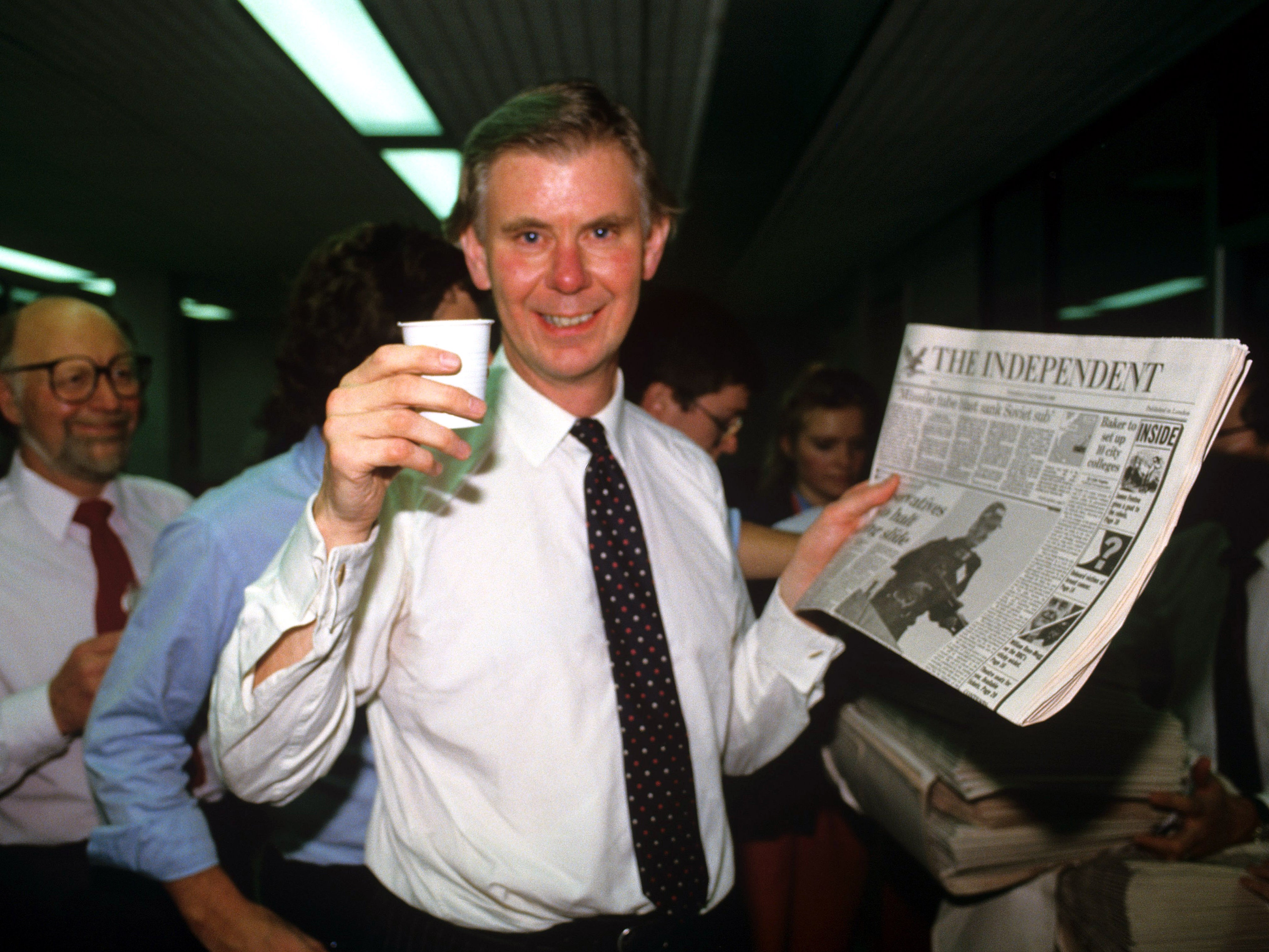

The Independent began as a start-up – and we’re still innovating

Andreas Whittam Smith explains how he effectively fired himself from The Daily Telegraph and went on to set up The Independent with two colleagues

You often read about start-ups. Thirty-five years ago, in October 1986, The Independent was one such, publishing its first ever issue. Start-ups generally comprise a group of friends with an ambitious project in their minds, who get together in one of their homes to make plans and seek useful contacts. In the case of the outstandingly successful Microsoft, for instance, Paul Allen, a programmer at Honeywell, purchased a magazine that described the first microcomputer. He immediately rushed round to his school friend, Bill Gates, to show him. The rest was history, as they say. Or, to take a famous 19th-century example, Marks & Spencer began operations when Michael Marks and Thomas Spencer acquired a permanent stall in Leeds covered market in 1894. Again, the rest was history.

The Independent began in this way but with an important difference, which I shall come to. I and two colleagues on The Daily Telegraph, Matthew Symonds and Stephen Glover, drew up plans to launch a new daily newspaper in October 1986, which was to be The Independent. None of us had been considering this daunting step for long. We began the planning in 1985. We launched a year later. Glover and Symonds were in their early thirties and I was nearly 50.

There were a number of aspects of the Fleet Street of the day that we didn’t like. Most newspapers were stridently political with right-wing views in the ascendant. Left-of-centre arguments got an outing only in the Daily Mirror and The Guardian. But by the 1980s, third-party politics had arrived.

In 1981, an electoral alliance had been established between the old Liberal Party, descended from the 18th-century Whigs, and the Social Democratic Party, a splinter group from the Labour Party. Roy Jenkins was the best known of the “Gang of Four”, senior Labour figures who broke away. In 1988, the parties merged as the Social and Liberal Democrats, adopting their present name just over a year later.

In this new age in which voters were now prepared to shop around between the political parties, we wanted the new Independent to have no party allegiance. I have always been a floating voter. During my lifetime I have more than once put my cross on the ballot paper for each of the main parties. So we would judge government policies on their merits and support or oppose them case by case.

Thus, in the early days we published two well-known columnists with completely different views – on the right, William Rees-Mogg, a former editor of The Times and father of Jacob, and on the left, Peter Jenkins. Jenkins had been TheGuardian’s labour correspondent, Washington correspondent and political commentator and policy editor.

The second unwelcome aspect of Fleet Street as it was then constructed was the stranglehold that the printing unions had over the physical production of newspapers. Overmanning (or job sharing as the unions preferred to call it) was rife. So far as the managers of national newspapers were concerned, dealing with the unions was by far the most important aspect of their task. Journalists would do what they had to do but curbing the excesses of the printing unions was the core of the newspaper manager’s job. The unions blocked technological advances for as long as they could. I remember that when I worked on The Daily Telegraph as a financial journalist in the early 1960s, it required two men to check the accuracy of the type setting: one read out what the journalist had written, the other made any necessary changes to the type setting.

What this meant was that so far as product innovation was concerned, Fleet Street newspapers were frozen in time. For as well as the inflexibility of the printing unions, wartime rationing of newsprint had continued until the early 1950s. These two factors meant there had been no creative thinking about the content and design of newspapers since 1940. There was, for instance, little coverage of health issues and scant coverage of education, two shortfalls that the new newspaper was determined to put right.

The important difference between The Independent start-up and the usual practice was that, after all, you cannot start a new national newspaper in a small, tentative way. You have to start flat out at the same size and capacity as the existing national newspapers, with their staffs of 300 or so journalists, advertising departments, circulation representatives, and printing plants strategically placed around the country. The Independent initially used four printing firms.

For all this, a large starting capital is required. In 1986 the figure was £18m. It was supplied by 40 institutional investors each one of whom I personally lobbied. The equivalent amount today would be £54m. I had the usual experiences when seeking to raise a large sum of money. An American bank with a London office said they would have loved to invest if only I had approached them earlier. The manager of a nationalised industry pension fund greeted me affably before telling me he had chucked my prospectus into the wastepaper basket. Actually he eventually invested!

News of what we were intending leaked into the Financial Times in December 1985. So the proprietor of The Daily Telegraph, Lord Hartwell, sent for me to discuss the situation. It was a conversation I shall always treasure for its civilised tone, even though the consequences for me were grave. He asked me to explain what was going on. So I described what we were doing. He thought for a moment and then asked me what I considered my situation to be vis-à-vis The Daily Telegraph. I replied that it was “untenable”. He said that he agreed.

In effect I had sacked myself for I left Lord Hartwell’s room without a job. The start-up would have to work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments