Why are single women feeling the worst effects of the housing crisis?

Households headed by single women are spending the highest proportion of their income on housing costs and are most likely to be discriminated against by a broken system, writes Hannah Fearn

When Claire*, 33, separated from her abusive partner she was living in Ireland and was determined to move her family back home to her native England. Now a single mum to three children, one with autism and learning disabilities, she needed enough money for the journey home and to put a deposit down on a property in which they could start over.

Claire’s friends astonished her with the speed at which they rallied around. She found the perfect house for all four to start over in Wiltshire, but the landlord wanted six months’ rent upfront. Her pals crowd-funded the cash and she settled in, registered her disabled 10-year-old for a special school, and claimed universal credit while she waited for the school place to come through, at which point she could finally get back to work.

“I was looking forward to this year being a fresh start,” she says. “When I moved I was so happy. It was stability; I was thinking this is a new start for me and the kids.”

But three months ago Claire received notice of her eviction, a section 21 notice stating that she had to leave by 9 August because the property was being repossessed by the landlord.

She immediately started to look for somewhere else to live but there was nowhere in her area she could afford. The rental market is so heated that some prospective tenants are being asked to find a year’s rent upfront, or offer sums over the stated monthly rate to secure homes. If Claire moved areas, she’d have to start again with applications for a special school, meaning another year or more on benefits.

“I was trying not to be fussy but to do what was right for the kids. On universal credit, I get £1,500 a month. The housing benefit element of that is £795, but £1,100 is the minimum I can find for a three-bed, and you’re then up against discrimination because you’re a single mum on universal credit. There aren’t any housing options for people like me. My money situation has been so dire the last year, I’ve had to use food banks.”

When we speak in late August – and following advice from her local authority housing advisor – Claire still hasn’t left the property. When she is eventually forcibly evicted – a trauma she wishes she did not have to put her children through – Claire and her family will be moved into temporary accommodation, which will make it harder to find housing in the private sector in future. “I’ve got 15 years of good renting behind me, and now I’ve got a massive X against my name,” she says.

Once her family is in temporary housing, her name will move higher up the social housing waiting list. But her situation is not unique. According to the charity Shelter, in the last 10 years the number of women in England who are homeless and living in temporary accommodation has increased by 88 per cent. There are now 75,000 women and their families who are homeless, accounting for 60 per cent of all homeless adults.

It’s not just the poorest and most vulnerable who are suffering. Right across the economic strata, single women are being hit hardest by the housing crisis. Whether a single parent on benefits, those living in house shares or even the few who can afford to buy their own home on one income, households headed by single women are spending the highest proportion of their income on housing costs and are most likely to be discriminated against by a broken housing system.

Emma Sandry, 35 from Cardiff, struggled to buy her own home despite having a good job and a strong deposit obtained after selling the house she previously owned with her ex-partner. Having bought as part of a couple and as a single woman, she describes the process as “so much harder” to complete alone – not just because she only had one income to draw upon, but because of the discrimination she faced from sellers.

“First-time buyers who are couples are much more attractive people to sell to because everybody likes that idea of helping people get on the ladder and the first step to creating a family,” she tells me. “As a single woman, you’re not in that desired category. It’s frustrating when people have so many offers [on their property] that they ask for more information about who you are. I must have put in offers for at least a dozen properties. It was very frustrating.”

Sandry says she “feels luckier than most” because she was able to purchase at all, and admits that was only because the first time she purchased she did so with a partner. “I’ve got lots of single friends who would love to be able to get on the ladder and because they’re single they can’t – that feels discriminatory. A lot of them are paying rent that’s going towards your landlord’s mortgage,” she says.

Also in Cardiff, 43-year-old Nicola Allen is stuck in a house share. She says the cost of housing and living as a single woman means she hasn’t been out of debt since university. “The debt is all manageable – credit card, a car loan – but it does mean that I haven’t really had the opportunity to save for a house,” she explains. “Aside from the lack of savings, my salary has also meant that undoubtedly I wouldn’t qualify for a mortgage for anything half decent in the current market. My age possibly also places a limitation on the amount that I could borrow and the time frame of the mortgage.”

I can’t help feeling like it is a sort of failure that I don’t own my own home and I often feel embarrassed to tell people that I still live in a house share

Allen has been sharing with her best friend for 17 years. The pair have lived in three properties together in that time, but the quality of accommodation they can afford has dropped in recent years. “Rental prices now mean that we are forced to live in one of the less desirable neighbourhoods where there is a lot of crime and antisocial behaviour. It is also on the very outskirts so transport and travel costs have also increased and there is very little in terms of things to do or sense of community, which feels very isolating and lonely.”

Allen describes her life as “very stuck”. She would like to change careers and leave Cardiff, but admits she cannot afford to leave her job or pay private rents elsewhere in Britain.

It’s a sentiment shared by house-sharers well into their 40s and even 50s elsewhere in the country. In London, among the most unaffordable cities for renters, 41-year-old Alicia Harvey shares with two other professional women in their 40s.

“I can’t help feeling like it is a sort of failure that I don’t own my own home and I often feel embarrassed to tell people that I still live in a house share,” she says. “I do have a chunk of savings to use as a deposit but I just don’t earn enough to get a mortgage on my own. Also, even if I could, with all the price rises I am not sure I would be able to cover all the bills alone.”

She describes renting with housemates as an “unstable” existence, but accepts she has no other option other than leaving her job and her friends behind. “I know I could move to a cheaper part of the country to give myself more of a chance, but as a single person I want to keep living in the city I have been in for the best part of two decades where I have lots of connections and a job I love. It’s much harder to make a fresh start somewhere new alone,” she says.

Alicia describes her situation – though increasingly common – as living out of step with a society set up around an assumption that women will marry and that a family will always have two incomes. She has looked into shared ownership, but in London a household income above £50,000 is often required – attainable as part of a couple, but hard to reach as a single earner.

According to research by the National Housing Federation, although the gender pay gap is narrowing in 2020/21 compared to 2016/17 (in part due to pressure imparted by government legislation insisting on publication of these statistics for larger companies), buying a house is increasingly unaffordable for single women on an average salary as wages are not keeping up with house price growth.

Data from the Office for National Statistics show that in England women still earn almost 31 per cent less than men do, on average. Meanwhile, the average house in England cost £50,000 more in 2021/22 than in 2016/17.

Although female median earnings have increased by 10.4 per cent over this period – slightly faster than house prices, and affordability has improved a little in five regions – a gender gap remains. Data on house price to income ratios exposes the extent of the problem: the median price of a house in England is 11.9 times a woman’s earnings, whereas it is only 8.2 times a man’s earnings. That means a woman would need almost 12 years of wages to buy the same house that a man could buy with just over eight years of work. A salary of £56,229 is required to buy an average-priced home in England. Average earnings for women fall short of this salary by 63 per cent and men by 47 per cent.

Importantly, the gender pay gap isn’t only explained by the work that women choose or the hours they work. A study of the gender pay gap carried out by the ONS built a model on hourly pay to try to understand the differences between sexes. It found that, inevitably, occupation had the largest effect, working patterns and geographic region were also relevant, but, as Bekah Ryder of the National Housing Federation emphasises, “nearly two thirds of the pay gap was unexplained by factors in the model”.

That means other factors, including direct pay discrimination against women, played a role. “That comes down to your ability to access the housing in the open market,” Ryder says. “It’s difficult for lone females: they’re more likely to live in poverty, and have their income fall short of that required to buy a house or to meet the rental payments. We know that access to housing is an issue that affects both women and men but there are [specific] issues for women – the gender pay gap, greater care responsibilities, women are more at risk of domestic violence.”

And while social housing supports more single mothers than any other tenures, that’s partly because they are so vulnerable elsewhere: renting statistics show that single mothers are far less likely to be offered a private tenancy than other individuals. Yet there is an acute shortage of social housing, meaning that single women about to be hit by the cost-of-living crisis have nowhere to go. “There’s going to be a huge increase in the number of people who are vulnerable and at risk of homelessness,” Ryder warns.

Rising house prices, the lack of new housing stock available and the lack of social housing all impact on rising rents and unsustainable competition in the private rented sector all impact on single women, particularly mothers. Government policies to cap the “local housing allowance” – the part of universal credit that is awarded to support the cost of housing – and to limit benefits to single parents to just two children also disproportionately hit single women. Households headed by single women are more likely to be in receipt of housing benefit; 60 per cent of those women are over 65 years old, so this isn’t a problem confined to childbearing years when the ability to work may be compromised.

But it’s not just government policy causing these problems. The social pressures underpinning women’s lives are the primary reason why single women have been hit so hard by house prices and housing shortages – and the effects are most acute for the most vulnerable women.

According to Dr Mary-Ann Stephenson, director of the Women’s Budget Group (WBG), much of the disparity in housing chances between the sexes comes down to the financial burden of unpaid care work. Even today, in 2022, women do 60 per cent more unpaid work than men. Most of that is care and domestic working, including cleaning, preparing meals, child and elderly care, and what is known as the “mental load” of remembering and carrying out every requirement related to these tasks, be that food shopping or taking a child to the dentist.

“That leaves less time for paid work, meaning they earn less and are more likely to be poor, and that’s the reason for the gender affordability gap,” Dr Stephenson says. It’s also a self-perpetuating cycle: employers perceive women as likely to be bogged down by caring opportunities and so are discriminated against at work leading to lower salaries, and the knock-on effect for housing is that women are perceived by landlords or estate agents as not being able to afford something they can.

There are also even more troubling consequences of this disparity, as Dr Stephenson explains: “Where there’s domestic violence or abuse, [it means] they find it difficult to leave violent relationships – particularly at the moment. People are reporting women looking at their finances and deciding they’re not going to leave because it’s about their kids having a roof over their head.”

Sometimes, even in spite of violence and abuse, that’s an understandable position to take. A report by the WBG into the state of housing for women in Coventry, A Home of Her Own, found that the acute shortage meant the city didn’t have any women-only homelessness provision, and there had been a series of sexual assaults in the mixed shelters provided by the local authority. There was also a dire shortage of refuge beds. After the report, changes were made – but the situation is echoed across the country.

Leanna Fairfax, a PhD student researching the experiences of single women in temporary accommodation in Leeds, is a mother who has twice experienced homelessness herself. She says the services that were available for women only a decade ago, such as support to furnish a temporary property with basics such as a bed, a sofa and a refrigerator, are no longer available. Untrained and under-prepared services such as schools are becoming unplanned support workers to homeless single mothers and their children due to extreme housing precarity.

The lack of affordable housing for women left homeless due to relationship breakdown means families are being pushed far away from the networks they rely on to survive. “One woman I was speaking to had been placed far out, away from family, far from the school,” Fairfax says. “It made her anxious and depressed, she couldn’t afford to get on buses to get to places.

“When I think about my experience [of homelessness], I just think thank god it’s not in this time period. I think we’re in a worse situation than we were 10 years ago because of the vast cuts to the welfare system and support services being withdrawn. The community care grant and crisis loan – these are things I accessed, and those services are not available now. On top of that we’ve also got the welfare cap and the two-child limit – that is particularly concerning for women who are fleeing domestic violence. If you’re having to leave because you’re in an unsafe environment but you’re thinking you’re going to be severely worse off living on £1,100 a month with four children, it’s just not enough to survive on.”

Experts say the single policy that could make a difference for single women would be to boost the provision of social housing, through huge investment from government and a rapid new development scheme. That would require accepting that the expansion of the private rented sector to do the job that social housing used to do has failed, and particularly for women and families with young children who need stability and security of tenure close to a school of their choice. Britain requires at least 90,000 new social homes a year to keep pace with demand, let alone start to make adjustments to the wider housing profile of the country; today, at an ambitious estimate, we’re building less than a third of that.

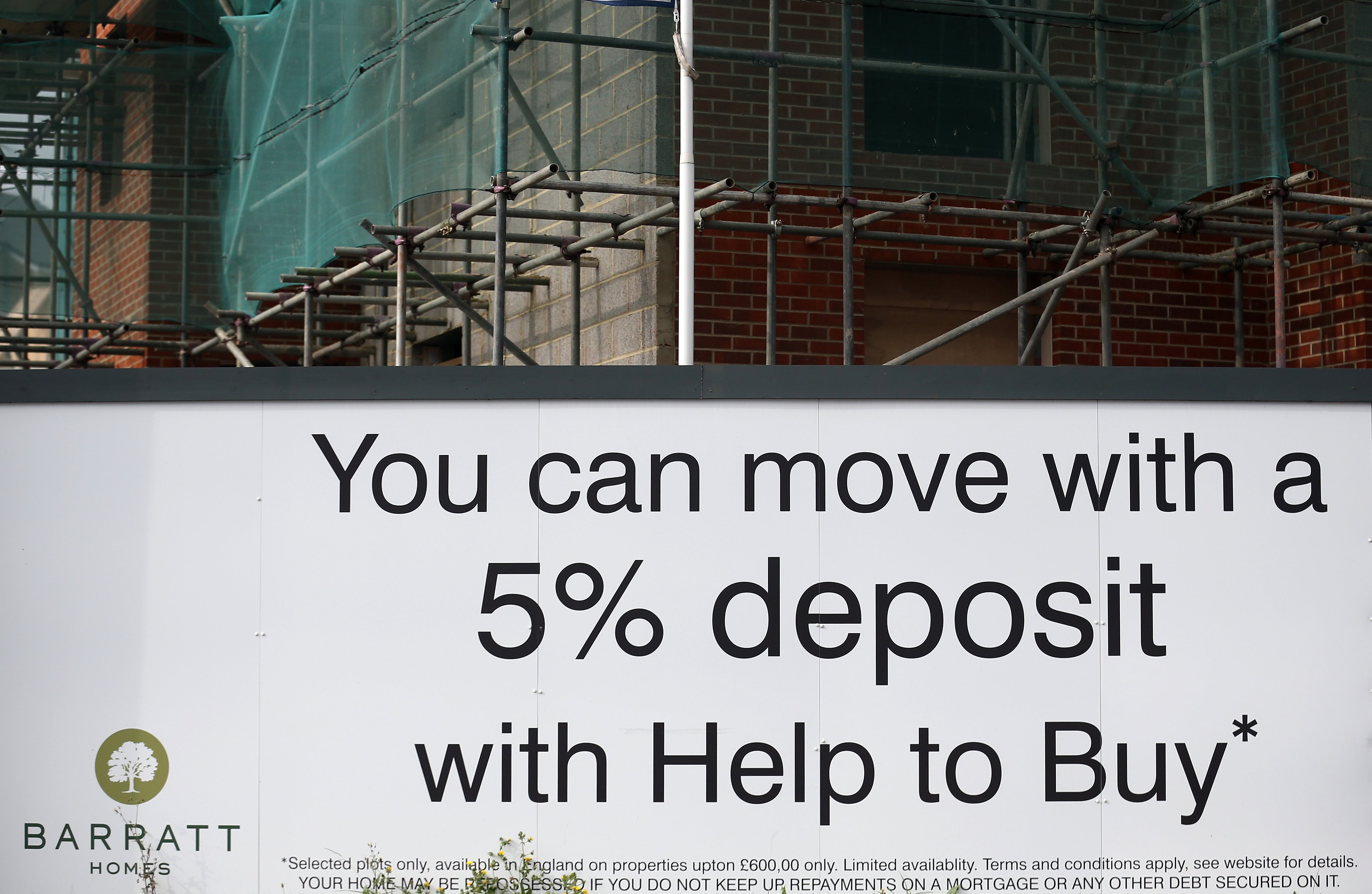

New policies such as a Help to Buy specifically for mature or single women would provide additional financial support, while also recognising that it’s not just young people who are being failed

Dr Stephenson of the WBG says: “Successive governments haven’t wanted to deal with that. It’s fascinating seeing some of the people around [new prime minister] Liz Truss talk about the ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ vision. One of the things they do well in Singapore is they build a lot of social housing! We’ve come to a point where social housing is seen as a last resort safety net for people, but we need properly provided social housing which would reduce demand in the private rented sector which would stop so many houses being sold as buy-to-let, which would also help manage house prices.”

To achieve that vision, the government would have to be willing to take on the significant proportion of the middle-income population which holds a buy-to-let property as an investment for retirement.

Some housing associations, such as Women’s Pioneer Housing Group, deal specifically with women’s housing needs. Pioneering chief executive Tracey Downie says she hasn’t yet seen any evidence that the Conservative government – or prime minister Liz Truss – have any recognition that there is a sex bias against women achieving housing security in Britain.

Though the struggle of single mums may be discussed in parliament, there is less interest in the needs of single women from their mid- to late-50s onwards. Downie says: “You may find yourself on your own and you won’t have accumulated wealth because of changes in your employment – looking after children or an elderly parent might have meant you have fractured employment – and now you have a financial history that makes it more difficult to rent or buy. Even low-cost shared ownership is still going to be heavily favoured towards men.”

Downie says her job is to make sure policymakers are talking more about these issues and to convince developers to work with small housing organisations like her own to meet these specific needs being missed by the market. She suggests new policies such as a Help to Buy specifically for mature or single women would provide additional financial support, while also recognising that it’s not just young people who are being failed by the housing market in its current form.

This is welcome news for campaigners for single women’s rights such as journalist and author Nicola Slawson, a single woman in her 30s who rents alone and authors the Single Supplement newsletter. Slawson is the host of a community of single women on social media who feel pushed off the political discussion around the cost-of-living crisis.

“They are fed up of hearing about policies for ‘families’. It should be ‘households’, because there are millions of people that live on their own,” she tells me. “Whenever support is mentioned, they don’t mention people who live on their own at all. In the energy crisis, the cost-of-living crisis – they are just overlooked. It’s like the government doesn’t even realise that there are people who live on their own. Nothing has changed despite the experience of the pandemic.”

Slawson hears from women in every situation within her community, and housing is one of the most common topics discussed on the Single Supplement Facebook group. The cost-of-living crisis is causing even more concern. “So many people in my community are feeling so anxious at the moment. All the extra cash that they could save as a buffer in case something does happen will be eaten up and they won’t have that safety net,” Slawson says. “Single people pay on average £7,000 more per year on household bills and food. If you’re living in a one-bedroom flat it costs exactly the same to heat if two people live there. That’s something nobody pays any attention to.”

And Slawson herself is living through the crisis. When she found the home she rents in Shropshire two years ago she was up against 20 other applicants, which was competition enough. Now she hears of 50 people bidding on every property. Letting agents are also encouraging potential tenants to offer a year’s rent upfront – often a sum as large as a deposit to buy a property.

“I just had a bit of a try to get on the property ladder and I just kept getting outbid,” she says. “On two incomes I could try to get more, but I can only [borrow] a certain amount and there doesn’t seem to be any kind of help. In the West Midlands you can only get a Help to Buy equity loan if the property is £250,000 minimum. Now I’m renting still and I just have this low-level anxiety constantly that I’m going to get a no-fault eviction. I don’t know what I’d do. I’m just waiting to be told there’s a massive hike in my rent and I’ll just have to accept it because I don’t want to get kicked out.”

The energy crisis is dominating the debate, but as Liz Truss enters Downing Street a second challenge will be to address the housing crisis. Recognising that women are feeling the effects of that crisis more sharply ought to be a good starting point for the UK’s third female prime minister.

*Some names have been changed to protect the identities of the people involved

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments