How ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’ got published

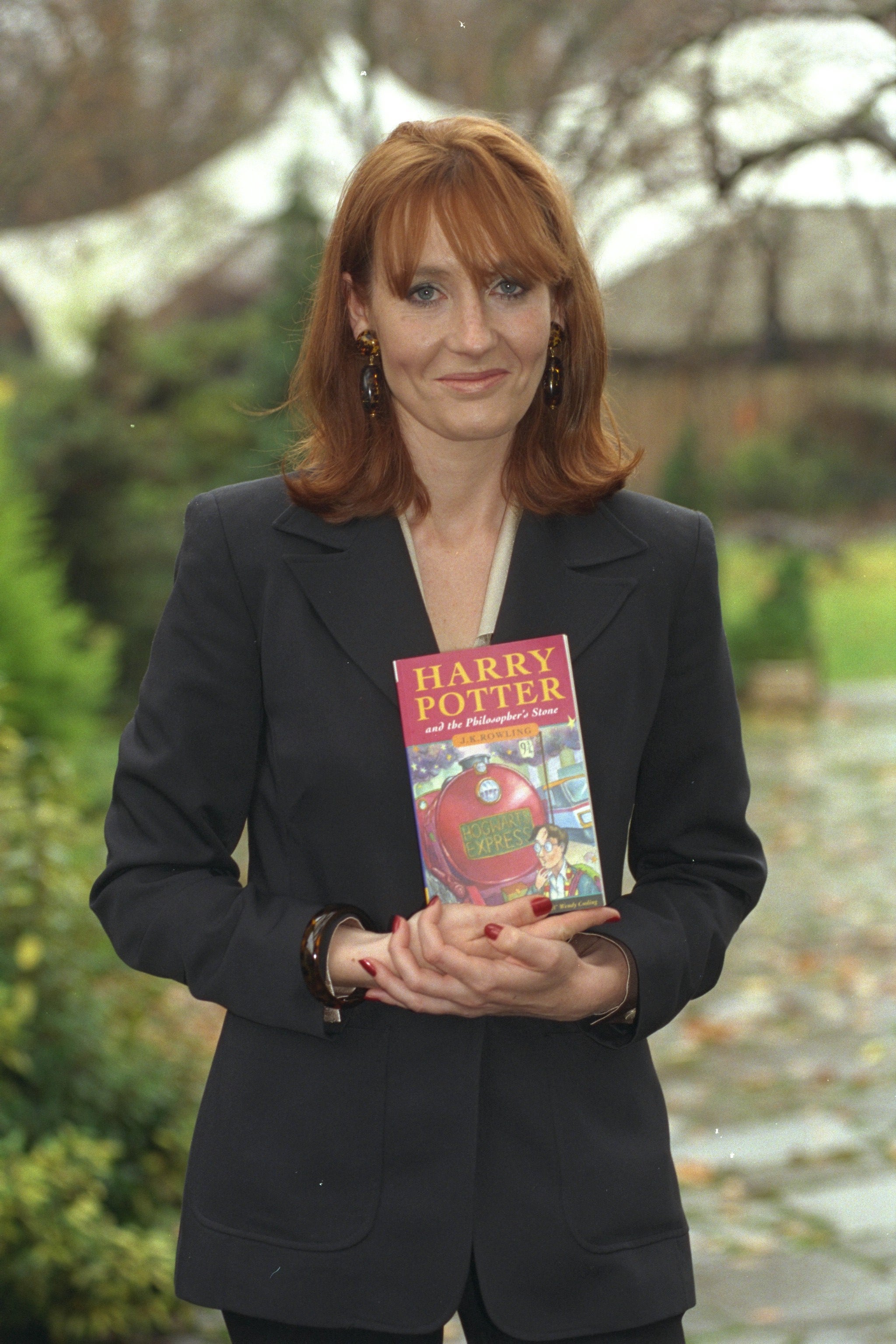

Twenty-five years ago Bloomsbury published the first book by the then-unknown Joanne Rowling. Sean Smith, who wrote a biography of the author, tells the story of how it happened

The first three chapters of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone went – unread – straight into the reject basket of manuscripts at the offices of the Christopher Little Literary Agency in Fulham, London. It was obviously a children’s book and the agency didn’t handle them because Little didn’t think they made any money.

Fortunately for millions of subsequent readers, Little’s personal assistant, Bryony Evans, would always have a flick through the discarded submissions just in case one grabbed her attention. She fished out the story of a boy wizard that, at this stage, consisted of a synopsis and three chapters which was a standard offering for most agents.

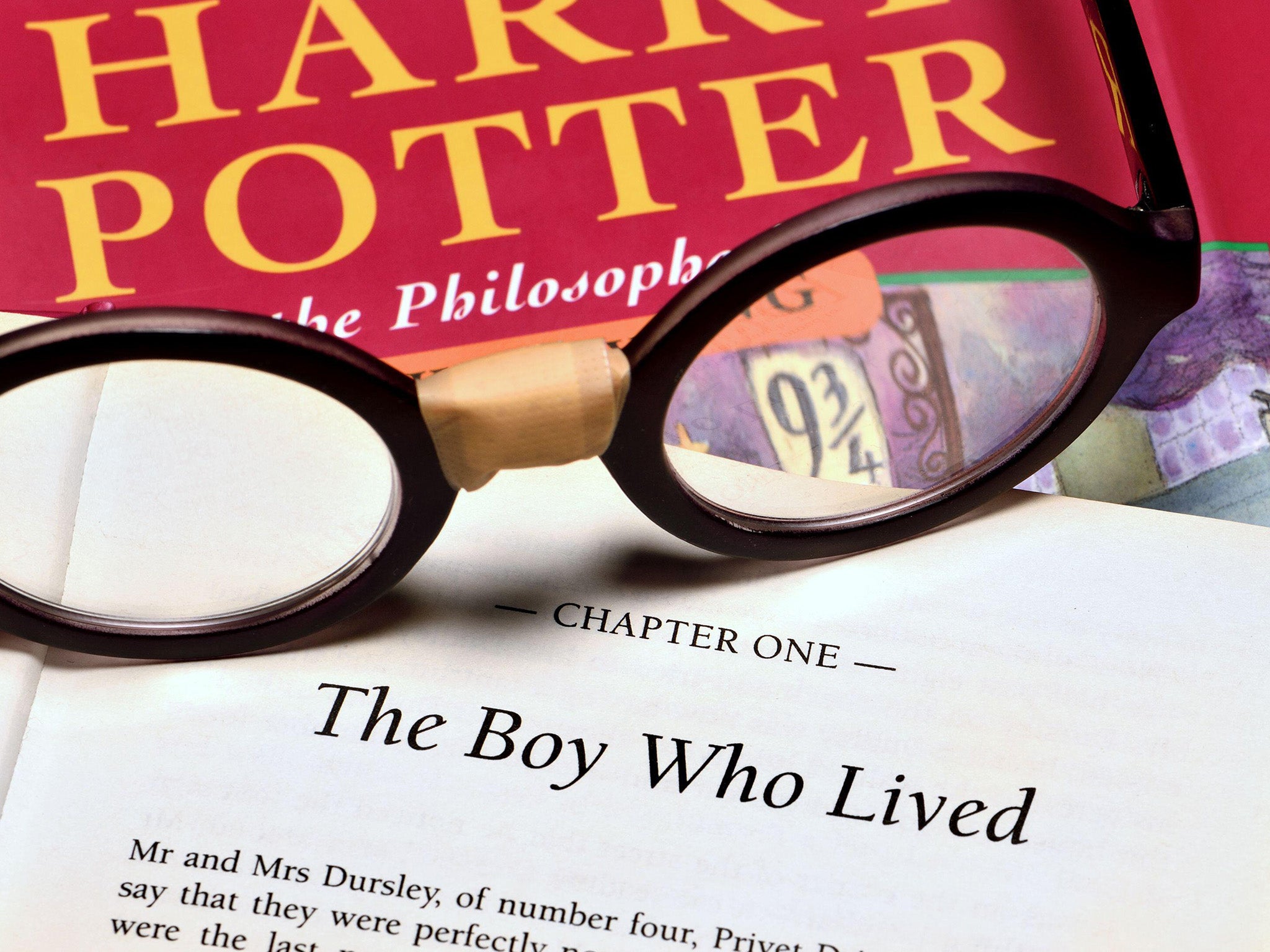

“The first thing I noticed was that there were illustrations with it,” says Evans. “There was one of Harry standing by a fireplace in the house of his ‘muggle’ guardians, the Dursleys, with his scruffy hair and a lightning scar on his forehead. I started reading the first chapter. The main thing that struck me, because I loved it, was the humour; when Mrs Dursley tells Mr Dursley that their son Dudley had learnt a new word – ‘Shan’t’.”

At the time the agency employed a young freelance reader, Fleur Howle, to look at unsolicited manuscripts and work with authors to make sure everything was of a high enough standard. Howle came in that afternoon and she too was impressed. At the end of the day, Evans said to Little, “can we send off for it? And he said ‘yes, whatever.’ And that was it.”

Evans wrote to the author, Joanne Rowling, on Little’s behalf asking for the rest of the manuscript. “It wasn’t a priority”, recalled Evans, but that was not how the single mother and fledgling writer saw things back in her small flat in Leith, the old port area just to the north of Edinburgh. She was dancing around the kitchen.

Rowling had assumed it was a rejection note. She had already tried one London agent who sent back a curt refusal and, annoyingly, kept hold of the special black file that she had used as part of a smart and, hopefully, professional package. She had expected Evans’s note to be the second no. But inside was a letter saying: “Thank you. We would be pleased to receive the balance of your manuscript on an exclusive basis.”

The writer, who had endured a wretched few years, would later reveal that “it was the best letter of my life. I read it eight times.”

The rest of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone dropped on the mat in Fulham within a week, just in case Little should change his mind. Rowling wasn’t to know that at this stage Little himself had yet to read a word of it. That would soon change.

Evans read it overnight and the next day, she passed it on enthusiastically to her boss who, to her surprise, did exactly the same. Neither felt the manuscript required much work although Evans wanted Neville Longbottom to be a little more developed because “he was such a lovely character.”

Little, meanwhile, was very keen on the game of Quidditch which he thought should play a bigger part. He thought it might be a good idea to put in the rules so the game would appeal more to boys.

Evans dropped Rowling a line and received a rapid response: “She had actually already written them so she just said ‘good’ and put them straight back in. She also enclosed an illustration of a Quidditch match; just a plain sheet of paper with the wizards on broomsticks interacting with each other.” After just three letters of communication, Evans was satisfied and was able to pass the business aspect over to Little who was very astute on such matters.

She was gazing dreamily out of the window of a train travelling from Manchester to London: imagining if this was a journey taking a boy who did not know he was a wizard to a wizard school

At the time, in 1996, Christopher Little was a man in his mid-fifties to whom the adjective “clubbable” could readily be applied. He was always charming and smartly dressed, usually in a pin-striped suit. He liked nothing better than to watch a Test match at Lord’s, for which he would sport his coveted MCC tie.

Like many successful men, it was a mistake to underestimate him. He was a tenacious businessman – the archetypal Rottweiler masquerading as a pedigree poodle, expert at exploiting fully every last ounce from a project. Rowling struck lucky when she picked his agency out of the Writers & Artists Yearbook in Edinburgh Central Library because she liked the name.

Up until taking on Rowling, the most famous name on his books was probably the thriller witter AJ Quinnell, who, coincidentally, was one of the few popular writers then to use initials rather than a first name. It was the pseudonym of Philip Nicholson who wrote his bestselling thrillers at his luxury villa on the Mediterranean island of Gozo, an existence a million miles away from the world of a financially-strapped single mum in Leith.

Rowling was thrilled beyond measure that an agent was taking an interest in the book that had been a positive part of her life since June 1990 when she first thought of the boy wizard. She was gazing dreamily out of the window of a train travelling from Manchester to London: imagining if this was a journey taking a boy who did not know he was a wizard to a wizard school.

Frustratingly, she had neither pen nor paper with her so just shut her eyes and thought of some of the characters who might be in it such as Ron Weasley and Hagrid; and the school itself would be a castle in Scotland. She didn’t have any names yet – that would come later – but in the coming months Harry Potter was a welcome diversion from the tedium of a life that seemed to be going nowhere.

On the following New Year’s Eve, her beloved mother Anne died after a 10-year struggle against “galloping” multiple sclerosis. Rowling was profoundly upset and would write what would arguably become the most moving chapter in the entire Harry Potter saga: “The Mirror of Erised” – a magical mirror in which the reflection you see is the image you most want to see in the whole world.

In Potter’s case, he sees his dead parents waving back at him. If Rowling had looked into the Mirror of Erised she would see her mother.

Evans, meanwhile, was in charge of sending Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone to publishers. Little had told her not to spend too much on photocopying; it can get quite expensive copying a 20-page manuscript a dozen times. Evans prepared three versions and stamped each one “Christopher Little Literary Agency”. The author’s by-line was “by Joanne Rowling.”

All Evans could now do was sit and keep her fingers crossed. Penguin was the first to turn it down. At Transworld, the woman who would normally have read it was off sick so it lay in a tray not getting read until Evans asked for it back so she could send that copy out again. In all 12 – yes 12 – turned down the chance to publish Harry Potter until a slightly dog-eared manuscript was sent to the offices of Bloomsbury in Soho Square.

The publishing house had been going for 10 years and had only recently started up a children’s book division under Barry Cunningham who had moved into editing from marketing and, like Little, had a flair for the business potential of a project.

Cunningham’s ambition was to publish books that “children would respond to” and he instantly found that quality in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone: “It was just terribly exciting. What struck me first was that the book came with a fully imagined set of characters. There was a complete sense of Jo knowing the characters and what would happen to them.”

The wheels of publishing turn slowly and Cunningham’s team could only get Harry Potter noticed by attaching a tube of Smarties to the manuscript when they sent it around to other editors. The bribe worked and after a month he was able to offer £1,500 for the book.

At the time, one other publisher, HarperCollins was still interested. Evans told them Bloomsbury had made an offer: “They came back and said, ‘we really like it but we’re not going to have enough time to put a bid together, so just go with the one you’ve got.’ So they dropped out which left us with Bloomsbury.”

Little sorted out the paperwork for Rowling, who could not have been more delighted. The sum was a small fortune to her; about £1,275 after the commission had been deducted. Bloomsbury made arrangements for her to come to London and meet everybody. She had to travel on a day return as she had to get back for Jessica, which meant 10 hours sitting on a train – most of which she spent working on the second Harry Potter book.

Rowling met Little and Cunningham for the first time at a little Soho brasserie. It was a great lunch. Cunningham recalled later, “I thought she was shy about herself but very confident and intense about the book and, most importantly, confident that children would like Harry. I knew she had a tough time since coming back from Portugal so I was very impressed with her dedication to the story. She just so understood growing up.”

At the end of lunch, Cunningham shook the hand of his latest author and told her: “You’ll never make any money out of children’s books, Jo.”

Rowling made her way home. The future multi-millionaire clambered wearily onto a number one bus from Princes Street in Edinburgh to Leith. Her biggest regret of a memorable day was that she did not meet Evans who had stayed behind to look after the office.

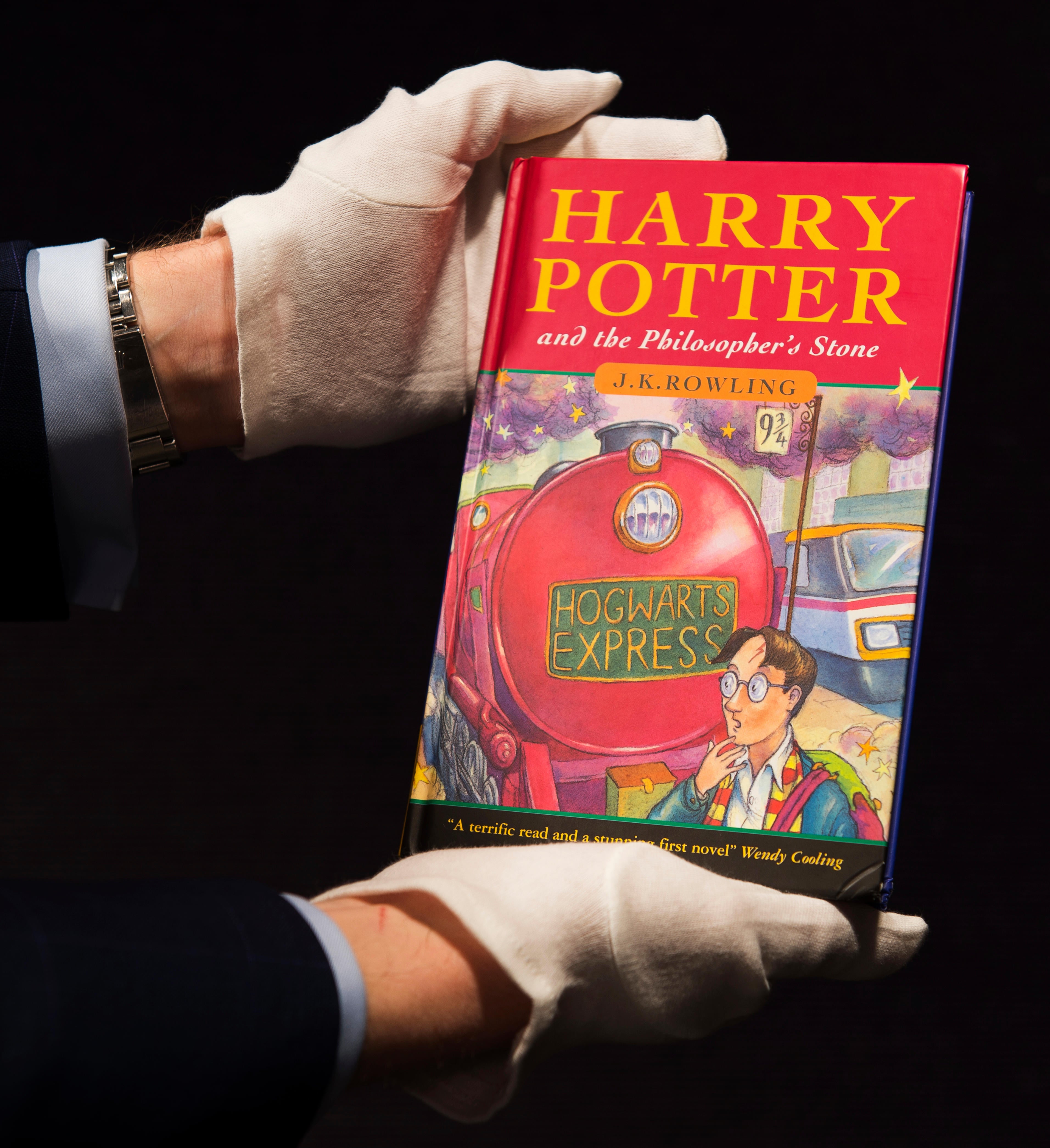

She still had a year to wait for the big day. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was published on 26 June 1997 in both hardback and paperback editions – seven, long, hard years since he first popped into her mind’s eye. The hardback print run was just 500 copies. Cunningham had commissioned the cover illustration personally. He wanted it to be approachable and charming – not too slick – but funny, reflecting the humour of Harry Potter.

Artist Thomas Taylor’s illustration of a schoolboy with thick round glasses and lightning bolt down his forehead standing in front of a train bearing the sign Hogwarts Express may rank as the most famous book jacket ever.

One obvious change from the original manuscript was that the by-line was now JK Rowling. Little had been concerned that whereas girls would read books by male authors, boys would not pick up a book if the author was a woman. He told Rowling that it would have to be initials plus surname. J Rowling did not seem substantial enough, JR Rowling sounded like a character from Dallas and JRR Rowling was verging on JRR Tolkein. Rowling did not have a second name so they put their heads together and came up with JK. It flowed off the tongue and Rowling like the idea of adding her grandmother’s name, Kathleen, to her own.

She set about mastering a new signature in case she had to sign a copy of her first book. She spent the whole of publication day walking proudly around Edinburgh with the book tucked under her arm, telling Cunningham that it was like “having a baby all over again”.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone has sold in excess of 120 million copies, making it one of the bestselling books of all time. Little, who died last year aged 79, amassed an estimated fortune of £50m from his association with the boy wizard. Cunningham founded the prestigious Chicken House publishing company, specialising in children’s fiction.

During the Cheltenham Literary Festival in October 1998, Rowling was signing books when she realised she was face to face for the very first time with Bryony Evans, who had changed her life that one freezing February morning in 1995. She signed a copy of her book: “To Bryony – who really did discover Harry Potter… JK Rowling.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks