On the banality of evil: Hannah Arendt, philosophy and Nazism

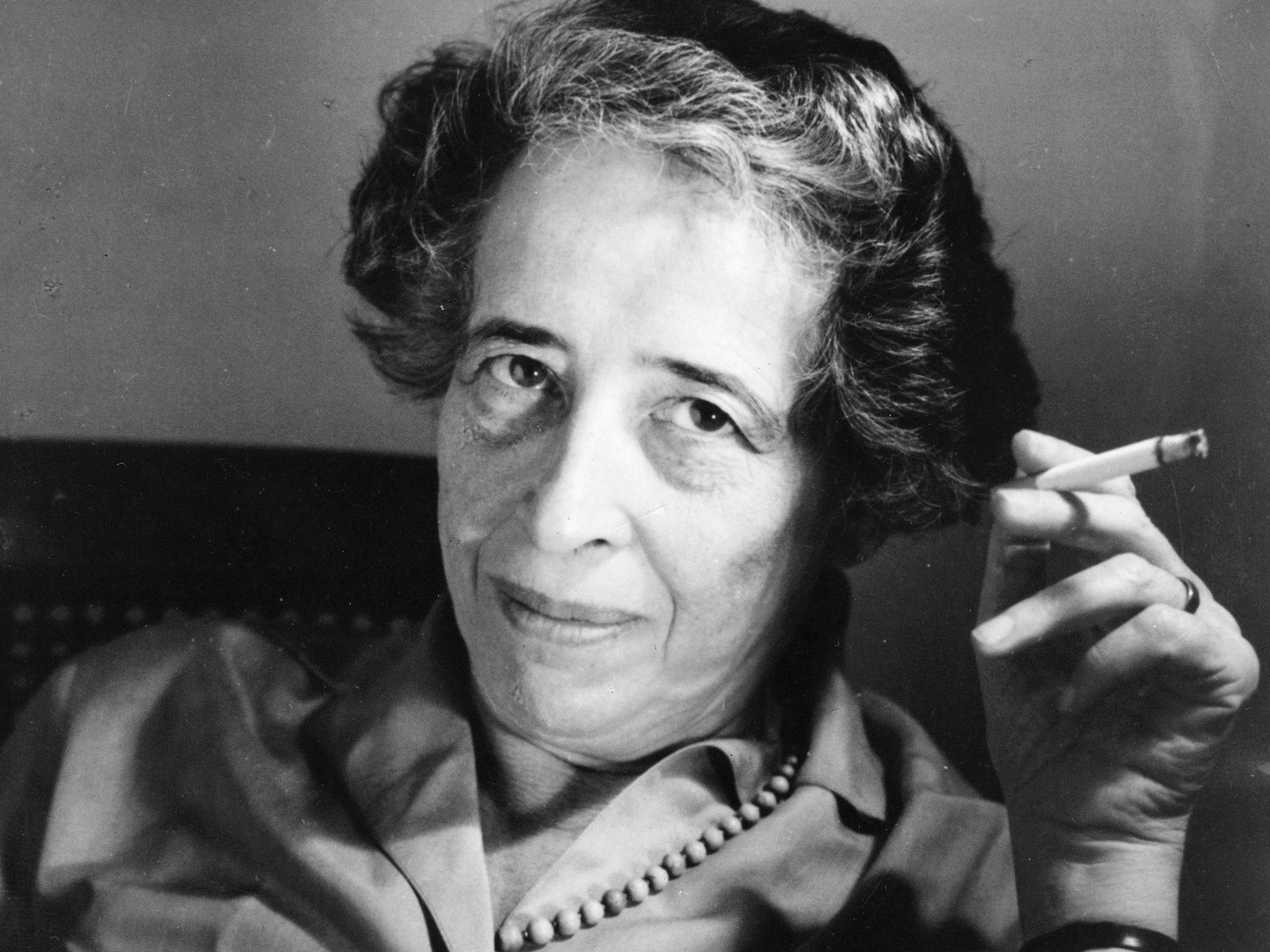

Hannah Arendt’s name will forever be associated with the disenchantment and de-romanticising of evil, writes Chris Horrie, and this summer sees the anniversary of two of her works

This summer marks respectively the 60th and 70th anniversaries of the two main works of the 20th century political philosopher Hannah Arendt. Although she is usually described as German Jewish, since she was born into a secular Jewish family in Hannover at the start of the 20th century, she described her nationality as “refugee”. In the age of industrial modernity the refugee had emerged as a “new type of person”, defined by the fate of being “placed in concentration camps by foes, and of being placed in internment camps by friends”, as she put it.

The first of these works is On the Origins of Totalitarianism, published in 1951, as an extension of a study of the history of anti-semitism which she had begun before the second world war. At the time the term ‘totalitarian’ was used fairly loosely to describe any sort of dictatorial regime. Arendt’s use of the term is more precise and more profound. Throughout history tyrants of one sort of another have sought to physically subdue or enslave populations. The essence of totalitarianism, as practised in both Nazi Germany and in the Soviet Union was to enslave the mind, to create perfectly obedient human robots or “marionettes” as Arendt described officials of the Nazi SS or the Soviet KGB, while deporting or murdering those who would not or could not conform (ethnic minorities, those stricken by conscience, dissidents, resisters, romantics and outsiders) on an industrial scale. Once the conformist majority had learned this lesson and the non-conforming minority eliminated, then a new golden age would arrive and last forever. Arendt was struck by the way in which many of the ‘operatives’ of totalitarian regimes believed themselves to be good and morally upright utopians, who had been working in the interests of humanity as a whole, including their victims.

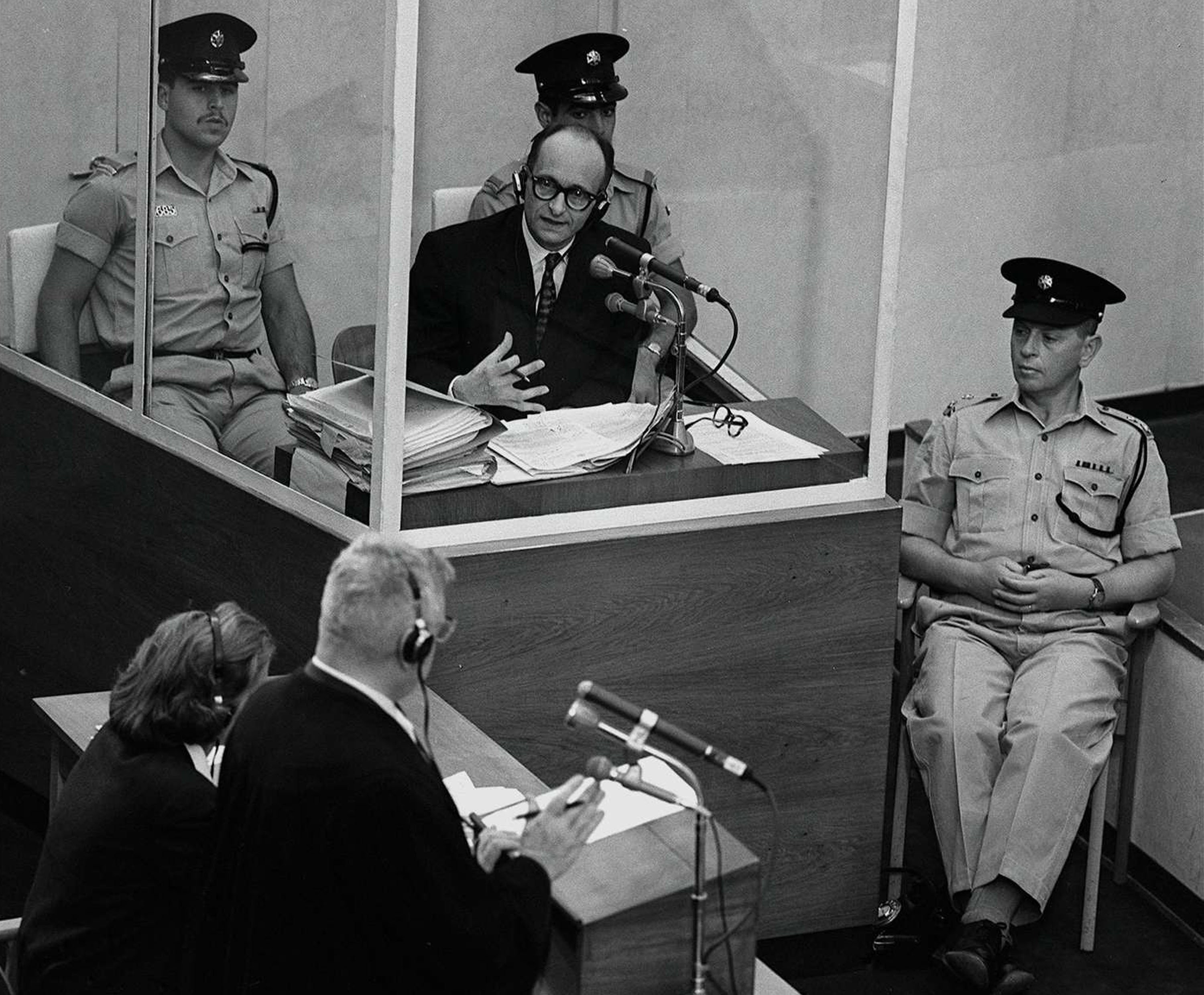

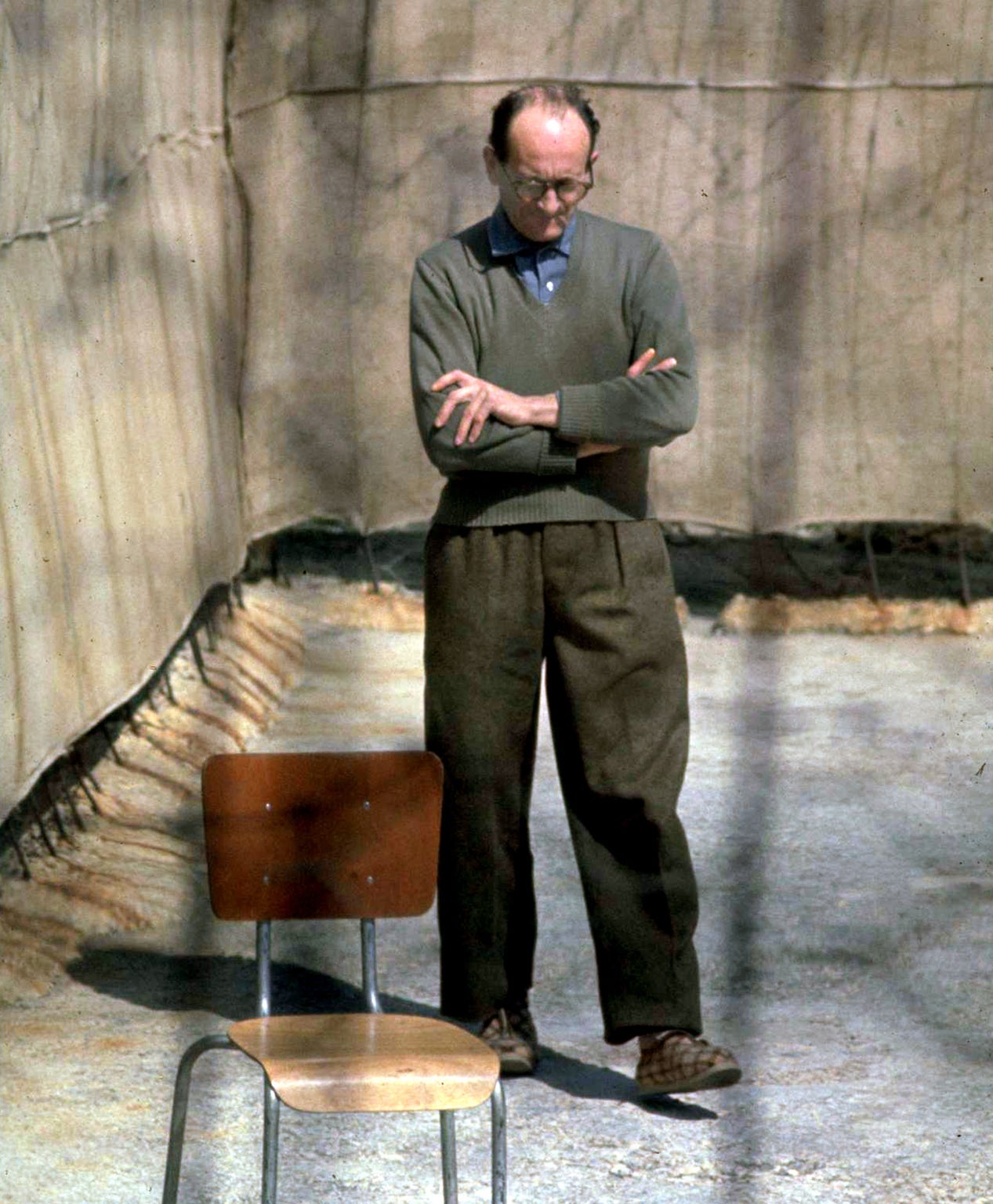

Thus the second of Arendt’s works with an anniversary this summer is Eichmann in Jerusalem, which is an account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official primarily responsible for organising the deportation of millions of Jews, Gypsies and others to the Auschwitz ‘death factory’ where they were murdered or worked to death. Eichmann had in fact escaped to Argentina after the war where he had been abducted by special forces deployed by the newly formed state of Israel and brought to face televised trial in Jerusalem.

During the proceedings Eichmann complained that he had never personally killed anyone, had not broken any law that was in place during the Nazi period and generally exuded the arms-crossed air of an indignant bank clerk falsely accused of having his fingers in the till. Further, Eichmann claimed that throughout his career he had been helping Jews to voluntarily emigrate from first his native Austria and then Germany where it was true they faced hostility and discrimination. But that was not his fault. Anti-semitism was a centuries old problem and he was merely trying to bring the problem to an end. Far from being motivated by hatred of Jews, Eichmann maintained, he was trying to help them. He was the author of a detailed scheme to re-settle central Europe’s Jews in the French African island colony of Madagascar.

The plan depended on using the British merchant navy to transport the settlers which Eichmann believed would be available after the surrender of the British in 1941. When the British did not surrender, the plan was abandoned. Plan B was to ‘encourage’ Jews to migrate to occupied Poland and Russia, or further east into Siberia as soon as it was liberated from Soviet rule. When Germany started losing on the Russian front as well, there was really nowhere to put the Jews and so Hitler had decided to kill them. Eichmann told the court that he had a duty to obey the orders. He had after all sworn an oath to do so. It would have been immoral not to follow the orders and organise the mass transportation of Jews and others to camps. After that if anyone was guilty it was Hitler. And he was dead now, conveniently enough.

The title and Arendt’s treatment of the subject matter was seen as scandalous at the time, and the banality tag, attached to the Holocaust, is the foundation of her contemporary significance

Throughout the trial Eichmann had remained calm, with the mildly irritated and exasperated demeanour of one wrongly and unfairly accused. More recent scholarship has shown that Eichmann was more ideologically driven than he let on, and that his naive, boring, jobsworth personae was merely part of his defence. But during his trial the mask slipped only once – when he was presented by a note in his own handwriting saying that he would go to his grave delighted that he had played a role in the elimination of millions of Germany’s enemies. He wriggled out of this by saying he was referring to casualties inflicted by Germany on the Red Army of Communist Russia – a perfectly respectable moral position to hold in the cold war 1950s - and not to Jews or other concentration camp victims as such. He and his supporters would whinge about the nature of his abduction from Argentina where he had a perfectly happy and unremarkable suburban life as a sales executive for Mercedes Benz (who else). Far from the raving fanatical sadist of the Nazi stereotype, Eichmann presented himself as an unremarkable, time-serving bureaucrat, loving husband, caring parent and family man who was ‘only doing his job’.

Thus Arendt later added a subtitle to a collection of her New Yorker reports on the trial, published as a book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. The title and Arendt’s treatment of the subject matter was seen as scandalous at the time, and the banality tag, attached to the holocaust, is the foundation of her contemporary significance. She was widely accused of either sympathising with Eichmann, or at the very least of failing to take into account the feelings of concentration camp survivors, or of the still grieving relatives of the victims. Arendt had startled the world with the idea the commission of murderous cruelty and evil was banal and ubiquitous in modern industrial societies. Evil was not the result of evil men seized by a type of moral madness or perhaps inspired by the devil or evil spirits. That was the pre-modern mindset, the religious moral system which dealt with people as either saints or sinners, animated by mysterious otherworldly forces. But modern man had moved beyond good and evil, as German philosophers liked to say. The commission of evil acts was not inevitable or ‘radical’ (in the sense of fundamental) Arendt argued, and was rarely the sole moral responsibility of any particular person. It was more like a fungus which spread easily and was ever present just below the surface. It could flare up suddenly and unpredictably in societies which, in their decay, had turned to totalitarianism.

Arendt faced criticism, especially from the many enthusiastic supporters of the creation of the news state of Israel as a place of safety for persecuted Jews. The New York intellectual Norman Podhoretz, himself from a family of Jewish refugees, wrote a lengthy and scathing review of Eichmann in Jerusalem insisting that, yes, there really was such a thing as unique and fundamental evil and irredeemable guilt, and that was represented by the Nazi regime. Likewise the victims of Nazism were necessarily innocent, despite Arendt’s discussion of collaboration of some Jewish community leaders in plans for mass migration from Germany. The genuine ‘fungus’ of the modern age was moral relativism which refused to judge, and strove to find evidence of innocence in the guilty, and guilt in the innocent. The argument in Arendt’s book, he wrote, would be “persuasive to the sophisticated modern sensibility - the sensibility that has been trained by Dostoevsky and Freud, by Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, by Eliot and Yeats, to see moral ambiguity everywhere, to be bored by melodrama, to distrust the idea of innocence, to be sceptical of rhetorical appeals to Justice.” Podhoretz concluded: “The Nazis destroyed a third of the Jewish people. In the name of all that is humane, will the remnant never let up on itself?”

The lives of Hannah Arendt and Adolph Eichmann were strangely intertwined. They were born in the same year, 1906, at the start of the murderous 20th century. Eichmann grew up in Austria, was involved in right-wing Catholic movements and joined the Nazi party in the early 1930s. He had worked as a day labourer and an oil salesman in Vienna until 1933 when the Nazi party was banned in Austria after Hitler seized power. Suddenly jobless as result of his party membership Eichmann got a job with the Austrian branch of the Nazi party temporarily exiled in Bavaria. After the German annexation of Austria, Eichmann returned to Vienna and developed a career in the logistics of rounding up Jews first in Austria, and then Czechoslovakia. Eichmann was so successful in this role that by 1940 he had become head of the Nazi state department responsible for the sending Jews to concentration camps throughout German occupied Europe, including France.

One of the Jews Eichmann should have ‘processed’ as a matter of priority was Hannah Arendt, a brilliant if somewhat obscure philosophy teacher who, in her early life, had tried to stay as far away from politics as possible. Arendt’s original interests had been in theology and ethics, especially the religious teachings of St Augustine, the 4th century founder of much of Catholic theology, especially the emphasis on the doctrine of original sin, and the necessity for redemption through love, however that might be defined. Her studies brought her under the sway of the philosopher Martin Heidegger at the University of Marburg who shared or even directed her interests. Heidegger had rejected the scientific liberalism and humanism which had dominated universities in Europe and America in the modern age. He emphasised the importance of the darker tones of pre-modern and religious thinking. Modernism and technology had been a disaster resulting in mechanised warfare, ‘inauthentic’ mass communication, and rootless life in overpopulated cities. In the modern world people had lost contact with their ‘Dasein’ – their natural spirit of prompted, Heidegger believed, by the central and unique human attributed: the contemplation of a terrifying eternity of death.

The project of intellectuals, Heidegger thought, was to roll back the tide of modernism. University philosophy departments had long rejected ‘medieval’ philosophy such as that of St Augustine. But this was a mistake, Heidegger taught. Materialistic modernity was not the answer to the human problems, it was the cause of them. The answer was to sweep away all forms of liberalism in the universities and to eventually return to a more ‘authentic’ rural way of life, of ‘Heimat’ (roughly ‘blood and soil’ or ‘you are what you eat’). Heidegger himself lived in a simple stone hut on the side of a mountain without electricity, with or without realisation that the population of entire cities and regions would have to be removed if everyone were to enjoy the Good Life in this way. In the realm of thought the tedious and money-grubbing logic chopping and supposedly value-free analysis of Anglo-American ‘positivism’ had to be replaced with emotion, intuition, instinct and blind faith. In other words Martin Heidegger was a dedicated Nazi. And astoundingly Heidegger was not merely Arendt’s teacher, he was her lover. The two had an affair, surely the most bizarre relationship in the history of modern intellectual life.

Arendt followed Heidegger from Marburg to the University of Freiberg, where Heidegger had secured the chair of the Philosophy department – a significant promotion. The appointment had taken place at the behest of Edmund Husserl, the liberal-minded outgoing professor of phenomology. In 1933, a few weeks after Hitler assumed power in Berlin, Heidegger was again promoted to become rector in charge of the entire university. The previous rector has refused to display Nazi symbols and posters around the campus and had been sacked. Heidegger took his place, an appointment personally approved by Hitler. One of his first acts was as rector to participate or at least condone the removal of Jewish professors from the university, including his erstwhile patron Husserl. Heidegger’s commencement address as rector was to become one of the classic and foundational documents of the Nazi regime. He called for ‘the re-assertion of the German University’, supervised a purge and made remaining professors sign an oath of allegiance to the National Socialist state. A month after Heidegger’s appointment German universities were require to take part in ritualised night-time book burning ceremonies in which the literary and scientific works of Jews as well as many others, regardless of subject matter, were committed to the flames.

Arendt later claimed that she had at first purposefully ignored Heidegger’s Nazism, believing that philosophy and politics were entirely different spheres, and that anyway intellectuals had not merely the right but the duty to examine lines of thought which might be uncomfortable and even horrifying in their implications. But she had been shaken by the treatment of Husserl, and for a while blamed Heidegger for his premature death in enforced retirement, even describing her former lover as Husserl’s “murderer”. Arendt later withdrew the murderer allegation, and claimed instead that the suspension of all civil rights in Germany after the Reichstag Fire in 1933 had forced her into the political sphere. The relationship with Heidegger ended, at least temporarily, though she continued to support some aspects of his anti-modernist philosophy, and gave credence, post-war, to Heidegger’s implausible, Eichmann-like claim that his support for the Nazi Party had been incidental to his main work as an academic.

Arendt received a far from warm welcome in New York in 1940. In the previous year 300,000 German Jews had applied for asylum in the United States, but fewer than one in four applications were successful

Arendt’s political activities in pre-war Nazi Germany were decidedly low-key. She used her skill as a researcher and vast reading of the history of religion to conduct research into the roots and causes of anti-semitism, at the behest of a German Jewish welfare organisation, while continuing her main research into Saint Augustine and what was still thought of as the backwater of Dark Age philosophy. In 1933 Arendt was arrested by the Gestapo on charges of conducting illegal and subversive research. She was released after a few days of interrogation but decided that Germany was no longer a safe place for herself or for any Jew, and so she fled to Paris as a refugee. There she continued her research into the roots of anti-semitism, which was to form the basis of the first part of On the Origins of Totalitarianism. She also worked for Jewish youth organisation which prepared German and other Jewish orphans for illegal emigration to Palestine where she hoped some sort of new Jewish community could be established as a place of safety for European Jews, should that be needed, despite the opposition of the British colonial authorities which controlled the area at the time. Eichmann himself had negotiated with both Jewish leaders and with Arab-Palestinian nationalists to allow limited Jewish migration from Germany as a contribution to the process of making Europe ‘Jew Free’. German law in the Nazi period allowed for migration, but only on condition that Jewish capital and property remained in Germany and to be confiscated by the state.

In 1937 Arendt in exile in Paris was stripped of her German citizen and given the status of a traitor and an enemy alien in exile, in effect a death sentence in absentia. The following year she was assessed as a stateless individual and potential security threat by the French authorities. She was sent to a French run refugee internment camp in Gurs, near the Spanish boarder in South West France, originally established to cope with streams of refugees from the Spanish civil war and the fascist military regime installed by Germany’s ally, General Franco. After the German conquest of France in 1940 administration of the camp was transferred from France to Germany, and to Eichmann’s department. Realising that this meant certain death Arendt managed to exploit confusion during the handover and escaped from the camp, taking with her as she later wrote, only her toothbrush. She made her way across Spain and Portugal and finally made it to New York late in 1940. The majority of the 7,000 internees Arendt left behind in Gurs either died in the insanitary conditions of the camp or were later transferred, under the overall supervision of Eichmann, to Auschwitz. It was the narrowest of narrow escapes. Arendt always maintained that she had been extremely lucky throughout her life.

Arendt received a far from warm welcome in New York in 1940. In the previous year 300,000 German Jews had applied for asylum in the United States, but fewer than one in four applications were successful. The tone had been set in 1939 by the fate of the 900 German Jewish refugees on board the civilian transport ship St Louis who had been turned away off the US coast. They were forced to return to Europe and the majority subsequently died in concentration camps. From this point onwards, and although she spent the rest of her life until her death from a heart attack in 1975, Arendt would often claim her identity was not first and foremost as a Jew, German or American, but as a refugee – part of a ‘nation’ which, if it were to be recognised as such, has grown since her day to become the twentieth largest country in the world, with some 80 million people – already larger than the population of the UK or Germany and growing. More than half of the world’s refugees are under 18, and many are very young children.

Arendt was probably helped by the fact that she had arrived in the USA alone, and that she had done her research and administrative work for Jewish welfare organisations in Germany and France. Similar organisations in the US were willing to sponsor her. On the other hand she spoke virtually no English at the time. Her academic credentials were not recognised, and she did not secure a university position until 1952. Instead she worked throughout the war as a researcher at a US Jewish Welfare organisation and as the publisher of Jewish literary works, including the diaries of Franz Kafka. After the war she took on the grim task of collecting and re-distributing to university archives ‘cultural property’ once belonging to entire families of Jewish intellectuals who had been wiped out, leaving no heirs to inherit. This property mainly consisted of collections of books which the Nazi Student Union organisations had not got round to burning. Family silver, gold, paintings and other valuables of exterminated Jewish families had for the most part been melted down and smuggled out of the country to Switzerland and elsewhere towards the end of the war, or along the same sort of ‘ratline’ escape routes used by Eichmann to reach Argentina.

Arendt’s 1951 book On the Origins of Totalitarianism was the culmination of her research into the nature of anti-semitism. It begins its analysis with the case of Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer of Jewish descent who in the 1880s had been falsely convicted of spying for Germany and subsequently found to have been framed by as a scapegoat for French military failure. But even after he was found have been framed, many in France continued to believe that he was a spy simply because he was Jewish. A paranoid style had been introduced into politics whereby concrete evidence of innocence is said to have been forged and therefore seen as even more conclusive evidence of deviousness and guilt. The ‘affair’ divided and defined French politics for decades, right up until modern times.

The significance for Arendt was that the more the evidence piled up in favour of Dreyfus, the more certain the anti-Dreyfus that this evidence had been faked and the more certain they were of his guilt. The success of the anti-Dreyfus movement depended on something that Arendt believed to new and unique to the modern world, especially the world of newspapers and mass communication – the valuation of feeling, emotion and conviction over evidence, facts and dispassionate analysis. What made both the Nazi German and Soviet regimes different to older forms of tyranny was their use of ‘thoughtlessness’ not in the sense of stupidity or inconsideration but as the systematic attempt to abolish the ‘inner dialogue’ of thought, and replace it with faith and irrational, unthinking submission to authority.

This had been made possible, Arendt argued, because modernity had transformed organic, small-scale communities where dialogue, discussion and co-operation took place, into teaming cities full of atomised individuals with no need or opportunity to develop their thinking in discussion with others. Classes and communities had been transformed into ‘the masses’ who were ‘thrown back onto themselves’. In these circumstances the inner dialogue we all experience – ‘is this right, is that true, what should I do’ – becomes painful for lack outlet in the form of serious or important conversation. Totalitarian political movements became popular because they removed the need to think, indeed made the whole process of agonising over judgement and difficult decisions, dangerous or even illegal. The official state slogan of the Italian fascist state was Believe! Obey! Act! The totalitarian regimes had simplified their dogmas to the extent that any difficulty or unease could be attributed to a despised scapegoat. Such scapegoats existed in the atomised public imagination as inexplicably influential ‘pariahs’, meaning people who had committed unforgivable and scandalous crimes or ‘parvenues’, meaning newcomers who benefited from society without contributing to it. All totalitarian regimes effortlessly mobilised ‘the masses’ against such people, or people who could be portrayed as such. The emphasis on the Jews – and to some extent the Gypsies – was that they could be portrayed as being both pariah and parvenue.

Elimination of the Jews was not, Arendt argued, the aim of German totalitarianism, rather it was the case that anti-semitism was a convenient tool. Still less important in either the German or Soviet was the doctrine that the ‘ends justifies the means’ - the preposterous supposed aim and justification of creating a utopian world society after all the killing and removal of undesirables had been completed. It was doubtful that any intelligent member of the SS or the KGB believed that such a conflict-free worldly paradise was a genuine possibility. The real aim had been in the institution of an unthinking, anesthetised regime of violence and terror with no aim clearer than its own immediate survival and spread: ‘moral fungus’.

On the Origins of Totalitarianism established Arendt’s reputation as an academic of the first rank. Others described her as a philosopher or political philosopher, but she was never comfortable with the title. Her break with Heidegger had not been complete, despite his Nazi activities. After the war Heidegger had been banned from teaching in German universities, but still found an audience in the form of public lecturers given to German business and conservative groups. His work had found a following amongst French intellectuals. Jean Paul Sartre, the populariser of the radical ‘counter-cultural’ existentialist movement was a dedicated supporter of Heidegger. Sartre’s own main work Being and Nothingness, was an attempted development of Heidegger’s 1927 book Being and Time as a thorough going rejection of the main thrust of European philosophical liberalism. Arendt met Heidegger regularly through the 1950s, and some who knew her, including the writer Adam Kirsch, even claimed that they had renewed their love affair.

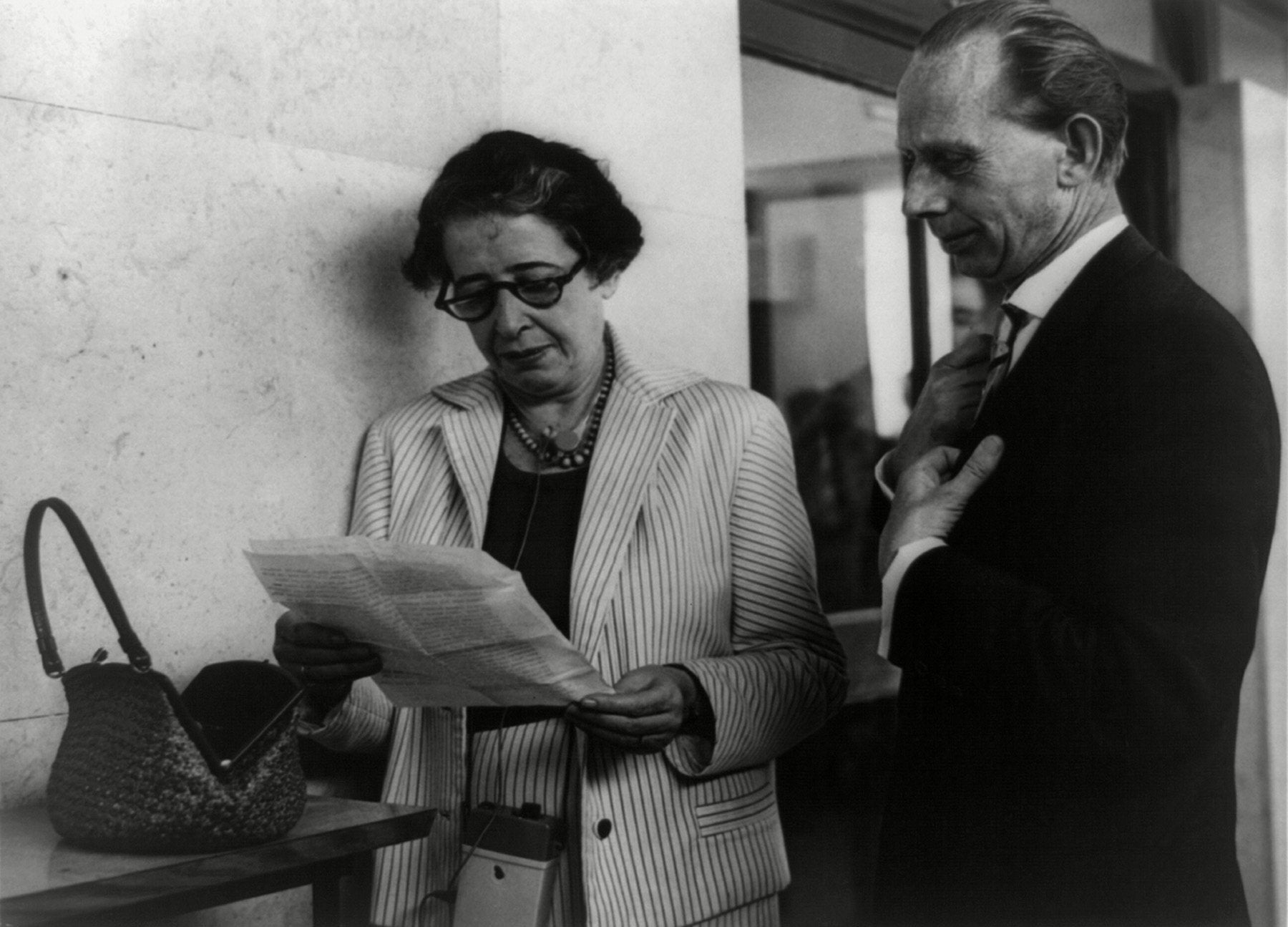

Arendt, like the French existentialists, took from Heidegger the idea that modern philosophy had taken a wrong turn in its subordination to physics, economic growth, technology and extreme liberalism; and especially his critique of modern ‘mass’ society and the prevalence of mass media. The academic discipline she argued in a number of lectures and books, was in such a mess that she preferred to call herself a ‘thinker’. Her critics in professional academia were happy to agree, and often described her, especially after the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem as merely a journalist – the ultimate insult. Nevertheless she was appointed in 1959 as a full professor of philosophy at Princeton University, becoming the first woman to hold a such a position at any comparable institution anywhere in the world. Two years later she added international fame to academic distinction with her coverage of the Eichmann trial and the coinage of ‘the banality of evil’ phrase.

For Arendt the one of the most shocking aspects of Eichmann’s trial was his attempt to defend himself by citing the work of Immanuel Kant, the 18th century author of The Critique of Pure Reason. Kant was the starting point and central figure in all subsequent development of the theory of justice just as, say Mozart, had been a central figure in the development of music. Arendt had conducted several studies of Kant and like anyone in any philosophy department knew his work inside out. Consideration of Kant was thus to become yet another thread linking Arendt and Eichmann.

The essence of Kant’s moral philosophy was that a person ought only to act in line with rules - ‘maxims’ as he called them – which could be legislated as general laws which any reasonable adult could be expected to obey. In simple terms Kant’s system represented not much more than the old principle of ‘do unto others as you wish them to do to you’ which, in Kantian terms, is usually called The Categorical Imperative. The point was that he claimed to have proven with logical precision over hundreds of pages of densely argued text that this principle was both valid and sufficient to allow people to live freely as human beings. Kant’s moral philosophy was one of the pillars of the modern world. He had liberated mankind from the middle-ages and the need for laws and rules to be imposed from a superior authority such as a God, prophet or any other authority figure. In Kant’s system only children and the mentally enfeebled were required to obey the authority of a father figure. The human race had come of age and was leaving its moral infancy behind. The Kantian ‘categorical imperative’ provided a logically undeniable case for democracy, personal freedom and civil liberties.

Eichmann quoted Kant extensively to say that in the early part of his career he had indeed worked in line with the categorical imperative. He had done nothing that he could not have imagined another person doing, and his plans to ‘assist’ and ‘encourage’ Jews to leave Germany would have been to their benefit had they been carried out. He would have expected Jewish authorities to have offered the same ‘help’ to him and his family, had the roles been reversed. Later, after Hitler had ordered the final solution, Eichmann said that moral responsibility had been taken out of his hands. He even drew comfort from the fact that Hitler had personally commanded the implementation of the final solution. Under Kant’s categorical imperative Eichmann said that he had a duty to obey orders that came from his superiors, since he would expect his own subordinates to follow his own orders. It would be wrong for him to blame his employees for crimes he had commissioned. In the same way it was wrong to blame him for crimes devised by Hitler. Eichmann showed no remorse or contrition. Not only was he innocent of any crime, it was also wrong to hold him morally accountable for carrying out the orders of his superiors, since refusing to follow those orders would have been in itself an immoral act.

In the final part of Eichmann in Jerusalem Arendt addresses her subject directly, in the form of an imaginary conversation. She ridicules Eichmann’s claim that Hitler’s enactment of the final solution meant that he no longer had any control over his actions, no longer ‘master of my own deeds’ as Eichmann had put it. Kant was clear that a man becomes the legislator of his own morality the moment he has any autonomy of action in the world. ‘Practical reason’ which Kant said was innate in all healthy personalities, would dictate that he should not carry out an order which he knew would be unjust - indeed endlessly and pointlessly cruel - if applied to himself or to his family. And Eichmann was indeed a healthy personality, in the simple sense of the term. He had been examined by three psychologists for the purposes of his trial, and all of them found his state of mind to be unremarkable. One of the psychiatrists had even declared Eichmann to have been more normal and emotionally stable than himself.

According to Arendt, Eichmann’s main crime had been ‘thoughtlessness’ – not in the sense of straightforward stupidity or lack of attention, but the in the much more profound sense of collapse of internal dialogue and therefore conscience she had described in On the Origins of Totalitarianism and developed in a subsequent essay published in 1958. Arendt dwells on the picture of offended mediocrity he presented. Here was a ‘random buffoon’ who was ‘not even sinister’ but the very definition of ‘an inoffensive nobody’. He was a ‘superficial conformist with no sense of personal responsibility’. His motivations, at least according to Arendt, were not the desire to inflict suffering, but to please his boss, to save money by booking transport trains to the camps efficiently, deliver reports on time and fit in with those around him. The way Arendt portrays him, Eichmann was the sort of person you might today find in any office (or at the moment on Zoom), mildly annoying in his adherence to petty rules, but always sure to do his fair share on the coffee rota and ready to dispatch you to a gas chamber without a second thought.

The mass murders in Rwanda, for example, were marked by a type of premeditation and exhilaration, to match the mindlessness and boredom of Arendt’s picture of the Holocaust, in almost equal and opposite measure

Arendt noted that Eichmann’s desire for acceptance by those around him was so great that in his Argentine exile he had boasted about committing atrocities for which he was not responsible and in fact would have been impossible for him to have carried out. He wanted to fit in with Nazi émigré and extreme right circles he relied upon for his humdrum suburban lifestyle in Argentina. Eichmann spoke about his time in Argentina as part of his testimony in Jerusalem: “I sensed I would have to live a leaderless and difficult individual life, I would receive no directives from anybody, no orders and commands would any longer be issued to me, no pertinent ordinances would be there to consult - in brief, a life never known before lay ahead of me”. Such sentiments were typical of an atomised individual within a totalitarian, Arendt said, system – finding it intolerable to be “thrown back on himself” and eager to find somebody – anybody – to tell him what he should do with his otherwise entirely empty life. Arendt notes that it was his boasting that brought him to the attention of Israeli intelligence, and therefore his trial and execution.

Eichmann’s pathetic attempts during his trial to use Kantian liberal moral philosophy in defence of the indefensible presented her in the starkest terms with an example – almost a laboratory specimen – of the atomised modern human robot, both the cause and the result of the new phenomena of totalitarianism. Eichmann and millions of others were capable of carrying out unspeakable horrors because totalitarian systems had removed their capacity to reflect and think, and replaced it with imperatives to obey and act without thought for consequences.

Arendt to re-examine and develop Kant’s thinking in a series of lectures and academic papers in the years that followed. She concluded that in the modern world Kant’s categorical imperative needed to reflect the greater opportunities for harm presented by modern technology. Now, in the nuclear age, and in the light of two world wars and the holocaust, a new moral test was needed: “Can I live with myself if I commit this act”. By now others in American academia were beginning to think along the same lines as Arendt. Directly inspired by the Eichmann trial Stanley Milgram at the psychology department at Yale university devised an experiment which appeared to show that a majority of perfectly stable volunteers were prepared to inflict what appeared to be extreme and increasing torture by way of electric shocks on a victim, simply because they were told to do so by an authority figure in a doctor’s white coat. The experiment, which has been criticise for its methods and some of its conclusions more recently, seemed to provide yet further empirical, laboratory-standard evidence that evil was indeed more banal, pervasive and fungus-like than people liked to think.

Arendt’s writings and ideas have by and large stood the test of time and the juxtaposition of the holocaust, American intellectual life (vastly enriched in all fields by the arrival of émigré intellectuals, from Germany), the precarious position of the state of Israel, the persistence of anti-semitism and the seemingly endless and irreconcilable conflict in the middle east means that her themes have remain sadly current. Arendt was accused of being insufficiently loyal to the cause of Israel by some, and even portrayed as a traitor for the sarcasm she poured on the Israeli’s claims to have been interested in giving Eichmann a fair trial, in terms of presumption of innocence. She opined that the Israeli authorities would never have put Eichmann on trial if they thought there was the slightest chance of him being found innocent – the result would have been a political disaster beyond measure. In any case the stated purpose of the trial, as set out in terms by the prosecution, was to put anti-semitism itself on trial, and to work through systematically the evidence of the crimes committed against the Jewish people in a way which would never be forgotten, and therefore never repeated.

Others never forgave her for suggesting that Eichmann had been subjected to a political ‘show trial’ which was broadcast to the world as a type of propaganda to justify the foundation of the state of Israel; still others said that she exhibited an indifference to the fate of the Jews of Poland and eastern Europe, especially the orthodox or highly devout, who educated and secular Germans such as herself ended to view with distain. More recent scholarship has shown that Eichmann may have been far more motivated and responsible anti-semite than Arendt had realised. Certainly Eichmann had been a cog in the machine, but one perfectly capable of the using the imagination and initiative that Arendt claimed totalitarianism obliterates in its functionaries.

The destruction of the USSR came after her death in 1975 and seemed to undermine her thesis that totalitarianism was an invincible force, or – despicable as it was – that the KGB and the ramshackle East European satellite states were the functional equivalents of the Third Reich, or even Imperial Japan. Subsequent genocides or attempted genocides, such as those in the former Yugoslavia or Rwanda, seem to refute her model, at least to some extent. In both cases the violence was not the result of a nihilistic elite manipulating mindless and defenceless atomised citizens, the lonely victims of the atomised modernity which both Arendt and Heidegger so despised. The violence was inspired by old fashioned ‘bottom up’ racial hatred and tribal vendetta. The mass murders in Rwanda, for example, were marked by a type of premeditation and exhilaration, to match the mindlessness and boredom of Arendt’s picture of the holocaust in almost equal and opposite measure. Many of the killers in Rwanda said they found a type of sadistic pleasure in routine murder, for which they used the same tool – the manchette – but which they found less boring than farming. It seems to show that the weakest part of Arendt’s work is her underestimation of dark psychological drives, especially those connected with male sexuality. Like all over-arching theories in politics and philosophy Arendt’s offering have flaws which may or may not be corrected by further research and refinement. It may take a little longer yet to come up with a satisfactory and comprehensive theory of good and evil to match the dangers of the modern world.

Nevertheless, Hannah Arendt’s name will forever be associated with the disenchantment and de-romanticising of evil, as she put it – the epithetic about the “banality of evil”. Three years after the publication of Eichmann in Jerusalem, during a radio interview, Arendt went further with an even more pungent and unsettling epithet or slogan, which is now emblazoned across the decorated frieze of the former fascist headquarters and torture centre in Bolzano, Italy:

Nobody has the right to obey orders.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments