The origin of clothes: from pure function to fashion must-haves

It started off as purely functional – to protect and keep us warm – but it became an object of desire and a symbol of status. Andy Martin on the evolution of clothing

It only took us 1 million years to work out how to make clothes. That’s the time between when we began to shed our body hair and become naked apes and when we first started to wrap up warm in animal skins. Archaeologically, the evidence is fairly clear. Not, of course, that you are going to find too many remnants of Paleolithic party dresses and fur coats. We have a 3,000 year-old pair of woollen trousers, with woven leg decorations (worn by the nomadic horsemen of Central Asia). The oldest rags we now possess – a few twisted flax threads – date from around 34,000 years ago.

But you can find older evidence of the equipment that was used to produce clothing. Artefacts such as awls and needles, of the kind that would have been needed to sew animal skins into wearable garments, have been discovered dating back around 50,000 years (notably in the Denisova cave in Siberia). Even allowing for a generous margin and for cruder scraping implements, proto-clothing goes back only to the origin of homo sapiens, one or 200,000 years ago (the origin of the body louse, which lives in clothing, may go back as far as 170,000 years ago). So it is clear that for at least a million years our hominid precursors were running around stark naked.

Both the climate (in Africa) and the running (either away from or after an animal) ensured we stayed fairly warm. In fact the concept of nakedness is strictly anachronistic: how could we even know we were naked until we had the option of not being naked? It wasn’t until we invented clothing that we realised that we had been naked before. The “nude” – ie someone devoid of clothing – was born. Finally, around the same time as cave paintings, the very possibility of pornography was established. The Bible has it back to front: the use of fig leaves is what causes us to feel naked when fig-free.

The fetching rough-hewn animal-hide bikini as sported by Raquel Welch in the movie One Million Years BC (“This is the way it was” ran the slogan) will have been greatly sought after, since demand quickly outstripped supply. Clothing protected us from the increasing wind chill as we ventured out of Africa and ultimately up into Siberia and Alaska and we were hit by the Ice Age(s). We developed multiple layers to prevent frostbite and thereby acquired underwear. But what was functional was also fun and therefore coveted. Clothing became an object of desire. It could be bartered and it could be stolen, although the original wearer would almost certainly have to be killed before you could start wearing it.

But clothing also changed the way we think. Our brains absorbed the notion of the cover-up, turning us into the scheming but neurotic wrecks we are today. Ian Gilligan, a prehistorian at the University of Sydney, and the author of Climate, Clothing and Agriculture in Prehistory, argues that the invention of this early “technology” had many repercussions for the evolution of humanity, including notably the rise of agriculture. It wasn’t all about baking and brewing.

Clothing became an object of desire. It could be bartered and it could be stolen, although the original wearer would almost certainly have to be killed before you could start wearing it

Gilligan points to an earlier instance of global warming 12,000 years ago in the transition between the Pleistocene and the Holocene. The climate became warmer and wetter. We couldn’t just rip all our kit off by this stage of the game. We would have been forced to switch from animal hides to textiles to cool down. So cotton naturally became a huge commodity. As, in the tropics, did the fibre of the wild banana. We were growing grain too, but we were mainly growing clothing material. And herding sheep and goats and llamas and alpacas for the sake of harvesting their wool.

Gilligan says: “It is hard to see why prehistoric hunter-gatherers would ever start with agriculture solely to obtain food, and maybe they never did.” We could have gone on finding food as hunter-gatherers, but the need for a decent set of clothes to put on, ones that weren’t as sticky as leather and fur, required us to put down roots and become sedentary and civilised. And start weaving.

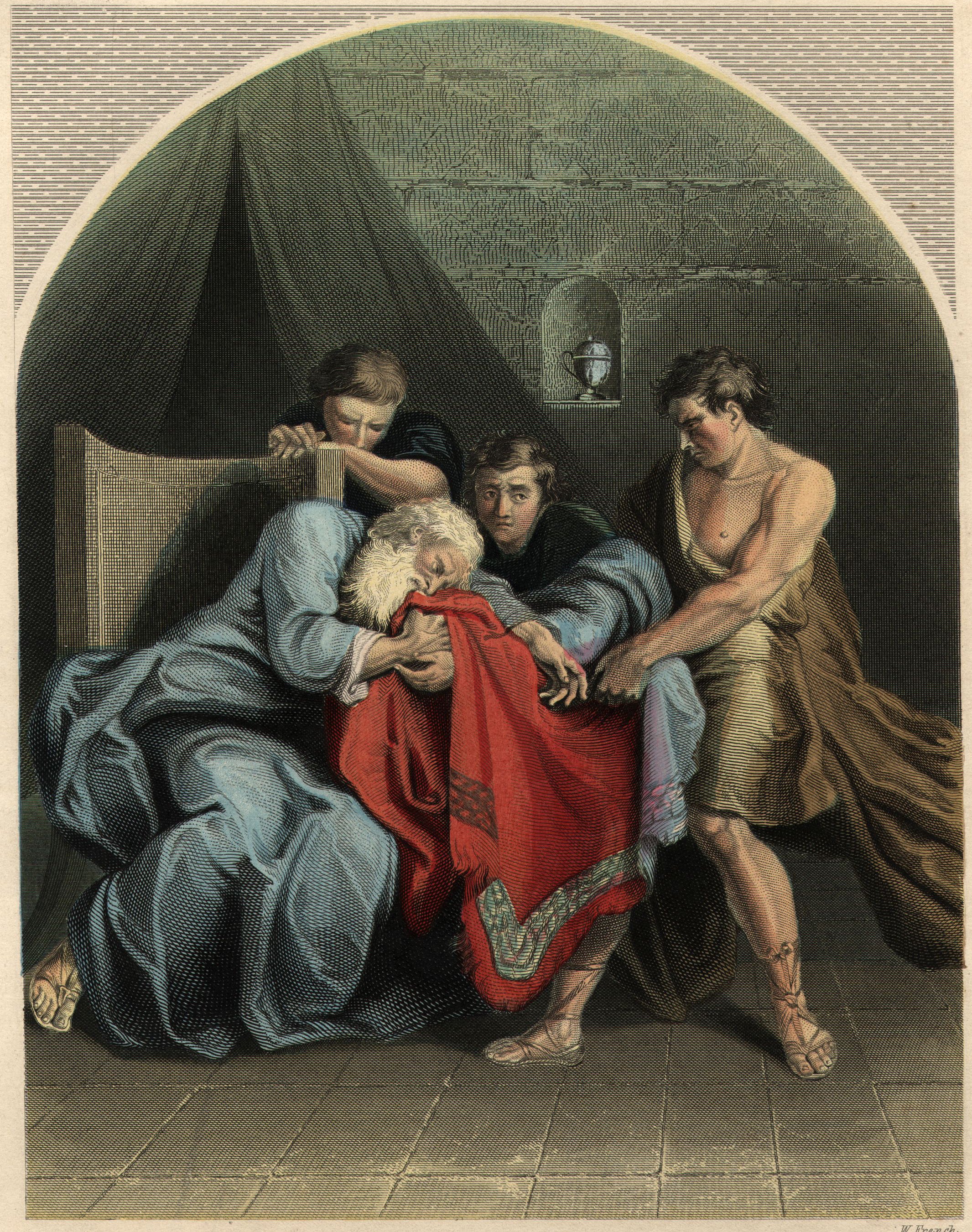

What people wear gets into the Bible and the Quran. Joseph’s “amazing technicolour dreamcoat”, or “coat of many colours”, shows how certain types of clothing were already a mark of distinction and could easily arouse envy and violence. And the tools for making clothes make an appearance too. “So it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God”. Silk is a signifier of earthly wealth if not wisdom. Conversely, to walk without sandals is a sign of poverty. Sinners deserve only sackcloth and ashes. But the right kind of clothing was invested with the sacred. Priests would wear elaborate vestments that denoted greater proximity to God.

In other words, clothing quickly became detached from pure function and entered the realm of the symbolic. As does, conversely, going without clothes altogether, or only wearing some minimal covering, which becomes equated with primitivism and sexuality, and therefore to be prohibited or regulated. No wonder the Naked Rambler kept getting arrested, particularly in Scotland. But our evolving sense of shame is not only to do with the ultimate nightmare of walking down the high street and discovering you forgot to put any clothes on, but also with wardrobe malfunctions generally.

By the same token our clothing has shaped the way we think. Ever since figleaves and loincloths, we have acquired “enclothed cognition”. Fast forward to the present, passing through the invention of the spinning jenny, the industrialisation of clothing, and the rise of Boohoo, and we are now the inheritors of this primal obsessing over what to wear – or not.

Shakaila Forbes-Bell is a psychologist of fashion who might be able to save us from the Imelda Marcos syndrome. She used to wear a diamante necklace that spelt out the words, “Don’t worry, be happy”. She still bitterly regrets losing it. “That necklace was such a conversation starter. It opened doors for me.” So many T-shirts now carry actual statements or slogans or wisecracks, but all clothes send out a message. The lyric suggests that clothes are like a love song – a romance. They externalise the fantasies we have about ourselves.

Forbes-Bell studied the psychology of fashion at University College, London, and took an MA at the London College of Fashion. Her final year project was on “clothing and race”, zeroing in on how a perception of Trayvon Martin’s hoodie fed into his brutal killing. She was into both fashion and psychology and has now found a way to do both with her website, Fashion is Psychology, which hosts blogs about clothing and applies complex academic theories to our quotidian lives. She also works with companies like Next and Sainsbury’s to identify consumer behaviour and motivation.

Everything you wear stands for something else. It never is what it is. Even if you’re going around in droopy old cardigans with holes in the elbows, or you buy your boots at the hardware store, that’s still a style choice. There is no escaping the imperatives of fashion. The only solution – if you can afford it – is to give yourself options. “I hate the idea of having a signature style,” says Forbes-Bell. “One day I can be a Caribbean carnival queen – another day I can be a scholar or a business woman – or boho chic.” The two photographs included here (above) make the point vividly. Pre-pandemic, she went every year to the Trinidad carnival. “Clothes are a tool. You should use them to celebrate the body. Rather than hiding it.” Her carnival outfit is known as a “Masquerader” costume, designed by Rawle Permanand, and she was part of the “Yuma” band.

All clothes advertise our affiliations. They are inescapably tribal. Back in the day it was mods vs rockers. Then it was punk. Or possibly goth. Forbes-Bell is trying to resist some of our more divisive taxonomies. “In 2016 a Vogue editor came out and said if I put a black model on the cover it doesn’t sell. I wanted to disprove that. It was doing a lot of psychological damage.” She published a paper in the Journal of Market Research that demonstrated that black people were willing to pay more for a perfume modelled by a black person. “The black and brown pound is incredibly strong. We are seeing increased representation, but black fashion models are still proportionately under-represented.”

But the clothes we wear can also affect how we feel about ourselves. And they can boost your mood (or the exact opposite). Forbes-Bell cites one experiment in which people were given Superman T-shirts to wear. They felt stronger than the control group who did not have Superman kit. She ascribes the result to “heuristics” – a set of associations we carry around in our heads, largely derived from the culture at large. Wearing a white lab coat actually helps you be more scientific, a suit makes you more strategic.

But pure physical comfort is also a top priority for her. “If you wear clothes that don’t fit, it screams failure. Wear what fits you now, your current shape.” When I speak to her she is wearing a loose white shirt and jogging bottoms. “Comfortable clothes allow you to process better,” she says. “You need to be not distracted by uncomfortable items. Comfort aids cognition.”

Quite what effect the Elvis jumpsuit had on his cognition is unknown. I do know that it is the single piece of kit that all Elvis imitators zero in on. It also happens to be, to my way of thinking, one of the most spectacularly absurd garments ever created, post-figleaf. And it demonstrates that there is no item of clothing, no matter how lame some may consider it, that does not have its champions – in this case, Forbes-Bell herself. “Outlandish and bold costumes were used by Elvis to step into the role of ‘King of Rock’. Costume designers use outfits to help performers embody their characters. It's more than a way to get noticed, it's a way to embody the traits you associate with that outfit. No one will look at that jumpsuit and think ‘safe’, they think ‘bold’, ‘daring’, ‘thrilling’ which correlates with the designer Bill Belew being inspired by the Napoleonic era.”

Even if you are not a nudist, you have to admit that there is something liberating about getting all your kit off

Every wardrobe is a whole ethnography, it contains a culture. And it is a hanging space for nostalgia. All those old items you can’t bear to get rid of. Forbes-Bell still has tons of party dresses suitable for the 18-year old Shakaila. “I couldn’t part with them, they are what I used to be. Your clothes are like a memory box. They take you back in time.” Looking into my own wardrobe, I see that, if it is dug up again in a few thousand years time, there is a high probability that I might be mistaken for someone called Paul Smith. I’m probably guilty of fetishising a label.

But are we simply buying too many clothes? Clothes have almost certainly assisted not only in making humans warmer, but in making the whole planet just a little bit warmer, and therefore more uncomfortable for humans. Textile production now accounts for 10 per cent of the world’s carbon emissions, not to mention all the landfill and water usage. In 2020, it is estimated that 100 billion new garments were made.

We are in danger of drowning in excess. Of being clobbered by our own clothing. The person who owns the most clothes of anyone I know is called Elsa. She has a loft in Stockholm stacked from floor to ceiling (and it is a very high ceiling at that) with thousands of items of clothing. Hats galore: shoes, boots, ties, dinner jackets, waistcoats, ball dresses, regalia of all kinds. Both men’s and women’s.

She has a good reason though, what with being a costumier providing clothes for theatre and film. When she lands at an airport, she has to wait while a dozen or more trunks of clothes appear on the conveyor belt. She has to pay a fortune in supplementary baggage charges. “I have so much shit,” as she neatly puts it. Maybe it is not surprising that she fantasises about being more like the fictional figure of Jack Reacher, who only owns the clothes he happens to be wearing at the time (and chucks them when they get covered in someone else’s blood) and carries only a folding toothbrush in his pocket.

It is inevitable that with the new era of global warming, wearing less is going to become the norm. Even if you are not a nudist, you have to admit that there is something liberating about getting all your kit off, especially to go skinny-dipping in the summer. Even the professionals who make a living out of clothes, yearn to go naked again, if only for a while.

Maybe at heart we all want to revert to our million-year-long golden age, when we didn’t need to worry too much about what we were wearing. “Don’t worry, be happy” is still good advice.

Andy Martin is the author of Surf, Sweat and Tears: the Epic Life and Mysterious Death of Edward George William Omar Deerhurst (OR Books).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks