The genocide and inhumane tactics that characterised the Biafran war

The Nigerian civil war, which ended 50 years ago today, came to define post-colonial Africa. But it was the images of Biafra’s starving people that came to symbolise the horror of modern warfare, writes Kevin Childs

A photograph taken in April 1968 by the British photojournalist Don McCullin shows a young Biafran soldier carrying a wounded comrade from an encounter with the federal Nigeran army during the Biafran war. He looks at the camera. Hardly acknowledging McCullin’s presence, he is intent on what he has to do; there is no particular emotion on his face – perhaps recognition, though even that is passing.

But this is a child, maybe 13 or 14 years old, his wounded comrade even younger. Possibly one of the earliest images of a phenomenon that has come to haunt African conflicts and the continent itself, the photograph indicates that this is a war into which the entire population was drawn – men, women and children – a war, some have said, for existence.

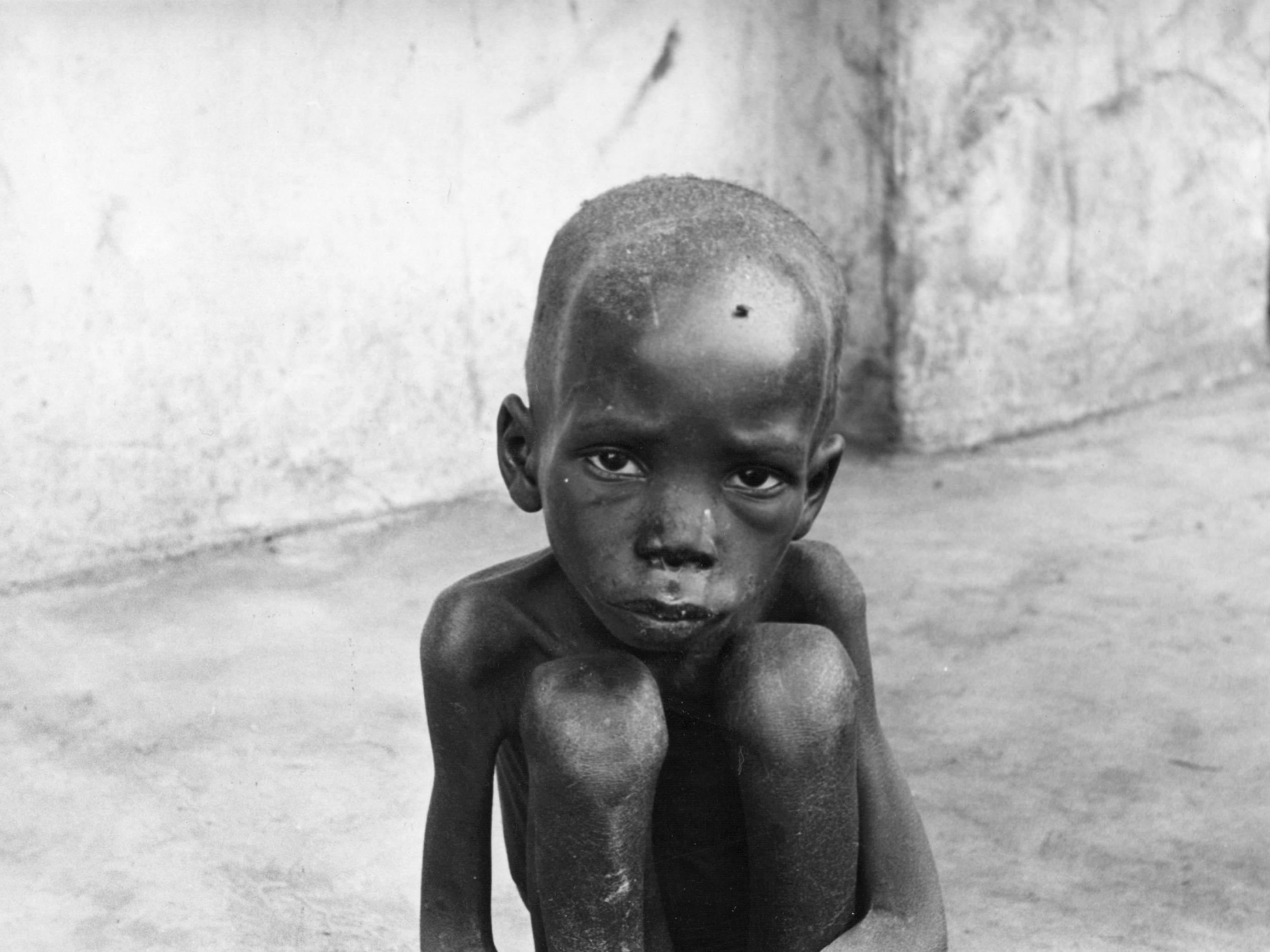

The Biafran war, which formally ended 50 years ago today, came to define post-colonial Africa for many in the west. Images of determined young Biafran soldiers eager to fight the might of the federal Nigerian army with woefully inadequate supplies of arms mingle with pictures of starving children – stick-like limbs, protruding bellies, sad, soulful eyes – and emaciated mothers clinging to dead or dying babies. They were the victims of a concerted effort to starve the population of Biafra into submission or extinction. It was a tragedy on so many levels.

In September 1967, not long after hostilities broke out, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), recently set up as a dispute mechanism for African states, began the long process of washing its hands of the war, characterised by its head as “a domestic affair” and therefore beyond their remit. Over the next two years, there were conferences held in various capitals which could only ever have a consultative function – the federal government in Lagos refused to allow any mediatory role.

In debate after debate in the Houses of Parliament, Britain’s government defended its stance on the war, echoing the OAU and much of the international community when they stated this was an internal matter for Nigeria.

In 1969, several months before the end of the war, journalist Suzanne Cronje and novelist Auberon Waugh published a book laying this supposed neutrality bare and pointing the finger firmly at the British government for the unfolding tragedy in west Africa. Biafra: Britain’s Shame may have had Harold Wilson’s government in its sights, but the authors were equally scathing about the Conservative opposition under Edward Heath, which basically toed the government line: the integrity of the state of Nigeria as it was constituted at independence must be maintained at all and any costs.

Since independence in 1960, Nigeria has always been something of an anomaly. The amalgamation of different and disparate colonies in 1914 was only ever purely for British administrative purposes. The peoples of the north, south and southeast of modern-day Nigeria have retained distinct cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious identities. Before independence, stark differences between these regions were glossed over by the British colonialists. At the time of the amalgamation, the then governor, Lord Lugard, a miserable racist if ever there was one, wrote to the government in London explaining the “need” for the creation of a single colony: “What we often call the Northern Protectorate of Nigeria today can be better described as the poor husband whilst its southern counterpart can be fairly described as the rich wife or the woman of substance and means. A forced union of marriage between the two will undoubtedly result in peace, prosperity and marital bliss for both husband and wife for many years to come. It is my prayer that that union will last forever.”

It was a policy of monumental errors, a recipe for conflict based on a racist notion that somehow all Africans are the same and need to be moulded to the will of their colonial masters. The administration of the north was left to a group of hardline Islamic emirs to run as personal fiefdoms controlled by strict Sharia law. The predominantly Christianised south and southeast, mainly Yoruba and Igbo respectively – although there have always been smaller ethnic minorities in all regions – was, by and large, more democratic, educated in a westernised tradition, industrialised and commercially savvy.

Conflicts between these identities have flared up periodically since the 1930s, when large numbers of educated Igbo people from what would become Biafra were moved to the Islamic north to fill jobs which the indigenous Hausa and Fulani peoples – nomadic herders and traders – were deemed too ill-educated to do for themselves. Here was a formula for ethnic hatred stirred by religious intolerance. Pogroms against Igbos in the north in 1945 and 1953 were a foretaste of what was to come.

Before independence and during the first six years of the existence of the fledgling state of Nigeria, both the north and the southwestern provinces had threatened secession from the federal administration run from Lagos, each ethnic group fearing domination by others. But the old colonial power, Britain, and allies in the US and Canada, had always diluted the bitterness while promoting the idea that the supposedly more populous north ought to have the greater say in Nigeria’s affairs.

It had been the Igbos and Yoruba of the south and east, after all, who had been at the forefront of demands for independence. And they wanted complete independence, not a state that was still effectively in hock to the British, who controlled its oil and mineral wealth through favourable deals offered to Shell BP. By handing power to politicians from the north, the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan hoped to manipulate Britain’s old colony through reliance on a loyal northern elite, led by Ahmadu Bello and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, and exclude the more critical politicians of the south. Only its president, Nnamdi Azikiwe, who carried out an almost entirely ceremonial role, was Igbo. Otherwise, Igbos were conspicuously absent from the new government.

The year of 1966 was one of coup and counter-coup. Igbo officers took control in January – Balewa, Bello and a number of high-ranking northerners in the government were summarily executed – attempting to impose a government of national unity. But in July a further coup, led this time by officers from the north, coincided with a series of attacks on Igbos living in the north and central parts of Nigeria. This led to a panicked shift of populations back to the southeast. Between July and October 1966, it’s estimated that 30,000 Igbos were killed, mainly with guns and machetes, with well over a million fleeing back to their heartlands, their properties looted by northern soldiers, bringing with them terrifying stories of rape and mutilation. The people of the southeast, particularly Igbos, looked on with dread as a new military government dominated by northern officers took power. It was led by General Yakubu Gowon, a northerner who was neither Hausa nor Fulani and Christian rather than Moslem.

Attempts at mediation between an increasingly agitated and isolated southeast, now led by its military governor Odumegwu Ojukwu, and the rest of the federal military government at first appeared successful. An accord was signed in Aburi, Ghana, in early 1967 between all regions whereby Nigeria would remain as a loose federation of states, each of which was responsible for its own revenues. Gowon would stay as president of the federation.

As soon as he returned to Lagos, however, Gowon seems to have reneged on the deal, and it’s here that Waugh and Cronje see the influence of the British government, since 1964 a Labour administration led by Harold Wilson, with the lacklustre Michael Stewart as foreign secretary. They cite evidence that the British high commissioner in Lagos, Sir Francis Cumming-Bruce, dissuaded Gowon from implementing the Aburi accord amid fears that it would lead to the eventual breakup of the federation. Instead, Gowon proposed a further mashup of the states into 12 regions, dividing the southeast in three and leaving what would be a predominantly Igbo East Central State landlocked and cut off from the sea.

Port Harcourt, a major Igbo oil city on the coast, would be joined to a Rivers State run by ethnic minorities rather than the Igbo majority. The plan was to lever the eastern minorities away from supporting any potential move by Ojukwu and his Igbo-dominated South Eastern Assembly to declare secession.

But that is exactly what Ojukwu and the assembly did on 30 May 1967, announcing an Independent Republic of Biafra, named after the Bight of Biafra along its southern coast.

It was a policy of monumental errors, a recipe for conflict based on a racist notion that somehow all Africans are the same and need to be moulded to the will of their colonial masters

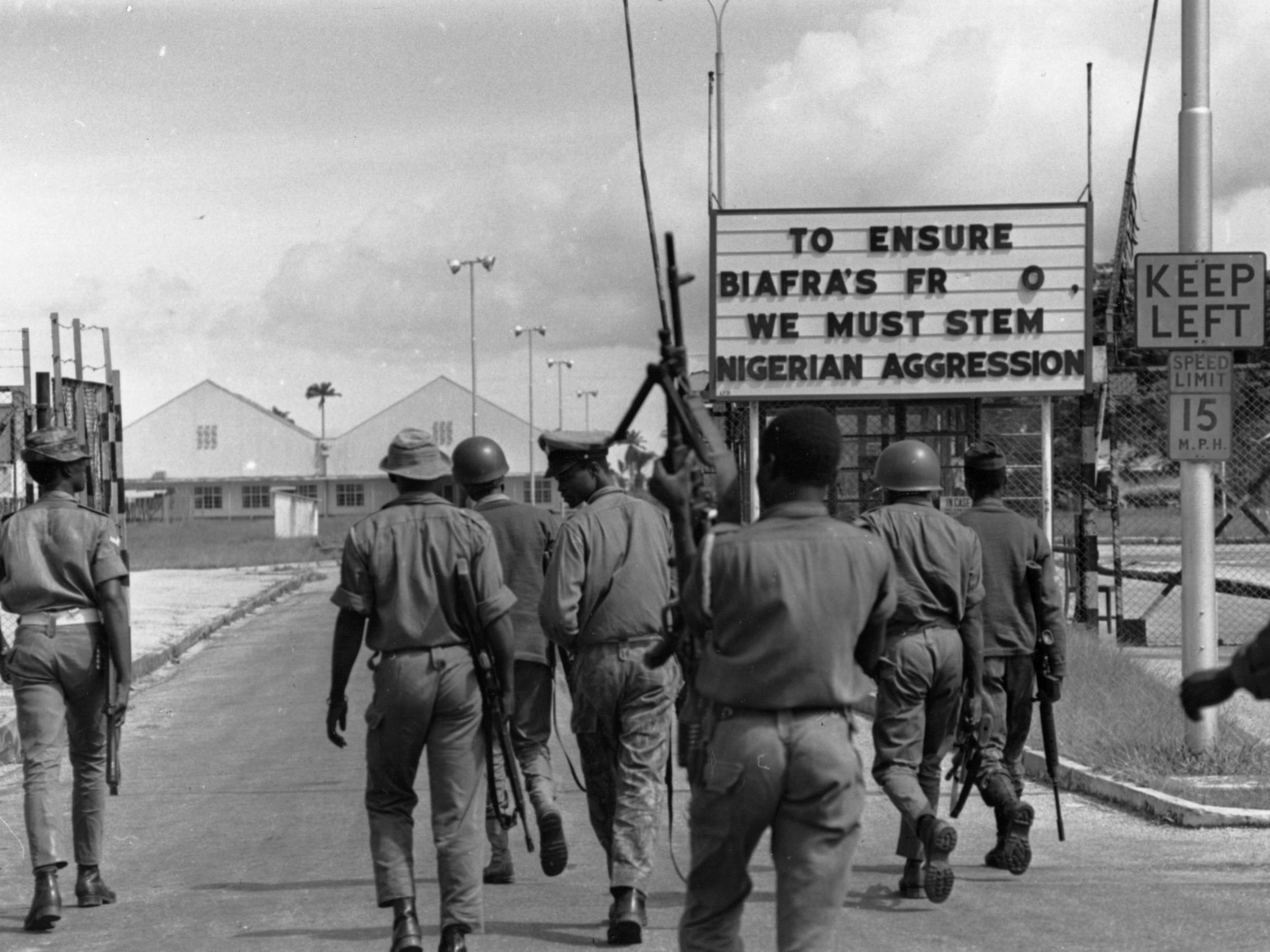

What followed was an uneasy shifting of positions. Ojukwu intended to hold a plebiscite of all the people in the new state, but the Nigerian government refused to acknowledge it and implemented a blockade. Biafra’s assets abroad were frozen after Ojukwu diverted revenues normally earmarked for Lagos to pay the government workers’ salaries in Biafra, in arrears for several months by this point. Then on 6 July, Gowon ordered a “police action” to bring Biafra back into the federation, essentially a full-scale invasion by the federal Nigerian army. As Radio Lagos announced the following day: “The commander in chief of the armed forces of Nigeria has issued orders to the Nigerian army to penetrate the East Central State and capture Ojukwu and his rebel gang.” Lagos had declared war on Biafra.

With the exception of four African states that recognised the new republic, it seems the rest of the world thought little of Biafra’s chances in a war with the federation. But for nearly two and a half years, Biafra held out in the face of impossible odds and a ruthlessly brutal opposition. The Nigerian army, dominated by men from the north, had little difficulty in finding the latest in weaponry.

The Soviet Union provided MiG fighter planes and heavy bombers, and the old colonial masters, not to be outdone by the Soviets, and clearly worried by a possible accord between oil-rich west Africa and the Russians, also flooded Nigeria with small arms and expertise in a bizarre twist in Cold War one-upmanship and localised arms racing. According to Waugh and Cronje, Harold Wilson’s Labour government claimed that stability and, curiously, neutrality, were the reasons that they provided the arms with which the Nigerian army would kill tens of thousands of Biafrans, while getting the Tory opposition onside with dark warnings of the Soviets’ African ambitions.

At first, the war ranged to and fro. The Biafrans made some territorial gains in the mid-western state, in August 1967 advancing as far as Benin City, but gradually the federal army’s fire-power superiority and use of jets and bombers to attack civilian areas, including schools and hospitals, turned the conflict into a war of attrition. The Biafrans were forced back across the River Niger from Asaba in early October. It was here that the first atrocity of the war was committed. The town was shelled over 24 hours and when federal troops entered, they began rounding up men thought to be Biafran sympathisers and shooting them in the streets. To stop the violence, the town’s leaders offered to pay the troops, but the men chosen to deliver the money were also shot. Finally, in an attempt to placate the federal soldiers, a parade of some 4,000 people assembled to pledge loyalty to Nigeria, only for the federal commander to hive off the men and have them machine-gunned, killing potentially over a thousand in a single day.

This was the “total war” that Gowon had promised after the Biafrans’ incursion across the Niger.

In January 1968 in London, the government denied helping either side in a debate in the House of Lords. Lord Shepherd, for the government, finally made a statement setting out its position: “While we deplore the tragic and sad civil war in Nigeria, we have been supplying Nigeria with pretty well all its military equipment, and in the present circumstances we think that we should continue to supply reasonable quantities of arms to the legal government of Nigeria. I would make it clear that none of these weapons are what can be described as mass destructive weapons, such as bombs and aircraft of that class.”

Between July and October 1966, it’s estimated that 30,000 Igbos were killed, mainly with guns and machetes, with well over a million fleeing back to their heartlands, their properties looted by Northern soldiers, bringing with them terrifying stories of rape and mutilation

Over the next few weeks, politicians in both houses would press the government on this issue. In May 1968, the prime minister Harold Wilson stated: “We have allowed the continuance of supply of arms by private manufacturers in this country exactly on the basis that it has been in the past, but there has been no special provision for the needs of the war. As I have said, we have refused to supply arms of a kind, such as bombs and other things which we were asked for, which were required, or considered to be required, for this war.”

Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe reminded Wilson that the majority of killing in Biafra was done using small arms and automatic weapons, not bombs. The anomaly in the British government’s position didn’t go unnoticed in other parts of Africa. Waugh quotes Ivory Coast president Felix Houphouet-Boigny, who was shocked by the callousness of the British approach: “That the Russians, faithful to their policies, should supply arms to the Nigerian government we can understand. That the British government, leader of the Commonwealth, whose duty it should have been to play the role of mediator, should furnish the most lethal weapons for the massacre of Biafrans, who are themselves citizens of the Commonwealth, surpasses comprehension.”

During the first half of 1968, as reports of atrocities and the extent of famine caused by the federal military government’s blockade of Biafra began to be known through news reports and photo reportage, a number of western countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium and France, banned the export of weapons to Nigeria. Even the briefly independent Czechoslovakia stopped supplying the heavy bombers their Soviet masters had insisted on. French president Charles de Gaulle maintained a tacit approval of the Biafran state and allowed French arms companies to supply the desperate Biafran army with weapons via France’s own ex-colonies in west Africa. In July 1968, he declared the war a matter of self-determination, saying: “The blood and the suffering borne for more than a year by the population of Biafra show their will to assert themselves as a people.”

Blockaded on land and by sea, the population of a shrinking Biafran state, swollen by influxes of refugees from all areas, slowly began to starve to death. Again, the British House of Commons debated this issue in June 1968 after ceasefire talks in Kampala had failed. The foreign secretary Michael Stewart had been blaming Ojukwu and the Biafrans for the breakdown of the initiative. Having none of this, backbench Labour MP Reginald Paget asked Stewart pointedly: “In view of the overwhelming evidence that the policy of the Nigerian army is to slaughter men, women and children, can one say that the Biafrans are responsible for breaking off the talks when the condition of the talks was that authority should be handed over to that Nigerian army?”

Stewart’s reply would come to haunt him: “I cannot accept the assumption of fact which he makes, and, in consequence, I cannot agree with his conclusion.”

Whether it had always been the intention of the federal military government in Nigeria to destroy Biafra and slaughter its population – Gowon’s declaration of “total war” is not absolute proof – someone was pulling the wool over parliamentary eyes in mid-1968. In another debate in August, the under-secretary of state for foreign and Commonwealth affairs, William Whitlock, effectively filibustered a vote on the supply of arms to Nigeria by refusing to end his speech. Tempers were high. General Gowon had announced a “final push” against the reduced Biafran state.

The journalist Colin Legum had recently published an article in The Observer implying that the intentions of the Nigerian federal government towards the Biafrans were essentially genocidal, the first time this word had been used in print. In reply to concerns of MPs that there was now a grave danger of the destruction of the Igbo people, Lord Hunt for the government made what has to be one of the most chilling comments on war imaginable: “Brutal and inhuman though it is, the very essence of siege tactics is to reduce the defenders to physical conditions which they can no longer endure… If [General Gowon] were to remove all the obstacles and drop all safeguards in the way of relief aid, he would not only be delaying the attainment of his objective – he has been delaying that for months – but would risk losing it altogether.”

In the end, no final push materialised at this stage, Gowon’s government preferred to let famine do its work. But bombing raids and a slow-burn invasion continued for another year and a half. Confirming the intentions of the federal military government in Lagos, in an interview with The Economist in August 1968 one military commander, described by Lord Hunt admiringly as “daring”, “colourful” and “outrageous”, Colonel Benjamin Adekunle stated: “If the children must die first, then that is too bad, just too bad… All is fair in war, and starvation is one of the weapons of war.”

What changed, and what prompted Waugh and Cronje to write their book in 1969, was a concerted effort on the part of friends of Biafra in the west to publicise the plight of the people who were being starved into submission. McCullin and the French photographer Gilles Caron had circulated images to the world’s press that came to define the horror of modern warfare and the victimisation of women and children particularly. President Johnson’s administration in the US, which had maintained supposed neutrality, was forced to send fact-finding missions and offer US planes to church organisations who were arranging airlifts of food just to keep dying Biafran babies off television screens. During his campaign in 1968, Richard Nixon had made references to the Biafran famine as genocide, excoriating Johnson for allowing it to happen, but once president, the old policy of “neutrality” was reverted to.

That the British government, leader of the Commonwealth, whose duty it should have been to play the role of mediator, should furnish the most lethal weapons for the massacre of Biafrans, who are themselves citizens of the Commonwealth, surpasses comprehension

By 1969, attempts by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to airlift supplies were frustrated by bombed-out airfields and effectively came to an end when the Nigerian air force shot down one of its relief planes, claiming that arms were being brought in among sacks of Norwegian stockfish and meal. Even the UN refused to get involved in what it saw as an internal conflict, despite the growing evidence of a humanitarian catastrophe of epic proportions. The federal military government of Nigeria would only allow relief aid through if the process were strictly controlled by Lagos via a narrow land corridor policed by its troops, requiring effectual capitulation by the Biafrans. But Stewart stated in the Commons in July 1969, a full year after the policy of starvation had been first indicated by those on the ground: “We must accept that, in the whole history of warfare, any nation which has been in a position to starve its enemy out has done so. As far as I know, this is the first occasion on which a government who were in a position to do so have said, ‘We are willing not to do so provided that there are conditions which ensure that our generosity is not exploited for military ends’.”

Throughout 1968 and 1969, the Red Cross published estimated figures of starvation deaths in the Biafran enclave, rising from 6,000 a day in August 1968 to 10,000 a day by December, and peaking at 12,000 by mid-1969. Based on these ICRC medical surveys, it has been conservatively estimated that anything up to 2 million Biafran men, women and children succumbed to famine during the war. The figure could be significantly higher and doesn’t take into account those killed by the advancing Nigerian federal army and bombing raids by its air force.

Yet the British government continued to maintain supplies of arms to General Gowon’s regime in Lagos and to defend the actions of the Nigerian armed forces in parliament, rejecting any notion that the policy of starvation was remotely genocidal. An international team was sent to the conflict zone, including observers from the UK, not to investigate claims of genocide, but to prove the opposite, a significant distinction given the fact the team never went anywhere near the Biafran enclave and were chaperoned about by Nigerian officers. One member of the team, Major General HT Alexander, told The Spectator in November 1968: “One has to understand, or try to understand, the federal government’s point of view, which is that any form of blockade-breaking is an act of war in that it increases the will of the people to resist.”

Finally, in May 1969, eight months before the end of the war, an independent investigation published under the auspices of the International Committee for the Investigation of Crimes of Genocide, which interviewed over 1,000 people on both sides of the conflict, concluded that evidence of genocide and genocidal intention certainly existed.

Fifty years on, nothing can be sure: black and white photographs, old books and articles, a few real memories. The post-war “settlement” in southeast Nigeria saw Biafrans pretty much marginalised and impoverished by a series of policies intended to punish rather than reconcile. Hardly evidence of genocidal intent on the part of the victors, true, but these policies have gone hand in hand with continuing violence against Igbos, sometimes sporadic, recently intense and on many fronts, often at the hands of either the Nigerian armed forces or government-backed Fulani herdsmen encroaching from the north on Igbo land.

In the last few years, it’s estimated that thousands have died. Nigeria’s current president, Muhammadu Buhari, who as a major in the federal army during the war was responsible for stopping food supplies entering the Biafran enclave via Onitsha, has said recently: “I don’t have any regret, and as such do not owe any apology to them. In fact, if there is a repeat of the civil war again, I will kill more Igbos to save the country.” Many Biafrans have left Nigeria and settled elsewhere in the world, in Britain, the US and Canada, and those who remained, although it is painful, dangerous even to speak of it, have not forgotten the war, the brief existence of a country called Biafra, the land of half a yellow sun, as novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called it.

Twenty years ago, when the documents relating to the Wilson government were made public for the first time, there was a brief resurgence of interest in the Biafran war. No one has ever been prosecuted for the crimes committed then. No crimes have even been acknowledged by the winning side. Successive Nigerian governments have effectively acted with impunity towards Igbo separatists and swept the whole conduct of the war under a political carpet, rejecting any notion of a right to self-determination for the disparate people they rule. Neither has the role of the British government in aiding and abetting the commission of those crimes been scrutinised in any official capacity, nor the acquiescence of the official opposition under Edward Heath. It’s as if millions of people never starved and tens of thousands of civilians were never slaughtered.

In early January 1970, Odumegwu Ojukwu fled to the Ivory Coast. Biafra surrendered on 13 January and the war officially ended on 15 January. The penultimate chapter of Waugh and Cronje’s book ends with an encounter between Waugh and a young Biafran boy. The boy is asked if he thought Biafra could ever win the war. “I think Biafra will win, but it will take a very long time,” he said, and smiled a little ruefully at his poor, emaciated legs – “and I think that many of the people will become like stockfish.”

Stockfish, the thin, dry strips of salted fish sent as part of the famine relief from Scandinavia, was the only protein many starving Biafrans had. The taste for it has lingered on in much Biafran cooking. Its popularity survived a ban imposed by the Nigerian government in the 1980s. People are resilient and the salted fish is once more a staple of markets in Abia and Umuahia, almost an act of collective memory if not actual defiance.

The Biafran people deserve to have their story told, including even the pathetic diet they clung to. What kind of reckoning is possible will depend on Nigeria in the near future. But acknowledgement of the suffering imposed by the Nigerian federal military government and their allies in London, of the humanitarian catastrophe, of the cruelty then and since, is the least the Biafran people should have. If the Nigerian government will not do this, the British are duty-bound to scrutinise the conduct of Wilson’s government during the Biafran war in some official capacity – a government, it’s worth remembering, otherwise dedicated to democratic reform and social equality. It’s a debt owed to the living as well as to the millions who died.

I would like to thank Christopher Gray of Bristol University, whose invaluable research made much of this article possible

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments