George Harrison was one of the great cultural pioneers of modern times

On the anniversary of the Beatle’s death, Sean Smith celebrates the memory of a man who made a difference not just to music but to the world

Is it really 21 years since George Harrison became the second Beatle to leave us? He died in a mansion in the Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles, after a long struggle with lung cancer on 29 November 2001.

Harrison was so much more than the understated, unfussy lead guitarist with the most famous pop group of all time. He deserves to be recognised as one of the great cultural pioneers of modern times – as a musician, a composer, a film producer, an innovator and as a man who used his fame to advocate for the causes that matter in the modern world.

Everyone has a favourite Beatles song, but those iconic riffs that introduced us to the sound of the Sixties and the hysteria of Beatlemania were based around the maestro of the melody.

And it’s not easy. Air guitar aficionados will know that it is far simpler to be a bedroom Jimi Hendrix than to imitate Harrison playing a precise two or three minutes of finger-picking melody.

Guitar virtuoso Keith Krykant, who taught guitar to a young Ed Sheeran, explains, “The guitar is a complex instrument. Jazz and classical guitarists will study for many years to achieve the skills to play melodies, bass lines and chords all at the same time. But most ‘popular’ music guitarists seem reluctant to take the time to reach these levels because of the complexities of the fingerboard. Harrison was an exception. I have always respected him for his choice of notes and his positioning of them across all six strings and along the frets.”

It was Harrison who actually taught John Lennon to play the guitar properly back in their early Liverpool days. None of the Fab Four had musical backgrounds: Harrison was the son of a merchant seaman, Harry, who later became a bus driver. He had brought back a wind-up gramophone from a stop-over in New York on one voyage and that was one of the few luxuries they had at the tiny terraced house in Albert Grove where Harrison was born in the front upstairs bedroom in 1943 when the residents of the Wavertree district lived in constant fear of the German bombing raids.

Harrison was the youngest of four children, all of whom hated getting up in the morning because it meant a shivering visit to the outside toilet. Their upbringing was distinctly humble with just one coal fire straining to heat the house.

While his father showed little interest in religious matters, his mother Louise was from a traditional Irish Catholic family. She liked nothing better than belting out a song at the top of her voice that could be heard in the Anfield football stadium a couple of miles away.

Harrison, however, formed an obsessive interest in the guitar at a young age. He would sit in the back of class at his secondary school and draw guitar shapes in the back of his exercise book. With typical understatement, he once said: “I was totally into guitars.” By this time he owned his first, a flat-topped acoustic guitar that his dad had picked up for a couple of quid.

He learnt some American standards – songs like “Dinah” which Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby recorded. More importantly, he had some jazz guitar lessons from a teacher who loved Django Reinhardt, one of the greatest guitarists of all time. Many of the familiar “diminished” Harrison chords came from this formative influence.

Like most teenagers, however, the charts were crucial. He would soon be a big fan of Lonnie Donegan whose skiffle sound was breaking through in 1956. He even started his own skiffle group at school along with elder brother Peter.

The first Beatles to become friends were Harrison and Paul McCartney who also attended the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys. They realised they shared a love of guitars and the music of rockabilly legend Carl Perkins while chatting on the bus to school one day. Perkins had memorably recorded “Blue Suede Shoes” in 1956. Harrison even took to using the professional name Carl Harrison for a while.

Despite his early reservations, Lennon was smart enough to recognise his potential – especially when the younger boy showed him how to actually play the guitar

A year later, in July 1957, McCartney met John Lennon and his band, The Quarrymen, at a fete in the suburb of Woolton. McCartney would join the band and suggested that they should audition his school friend Harrison. Lennon wasn’t that keen when he realised Harrison was just coming up 15 while he was nearly 18 which is light years older when you’re a teenager.

The audition wasn’t anything official – just three lads on the top deck of a double-decker bus with Harrison picking his way through the annoyingly twangy fifties instrumental hit “Raunchy” by Bill Justis. Practically everyone at the Liverpool Institute had heard Harrison play his schoolboy signature tune.

Despite his early reservations, Lennon was smart enough to recognise his potential – especially when the younger boy showed him how to actually play the guitar. Harrison revealed his tuition during his testimony in a court case in 1998 against the owner of a bootleg Beatles recording.

“When I joined, he didn’t really know how to play the guitar,” said Harrison. “He had a little guitar with three strings on it that looked like a banjo. I put the six strings on and showed him all the chords – it was actually me who got him playing the guitar.”

At first, Harrison was a stand-in if one of The Quarrymen was ill but after he left school at 16 he became an essential member of the group that would become The Beatles.

He didn’t write any of the early songs as Lennon and McCartney forged what would become arguably the greatest songwriting partnership in pop history, even if they didn’t in fact write many of the famous Beatles masterpieces together.

Harrison, by contrast, was very much a lone writer. During an early summer season, he fell sick and was confined to a hotel room in Bournemouth and decided to write a song to see if he could do it. The result was the unmemorable “Don’t Bother Me” which Harrison candidly judged as “not a very good song”, although it did inspire him to keep writing.

“Don’t Bother Me” was given a space on the Beatles’ second album With the Beatles, although it’s fair to say that Harrison’s early efforts were more tolerated than enthusiastically embraced.

The songwriting ability of the boys was not necessarily of paramount importance to the millions of screaming female fans. Harrison was arguably the most popular during the heady days of Beatlemania simply because he was the youngest, although McCartney with an appealing baby face ran him close. The youngest member of a group always has a head start in the popularity stakes – just ask Robbie Williams (Take That), Justin Timberlake (Nsync) or Harry Styles (One Direction).

And just like those future superstars, Harrison gradually matured into a hugely accomplished songwriter and influential figure, eventually contributing 21 songs to the Beatles’ songbook including three of their all-time most popular and acclaimed works – “Here Comes the Sun”, “Something” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”.

His next songs for the group were not until Help! was released two years later in 1965 to which he contributed “I Need You” and “You Like Me Too Much”. However, these were overshadowed on the album by “Yesterday” and “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away”. Much more significant, perhaps, was a happy accident that occurred on the set of the film of Help! There’s a scene set in an Indian restaurant and one of the musicians is playing a sitar. For the first time, Harrison noticed the intricacies and possibilities of the instrument so closely associated with Indian classical music.

Harrison’s initial interest was further piqued by hanging out with David Crosby – then one of the key members of the group The Byrds – while The Beatles were on an American tour that summer. Crosby had an LP of the sitar maestro Ravi Shankar in his suitcase and gave it to Harrison to enjoy which he did enthusiastically.

His lifelong love of Indian music had been initiated and on his return to London, Harrison bought a sitar from a shop in Oxford Street and set about learning the instrument himself. The fruits of his first labours were heard on the next Beatles album, Rubber Soul, which includes a sitar solo on the John Lennon-written classic track, “Norwegian Wood”.

By the release of Revolver, the influence of Indian classical music on Harrison and the rest of the group was much more evident, never more so than on his composition “Love You To”. The writer Dipankar De Sarkar observed: “The song is without doubt a path-breaker in its uncompromising adherence to a form of music that was alien to Western pop.”

These days Revolver is almost universally acknowledged as The Beatles’ finest hour. As recently as June, The Independent ranked it number one amongst The Beatles’ 12 albums noting the influence of drugs, psychedelia and Eastern religion. De Sarkar noted that “An Indian Summer lit up the Swinging Sixties.”

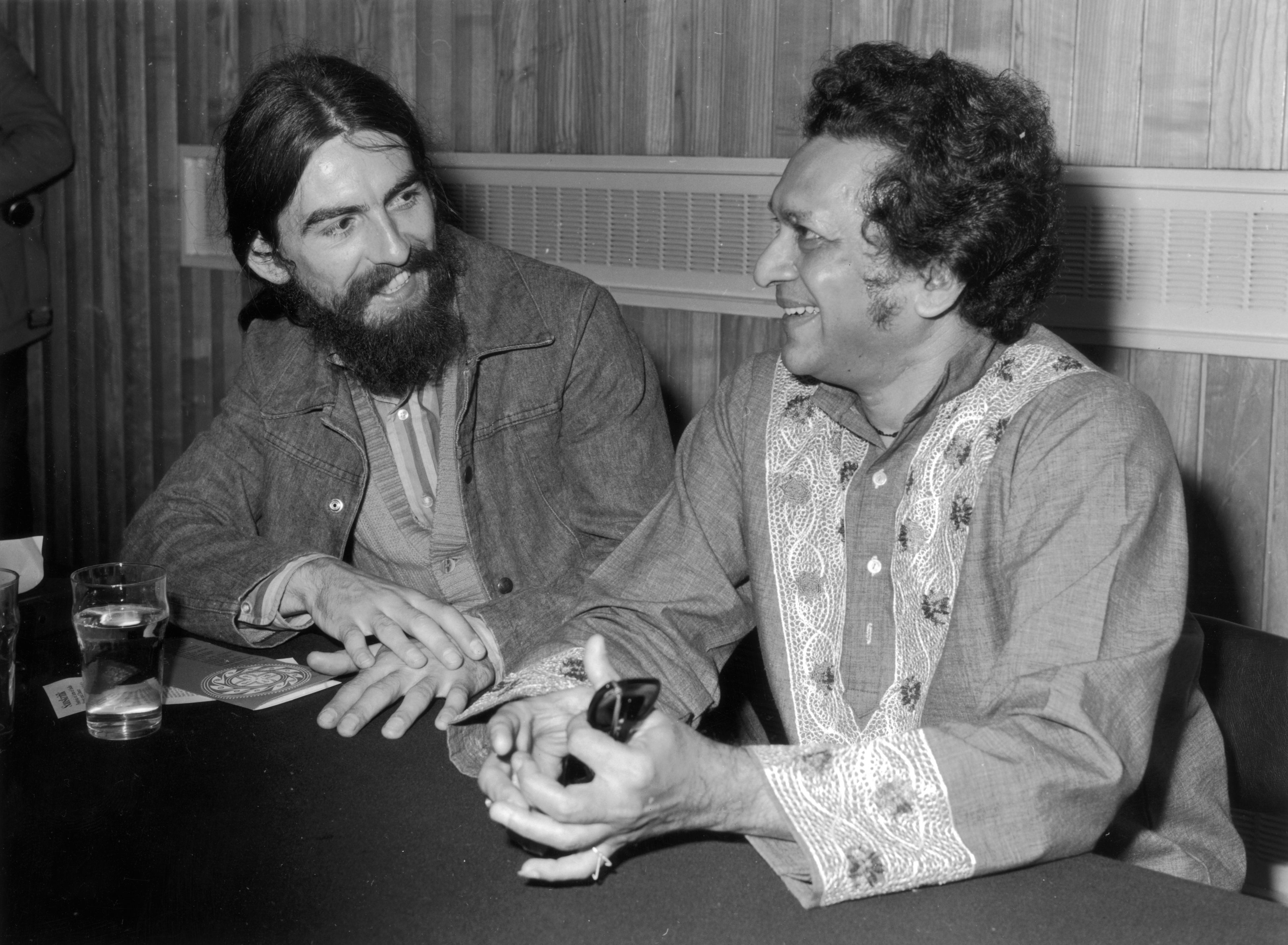

A couple of months after recording “Love You To”, Harrison finally met Ravi Shankar when the revered musician was playing a concert in Bath alongside Yehudi Menuhin. Harrison persuaded Shankar to tutor him in the art of Indian music – an influence that would stay with him throughout his musical journey.

He wasn’t that thrilled that Frank Sinatra performed ‘Something’ many times, especially when the legendary singer introduced it as a Lennon and McCartney number

These were momentous times in Harrison’s life. He married the Sixties model Patti Boyd in February 1966 who he had met two years earlier on the set of the first Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night in which she had a blink-and-you-miss-it role as a schoolgirl. She was very much part of Harrison’s adoption of Indian culture spending six weeks with him later that year in India as guests of Shankar.

Back in London, Boyd spotted an advertisement for transcendental meditation classes and persuaded Harrison to join her. Along with the other Beatles, they attended a lecture by the Maharishi and were deeply impressed. “We were spellbound”, Boyd wrote in her first memoir, Wonderful Tonight.

The following year, the Maharishi invited The Beatles among many other celebrities to his ashram in India. Harrison was in his element in brightly coloured robes and cotton pyjama trousers. He took the meditation very seriously telling the photographer and filmmaker Paul Saltzman: “The meditation buzz is incredible. I get higher than I ever did with drugs. It’s simple … and it’s my way of connecting with God.”

The Beatles were soon on their path to breaking up for good but Harrison was on his most creative journey. The uber-romantic “Something” which featured on Abbey Road would become the most covered of all his songs. He wasn’t that thrilled that Frank Sinatra performed it many times, especially when the legendary singer introduced it as a Lennon and McCartney number. Harrison had envisaged it being recorded by Ray Charles. Sinatra did, however, call it the greatest love song of the last 50 years.

Harrison’s creative surge did not end with The Beatles. In fact, he gained momentum with the first solo number one of any of the group: “My Sweet Lord” was the biggest-selling single of 1971 and the lead track from the ground-breaking album All Things Must Pass, the first triple album by a solo artist.

The live version of the song would prove a highlight in August of that year when The Concert for Bangladesh took place at Madison Square Garden in New York. Harrison had organised it in tandem with Shankar and it was the first rock concert to highlight a desperate world situation as Live Aid would 14 years later. Harrison’s concert proved to be the model for every superstar benefit for years to come – a true forerunner of rock altruism.

Up until then, little had been known around the world about the desperate plight of 10 million East Pakistani refugees that had fled across the border into India. They desperately needed food and basic medical equipment to survive.

As well as Harrison and Shankar, the all-star lineup also featured Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton. The live album won the Grammy Award for album of the year in 1973 and had continued to raise money for the George Harrison Fund for Unicef ever since. The record concludes with Harrison performing “Something” and the song he had specially written entitled “Bangladesh”.

Harrison was also the producer of the accompanying movie, his first foray into the world of films that would prove hugely significant for the British film industry. Most famously, he set up Handmade Films to finance Monty Python’s Life of Brian, one of the most acclaimed comedies of all time. He reportedly used £3m of his own money to finance the movie, observing drily that he did so because he was to see the movie. The Pythons described the gesture as “the most expensive movie ticket in history”.

Harrison was executive producer on some of the most iconic British films of the Eighties including Mona Lisa, A Private Function and Withnail and I. By the time his involvement with Handmade Films had ended, Harrison had started The Travelling Wilburys with Jeff Lynne and featuring Dylan, Roy Orbison and Tom Petty. For many, it was the ultimate supergroup because of the diverse musical range of the members.

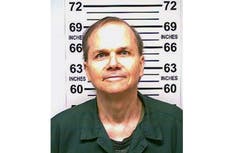

He was very nearly the second Beatle to be murdered following the assassination of Lennon in 1980. An intruder broke into his home near Henley-on-Thames in 1999 and stabbed him multiple times. His second wife Olivia saved him by battering the assailant with a poker. Harrison was treated in hospital for many injuries including a punctured lung.

Typically Harrison observed afterwards – or so legend has it – “He wasn’t a burglar and he certainly wasn’t auditioning for the Travelling Wilburys.”

When he died two years later Harrison had not received the knighthood he so richly deserved. Shamefully he was offered an OBE shortly before his death and he refused. He may or may not have been peeved by the fact that McCartney was already Sir Paul.

His final words are a better legacy in any case: “Everything else can wait, but the search for God cannot wait… and love one another.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks