The restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece shows the enduring allure of Jan van Eyck

The mystery of the most stolen painting in history has captured audiences and scholars for centuries. Its latest restoration shows that a Van Eyck isn’t just a work of art, writes William Cook, it’s a time machine

I’m standing in a twilit room in Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts, watching the meticulous restoration of one of the most magnificent artworks of all time. In the new year, the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb will be returned to St Bavo’s Cathedral here in Ghent (its home, off and on, for the past six centuries) but in the meantime, anyone is welcome to come and witness this painstaking restoration process as it happens. Stripped of its dull layers of varnish and its countless clumsy alterations, this medieval masterpiece has never looked so vibrant, so alive. For the first time in centuries, you’re seeing it the way the Van Eyck brothers painted it. And what an amazing painting it is!

Standing alongside me is Helene Dubois. She first saw this painting as a schoolgirl, nearly 40 years ago. It inspired her to become an art restorer. “Seeing it up close was an incredible experience,” she tells me. Now, half a lifetime later, she’s in charge of this project, the culmination of her life’s work so far. Talking to her, it’s clear this is an emotional assignment. So why does this painting inspire such reverence, such devotion? Why do so many people get so excited about the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb?

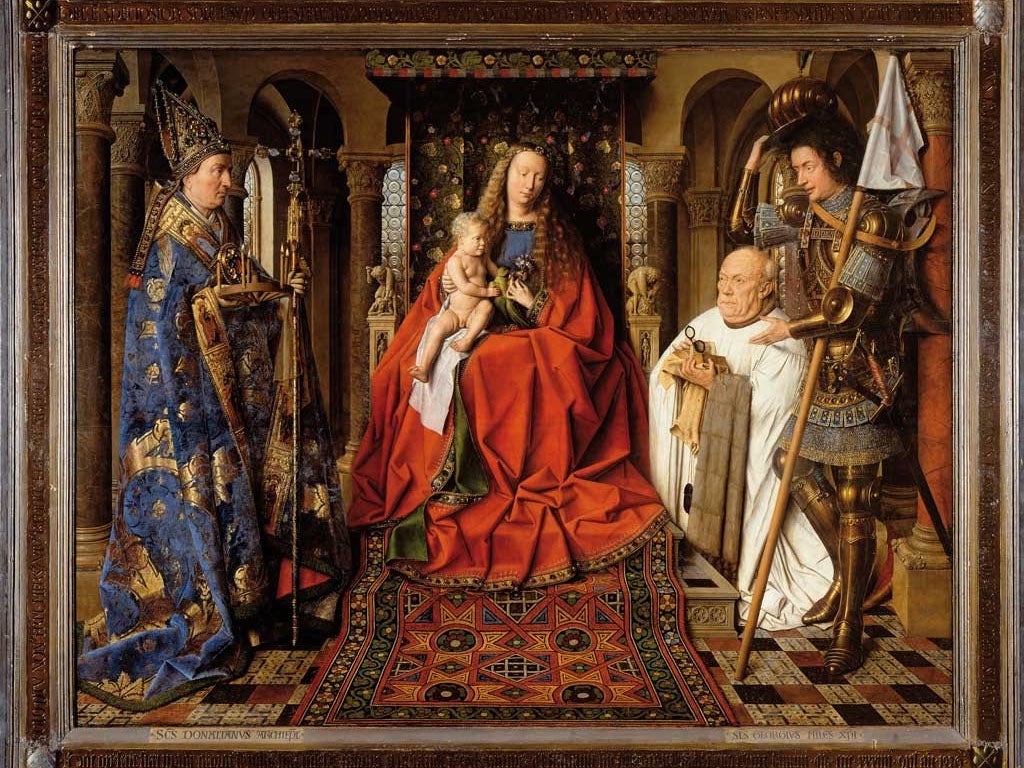

Ever since it was first unveiled in St Bavo’s Cathedral in 1432, the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb has been an endless source of fascination – an obsession fuelled by the enduring riddle of what on earth it might mean. Six hundred years since its creation, scholars are still squabbling about the symbolism of its imagery, but it’s generally agreed that, broadly speaking, it’s a depiction of the apocalypse – the end of the world as described in the Book of Revelation. The main panel depicts Jesus Christ, transformed into the Lamb of God, surrounded by all the people he’s decided to save on Judgement Day. It’s an insight into the medieval mind, a medieval view of heaven.

If the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb merely consisted of this one panel it’d still be regarded as a masterpiece, but this is just one of 20 panels depicting a vast array of worshippers, from knights in armour to choirs of angels – more people than you can count. It’s an extraordinary spectacle – disturbing and exhilarating. You can see why it’s transfixed countless generations. Originally an object of religious veneration, it’s now become even more than that – a vivid depiction of the way our ancestors thought about the afterlife. That’s why, even in our godless age, it’s such an important painting. However, it’s not just the subject matter which makes the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb so precious. Above all, it’s the exquisite nature of its execution.

“It’s a very special painting,” says Helene. “It has such high quality in painting technique.” You can say that again. Jan Van Eyck painted the people in this epic cavalcade with phenomenal precision – a level of realism never seen before, and rarely seen since. He makes other artists look rudimentary. Even in our brave new world of digital photography, it’s astonishing. Heaven knows how it must have appeared in 1432, when it was brand new. It must have seemed magical, supernatural – a sacred apparition. No wonder it was hidden away for most of the year, behind its plain and sombre outer panels, which were only opened on the holiest days in the Christian calendar. Then it became a place of pilgrimage, like the shrine of a patron saint. When it was opened up, for all to see, it always attracted a huge crowd of worshippers. One medieval commentator likened it to flies buzzing around ripe fruit.

We know relatively little about the man who made this picture, and what little we do know merely adds to the mystery of its creation. We know it was commissioned by a local alderman called Joos Vijd (his portrait is on one of the outer panels, opposite his wife). We know he hired Hubert van Eyck to paint it, and that Hubert died before he could finish it. We know it was completed by his younger brother, Jan van Eyck, in 1432.

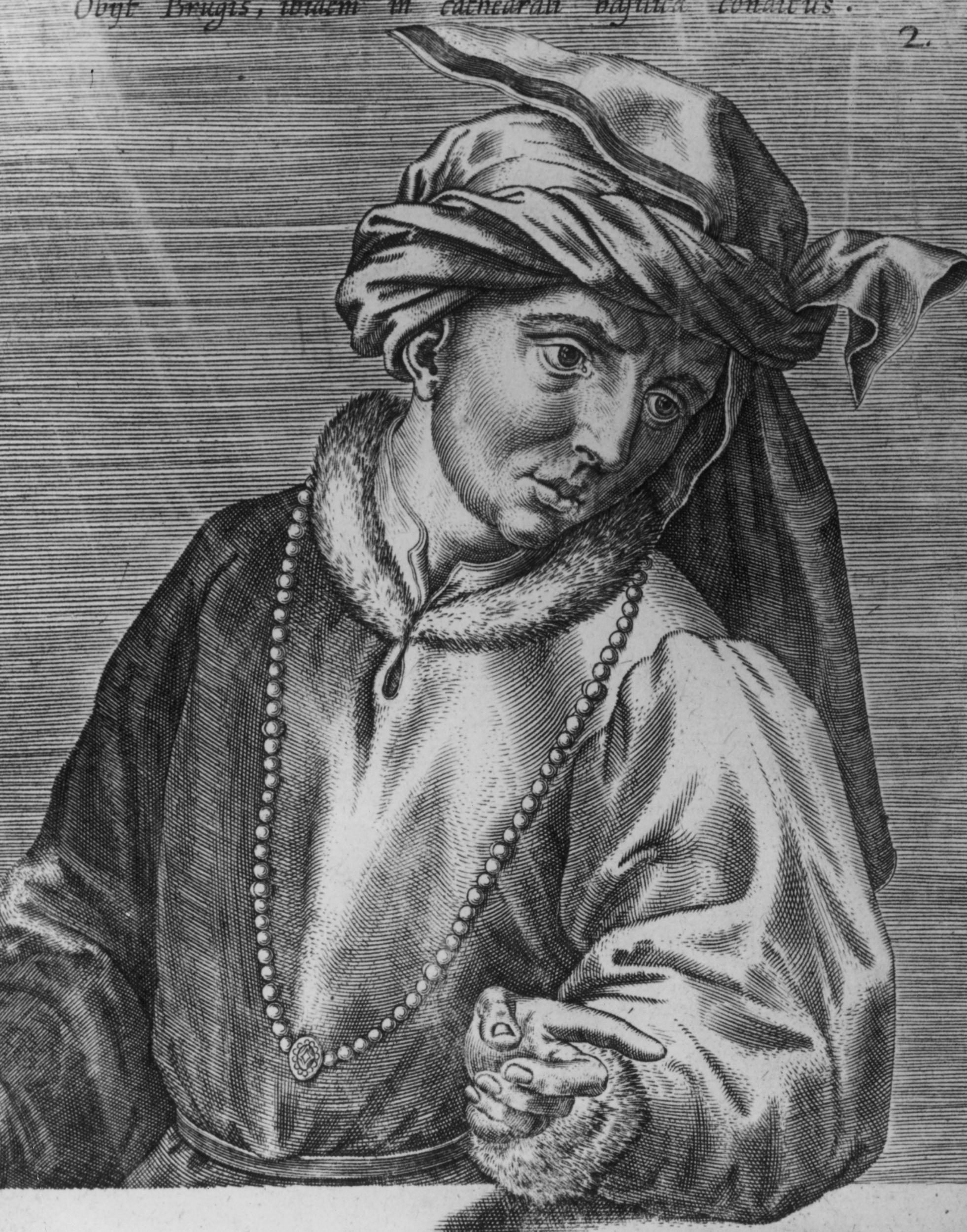

We know next to nothing about Hubert van Eyck, but we know a bit more about his younger brother, Jan. Born around 1390, in 1425 he was appointed court painter to the Duke of Burgundy and went to work for him in Lille. He moved to Bruges in 1430, where he lived until he died, in 1441. Yet most of what we know of him is of his work as a secret agent. He travelled widely as the duke’s emissary, as far afield as Italy, the Ottoman empire and the Holy Land. What exactly he was doing there is difficult to ascertain. The surviving records, reimbursing him for his extensive travel expenses, merely refer to “secret business” in “distant lands”. His official job title as court painter would certainly have given him plenty of excuses to nose around.

We do know the purpose of one mission. In 1429 he went to Portugal, to paint a portrait of the Infanta Isabella, who the duke was thinking of marrying. The purpose of this portrait, it seems, was to give the duke a good idea of what she looked like before it became too late to back out. En route, Van Eyck went to Santiago di Compostela (regarded as the end of the world before Columbus stumbled upon America some 60 years later). There, at the world’s end, he met the Christian king of Castile and the Muslim king of Granada. He may even have stopped off in England on his way back to Bruges.

Van Eyck’s extensive travels are reflected in his mystic masterpiece, which features all sorts of exotic flora, painted with botanical accuracy. But what about his brilliant draughtsmanship? His Adoration of the Mystic Lamb was pretty impressive before this restoration. Now it’s staggering. Designed to be an altarpiece, over the last 600 years it’s experienced a good deal of wear and tear, and the overpainting of previous centuries was vastly inferior. Without these crude additions, its intricate variety is revealed in all its glory. “No other painter painted like that – no one,” says Helene, emphatically.

People used to say Van Eyck invented oil painting, but this does him an injustice. There are earlier oil paintings by other artists, but they bear no comparison. What he did was far harder than mere invention: he took a fledgling art form and turned it into something fully formed. It’s not just his mastery of detail which is astounding – it’s his mastery of colour and composition.

If the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb had remained in St Bavo’s Cathedral these last 600 years, there’d still be lots to write about. However the painting has also had all sorts of adventures of its own. In 1566 Calvinism replaced Catholicism as the official religion of Flanders, and Protestant mobs tore through Flemish churches, destroying countless works of art. Thankfully the clergy hid the painting in the bell tower, so it survived.

When Catholicism was reinstated as the official religion here in Flanders, the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb was returned to its rightful place in the cathedral. However in 1794, it fell victim to an iconoclasm of a different kind. During the French Revolution, all religious institutions were abolished and all their treasures were confiscated, and when the French invaded Flanders they took the central panel back to Paris, to hang in the Louvre.

In 1815, after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, this central panel was returned to St Bavo’s, but, incredibly, in 1816 the cathedral sold the side panels to a Flemish art dealer, who sold them to an English art dealer, who sold them to the King of Prussia, who gave them to a museum in Berlin, where they were promptly cut in half. Here they stayed until the end of the First World War, whereupon they were handed back to Belgium as reparations by the Germans. The central panel was recovered from a private house (where it had been hidden during the German occupation). Finally, after a hundred years, the various panels of this spectacular painting were reunited.

Van Eyck painted the people in this epic cavalcade with phenomenal precision – a level of realism never seen before, and rarely seen since. He makes other artists look rudimentary. Even in our brave new world of digital photography, it’s astonishing. Heaven knows how it must have appeared in 1432, when it was brand new

But not for long. In 1934, someone stole two of the panels from the cathedral and held them both to ransom. One of the panels was soon recovered, but the other remained missing. The prime suspect was a Flemish sacristan called Arsene Goedertier – draft copies of the ransom notes were found in his house after he died. Unfortunately, he left no clue to the whereabouts of the missing panel. Looks like he took the secret of its location to the grave.

In 1940 Ghent was occupied by the Germans once again, and this time they took the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb back to Germany, bound for a gigantic new art gallery which Hitler planned to build in his hometown, Linz. However this massive museum was never built, and as Allied bombing raids intensified the Nazis hid the painting in a salt mine in Austria, alongside numerous other pillaged artworks. When the Allied armies entered the Third Reich and defeat became imminent, the mine was filled with dynamite and orders were given to blow it up. Mercifully, the order wasn’t carried out and the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb was saved. In 1945 it was flown back to Belgium (on a cargo plane which almost crashed in a violent storm) and returned to St Bavo’s, where it’s remained until this restoration.

Now there was only one thing missing: that stolen panel. A copy was painted from an old photograph, and although it’s perfectly competent it’s not a patch on the original. Compared to the other panels it looks flat and lifeless. It’s an accurate duplicate but it’s easy to tell apart. Will the lost original ever turn up? Here’s hoping. In the meantime at least we can marvel at 19 other panels, which constitute the greatest masterwork of the medieval age.

“You can never go back to the original painting just as it left the artist’s studio,” says Helene. “It’s aged – it’s changed.” But although her restoration may not be quite the same, having seen this painting several times before, I can confirm that it now seems revived, rejuvenated. Even if it’s not quite the picture Van Eyck painted, it’s undoubtedly the next best thing.

If you travel to Ghent next year to see Van Eyck’s restored altarpiece, you’ll be able to see plenty of other Van Eycks while you’re here. Only about 20 of his paintings survive, and you can see a dozen of them in a landmark exhibition at Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts – plus the 20 panels of the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. It really is a once in a lifetime opportunity. The last comparable Van Eyck exhibition was in Ghent in 1902. There are loads of associated events here, from music to gastronomy (if you’re here for a few days it’s also well worth making the short journey to Bruges, where two of Van Eyck’s finest paintings have pride of place in the Groeninge Museum).

Over lunch in the Museum of Fine Arts I talk to Johan De Smet, director of the museum and curator of the forthcoming exhibition. He raves about Van Eyck’s precise brushwork, and the knowledge that informs it. “It’s intriguing to see such a diversity of elements which were really new,” he says. We tend to think of Van Eyck’s era as an age of ignorance and superstition. Rather, as De Smet points out, this so-called “Flemish Primitive” was really an early Renaissance Man. A pioneer of proper portraiture and realistic landscape painting, Van Eyck was arguably the first modern artist. He painted his friends, as well as rich and powerful patrons. He even painted a self-portrait, and a portrait of his brother Hubert, amid a crowd of pilgrims in the stolen panel of the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb.

So why does Van Eyck’s appeal endure, in an era when church attendance is dwindling, and Christianity no longer commands the same obedience and awe? Well, although a lot of his paintings are religious, unlike a lot of religious paintings they’re full of life. The people in them live and breathe. It’s like being in the same room as them. A Van Eyck isn’t just a work of art. It’s actually a kind of time machine, a window into a lost age. Six hundred years since he painted it, the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb still seems magical – but nowadays its magic is of an even deeper kind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments