the case that Philip Norman, who wrote the definitive biography of John Lennon in 2009, looked carefully into this and could find no evidence to support it. He fell out badly with Pauline when he disclosed his findings. He asked both McCartney and Kirchherr about the alleged fight. McCartney said he had not witnessed anything remotely like the fight Pauline described (even though she said he had been there at the start of it, then departed). And Kirchherr told Norman that Sutcliffe would have been sure to tell her about it, if it had happened.

Pauline, though, stuck steadfastly to her account and to her assertion that her brother had confided in her about that fateful evening. She died last year. So, the narrator of the shocking tale and the two protagonists from that evening in May 1961 are all dead.

I met Pauline Sutcliffe in London when she opened an exhibition of her brother’s art (she was a tireless champion of his artistic legacy) and I also spoke to her after she published her astonishing account of what might have caused her brother’s death. Why had she done it, I asked her. “Closure,” she replied. Indeed, in the book she quotes her friend, Lennon’s ex-wife Cynthia (also now dead), saying to her: “I think it’s time to put our boys to bed.”

But the possible cause of Sutcliffe’s death all those years ago has not really been put to bed. It probably never will be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments