England is smashing HIV – so what comes next in the 40-year fight?

HIV was once a death sentence but – thanks to testing, drugs and surveillance – transmission could be eliminated by 2030. Sadly, the public perception of Aids still lags behind the scientific progress, reports Samuel Lovett

Patients were scattered throughout the hospital. Placed in rundown side wards – out of sight and out of mind – they were treated by a handful of nurses and doctors who were brave enough to care for them. Staff were reluctant to draw close. Porters would push their food trays across the floor, or simply knock on ward doors and leave the bed-bound patients to collect their own meals. Most consultants refused to treat them.

There were no drugs for the sick, most of whom were young, male and gay. Nor was there any certainty about the illness. Many were presenting with seemingly unconnected symptoms. Some had developed purple patches that dotted their face and neck. Others were laid low by a high fever and coughing fits. Muscle wastage, seizures, paralysis and blindness were also common.

During the early days of England’s epidemic, it was here, in Middlesex Hospital, where many of the first victims of HIV came to die. Dr Anton Pozniak was there on the frontline. A respiratory doctor at Middlesex, and part of a small team led by two other consultants, he treated some of the first Aids patients in England as they started to fill up hospital beds from 1981.

“We were in uncharted water,” he says. “We had no drugs. We could only treat the infections and diseases, and many were rare and hard to diagnose. It was tough being a doctor, having people around your age and watching them die by degree.”

As an illness that has now become treatable to the point of being undetectable, it is hard to imagine the horrors that once defined HIV and Aids. It was the relentless inevitability of the disease that now sticks in the mind of those who witnessed the crisis as it unfolded throughout the 1980s.

We had no drugs. We could only treat the infections and diseases, and many were rare and hard to diagnose. It was tough being a doctor, watching people your age die

Death may not always have been swift and sudden, but it was the only endpoint for the vast majority of those infected with the virus, which striped down the individual’s immunological defences, leaving them vulnerable to all manner of opportunistic illnesses – often rare and complex in nature.

Today, HIV is no longer the death sentence it once was. Thanks to antiviral treatments, extensive testing and surveillance, and greater societal awareness, huge steps forward have been taken in tackling the illness, to the point that transmission of HIV in England could be eliminated by 2030.

Since the early 1980s, much of what we knew about HIV has been turned on its head. Now, in England, the virus infects more heterosexual people than gay or bisexual men. A pill a day is all it takes to keep the infection suppressed. Scientists are making inroads into the development of an HIV vaccine. Research is underway, too, for a cure – once thought to be out of our reach.

It has taken more than 40 years to get to where we are today as a country, with tens of thousands of lives lost during this period. And for all scientific progress that has been made, public perception and understanding continues to lag behind. It has been a long and agonising journey, one that still has many years left to run – though hope for the future has never been brighter.

Prior to 1981, Middlesex had run a large outpatient department for sexually transmitted diseases and, according to Professor Michael Adler, another influential clinician at the hospital, had developed a “good relationship” with London’s gay community. “We seemed to be a natural focus for people to come,” he says. “They knew they’d be treated sympathetically and in a non-censorious way.”

But Pozniak and Alder were not only fighting a losing battle against the virus, they were also forced to contend with the challenges of treating a group of gay patients “in a very traditional London teaching hospital”.

We seemed to be a natural focus for people to come. They knew they’d be treated sympathetically and in a non-censorious way

The small team of doctors and nurses tasked with treating the sick “were not looked upon favourably”, says Alder. “There was a lot of hysteria, a lot of misinformation, a lot of homophobia. It was quite difficult managing patients.” Many of the other consultants didn’t want to get involved because of such prejudices and fear, Pozniak adds.

Against this backdrop of uncertainty and hyperbole, the team at Middlesex – and other isolated units in London – were “left in the dark” to try to save the lives of the doomed.

Gradually, it emerged that patients were suffering from what became known as acquired immunodeficiency disease (Aid). As a result, previously fit and healthy men were dying from a wide range of obscure illnesses, such as PCP (a lung infection caused by a type of fungus) and Kaposi’s sarcoma (a rare cancer that typically appears as discoloured skin lesions).

“But we didn’t know what the virus was, and there were no screening tests at all,” says Adler. No one was even sure how the disease was transmitted, he adds, despite the mounting narrative which suggested only homosexuals were vulnerable, hence the term Gay-related immune deficiency (GRID).

It wasn’t until after 1984, when the HIV virus was identified and a test was subsequently developed to diagnose the infected, that the scale and gravity of England’s epidemic started to crystallise. This meant that many of the patients coming through the doors of Middlesex Hospital – a looming, red-bricked building that was demolished in 2008 – weren’t necessarily close to death. On the surface, these men were not unwell. But they were living on spent time.

“You’d get to know these people and you’d see them regularly. They’d be okay,” says Pozniak. “Then they’d say they’ve got a bit of blurred vision, floaters in their eye. You’d know then, if you looked in their eye, that they had this horrible disease called CMV. They’d be blind in nine-10 months and then dead within a year.”

Those who developed Cytomegalovirus (CMV) – another opportunistic infection – didn’t have time to get a guide dog. Some attempted to learn brail. There were treatments that might prolong their life, including injections into the eye, but it was only a matter of time before they succumbed.

Despite the sense they were pushing back against a rising tidal wave, the spirits among Middlesex’s committed team of doctors and nurses remained high. “The camaraderie we had among our own nurses and teams was amazing,” says Pozniak. “We had this fantastic communication with the patients, their relatives, and their loved ones too. The actual spirit we generated among us all supported us.”

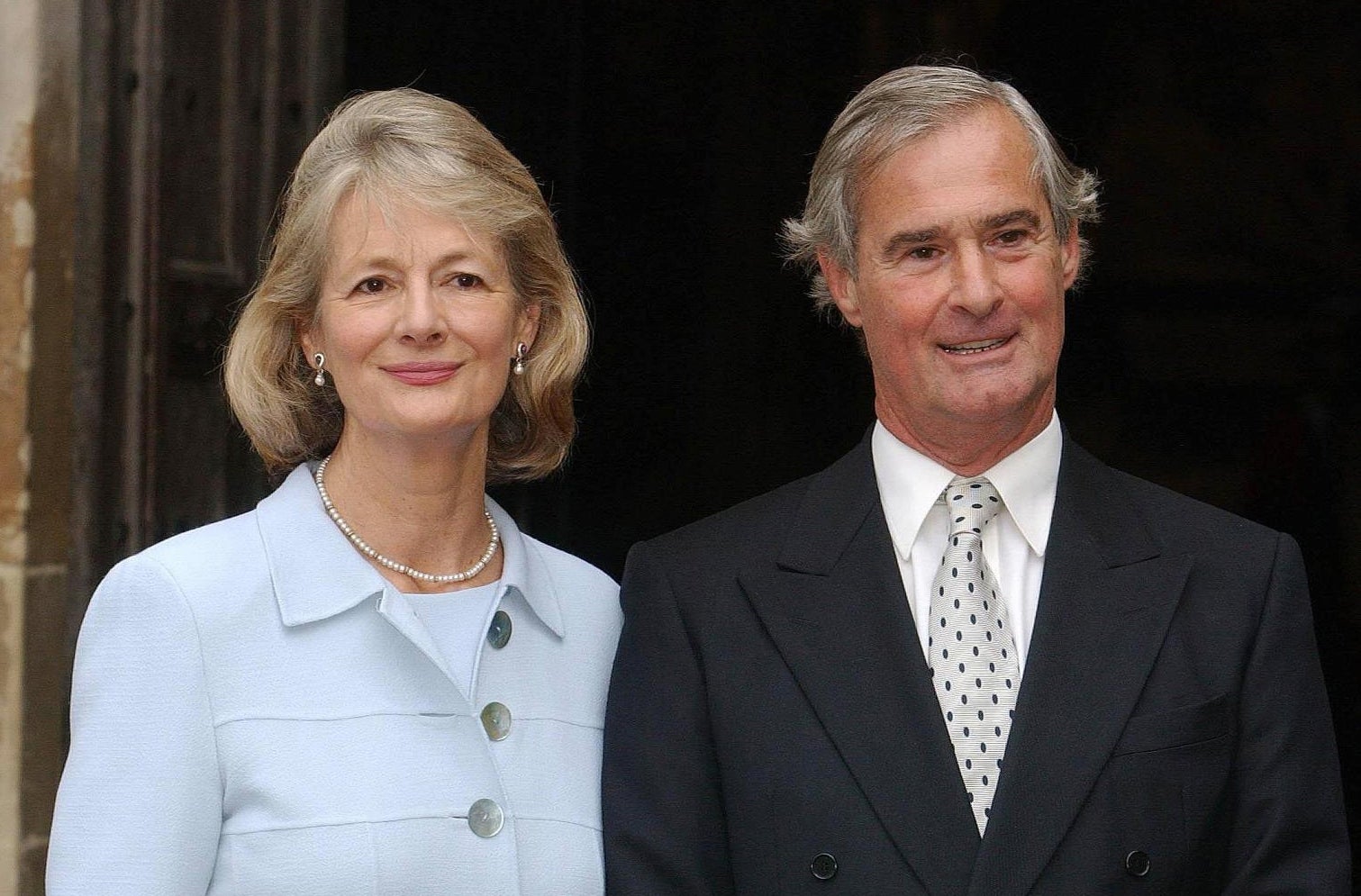

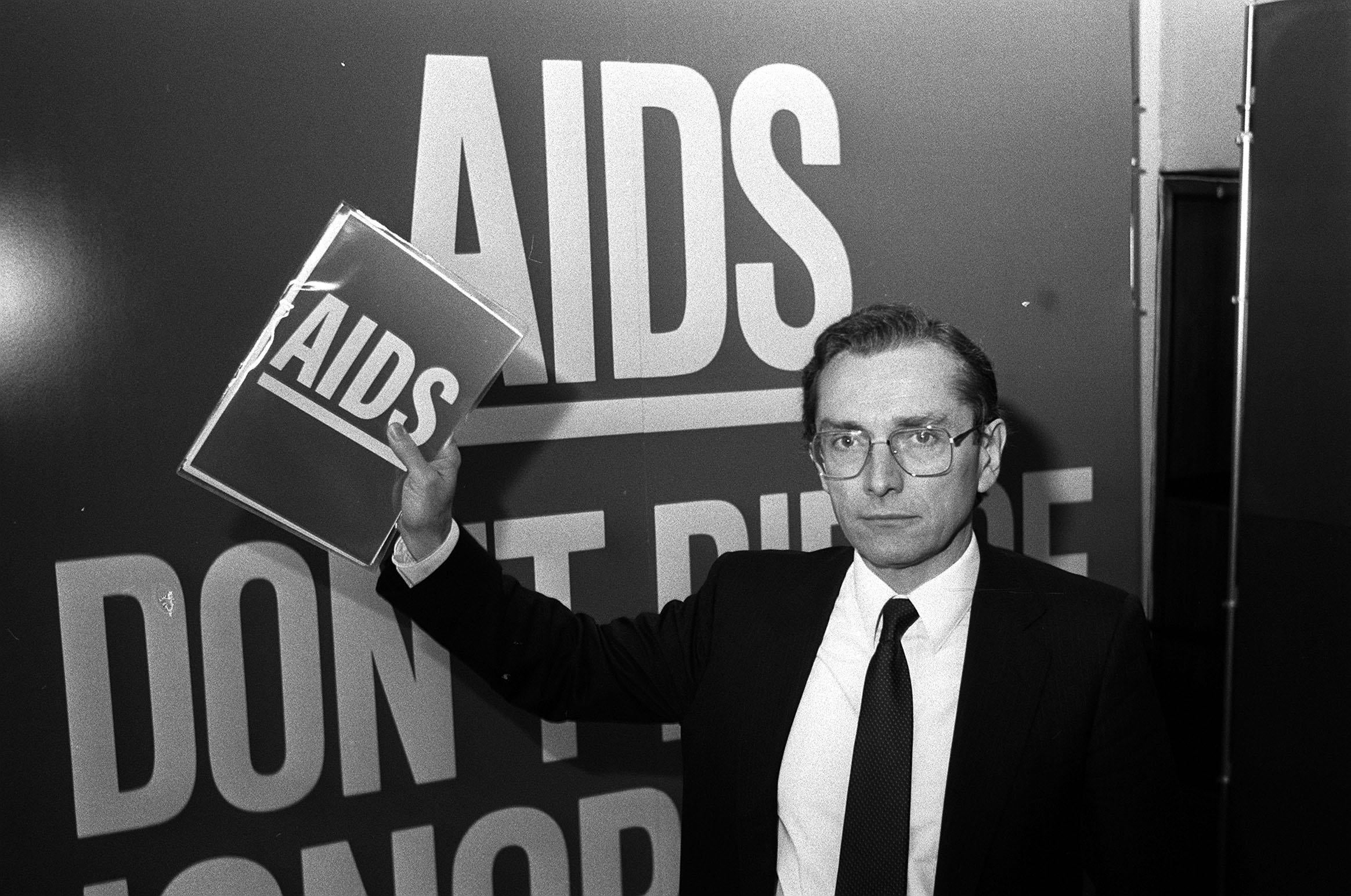

It took a brave man to stand up to Margaret Thatcher, but when it came to mobilising England’s national response to HIV and Aids, Norman Fowler was unafraid to push forward his agenda against the conservatism and traditionalism of the Iron Lady.

This isn’t to say the former health secretary, who sat in office from 1981 to 1987, had much luck – at least not right away. His attempts to sound the alarm at the beginning of the decade often fell on deaf ears.

“I can’t say that everyone else took it with sufficient seriousness,” he says, now a Lord and speaking from his office in Westminster, with views of St Thomas’ Hospital across the Thames in the background. “It was a very tricky terrain to navigate.”

On the one hand, Thatcher recognised the public health message that Lord Fowler and his team were advocating, he says, but this tended to rub up against her “Christian” morals. Early advertising campaigns that spelt out what constituted “risky sex” were knocked back out of fear of driving young men and women into the sheets.

“Her view was that it was going to teach young people things that they knew nothing about,” Lord Fowler says. “She didn’t like the profile that we were giving to HIV/Aids, which was very high, and rightly so.”

By 1985, Lord Fowler knew he was grappling with a public health crisis that was spinning out of control and would outlast his time in government. That year, 275 people in the UK had developed Aids. Of these, 144 had died. Analysis from the Department of Health suggested a further 20,000 would be infected with HIV by 1988. The warnings were bleak.

Efforts to convince Thatcher of the scale of loss the UK was facing were compounded by ministers and aides who, unlike the PM, were unsympathetic to the HIV cause because of its association with the country’s gay community.

“There was one man who was quite close to the prime minister, actually, who said that anyone with HIV should be quarantined for life,” says Lord Fowler. He also recalls conversations between himself, Thatcher and the chief rabbi of the time, Sir Immanuel Jakobovits, who “basically said that we doing the wrong thing, that we should be preaching the moral message”.

In an aide-memoire, Sir Immanuel argued that the government’s messaging should depict Aids as “a consequence of marital infidelity, premarital adventures, sexual deviation, and social irresponsibility”. In reality, research from the DfH showed that such an approach would hold no water with those they needed to reach and encourage safe practices.

This lack of empathy was reflected and reinforced in the media coverage of the time, which was whipping national anxieties around HIV into a fury. “I’d shoot my son if he had Aids, says vicar” ran one headline in The Sun in October 1985.

These extreme views were echoed by people from all walks of life, from publicans seeking to ban patients from their establishments, to the chief constable of Greater Manchester, who said that people with Aids were “swirling around in a human cesspit of their own making”.

‘I’d shoot my son if he had Aids, says vicar’ ran one headline in The Sun in October 1985

The fact that people with HIV or Aids might hold down jobs seemed particularly horrifying. Newspapers reported that people with HIV or Aids might work as airline cabin crews, bus drivers, teachers – or most worryingly of all, as doctors and dentists. Many people with, or suspected of having, HIV or Aids were fired: the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT) dealt with about 100 cases of employment discrimination each year.

Thankfully, there was a “turning point” in the government’s response, Lord Fowler says, which came in November 1986 when the green light was given to the establishment of a special committee on HIV and Aids. Importantly, the committee was not chaired by Thatcher – as others were – and meant that proposals that had been dismissed or slowed down by cabinet were suddenly injected with a new sense of life.

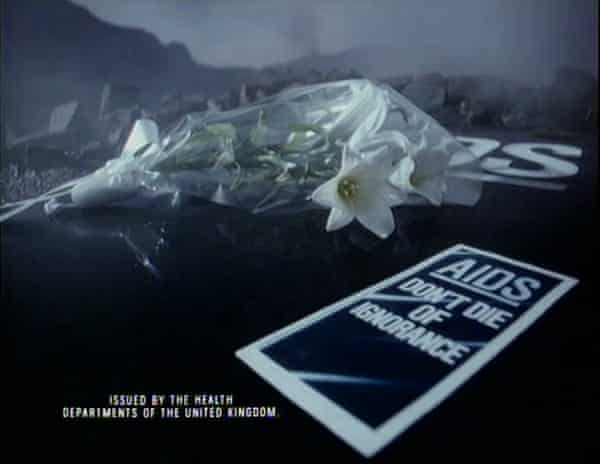

A previously opposed mass leaflet drop to 23 million households in England was approved, with their delivery – alongside an accompanying media campaign and clean needle exchange programme – planned for January 1987. For those who lived through the horrors of the epidemic, the slogan of that campaign – which was carved into an iceberg and monolithic tombstone for the TV adverts, and voiced by John Hurt – will not be forgotten: “Aids. Don’t die of ignorance.”

With its emphasis on transmission, warning that “anyone can get Aids from sexual intercourse”, the campaign was a resounding success: a Gallup poll in 1987 showed 98 per cent of the public was aware of how HIV was passed from one person to another.

“That was really the justification of the campaign,” says Lord Fowler. “HIV went down, as did other sexual diseases”.

With the passing of time, perceptions of the “tombstone campaign” have been somewhat reshaped under the light touch of historical revisionism. Commentators have observed that its messaging was too apocalyptic in tone, that it overstated the likelihood of transmission and is now responsible for the lingering assumption that an HIV diagnosis is fatal.

Matthew Hodson, executive director of Aidsmap, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1988, says the campaign was “very effective” at the time but has since cast a “long shadow. With all the glories and benefit of hindsight, it’s made an enormous contribution to the fear that people have around HIV, reflected in stigma that people with the virus face,” he says. “But I do believe it was well intentioned.”

Ian Green, the chief executive of THT, says there hasn’t been “anything like that since”, and argues that “more positive messaging is needed around the fact that HIV has changed so much and is no longer a death sentence”.

Nevertheless, the campaign – and Lord Fowler’s wider work – helped fuel the flames of activism that were beginning to flicker in society. Charities like National Aids Trust, George House Trust and Positively UK all emerged from this rising spirit, which took hold in the second half of the 1980s.

And by 1987, after a “big push” from Adler, Pozniak and the team, the country’s first dedicated Aids ward was opened at Middlesex. “This meant we had our own staff who were trained. There were none of the issues about people not prepared to look after patients,” says Adler.

The cherry on the cake was having Princess Diana visit Broderip Ward for its grand opening. What’s more, the nation’s sweetheart was photographed shaking the hands of a patient – an iconic moment that changed the national conversation around Aids. “That had a profound effect,” says Lord Fowler. “You had this very beautiful woman, clearly not wearing any gloves, not afraid of being infected, actually touching the patient. The photo went all around the world and was extremely important in changing attitudes.”

A year before that moment, Norman Fowler had been warned by the PM that he “mustn’t become known as just the minister for Aids”. Yet, looking back, there is no doubt that his efforts in tackling the disease, which continue to this very day, will outlast him. Indeed, without his legacy as “the minister for Aids”, how many more lives would have been lost?

“A lot was pinned on the introduction of AZT,” says Alder. First developed as a cancer drug, azidothymidine was touted as a game-changer for HIV patients when it began to filter into use in England throughout the late 1980s.

Rumours about the drug had been circulating since early 1985, when word came from America that a company in Carolina had found a compound that was effective against HIV – at least in a Petri dish. Two years later, by the time AZT had been licensed for use in England, demand for it had grown to gigantic proportions. “There were short supplies of AZT,” says Adler. “My office was broken into and all my writing desk drawers forced open. It was suggested that was because people were looking for drugs. AZT was heralded but it wasn’t the answer.”

The success of the drug in the lab wasn’t replicated in the real world. Yes, those on AZT had a decreased number of opportunistic infections and showed improvement in weight gain and T cell counts. But because the “virus became resistant to AZT very quickly, people got very sick again,” says Ravi Gupta, a professor of clinical microbiology.

Consumed every four hours, AZT was an incredibly toxic drug, causing chronic headaches, nausea and debilitating muscle fatigue. But its apparent ability to “buy time” made it a drug worth taking – even if its effectiveness was widely contested at the time – and offered a first glimmer of hope for patients.

You got so well that you put on weight, the rashes on your face, the diarrhoea, disappeared. The fatigue went away. Suddenly you were feeling well and looking forward to having a normal life

The real breakthrough came with the advent of triple-combination therapy in 1996, announced to the world at the famous Vancouver conference in Canada. This approach saw patients take three different drugs at the same time and was highly effective in preventing viral replication and overcoming the problem of drug resistance.

In the same year, the treatment was standardised across the NHS and its rollout in hospitals began, ushering in a new era in England’s epidemic. “We stopped counting bodies,” says Pozniak. “You not only got better from your Aids illnesses, but the majority got better.

“You also got so well that you put on weight, the rashes on your face, the diarrhoea, it disappeared. The fatigue went away. Suddenly you were feeling well and looking forward to perhaps having a more normal life.”

Patients who had resigned from their jobs and signed on to benefits, many of whom were working their way through a personal bucket list, were given a second chance at life, says Pozniak. “The treatment was transformative.”

The annual number of deaths in the UK, which had been approaching 2,000 by 1995, subsequently dropped at a “dramatic” rate, says Hodson of Aidsmap. “That changed the landscape,” he adds.

The provision of the drug through the NHS cannot be overstated. Compared to the insurance-based model in the US, which was gripped by an HIV epidemic far worse than the UK’s, the system in Britain meant the majority of patients could access triple-combination therapy with ease.

England’s huge network of STI clinics, where a lot of patients were being looked after as outpatients throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, accelerated the process by which diagnosed patients were treated. “We were well set up,” says Adler. “We also had very good support from government health bodies in collecting data and making sure it was good quality.”

Not all were so lucky, though, Hodson says. “I can name eight people who died as a result of Aids in my friendship circle after the introduction of treatment. Their bodies had been so assaulted by HIV before the treatment was available, that they weren’t able to fully bounce back.”

Debbie Gold remembers the rush of emotion when the Court of Appeals decision came through. It was, as she says, a “David versus Goliath” case: the National Aids Trust (NAT), a London-based charity led by Gold, up against the might of NHS.

After months fighting the health service, it was announced on 10 November 2016 that the NHS could and should legally fund the provision of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) as part of England’s strategy for combatting HIV. “We were delighted we’d won, beyond delighted and relieved and vindicated,” says Gold. “It was incredible, really incredible.”

PrEP is a drug taken by HIV-negative people before and after sex that reduces the risk of infection. Today, it is targeted at anyone deemed “at-risk” of catching the virus and is available via the NHS from all sexual health clinics.

Use of PrEP in England, both as part of a trial and from private purchases, was partially credited in a drop in diagnoses among gay men in 2015-2016, after a five-year plateau in diagnoses. Its impact has been revolutionary, helping the country to reduce transmission and shrink its epidemic.

However, were it not for the efforts of Gold and the NAT, PrEP would not have been as widely accessible as it is now. Despite the early “Proud” trial which pointed to its effectiveness, the NHS pushed back on calls to roll out the drug on a free and open basis, arguing it was not legally able to commission or pay for PrEP as it was deemed a preventive measure.

“The NHS argued it could only pay for treatment, not prevention, which is the responsibility of local authorities,” says Gold, who consulted with lawyers to determine whether the NAT had the grounds with which to challenge the health service over its position.

“It was a hard decision as we are a small charity and there was a lot of risk in taking legal action, both repetitional and financial. But it really felt like this was what we were for.”

The NAT went equipped into battle with an arsenal of points that it thought would cut through the NHS’s legal defences. “Some were very technical, like the specific wording of sentencing in the acts. Some were arguments about the fact that NHS does fund prevention,” says Gold.

One of the charity’s key points of attack was that “there is no clear blue water between prevention and treatment”, with PrEP a prime absolute example of that. “In order to be effective, you take the tablet, it does nothing to you unless you acquire HIV, in which case it kills it off and stops it replicating,” says Gold. “So you could say it’s early treatment of HIV.”

The High Court ruled in favour of the NAT, as did the Court of Appeals after the NHS attempted to overturn the initial decision. The latter concluded that the health service should never have dropped PrEP from the new treatments being considered for NHS commissioning.

A large PrEP trial was established by the NHS post-2016, in which tens of thousands of participants took part, before it was announced that the drug would be available to all people considered at risk from April 2020. “We’re very proud of what we achieved,” says Gold. “PrEP is one of the reasons we’re making progress to that 2030 goal.”

Becky Pullin is white, female and heterosexual. In the eyes of many, she does not match the typical profile of an HIV patient. Yet in August 2015, at the age of 29, she tested positive for the virus.

Four or so months after separating with her husband, Becky, from Sheffield, slept with another man. She subsequently started suffering from night sweats and fever – symptoms that made her think she had flu. At no point did it cross her mind that she had caught HIV.

Because I was an older woman, who’d been in a longer-term relationship, who was white and educated and in a professional role, HIV wasn’t a consideration at all

“Because I was an older woman, who’d been in a longer-term relationship, who was white and educated and in a professional role, HIV wasn’t a consideration at all,” she says. “It just didn’t enter into my head until they asked and then I subsequently tested positive.”

Despite being “immediately” told that she could still enjoy a “long and healthy life”, Becky’s thoughts turned fatalistic. “It’s still there in your head, that if you get HIV, you’re going to die.”

Yet four weeks after she started taking her medication, the virus in Becky’s body had been suppressed, meaning it was undetectable and untransmittable, otherwise known as U=U. Her chances of passing on the virus to another partner are now practically zero.

Knowledge of U=U was first communicated to the world in 2008, but the stigma of being an HIV patient still persists to this day. “We haven’t progressed as far in terms of attitudes, understanding and compassion towards people living with HIV, as we have in terms of our ability to treat and prevent it,” says Hodson.

Research commissioned by THT in 2019 suggested that almost half of Britons would feel uncomfortable kissing someone with HIV, while just one in five are aware that the virus cannot be passed on if a patient is taking effective treatment. Shockingly, 38 per cent said they would feel uncomfortable going on a date with someone who is HIV positive, according to the survey of 2,075 people. “The research suggested that knowledge of HIV has hardly moved on over the last 40 years,” says Mark Lewis, a senior policy officer for the All Party Parliamentary Group on HIV/Aids.

It’s because of these dated perceptions that Becky Pullin did not believe HIV to be a threat, yet research from the UKHSA showed last week that the number of new HIV diagnoses in heterosexual people are now higher than those in gay and bisexual men.

Of course, anyone can be infected, and with almost 5,000 people thought to be positive but undiagnosed in 2020, the race is now on to broaden out England’s public health campaign beyond the traditional focus groups – white, gay men – and into those groups and communities where HIV remains an unrecognised, or taboo, topic.

Carlos Corredor has been working with Latin American people with Aids since the mid-2000s, when he first moved to London from Colombia. Many of the patients he encounters through his charity, Aymara, are migrants and struggling to access treatments due to language barriers and “the feeling they don’t belong or qualify for care”.

“These people are living a very bad life,” he says. “They have very low paid jobs. They have to work long hours. They have very bad accommodation conditions. You have to take treatment tablets with a full stomach, but these people barely have £5 to their name to buy a meal.”

Carlos helps his patients access the right services in London and sets them on a path where they can learn to live with HIV. “We have excellent clinics, excellent medicine, excellent treatment, but we need to link everyone to these services,” he says.

5000

The number of people in England thought to be HIV positive but undiagnosed

His messaging doesn’t just apply to England’s impoverished Latin American communities. Like many others, Carlos believes that to get to the 2030 target, messaging around PrEP, U=U and testing needs to be carried into what he calls “invisible populations”.

“We need to go into those areas where nobody has been before, where the people don’t know much about HIV but are sexually active, or fear that a diagnosis will culminate in deportation,” he adds.

There is some way to go in turning the “invisible” into “visible”, but the arc of progress is no doubt bending in the right way – as seen in 2012, when treatment was made freely available for all undocumented migrants and non-UK citizens. At the time, around a quarter of all people living HIV in the UK were undiagnosed; now, this number stands at 5 to 6 per cent.

But with 20 per cent of new diagnoses occurring annually in populations that aren’t gay, bisexual or Black African, according to the NAT, there is clearly more to be done. Not just for the marginalised and overlooked, but people like Becky Pullin, too – those who never considered themselves at risk.

To further help England get over that finishing line in the fight against HIV, campaigners have called for the introduction of “opt-out” testing in all GPs and emergency departments, a policy that has already been established in maternity care to great success: vertical transmission of HIV, from mother to child, has effectively been eradicated.

Extending the availability of PrEP into public spaces beyond sexual health clinics, such as primary care and pharmacies, is another key step that should be taken, says Gold.

Given the strength of England’s position – few countries as hard hit have come so close to eliminating transmission – there is concern that the momentum and funding needed to maintain the upper hand against HIV could fade away, especially as focus turns elsewhere in this post-Covid world. To ease off now, after the progress that has been made, would be heartbreaking – and tragic in consequence.

“All the elements are in the toolbox to enable us to get there,” says Green, of THT. “We just need to make sure we wield them in the right way over the next decade.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments