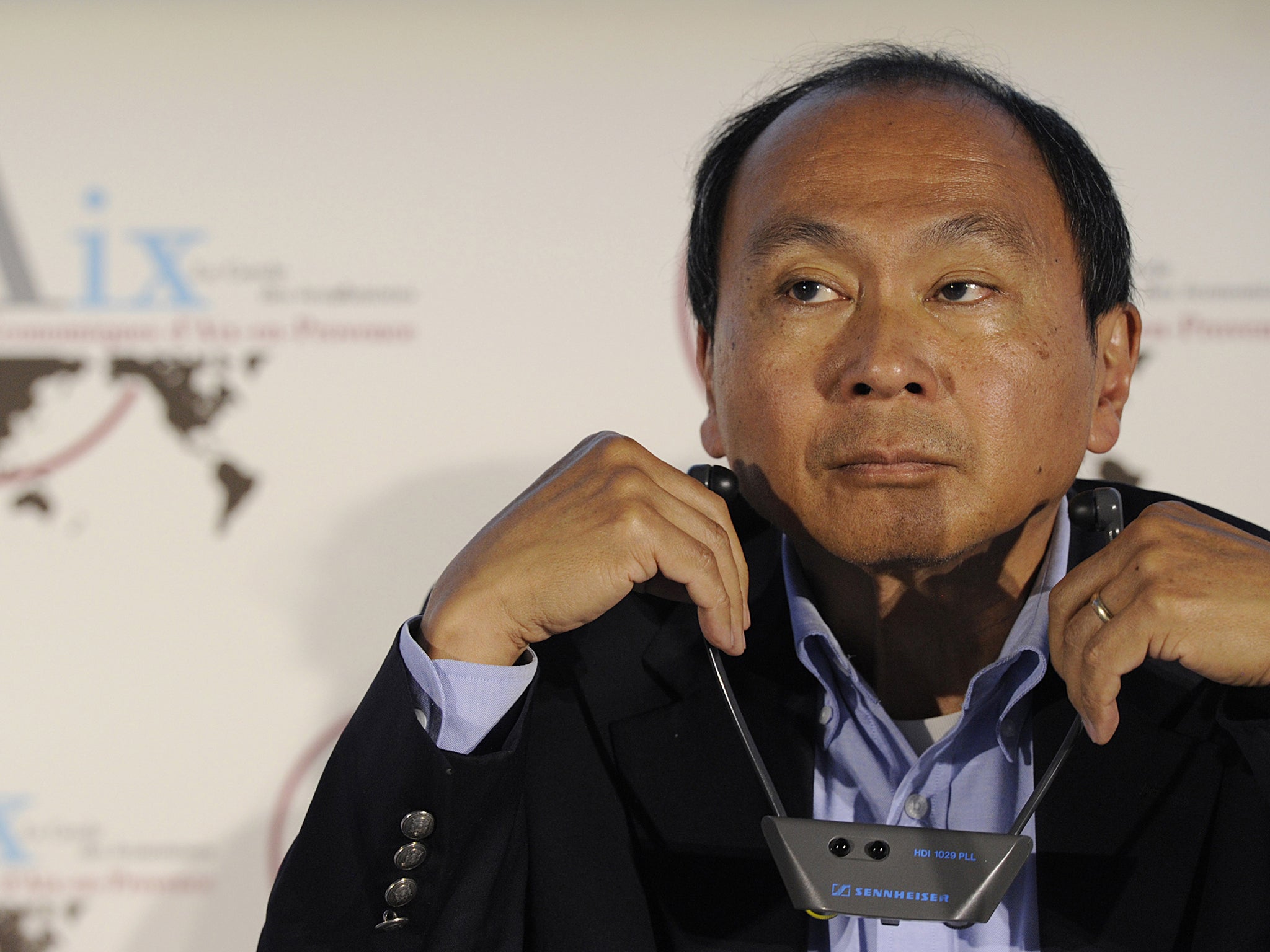

Could the man who declared the end of history hold answers for the future?

Francis Fukuyama spent his life searching for the end, but the biggest question posed by his work is what comes next, writes Arjun Neil Alim

In watching the flow of events over the past decade or so, it is hard to avoid the feeling that something very fundamental has happened in world history.” With this sentence began one of the most epoch-defining, polemic and misunderstood articles of the post-Cold War era. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama published his essay “The End of History?” in the American neoconservative bimonthly magazine The National Interest in the summer of 1989. Thirty-one years later, the debate on modernity and politics rages on.

How is history to end? If history is the evolution of humanity towards a universal state, as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel saw it, then history ends when it reaches a society that satisfies the ideals of Enlightenment philosophy. Since this thought was articulated at the University of Berlin in 1822, political thinkers have striven to interpret Hegel’s historical determinism and apply it to their own era.

Fukuyama’s essay, which he then republished as the book The End of History and the Last Man (1992), was an academic sensation, with scholars from Samuel Huntington to Jacques Derrida writing responses and commentaries. To this day, Fukuyama’s title is used as a byword for the mistaken triumphalism of western liberals after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism in eastern Europe.

Fukuyama’s chef d’oeuvre was self-consciously a “great book”, which claimed to espouse a timeless and universal theory of political evolution. His thesis was as follows: the “victory” of liberal democracy over monarchism in the 19th century, over fascism in the first half of the 20th century and finally over communism in 1989 marked the “endpoint of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”.

In short, his was a Marxist reading of the long run of History, with its endpoint as liberal democracy instead of communism. History, with a capital “H”, referring to the progression of human society towards an “ideal”, a “single, coherent evolutionary process”, rather than the history of events or people, had ended. There was thus nothing radically new that humans could theorise or create in politics.

Yet what made Fukuyama stand out among Cold War theorists was his use of political philosophy to support his ideas. He ostensibly draws on, among others, the idealist philosophy of Hegel, who believed that history advanced “dialectically” towards an endpoint. The story of how Hegelianism reached the foreign policy circles of Washington DC is not a simple one. But given the historical determinism and neoconservative foreign policy thinking in the US that followed the end of the Cold War, it is an important one.

Hegel is best known for his “idealism”, his notion that human actions are preceded by a consciousness, and that in the long run, this consciousness will manifest itself in the physical world. For Fukuyama, this consciousness is the philosophically perfect state of western liberal democracy, exemplified by liberal democratic, internationalist and prosperous Denmark.

Almost as a challenge, Fukuyama admits in his initial article: “I have neither the space nor, frankly, the ability to defend in depth Hegel’s radical idealist perspective.” Fukuyama was educated in Hegelian idealist philosophy throughout his academic career; he studied at the universities of Chicago, Yale, Paris and Harvard. His time in the French capital introduced him to Hegel’s most intriguing emissary in the 20th century, Franco-Russian philosopher and European bureaucrat Alexandre Kojève.

Kojève’s famous debate on philosophy and modernity with German Jewish scholar Leo Strauss, who taught Fukuyama’s professor, Allan Bloom, at Chicago, set the intellectual foreground for Fukuyama’s article. More broadly, Fukuyama serves as a case study on the reception of a strand of political Hegelianism and historical determinism in American policy circles, mostly neoconservative, in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Hegel’s philosophy is a key point of origin for the notion that history would lead to a final state of perfection. This “historicism before the fact” is the essential thesis of Hegel’s work The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807). The book establishes three key Hegelian concepts with respect to history: the dialectic of the master and slave, the Spirit (Geist) and the development of Consciousness (Bewusstsein).

The last is the fact of human development that underpins a Hegelian understanding of history; a directional process that reconciles contradictions to culminate in the realisation of an absolute truth; the ideal state of human freedom through Consciousness.

It is important to note that Hegel does not himself explicitly speak of an “end state”, only a direction. This directionalism is the Geist, or spirit, of history, which Hegel believes can inhabit the great movers of history. One such great man was Napoleon Bonaparte, whom Hegel witnessed after his victory over the Prussians at Jena-Auerstedt in 1806. The philosopher wrote to his friend, Friedrich Niethammer, that he witnessed “the spirit of history on horseback”, as he believed that Napoleon incarnated the progress of the values of Enlightenment and the revelation of the absolute truth, against monarchical tyranny, embodied by Prussia. In his Lectures at Jena, Hegel declared triumphantly: “We find ourselves in an important epoch, in a fermentation, in which Spirit has made a leap forward, has gone beyond its previous concrete form and acquired a new one. The whole mass of ideas and concepts that have been current until now, the very bonds of the world, are dissolved and collapsing into themselves like a vision in a dream.”

Kojève shared this view. He taught a seminar on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit from 1933 to 1939 at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. Although Kojève himself remains relatively unknown outside of Paris’s Left Bank, his lectures were attended by influential intellectuals from European philosophical and political modernism, including Hannah Arendt, Raymond Queneau, Georges Bataille, André Breton, Jacques Lacan, Raymond Aron, Jean Hyppolite, Victor Gourevitch and Éric Weil.

New evidence from Soviet archives suggests Kojève might also have been a Soviet asset during his academic life, which adds to the veneer of mysterious radicalism surrounding his scholarship. His interpretation of Hegelian historicism essentially forms the basis of Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis.

Kojève is notorious for his flippant statement that the empirical end of History was the battle of Jena-Auerstedt, which he says marked the beginning of the universalisation of the Enlightenment against tyranny. Writing in 1958, he glosses over the two world wars and the ongoing Cold War as mere effects of and reactions to the universalisation of what he termed the “universal homogenous state”. He wrote: “What has happened since then has been nothing but an extension in the space of the universal revolutionary force actualised in France by Robespierre-Napoleon.” That end state is one in which humans are free from discrimination based on distinctions of class, gender, status or ethnicity. It is, to use his terminology, “universal and homogenous”.

Kojève believed that Left Hegelianism culminated in the Soviet Union, with its official doctrine of post-nationalism and equality. Meanwhile, the free capitalist United States represented Right Hegelianism

Kojève is clear on one crucial element by the 1940s: the age of “historical men” fighting for the progression of history is over. We are living in the end times. In the world of ideas, the universal truth is discovered. In practice, humans should become free and equal. In a letter to Strauss defending his theory, Kojève explains that the end state is the synthesis of Nietzsche and Hegel’s master and slave dialectic, the “worker’s struggle becomes the struggler’s work” and the age of universal military service, ushered in by Napoleon, makes everyone into a “civil servant”. The dialectic of master and slave culminates with the slave’s emancipation and the master’s loss of his superior status: the state becomes simply one of citizens.

The end state for Kojève represents the fusion of two potential universal homogenous states with Hegelian characteristics. The original two strands of Hegel’s thought from his immediate students, conservative “Right” Hegelianism and critical “Left” or “Young” Hegelianism, are neatly embodied in these penultimate states. Writing in the 1940s, Kojève believed that Left Hegelianism culminated in the Soviet Union, with its official doctrine of post-nationalism and equality. Meanwhile, the free capitalist United States represented Right Hegelianism. It was, hence, a synthesis of socialism and capitalism that would end history. Kojève suggests, remarkably and tongue-in-cheek, in his Introduction to the Reading of Hegel that “it might even be said that, from a certain point of view, the United States has already reached the final stage of Marxist ‘communism’, since all the members of a ‘classless society’ can, for all practical purposes, acquire whatever they please, without having to work for it any more than they are inclined to do.” Yet this synthesis of socialism and liberalism, according to Kojève, would be found principally in the “common-marketisation” of the world. “In the first case it will be spoken about in ‘Russian’, and in the second case – ‘European’,” he predicted, for the vanguard of this common-marketisation was the fledgling European Community project, now known as the European Union.

Marx similarly used the Hegelian dialectic and the notion of directional history to theorise that an enlightened, egalitarian society would arise from the contradictions of inequality stemming from class exploitation and unequal ownership of property

In his recently unearthed letters, Kojève explains that post-historical humans will lose a part of their humanity. Free from ideological conflict or ambition, they would become “non-humans”. He clarifies: “Non-human can mean animal, or better automaton, as well as god.” Automata can attain “satisfaction” through “purposeless activity” like art, sport and sex. They can also rebel against the system, either physically, leading to their exclusion, or philosophically, leading to a life of contemplation. Kojève’s “brave new” end state would be a happy time principally because war and revolution would no longer be conceivable. But even he appeared aware of the irony of man becoming lesser at the moment of his ultimate triumph.

Fukuyama’s “The End of History?” thesis is rooted in previous thought on “endism” and the conclusion of ideological strife in political life. He stated, both at the time and retrospectively, that his thesis was twofold: there was an empirical part, examining the contemporary state of the world, and there was a normative argument, concerning the stability and inevitability of liberal democracy.

Empirically, the basis of Fukuyama’s political and historical thought is rooted in contemporary politics. As Hegel wrote in Elements of the Philosophy of Right: “Philosophy is its own time comprehended in thought.” Although it can plausibly be claimed about almost any period, the summer of 1989 was an auspicious time to publish a great theory about the passing of an epoch. Fukuyama spoke in 2013 about the counterintuitive and optimistic spread of democracy in the 1970s and ‘80s, as in southern Europe (Portugal in 1974 and Spain in 1978) and Latin America. Mary Elise Sarotte writes of how 1989 marked the beginning of the struggle to create a post-Cold War world. Early in the year, the signs of a convergence between long-term structural weaknesses in the Soviet “Empire” and short-term political pressures became apparent. In Moscow, semi-free elections in March and April endorsed Mikhail Gorbachev’s ongoing policies of Perestroika and Glasnost (liberalisation, democratisation and openness) in the Soviet Union and its satellite states. In eastern Europe, national democratic movements in the Baltic states, especially in Estonia, as well as in other parts of the Soviet Union began to gain momentum. In East Germany, citizens voted with their feet, crossing the borders into western Europe in their tens of thousands. In short, the end of the superpower standoff between the liberal democratic west and the state-socialist east was perceived to be imminent.

While Kojève theorised on world politics during a peak of Cold War tensions in the 1950s, Fukuyama was more familiar with the decline of the USSR and the seemingly inevitable victory of his liberal democratic US. His initial lecture on “The End of History?” in February 1989, from which the article in 1989 stemmed, was steeped in a contrarian optimism of the inevitable and imminent victory of the western capitalist system. Nor was Fukuyama merely an observer of this phenomenon. Like Kojève, who worked as a bureaucrat in the European Community planning the Common Market in the 1950s, Fukuyama was deputy director of the State Department’s policy planning staff in 1989. He worked under James Baker, President George Bush Senior’s secretary of state, as they planned for the reunification of Germany, the retreat of the Soviet sphere of influence and the extension of liberal democracy across the world. As in Kojève’s vision of Napoleon incarnating the values of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment in his defeat of the Prussians, Fukuyama saw in the fall of Soviet communism the final important victory of liberalism, and the centrepiece of empirical evidence for the end of History.

The normative aspect of Fukuyama’s argument, grounded in ideas and ahistorical philosophy, is equally remarkable. All his work has followed the same logic. History, as in the progressive evolution of political organisation, is directional and spurred on by modern natural science and technological innovation. These changes lead to uniform social and political changes across the world, making societies as diverse as Rwanda and Japan gradually more politically and economically liberal. Fukuyama resurrects a form of modernisation theory, which holds that economic modernisation exists as an aim for almost all societies regardless of cultural specificities and natural science has homogenising and liberalising tendencies. Key facets include the increasingly free flow of information, higher rates of education and the spread of democratic norms. In his more recent work from 2014, Political Order and Political Decay, he outlines the key institutions that arise to sustain this political and economic liberalism, and lead to open democratic societies. These are namely: a strong executive, accountability and the rule of law.

In tracing economic and social evolution to reach an end state of human evolution, Fukuyama is self-consciously reminiscent of famous Hegelian Karl Marx. He similarly used the Hegelian dialectic and the notion of directional history to theorise that an enlightened, egalitarian society would arise from the contradictions of inequality stemming from class exploitation and unequal ownership of property. Like Fukuyama, Marx understands stages of development for historic humans, which progress and break capitalist structures until the point of a state of “communism”, an end state in which humans have complete freedom over their choices and society regulates production, meaning one could “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner”.

Fukuyama, however, posits two key differences between his historicism and that of Marx, besides the obvious discrepancy in endpoint. According to Fukuyama, Marx limited his analytical tools to purely “materialist” factors and rejected the “autonomous power of ideas” that Fukuyama took from Kojève and Hegel. Fukuyama wrote: “Marx reversed the priority of the real and the ideal completely, relegating the entire realm of consciousness – religion, art, culture, philosophy itself – to a ‘superstructure’ that was determined entirely by the prevailing material mode of production.” Ideas, for Marx, derive their importance from existing power structures. For Hegel and Fukuyama, ideas can exist outside of power relations. The other point on which Fukuyama believes he differs from Marx is on the nature of their universal histories. The latter appears to espouse a “strong” universal history, with inevitable travel between stages, whereas Fukuyama emphasises that his universality is “weak”. That is to say that the progression of history is not necessarily “linear, rigid, or deterministic”, there is merely a “predisposition towards liberal democracy”

Yet, Fukuyama was clear that the end of History was not something to be wholly celebrated. It was a victory of liberalism as an idea. But large parts of the world will remain “historical”, and other parts may lapse back into dictatorship or strife, albeit without a higher cause. He expands on Kojève’s theory of the end state as a time when post-humans become animals leading largely meaningless lives. This notion is a key departure point of Fukuyama from Kojevian beliefs. He writes: “The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post-historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history. I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed. Such nostalgia, in fact, will continue to fuel competition and conflict even in the post-historical world for some time to come.”

This passage, which served as a sombre ending to an otherwise optimistic article, is arguably the most crucial, and most overlooked part of his original work, leading American philosopher Susan Shell to label it a “most pessimistic of optimistic books”. Like Kojève, Fukuyama understands that the end of History will have a profound effect on humanity and human nature. However, while Kojève believed that humans would merely “sink down into a brutish contentment with material comforts, rather like dogs lying around in the afternoon sun”, the latter predicted that a life of rational consumption, what Fukuyama calls “masterless slavery” would not satisfy the ambitions and egoism of many humans.

In the 21st century, Fukuyama’s thesis has been subject to significant strain. Triumphalist his original article was not

The influence of Nietzsche on this proposal cannot be overstated, his shadow hangs over the master-slave dynamic of Kojève and discussions of morality, from On the Genealogy of Morality: A Polemic. His notion of der letzte mensch (the last man) from Thus Spoke Zarathustra is key in discussions of the post-historical man in Fukuyama. Nietzsche’s last man is illustrated by a group of “wretched” humans who lack ambition, individuality and creativity, who are content to seek only comfort and security, in direct contrast to the Übermensch (Superman), an imaginary superior being who rejects this so-called slave morality. Fukuyama accepts elements of this Nietzschean critique of “rational modernity” and the tragedy of post-human life, most notably by incorporating “And The Last Man” into the title of his 1992 book.

In the 21st century, Fukuyama’s thesis has been subject to significant strain. Triumphalist his original article was not. He warned of the risks of Islamic terrorism, of identity politics, of ongoing conflicts both in the historic world (the global south), such as the Indo-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir, and the post-historic world, for example the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In response to critiques and ongoing structural shifts, Fukuyama has clarified two elements of his thesis to date. The first is a re-evaluation of economic liberalism, in response to widening wealth and income inequality in the western world. Fukuyama has spoken out against unregulated capitalism and called for “more socialism”, in that regulation and redistribution programmes are necessary to sustain a liberal democratic system.

Fukuyama has also condemned neoconservatives, who used his ideas, along with those of Strauss, to justify the use of force to spread democracy around the world. In his article “After Neoconservatism” in 2006, he compares his “kind of Marxist” original thesis of a long process of evolution towards liberal democracy to those on the right in America who were Leninists in their artificial and forced application of his thesis to pre-democratic states such as Iraq. Fukuyama also famously warned that his concept thymos, the desire for recognition, can be superseded by a megalothymia, the desire to be recognised as superior, as in Nietzsche’s Superman. He warned in his 1992 book that ambitious and egoistic individuals, exemplified by “a [property] developer like Donald Trump”, could be unsatisfied by universal and equal recognition and lead to a “resurgence” of History. Fukuyama did not predict the events and structural factors that led to the latter’s surprise election in 2016, but to believe that any single event has “disproven” the end of history, as a long process of evolution, would be based on a simplified understanding of Fukuyama’s thesis.

“The End of History?” is both the product of centuries of theorising on modernity, history and philosophy as well as the culmination of an extraordinary academic career. Yet, Fukuyama’s piece was equally seminal as it marked the opening shot of the frenetic debates over postmodernism. By internationalising and popularising the debate over the end of History, the question of what comes next was inevitably posed. From Kojève, to Strauss and Bloom, the answer is not good. To accept an end to History is, in many ways, to embrace a “crisis of modernity” as Strauss predicted. Fukuyama theorised that men were never as free or as human as when they were fighting for their rights.

Kojève’s idea of ‘philosophical contemplation’ at the end of History has, for some, led to the threat of postmodernism undermining the central tenets of the west

Kojève’s idea of “philosophical contemplation” at the end of History has, for some, led to the threat of postmodernism undermining the central tenets of the west: enlightenment philosophy, equal rights, representative democracy. Bloom warned of precisely this in his bestselling book The Closing of the American Mind. Fukuyama echoed him in suggesting that “modern education stimulates a certain tendency towards relativism, the doctrine that all horizons and value systems are relative to their time and place, and that none are true, but reflect the prejudices or interests of those who advance them”.

Professor of history at Oxford Brookes, Roger Griffin’s book Modernity and Fascism is but one text that explains how fascism might offer a “sense of a beginning” that will become ever more attractive in an increasingly morally relativist west. One contemporary conservative thinker blames postmodernism for many of the west’s social problems, and amusingly accuses the literature department at Yale for importing nihilistic French poststructuralism. Similarly, one could trace the origins of this historical determinism from Hegel’s University of Berlin, through Kojève’s Paris to the Classics Department of Cornell and the Political Science Department of Chicago.

Fukuyama’s thesis also acts as an expedient case study on the reception of Hegelian historicism and the notion of the end of History in the modern west. Fukuyama’s influence among the network of American neoconservatives in academia and in the Bush and Reagan administrations has also been revealed. Yet Fukuyama himself has stressed that his thesis had no foreign policy implications, and actively condemned those neoconservatives who interpreted his thesis as an interventionist doctrine, notably in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the belief that one lives under the philosophically best possible system certainly has policy implications. Robert Cooper, a former senior foreign policy advisor to Tony Blair and European Union civil servant, told The Guardian in 2002: “I’m a fan. The world Fukuyama described is an accurate description of the world we operate in.” The current French president, Emmanuel Macron, a self-confessed Hegelian, has spoken at length on the notion of “grand political narratives” and retains a Kojève-esque faith in the EU. Europhiles in Britain might bemoan the decision of voters to drag their country kicking and screaming back into history.

In the east, where more attention is paid to Strauss’s neoconservatism, a new end of History is appearing in the managerial authoritarian states of China, Vietnam and Singapore. Fukuyama himself acknowledged the possibility that a stable and prosperous China could offer “an alternative modernity”. Two other ends of History, less optimistic and more nihilistic, also pose themselves. The first is the end of humanity through the holistic destruction of nature and the biosphere. The second is the end of the Homo sapiens species, through modern science and genetic engineering, as thinkers like Yuval Noah Harari predict. Rather than a definitive end, modernity has revealed itself to be a continuous debate, between optimists, pessimists, civilisationists, historicists and relativists.

One question remains. What led Fukuyama to the ultimate search for the end? Fukuyama was born in 1952 to a middle-class academic family and grew up on New York’s Lower East Side. His father was a congregational minister and professor of religion, giving Fukuyama an early experience of both academia and teleological, eschatological theories of history. The shadow of Strauss hung over Fukuyama’s undergraduate education; he majored in classics (Latin, Greek and the culture of both civilisations) at the University of Cornell. His housemaster was Bloom, with whom Fukuyama recounted many late nights discussing philosophy and “Great Books” and “Great Ideas” – a genre for which Bloom was passionate.

After his undergraduate degree, Fukuyama studied comparative literature at Yale and the University of Paris. Comparative literature in the 1970s was to be a critical poststructural environment, where students were encouraged to question and criticise key texts in western literature and culture. At Yale, Fukuyama studied with deconstructionist Paul de Man. In Paris, he studied under Roland Barthes and Derrida, who sat in on Kojève’s lectures on Hegel in the 1930s, and who went on to become seminal scholars in the French poststructuralist school. This school of thought, epitomised by Derrida, questions the origin, presentation and possibility objective facts (known as “structures”).

Yet Fukuyama’s self-described “intellectual side journey” came to an end after six months in Paris after he grew disillusioned with the negativistic and abstract nature of poststructuralism. He told The New York Times’s James Atlas: “I was turned off by their nihilistic idea of what literature was all about, it had nothing to do with the world. I developed such an aversion to that whole over-intellectual approach that I turned to nuclear weapons instead.” Similar to Kojève’s insistence that philosophy has no value if not applied to its own time, Fukuyama’s academic career led him to pursue more practical subjects.

At Harvard, he pursued a PhD in Soviet foreign policy in the Middle East in the context of the Cold War. In 1981, he left the neoconservative Rand Corporation, a public policy thinktank, to work for Paul Wolfowitz, director of policy planning in the Reagan administration and another former student of Bloom. Fukuyama spent the rest of the 1980s working between public policy, foreign policy and the Bush administration. He always kept one foot in policy and one in academia, even during the heavy years where Fukuyama was involved in the secretary of state’s negotiations over Palestinian autonomy and later German reunification.

As such, in 1989 the John M Olin Centre for Inquiry into the Theory and Practice of Democracy at the University of Chicago presented a lecture series on the Cold War and the wider state of global order titled “The Decline of the West?” In a quirk of history, and a testament to the value of networking, the John Olin Centre was headed by none other than Bloom. They invited a public policy researcher, whom Bloom’s co-host Nathan Tarcov described as having an “interesting and unusual intellectual trajectory … interested and knowledgeable about literary and aesthetic matters”. The functionary accepted, and his lecture title opposed the wider defeatist tone of the conference. It posed a simple question with a Great Idea: “Are We Approaching The End of History?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments