The true story of Hare Krishna: Sex, drugs, The Beatles and 50 years of scandal

They’ve been dancing and chanting in Oxford Street for half a century. But what are they singing about and where did they come from? Ed Prideaux goes in search of the truth

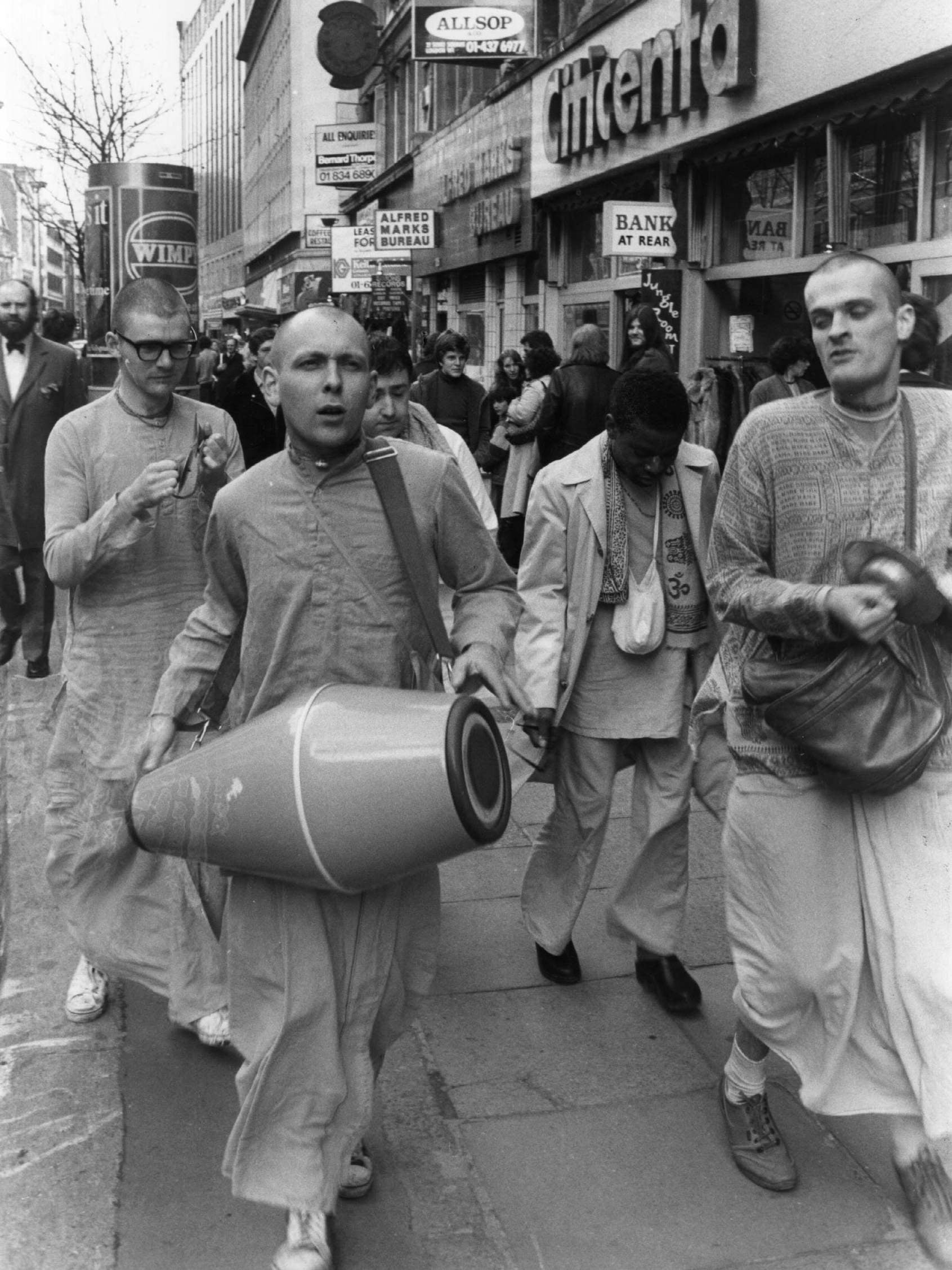

Fifty years ago this month, the Hare Krishna movement made London its permanent home. At the feet of their guru, the temple’s six founding members opened the doors of the group’s first-ever UK branch in a small property on Bury Place in Bloomsbury. In the half-century since, the Hare Krishna movement – otherwise known as ISKCON, or the International Society for Krishna Consciousness – has become one of the more curious and recognisable fixtures of British life.

You can usually hear them in the distance. Among the ambient noise of cars, chatter and traffic lights, their chants and beating drums stand out like a beam of saffron light. They dance, dart and circle, join arms, shout and sing, and call for strangers to join them. Bright-eyed devotees circle among the crowd, armed to the teeth with overspilling leaflets and mounds of books. Chanting, yoga, free food, meditation. Read this book: tell me what you think! The temple is always open!

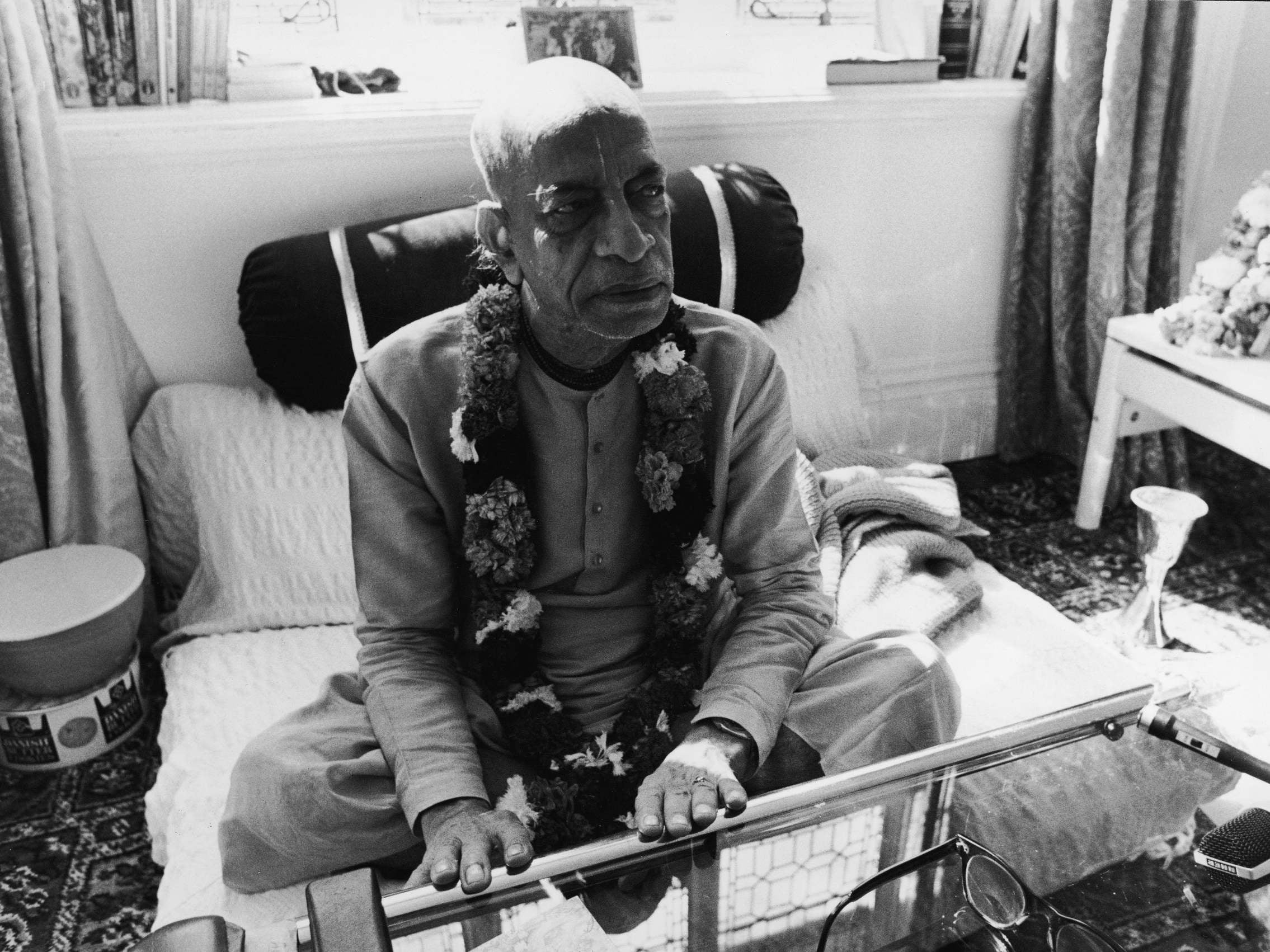

They always seem happy. And they’re a fairly inoffensive lot. However, what they’re singing about is something most of us don’t understand; and most of us know even less about how they got here. The movement begins and ends with one man. Despite having died more than 40 years ago, Swami Prabhupada, translated as “the one at whose feet masters sit” – is still the group’s central acarya, or spiritual master.

His life-like statue is one of two centrepieces in London’s Soho Temple. “Ji”, the crowd responds, as the Swami’s holy name is called. The guru sits and looks out to the temple dais, his body showered in wreaths, patterned cloth and even a Dior gift bag.

Born Abhay Charan De in 1896, Prabhupada seemed every inch the model British Indian. Commercial, “civilised” and loyal to the Queen, he attended a British school, took a wife, had children and ran his own successful pharmacy. But upon meeting his guru, Abhay was drawn increasingly away from the pitter-patter of everyday material life. He began spending more and more time thinking about Krishna, a flute-playing deity whom he and his guru deemed to be the original and most powerful member of the Hindu pantheon.

The Hare Krishnas follow two foundational texts in their worship: the Bhagavad-Gita and Srimad Bhagavatam. They believe that the material world – consisting of bodies, minds and our environments – is the creation of Maya, or illusion, and that our lots in life are the product of karma. While we may hold ourselves to be grounded in our names and occupations, our real identity, they claim, is an eternal spirit soul that lives in an infinite relationship of service to Krishna, or God.

Abhay’s guru instructed him to spread this message across the English-speaking world. After some years proselytising in theological pamphlets and promotional books, Abhay, now using the name Swami Prabhupada, boarded a one-way ship to New York in 1965. He was then 69. Upon his arrival, Prabhupada had only a scant suitcase of clothes, books and dry cereal, and a handful of cash equivalent to just $9. Prabhupada wouldn’t stay this way for long, however. Soon drawing the attention of New York’s burgeoning bohemian culture, he established Krishnas’ first temple in 1966 and laid the first brick of his eventual empire.

Allen Ginsberg, a famed Beatnik poet with an appetite for LSD and William Blake, became a regular attendee at Prabhupada’s lectures. Ginsberg found the group’s chanting sessions, in which they sing the names of Krishna in ceremonies called kirtans, a genuine source of religious ecstasy, and a worthy competitor to the dizzying heights of psychedelic drugs.

With Ginsberg’s evangelical endorsements, the Hare Krishnas began garnering some serious attention. Some of Prabhupada’s gang started making life-changing decisions, too. Convinced the Swami was a bona fide spiritual master, original members Michael and his girlfriend Jan became full-scale initiates. They adopted spiritual names, Mukunda and Janaki, and vowed to follow the group’s principles: no meat-eating, no gambling, no illicit sex and no intoxicants.

Vegetarianism and no gambling made some sense. The final two were a little harder for a hippie couple to swallow. No illicit sex meant a ban on all sex outside of producing children, and no intoxicants legislated against the use of alcohol, cannabis, hard drugs, tea, coffee and LSD. Prabhupada later declared that his mission was to kill the “demon crazy’’ LSD. He even viewed the drug and its reverence in the hippie culture as a fulfilment of holy prophecy, and a sign of the need for Krishna’s intervention on Earth. This didn’t stop his followers taking it, though, or at least from being inspired by the drug in becoming members.

A survey of the California temple in 1970 revealed that more than nine-tenths of its membership had smoked marijuana, and 85 per cent had tried LSD at least once. Many of them were regular users of both. Some felt that the psychedelic experience was a precondition for understanding Krishna consciousness. But for all their drug-addled faults, the hippies were good customers when it came to Krishna – and London was the next target.

Prabhupada sent three couples across the Atlantic in late-1968: Michael and Jan, Melanie and Sam, and Roger and Joan, who all had their own special spiritual names. Melanie was given the spiritual name of Malati Devi Dasi. The 74-year-old Malati has gone by her spiritual name for more than 50 years, and still serves as a senior member of the Governing Body Commission.

While the three couples gained a foothold on the British scene, Prabhupada was hard at work gaining support in cities across the US. He went to Seattle, Santa Fe, LA, Buffalo, Boston, Columbus and others, and even found time to help build a commune in Western Virginia, which was christened New Vrindaban, named after the ancient Indian city whence Krishna came.

By the time Prabhpuada died in 1977, New Vrindaban presented every image of a thriving intentional community. Led by one of the Swami’s hand-appointed disciples in Keith Ham, or Kirtananda Swami, the commune was set on more than 4,000 acres of lush southern grass, and seemed to house a truly inspiring alternative to modern life. Happy children, wandering cows and devotional service were the order of the day, and hundreds flocked in pilgrimages every year to emerge entirely different people.

More than anything, New Vrindaban embodied the sheer extent of Prabhupada’s victory. Against all the odds, he had already secured the movement’s next generation of devotees and gurus, and an international network of temples that was growing year-on-year. It looked like nothing could put the brakes on them.

The key to the Hare Krishnas’ success is a winning formula. As Malati explains: “It’s all about bridge-preaching: a kind of soft sell through free meals and friendly spiritual books, but they always have Krishna as the final product. For me, a bridge at one side means that it has to connect to the other side. So, I don’t care how you do it, but don’t forget you have to make the connection.”

It was the devotees’ trip to London, however, that proved the Swami’s greatest masterstroke. The London temple now distributes more than 700 free meals to local students every day, and more than 7,000 to the homeless each week. The UK branch even distributed 300,000 books last year, and comprises an assortment of 80 temples and 10,000 members.

The Beatles and George Harrison

But it wasn’t easy to start with. Just as Prabhupada had done two years before, the three couples struggled with poverty and unreliable work for much of 1968. And in between scrabbling for converts, selling books and securing a lease for their temple, the devotees had their sights set on the headquarters of Apple Corps, the new Beatles enterprise, on Savile Row. “The Beatles were the target,” Malati says. “They were the most famous folks on the face of the Earth at the time.”

“If they chanted, the whole world would chant. And that was our strategic plan.”

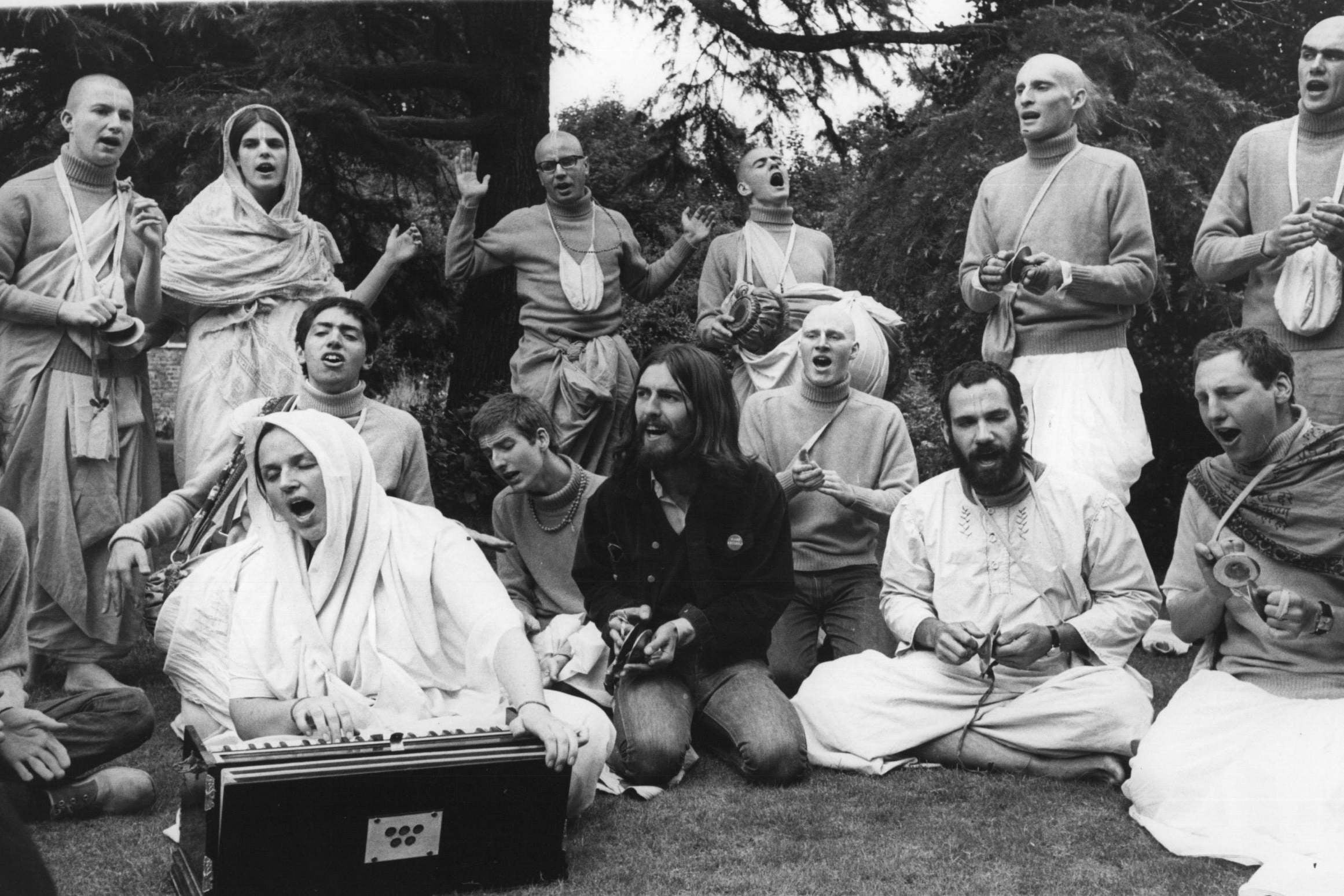

They sent the group home-baked apple pies. They chanted regularly on the steps outside the offices and hoped that Krishna would grant them a meeting. And after arranging some time through Peter Asher, a Beatles’ associate and one-third of Peter, Paul and Mary, George Harrison finally met the devotees face-to-face.

“Hare Krishna. Where have you been? I’ve been waiting to meet you,” he said.

“George was the most interested,” Malati reflects. “[He] emerged as the most likely candidate quite quickly. John Lennon had interest. He expressed it, but his wife, Yoko Ono, was not… And that put a damper on his whole enthusiasm.”

Known in the headlines as The Quiet One, Harrison didn’t take long to give the Krishnas a wholehearted embrace. He convinced the devotees to spread the word with a recording, and secured a session date at EMI Abbey Road Studios in the summer of 1969. Watched over by a curious Paul and Linda in the control booth, George and the devotees sat on the floor amid a tangled sea of microphones and leads. George was focused, Syamasundar (Sam) recalls, with the group making swift recordings of chanting choirs, wobbly guitar and psychedelic harmonium.

By the session’s end, they seemed to have accomplished something quite impossible: George and the Radha Krishna Temple had recorded an ancient Vedic mantra recitation that may actually work as a pop single. Apple soon slated the release for late the following month. At a press conference announcing the new record, George Harrison gave the Hare Krishnas his most singular endorsement yet. “I’m completely at ease now. I know everything’s alright and getting better. I just get happier and happier,” he declared. “The thing they [the Hare Krishnas] have in common is to get back to God and to get consciousness... I never stop chanting the Krishna mantra.”

The media couldn’t get enough. Hippies who’d gone the whole mile and become shaven-headed monks, let alone sitting with George Harrison, was just too good a picture to miss. The attention didn’t stop there, either. In perhaps one of the strangest chapters in British chart history, the Hare Krishna Mantra single, backed by a B-side recording of Prayers To The Spiritual Masters, went on to sell 70,000 copies in its first day alone. It was the fastest-selling record of any non-Beatles Apple release to date and peaked at number 12. It was also becoming popular internationally. It hit the top 10 in Holland, Germany, France, Sweden and Australia, and even secured the number one spot in communist Yugoslavia.

Towards the end of 1970, Harrison released All Things Must Pass, a solo album that stayed on the album charts for eight weeks straight. Near-enough every song on the album was either inspired by or endorsing of George’s newfound Krishna Consciousness, and the album’s lead single, “My Sweet Lord”, proved the group’s biggest PR coup yet. It featured the Hare Krishna mantra and a traditional guru prayer under pop-friendly chart treatment, and garnered over 5 million sales by 1978. Krishna was everywhere. You couldn’t get away.

It was the Hare Krishnas’ “strategic plan” to meet The Beatles – but their greatest accomplishment may yet have stored the seeds for something much darker down the line.

Krishna in crisis

On his death in 1977, Prabhupada’s 11 appointed gurus found themselves with more responsibility than they’d bargained for. Malati, who has been a governor on the movement’s parliamentary Governing Body Commission (GBC) since the 1970s, recalls that “it was a very bewildering, complex time”, and a mood of panic seemed to pervade every layer of the organisation. They’d simply got too big.

Malati was just 22 when she became initiated. And she was only in her early thirties when she was thrust into overseeing the spiritual journeys of tens of thousands of souls worldwide. Turned on by George and The Beatles connection, scores of new wide-eyed devotees were joining up every year intent on nirvana.

“They found themselves with such an amount of power,’’ one London devotee recalls. “And power gets in your mind. You become crazy. You become mad. And they fall down.”

The New Vrindaban community in the US, which had seemed to project a scene of almost Edenic attraction, had instead become home to systematic sexual abuse, brainwashing and racketeering. Allegations began emerging in the 1980s that the community’s leadership, in particular its central guru Keith Ham was preying on children and vulnerable devotees for sex.

Millions in donated funds were being misappropriated. The guru’s gang of fanatic devotees acted under his every beck and call. One outsider devotee, Chuck St Denis was murdered on the guru’s orders for improper monastic conduct and, more likely, for seeking the recompense of an $80,000 sum he had lent the master. St Denis was buried by a stream on the estate and his body dissolved in acid.

Steven Bryant had been lodging serious complaints about the commune for years. Regarded as a crank by law enforcement, Bryant, 33, was shot in the head while sitting in his van by an assassin. New Vrindaban wasn’t even the start of the Krishnas’ troubles. Suspicions began hanging over the group in 1979, when a ring of Californian devotees were caught trafficking heroin and laundering the earnings in an investment firm. Another of the 11 appointed gurus was caught stockpiling weapons.

Malati offers a mixed reflection on the time. “Everybody knows we went through the big child abuse issue. We had no clue this was going on… In general, the regular public had no idea about child abuse. It was ‘hush, hush’.”

“In the early 1980s, the headlines were about Aids,” she explains. “The next headlines, in the mid-Eighties, were about child abuse… There was some mention {of child abuse at the commune}, but we didn’t know what we were hearing. It took some time. It was a learning curve.”

Keith Ham and the group’s other rogue gurus were kicked out in disrepute. The New Vrindaban leader was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment and died in 2011, with a small surviving band of fanatics in India still falling at his feet.

The group’s catalytic growth created some other problems, too. Many were initiated without being of sound mind to do so, and the volume of new devotees made due diligence and real quality control a demanding task for administrators. And since the original initiates were drawn from the hippie movement, germs of risk were part and parcel of the group from its foundation.

One devotee, James Edward Immel, was one of the Hare Krishnas’ original signups. He had been a follower of Dr Timothy Leary (Leary being a countercultural psychologist who promoted psychedelic drugs) and joined the doctor in expounding the benefits of LSD.

He was sent by the GBC to manage the UK branch, and soon secured Croome Court, a sizeable country estate in Worcestershire. Budgets in the hundreds of thousands were expended on refurbishments, and the estate was transformed into a bustling temple and education centre for new initiates.

Immel drew a lot of attention. The intensity and rapture of his chanting sessions were a source of bewilderment and admiration in equal measure. They could last up to 12 hours and frequently ended with him rolling on the floor, laughing and hysterically crying. He lectured zealously about divine love and maintained that a flow of Krishna’s energy was descending upon him.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, the guru was still imbibing large amounts of LSD, and the GBC was now concerned that he was in the throes of a drug-induced psychosis. After ordering him to take full renunciation in 1980, Jayatirtha parted ways with ISKCON two years later. He founded a splinter group in London and attracted a devoted following, with intense LSD-fuelled chanting sessions their MO for reaching Godhead. One of his most fanatical disciples, Anthony Kiernan, had long-struggled with symptoms of mental illness, and he even considered the guru to be the modern reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

Kiernan changed his mind, however. He was convinced that the guru was instead the anti-Christ and had to save the world. He took a blade to Jayatirtha’s neck and decapitated him. Kiernan was caught and arrested while still caked in his Master’s own blood. “ISKCON LSD-GURU BEHEADED BY HIS OWN DISCIPLE,” the front page of the Evening Standard read. The Krishnas’ already-souring reputation only seemed to take a further blow.

With stories like these, it’s easy to assume that the Hare Krishnas are a classic cult. They deny the outside world, maintain devotion to a charismatic leader, and have contained some unfortunate abuses of power and the law. They’ve been called as much by anti-cult organisations like The Cult Education Institute and the Freedom of Mind Resource Centre.

But for Maharshi Vyas, a scholar of religion at The University of California Santa Barbara, calling ISKCON a cult is a fruitless exercise. “With the perception of a religious tradition,” he explains, “it all depends on who you ask.”

“By using the word ‘cult’, you are immediately othering that religious group and making it impossible, to some extent, to understand them.” Indeed, while the Hare Krishnas’ organisational structures – in particular its systems of gurus and “disciplic succession”, whereby authority is transferred from guru to disciple in a kind of religious monarchy – may seem cultish to western eyes, they’re common elements of the Hindu tradition.

Vyas describes a very popular prayer in Sanskrit that is recited by many Hindus (and was even included in Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord”) that considers the guru to be equivalent to Brahma, Vishnu and Maheshwara, or Shiva, the Hindu trinity of the creator, preserver and destroyer Gods.

“You can’t say that when someone is following some guru, they are doing it simply because of blind faith or that they have nothing better to do in their lives,” he adds. “Western preconceptions of religion assume that people are simply stupid when they follow their guru.”

And if some organisational abuse does occur, “it’s those specific individuals who should be held responsible and not the entire organisation. The organisation consists of a lot of ordinary practitioners. They go there because they enjoy being there. They enjoy the community and those particular forms of worship.”

Hare Krishnas’s UK branch now encompasses more than 10,000 lay members. On walking into the Soho Temple today, where the group is busy celebrating the final act of its nine-day 50th anniversary festival, the legacy of Prabhupada is plain to see. The UK branch took more than £11.4m in endowments last year and oversees a portfolio of around £35m in assets.

The temple has a well-run bureaucracy of PR, secretaries, managers and a full-time kitchen staff for its restaurant, Govinda’s. It’s packed to the brim with followers of all ages, shapes and sizes. There’s even an extra room to watch gurus’ speeches on a televised livelink. It’s an easy stereotype to make, but the Hare Krishnas are too broad a church to consider a bunch of hippies anymore. I joined the group for a sankirtan, or public chanting session, around Oxford Street and Leicester Square, and was struck by the sheer diversity of its membership.

One believer is a fund manager and oil consultant who works with governments in the emerging world. Another is a Croatian, Prema Harinam, who joined up after fleeing the horrors of the Serbo-Croat war. There’s the 27-year-old from Bologna, Shyam Govinda, who studied part of his master’s in International Relations at Oxford and is now a full renunciate. Or consider Russell, the 48-year-old who credits Krishna Consciousness with helping him to kick cocaine addiction. And if that isn’t enough, two Russian devotees were on the march, too, having become devotees in the last days of the Soviet Union.

Not everyone is a convert or a westerner, either. Gopal and Shyam, from Uruguay and south London, were born into the movement. And Malati describes how “Indians have enthusiastically embraced Krishna Consciousness in a process referred to in the GBC as the Hinduisation of ISKCON. “In other words, how many western people do you find in the temple?... It was overwhelmingly western [then]… And now we’re standing as the minority.”

Most are optimistic about ISKCON’s future. Shyam Govinda believes that there may be another spiritual revolution along the lines of the 1960s. With our culture’s increasing adoption of yoga, veganism and meditation, it’s not an assumption that can be dismissed too easily. Indeed, Malati claims that ISKCON is “offering the highest form of yoga: Bhakti yoga, of the Supreme Personality of Godhead”.

“Even a child can chant. Even a dog can chant.”

The increasing miseries of social media, technology and old-age loneliness are taking their toll, too. “The degree of suffering that is going on now is so obvious,” Malati says. “And when little children are committing suicide [as with the 2017 death of Molly Russell], that lets you know that there is something very wrong with society.”

ISKCON isn’t totally immune to the modern world, either. Despite having just two women on the GBC, the 35-strong commission recently declared that women can become full initiating gurus, finalising a process that had been delayed for years by conservative opposition.

Whatever the future of the Hare Krishnas, though, there’s one thing for sure. In another 50 years, there’ll still be nothing like them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks