Jack London, the black sprinter who changed British athletics

His success remains relatively uncelebrated but the sprinter from Guyana set in motion the changes which would allow British athletes of colour to achieve the success they have today, writes Mick O’Hare

Sam Mussabini was not a popular man in the higher echelons of British athletics. He was a professional sports coach and to the Amateur Athletic Association was thus anathema. Even worse, before coaching he had been a professional athlete and had therefore earned himself a lifetime exclusion from the association. The AAA clung to the notion of the pure amateur, a noble breed forged in the public schools of Victorian England.

Sport was there to develop character – an unwavering part of the creed of the Muscular Christian – and filthy lucre had no part to play in it. It was unholy cash that had seen rugby league split for the avowedly amateur rugby union at the end of the previous century, and the custodians of other sporting bodies – despite the ethos of Muscular Christianity taking something of a battering in the mud of Passchendaele and the Somme during the First World War – were determined that the purity of their sports would not be compromised.

Rules surrounding professionalism were arbitrary, inconsistent and seemingly hypocritical – the AAA employed coaches and masseurs but crucially not paid for by the individual athletes, which apparently made a difference – and were often pursued with capricious zeal. The rugby union authorities believed that matches under floodlights smacked of professionalism while simply to have been caught watching a rugby league match warranted a lifetime ban.

In a split similar to that in rugby, amateur rowing clubs primarily in the wealthy corners of the nation such as Cambridge, Henley or clubs along the Thames in London, would ban rowers merely suspected of professionalism (which could include a bet made in the pub), either leaving them unable to row or forcing them to join one of the growing number of professional clubs mainly based in the north-east. In the meantime, cricket fudged its way around the “problem” by having different changing rooms for gentlemen (the amateurs) and players (the professionals).

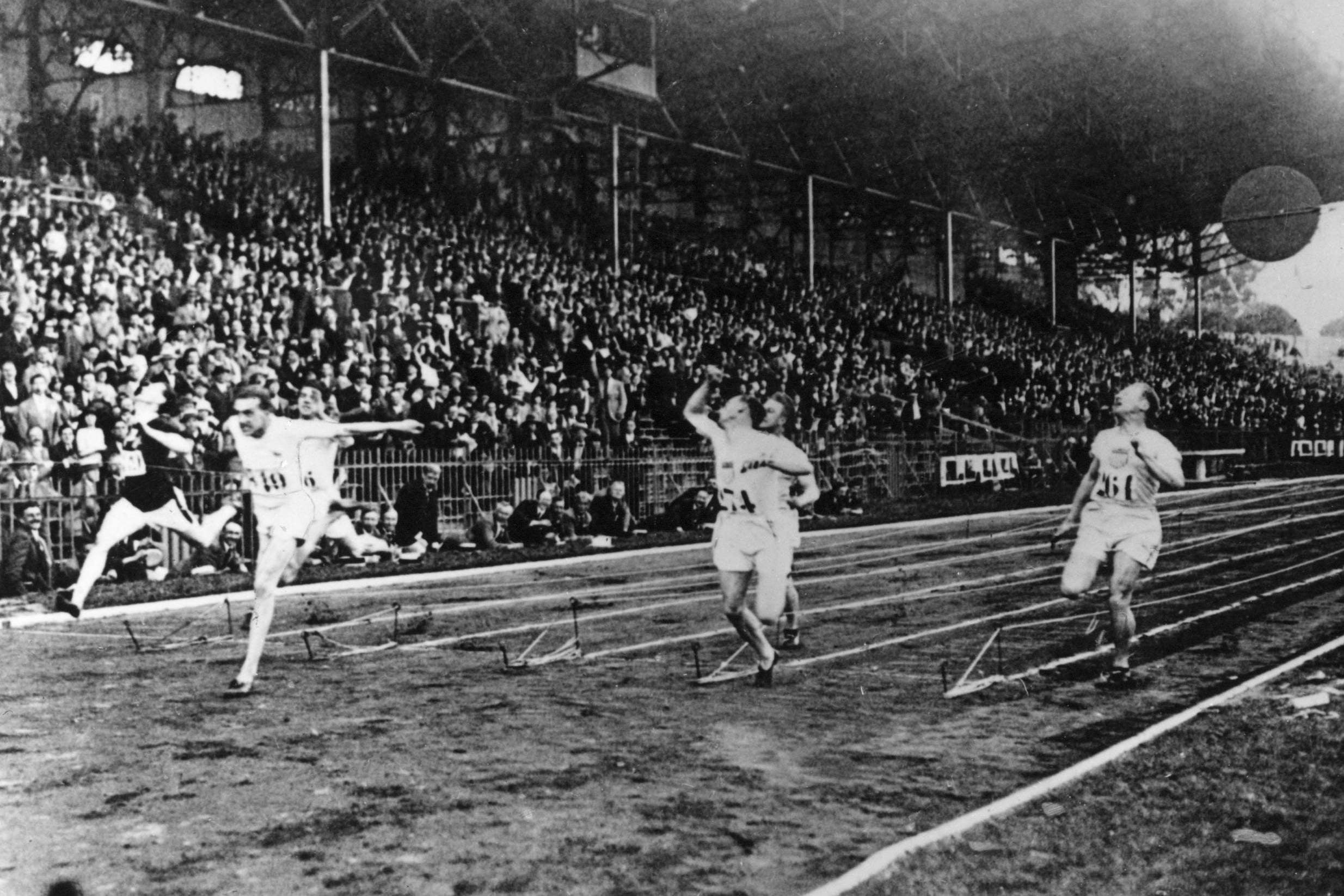

In 1924 Mussabini had coached Harold Abrahams, of Chariots of Fire fame, to the gold medal at the Paris Olympics. It fitted the skewed perspective of the athletics elite that Abrahams, a Jew, had “bought” his gold medal by employing a professional coach, a racist trope that endures today.

There was little they could do about Abrahams paying Mussabini, but they stood hypocritically aloof of such behaviour, which they considered tantamount to cheating (while simultaneously making money from charging spectators to watch their unpaid athletes). However, Mussabini was about to enrage them further. Abrahams, his religion notwithstanding, was still part of the British establishment, Cambridge-educated, upper-middle class and described by Jewish sports historian and academic David Dee in The International Journal of the History of Sport as “thoroughly Anglicised”.

Likewise it also fitted the narrative of the purists that Scipio Africanus (Sam) Mussabini was of Syrian, Turkish, French and Italian ancestry; perhaps only foreigners would defile the rectitude of what should be an amateur endeavour. But they were to be enraged further and have an additional prejudice to pick over when Mussabini took charge of a new sprinter from Polytechnic Harriers: Jack London. If Abrahams, despite his links to the higher echelons of British society, felt that he couldn’t win – simultaneously criticised for being Jewish and then guilty of “anglicising” himself – London would find himself an even more obvious target in those less enlightened times. And that’s because Jack London was black.

Born John Edward London in what was British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1905, his family had moved to Britain while he was still a baby: his father, a teacher and church minister, was studying medicine in London and although the family moved back to South America, London returned to Britain to live in Marylebone. He studied at the Regent Street Polytechnic and joined its running team, the Harriers, where he was spotted by Mussabini at the Polytechnic Stadium track in Chiswick (which still exists today).

Mussabini was – to coin a cliché – years ahead of his time. And not just because he was not prejudiced by the race, colour or religion – nor the sex – of the athletes he coached. He applied the same professionalism to his coaching as he had done to his running career.

Using techniques developed by photographer Eadweard Muybridge to study the motion of running horses, he filmed his athletes in action to better explain flaws in their technique, especially their finishing strides. He impressed upon them the importance of diet and how different foods would affect their training, fitness and stamina. Runners he coached would go on to reap 11 Olympic medals between them.

Prior to meeting Mussabini, London had never received formal athletics training, but it was immediately obvious he was quick. Mussabini would help him hone his raw talent into racing ability. London was made track captain in 1922 (he was also the club’s leading high-jumper) and by 1927 was selected to compete for England in home and away internationals in France, clocking 10.7 seconds for the 100 metres that year, a British record and only a fraction outside the world record.

He was an obvious selection for the British Olympic team, which would compete the following year in Amsterdam, although unverifiable stories suggested that some members of the AAA objected to his inclusion because he favoured using starting blocks (the first person to use them at the Olympic Games) in preference to digging footholes in what then were cinder running tracks. The spurious argument ran that starting blocks smacked once more of abhorrent professionalism. If true, whether a white runner would have received the same objections is moot.

But in the year of London’s international selection tragedy struck. Mussabini died on the journey home after celebrating his birthday in France. He was diabetic but nonetheless it was unexpected and sudden and came as a huge blow to London, who trusted and relied on his guru. He had to put the dreadful setback behind him and concentrate on the games, looming only months away.

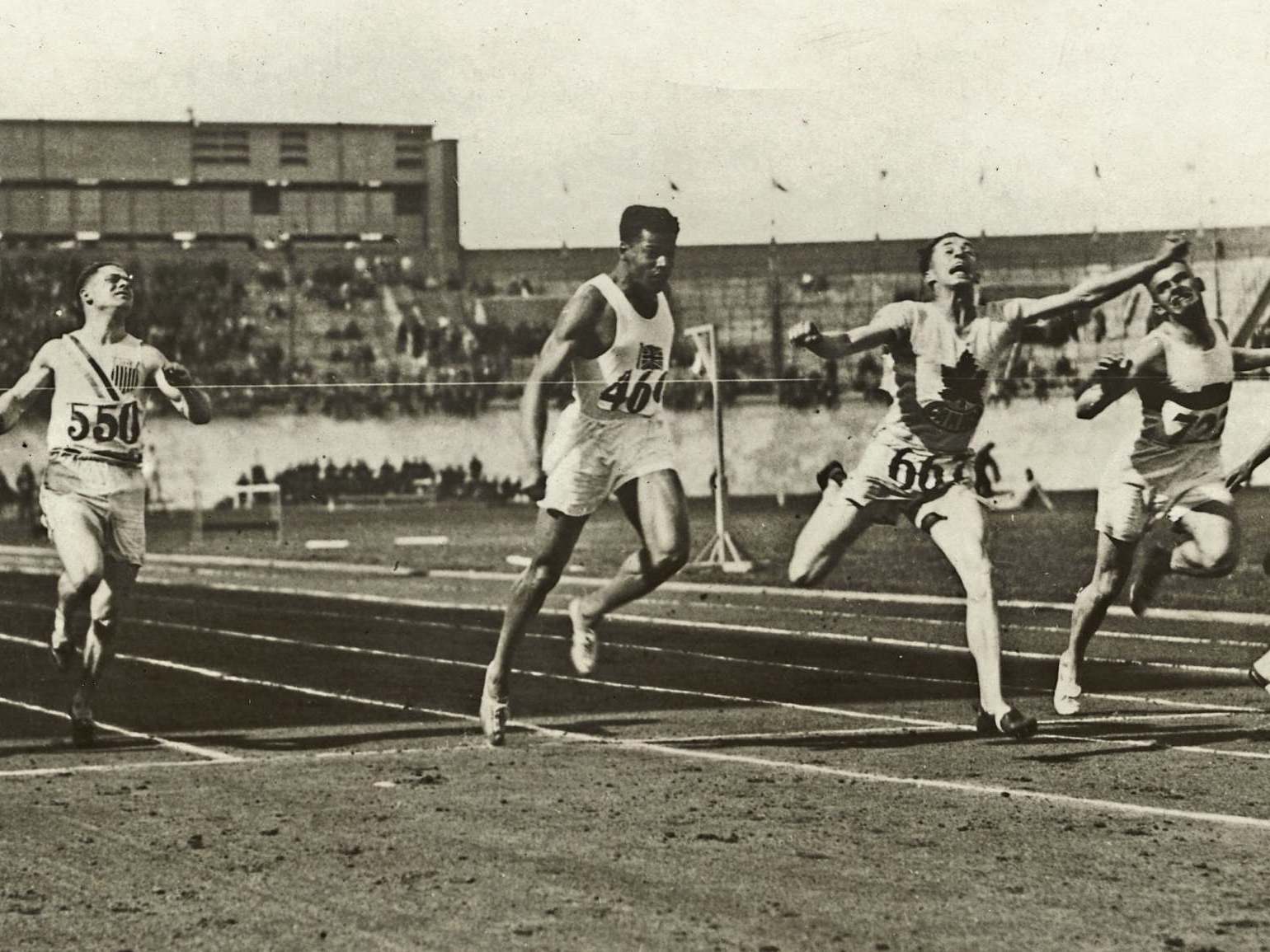

Bearing in mind Mussabini’s enduring advice – “only think of two things: the gun and the tape. When you hear one, run like hell until you break the other” – he equalled the Olympic record of 10.6 seconds in the 100 metres semi-final in Amsterdam, but elation was to turn to disappointment in the final.

Had he equalled his semi-final time he would have taken gold ahead of the eventual winner, Percy Williams of Canada, but frustratingly he had to settle for silver in 10.9 seconds. But he made history by becoming the first black person to win an Olympic medal for Great Britain. He backed it up with a bronze five days later when, with teammates Walter Rangeley, Edward Smouha and Cyril Gill, he anchored the British quartet to a bronze medal in the 4 x 100 metres relay.

It’s fair to say he set the ball rolling for the ultimate success of the likes of Linford Christie, Tessa Sanderson, Jessica Ennis and Mo Farah

Despite his disappointment at missing out on gold and the sadness that his former mentor was not there to witness it, he was awarded the polytechnic’s newly inaugurated Sam Mussabini Memorial Medal for the best individual performance of 1928. The archives of the Polytechnic Harriers describe him as “not only a champion but as clean a sportsman as ever entered the club. The award was made in view of him equalling the Olympic record 10.6 seconds in the semi-final in Amsterdam.”

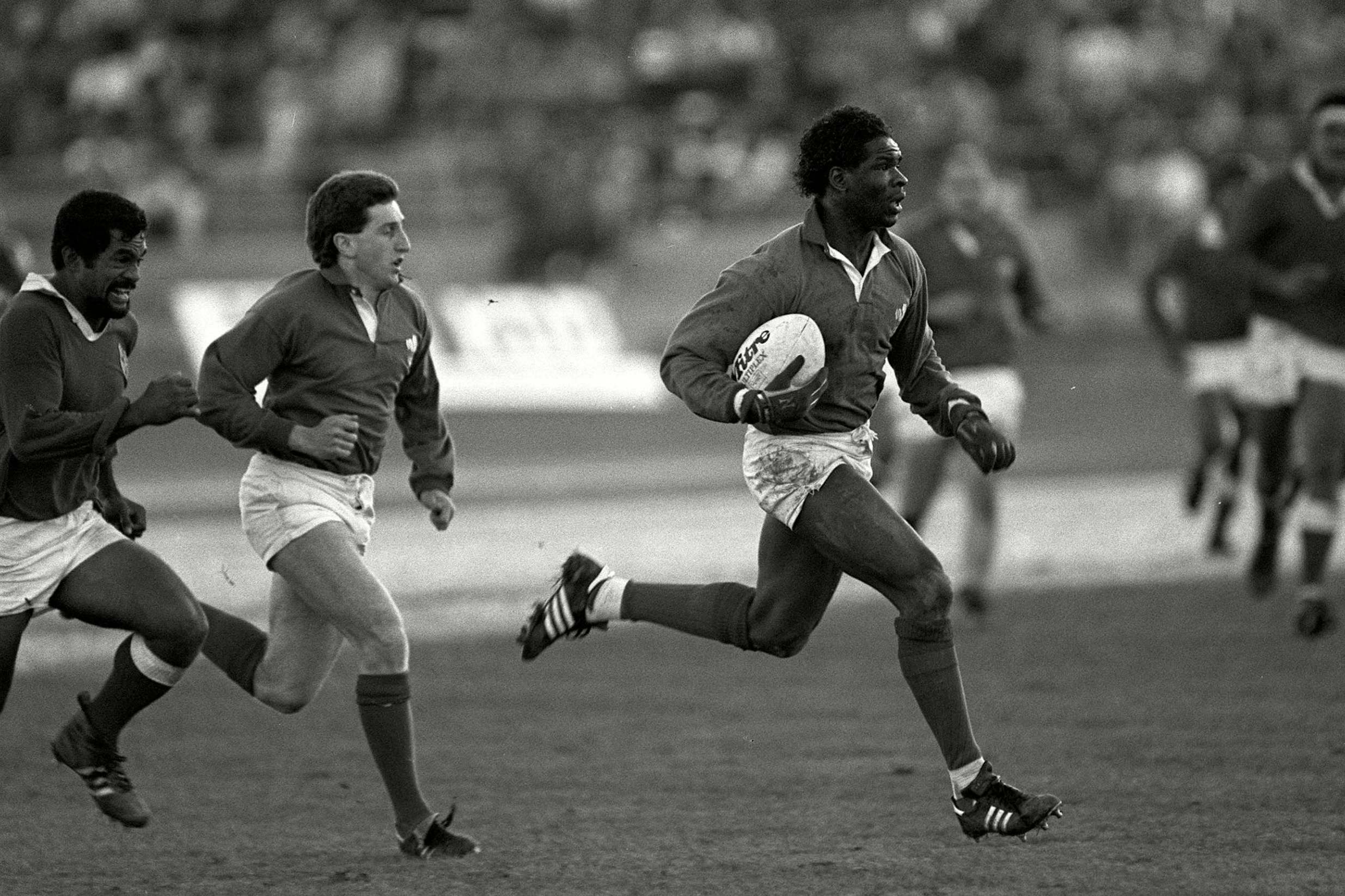

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the hidebound attitudes of the various sporting authorities were not immediately swayed by the obvious talent and success of the likes of Jack London. So while his medals marked a British sporting milestone, it would be another 50 years before Viv Anderson became the first black footballer to play for the senior England football team.

And although Welshman Clive Sullivan became the first black captain of a British national sports team when he led Great Britain’s rugby league team against France in 1970, he was something of an anomaly. The Welsh national rugby union team operated an unwritten colour bar driving Sullivan and a host of other excellent black Welsh players to switch rugby codes, aware that they could never play for their national team. It would be 1986 before that particular wall of prejudice was breached when a black player, Glenn Webbe, finally played rugby union for Wales.

But it is perhaps unfair to single out the Welsh Rugby Union. It was not alone. Such prejudice against black players and other black sportspeople was (and demonstrably still is) widespread. If sports did embrace black players it was often through economic expedience – the best sportsmen and women pulled in more paying spectators as rugby league discovered with Clive Sullivan and others – than through enlightenment.

Jesse Owens made a personal political point by defeating white “Aryan” athletes in front of Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but it cut little ice back in the United States where Jim Crow still held sway in his home state of Alabama. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the US sprinters who made their black power protest during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico city, recognised this. They were there because they could win medals for the US – but back home they still faced prejudice because of their colour.

For every pioneer such as Jack London, how many other great black and other ethnic minority, sporting talents have either not been recognised or, worse, deliberately been stymied down the decades? And while London blazed a trail for black British Olympians of the future – it’s fair to say he set the ball rolling for the likes of Linford Christie, Tessa Sanderson, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Mo Farah – his success remains relatively unacknowledged and uncelebrated. London was still defending the abilities of black athletes long after his own career had finished.

A 1948 article in an athletics journal carries his quotes underneath the unenlightened headline: “Coloured Racers Lack Stamina”. It’s a pity the author (and indeed the athlete himself) couldn’t witness the almost total Olympic dominance of black African athletes in long-distance races today.

London had hoped to go one better at the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles but his career was cut short by a leg injury in 1930 and although he attempted a comeback the following year he was never as quick and was forced into retirement. Never one to lack talent, however, he became a pianist in the original cast of the Noel Coward musical Cavalcade at the Theatre Royal, premiering in 1931, acted in movies, and with journalist Joe Binks co-wrote a book How to Win on Track and Field.

He died of a stroke in 1966 and Glen Haig, secretary of the Polytechnic Harriers for whom he competed so loyally, wrote that he had last seen London two years earlier at a club reunion when the medallist appeared “pathetically pleased to be remembered”. He added that London was “a man of great charm, shy and diffident, he would have been welcome at all times among us”.

London’s medals resurfaced, along with other items from his sporting career, including the relay baton with which he took bronze in Amsterdam, more recently on the BBC TV programme Antiques Roadshow after his great niece brought them along before putting them up for auction.

Eventually Mussabini’s contribution to athletics was rehabilitated and recognised in 1998 with the Mussabini Medal for outstanding coaches. There is also an English Heritage blue plaque at his former home at Herne Hill in south London. Harold Abrahams’s residence in Golders Green also has a blue plaque. However, Jack London’s house in Marylebone does not. Perhaps it’s about time that changed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments