IVF patients are vulnerable – is enough being done to protect them?

Some clinics are putting women at risk by purposefully upping patients’ hormone dosage to collect more eggs for IVF, reports Jessica Brown

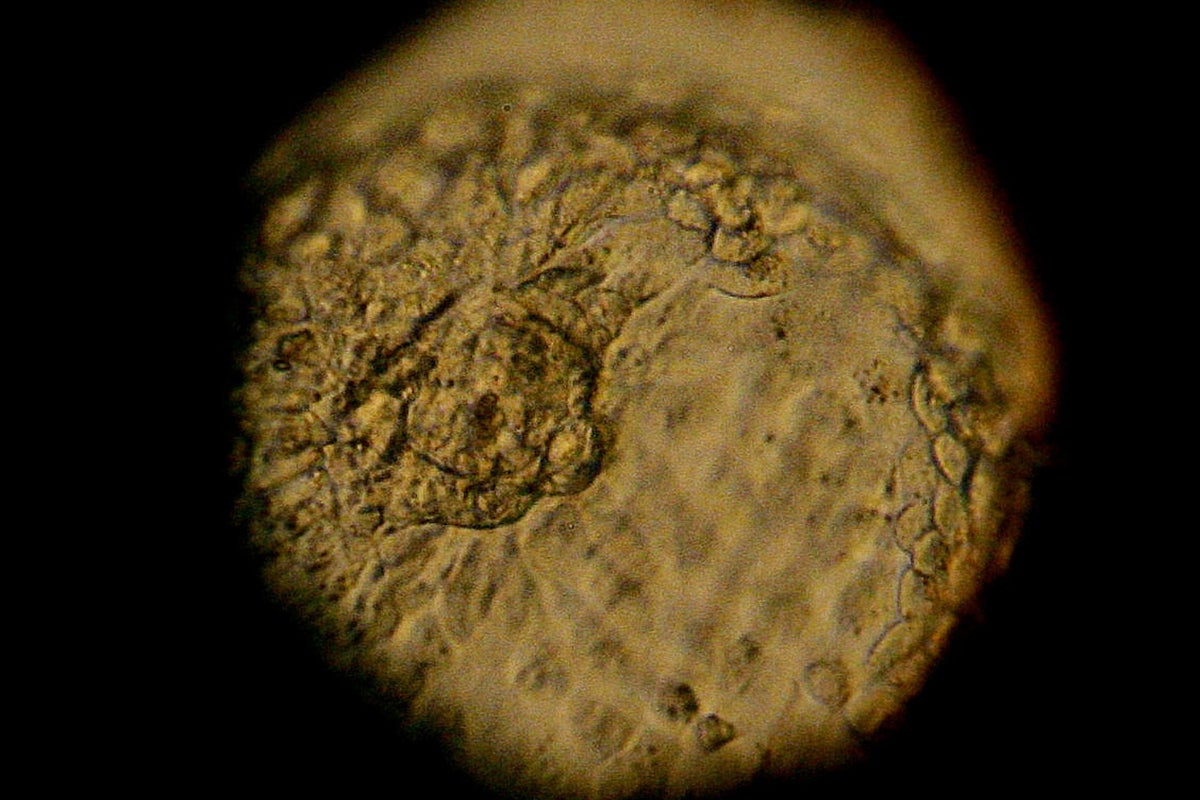

During IVF, patients are given a series of hormone injections to boost the number of eggs their ovaries release, which are then surgically removed to be fertilised. In some patients, too many eggs develop in response to the fertility medication. This leads to a mild case of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) in around a third of patients, while some develop severe OHSS, which can be life-threatening.

But some clinics are purposefully upping patients’ hormone dosage to collect more than 15 eggs, and putting women at risk of OHSS, says Gulam Bahadur, senior andrologist at North Middlesex University.

The chances of a live birth plateau after 15 eggs are collected, research has found, and the risk of OHSS “significantly” increases. When Bahadur looked at all non-donor fertility treatment between 2015 and 2018 at every IVF clinic in the UK, he found that 16 to 25 eggs were collected in 13 per cent of treatments. Although an average of 11 eggs was collected per patient, in two per cent of cases, between 26 and 59 eggs were collected, and 28 patients had more than 50 eggs retrieved.

The high rate of eggs being collected from clinics has been going on for a while, but it isn’t being acknowledged, Bahadur says. “We often talk about numbers between five and 10 eggs, but you never hear people talking about anything over 15,” he says. “This is truly scandalous, especially when you drill down into the woman’s experience, which remains taboo.

“I’ve seen only one or two publications that talk about the pain women go through when having egg retrieval procedures. It’s traumatising for these patients, who are very desperate to have a child. Pain is seen as the price they have to pay,” he says.

This practice also has financial implications for women, Bahadur says, who have to pay clinics to store their frozen eggs. This usually costs between £125 and £350 per year – altogether, a round of IVF in a private clinic costs an average of £5,000.

For Amanda (not her real name), OHSS was certainly a painful experience. During her first round of IVF, doctors collected 25 eggs. She felt slightly unwell and bloated, but nothing too serious. On her second round, they collected 30 eggs, and she developed moderate/severe OHSS.

“I was constantly short of breath, I couldn’t bend, couldn’t wear a bra, couldn’t sleep, could barely eat, was constantly nauseated, and was in constant pain. I looked like I was six months pregnant, and my whole abdomen was bloated and full,” she says.

A week after her second procedure, Amanda was barely able to function. She was in a lot of pain, and was having difficulty breathing, so she went to the emergency department of the hospital where she worked as a nurse. Her ovaries had swelled, and were pushing her other organs upwards. She was given some medication, and sent home. During that week, she lost around 12lbs in weight. No one from the clinic called to check on Amanda following her procedure.

Clinics in the UK have a single embryo transfer policy, which means only one fertilised egg is transferred at a time, to lower the chances of a multiple pregnancy, but in practice, this doesn’t always happen

“My clinic was terrible at communicating. They briefly mentioned that I was at high risk for OHSS… I did my own research, and followed all recommendations from the internet.”

IVF clinics must consider the health of their patients’ ovaries and the risk of lasting damage, Bahadur says. “There’s no follow-up of women who’ve had more than 25 eggs taken out, it’s just assumed that the ovary will heal itself. But do we really want to wait a decade or two to find out that taking out too many eggs is damaging people?”

Collecting too many eggs also increases the chance of having a multiple birth, which comes with more risk to the mother and baby, at the cost of the NHS, Bahadur says. In 2016, the IVF maternal and neonatal cost to the NHS was £115m.

Clinics should also opt for intrauterine insemination (IUI) – a fertility treatment that involves directly inserting sperm into a woman’s womb – more often as a first option. It comes with fewer risks, says Bahadur. It also costs the NHS significantly less (£3m in 2016 versus the £115m for IVF).

Clinics in the UK have a single embryo transfer policy, which means only one fertilised egg is transferred at a time, to lower the chances of a multiple pregnancy, but in practice this doesn’t always happen.

The reason clinics give patients more drugs than they need comes down to a false belief that that the more eggs collected, the better the chance of a successful pregnancy, and the better the clinic’s reputation, Bahadur says.

Clinics are in a race to have the best birth rates, Bahadur says. And while this could arguably provide clinics with an incentive, they aren’t obliged to publish the numbers of eggs collected from patients, or incidents of OHSS.

An investigation by the Daily Mail in 2017 found that there were 836 emergency hospital admissions for severe OHSS in 2015, even though the industry regulator, HFEA, reported just 60. “The people doing this have mostly got private interests, that’s the imbalance we face in our field. Too much is driven by private interests,” Bahadur says. “Women in this situation are vulnerable, they’ll do anything to have a baby. But they’re not properly counselled to give effective consent for their treatments.”

Other clinicians deny these accusations, saying that they can’t control outcomes in this way. But, in cases where treatments are particularly risky, they admit it’s often because that’s what the patient wants.

“You don’t go in collecting a certain number of eggs, because that’s not how the body works,” says Raj Mathur, senior fertility consultant at Manchester Fertility and chair of the British Fertility Society.

“You can give a patient a certain dose of medication, but how she responds is not usually in our control.”

Mathur says Bahadur’s claim that clinics purposefully increase dosage to retrieve more eggs is “outlandish”.

However, while he acknowledges that the risk of OHSS increases with more eggs collected, Mathur says that the reason most people have IVF is to have a baby, and they have a better chance of this the more eggs are collected.

Ippokratis Sarris is director and consultant in reproductive medicine at King’s Fertility clinic, where he says there hasn’t been a case of OHSS for three years. He says that, while clinicians can try to tailor doses of fertility medicine, they can’t always predict how a patient will respond to treatment. There are so many layers of complexity, he says, that it’s just not as simple as saying clinicians collect too many eggs.

“Ovaries aren’t like dimmer switches, sometimes there’s nothing, then bang – everything. No one wants to collect 50 eggs, but if that’s what’s produced, it’s dangerous to leave them in there,” he says. “I bet no one is aiming to collect 50 eggs, but it’s not easy to twiddle the switch.”

Sarris disagrees that any clinician would stimulate a patient’s ovaries in a way that’s financially motivated. But, he adds, very few patients would say they want fewer eggs removed.

Figuring out what dosage a patient needs is often “guesswork,” says Marta Jansa Perez, director of the Embryology British Pregnancy Advisory service and treasurer of the British Fertility Society. She agrees that Bahadur’s message is “alarmist and misleading”.

Even though clinics test patients to find out the capacity of their ovary to provide eggs, the test is quite unpredictable at determining how a patient’s ovaries will respond, she says. “You can’t lower the dose and risk people getting no eggs,” she says.

She delivered via a C-section and died. She never saw her baby. I couldn’t believe she’d go through that, but it taught me a lesson. She knew what she was doing

Clinicians are motivated to get a reasonable number of eggs, she says, because some won’t fertilise, and of the ones that do, not all of them will become good quality embryos. “We need to make sure patients get good quality embryos, which is why, sometimes, patients respond too well. But there are good systems in place to control the risk to their health,” she says.

For example, patients whose ovaries produced too many eggs previously would be given a lower dosage if they have another round of treatment. In fact, she adds, complications arise mostly in patients who produce lower numbers of eggs, as they’re more likely to have complex conditions in the first place.

Perez concedes, however, that some clinicians might be inclined to increase dosages because they think it will produce more eggs and give the patient a better chance of getting good embryos. This issue, she says, is a matter of funding. Currently, over 60 per cent of patients in the UK pay for their own IVF treatment in a private clinic, as they don’t qualify for NHS treatment.

Each NHS clinical commissioning group decides who can have NHS-funded IVF in their local area. They may be stricter than the NICE guidelines, which recommend that women under 40 are offered three IVF cycles on the NHS if they’ve been trying to get pregnant for two years, and haven’t got pregnant after 12 cycles of artificial insemination. Patients who aren’t overweight, and don’t have any other children, and often prioritised.

“If there was more NHS funding, perhaps there would be a shift in how people treat patients,” Perez says.

But because of the competition, she adds, clinics feel a pressure around getting the best live birth statistics. “Providers are all competing with each other for patients, therefore there’s a lot of pressure to have good results. This might mean selecting patients with a good prognosis, it might mean stimulating patients’ ovaries a bit further,” she says.

She also agrees that, ultimately, patients are willing to take huge risks with their own health. “OHSS might be one of those risks, if it means there’s a better chance of pregnancy. It’s not impossible that patients who’ve had several cycles of treatment and decide to have last go, in a desperate attempt to give it their best shot, are putting pressure on themselves to get a higher dose.

Sarris argues that every patient requires different treatment because cases are so complex. For example, Bahadur’s claim that 12 to 14 eggs is the ideal number to collect from a patient, comes from a research paper showing that this only applies to one sub group of patients having a specific type of treatment.

He argues the vast majority of clinicians do what’s best for the patient – but agrees that patients often want to take risks. “Sometimes, we know we’re going to do something dangerous; not having IVF is safer than having it. There’s a limit to what’s acceptable as a clinician, and as a patient – but they aren’t the same.”

One example that illustrates this, which has stuck with Sarris for 20 years, is the case of a patient whose heart condition meant she had a 50 per cent of dying during her pregnancy. “I saw her every day on the ward round. She was full of steroids that made her puffed up, but she was the cheeriest person,” he says. “She delivered via a C-section and died. She never saw her baby. I couldn’t believe she’d go through that, but it taught me a lesson. She knew what she was doing.”

Clinicians are there to guide patients, Sarris says, but they can’t tell them what to do. “You can make sweeping statements, but behind every number there’s a person. And if we keep that at the core of what we do, we can’t go wrong.”

A HFEA spokesperson said: “Patient safety is the most important aspect of fertility treatment and as the regulator we have robust procedures in place to ensure clinics report any incidents from treatment to us. This includes cases of OHSS.

“Some individuals may produce a high number of eggs, but as highlighted by the figures, this relates to a small number of people and can also be due to individual medical circumstances.

“Fertility treatment in the UK is more successful and safer than ever and any unsafe practices would be picked up by our inspection process.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments